The final act and the restoration

For much of the Tokugawa Shogunate’s rule, Japan was governed through a strictly enforced feudal system with a clearly defined social order. Under the sakoku policy, foreign influence was tightly controlled to strengthen the government's position. However, by the 19th century, internal and external pressures began to weaken this system, leading to an era of instability and decline known as the Bakumatsu (幕末 – The Final Act).

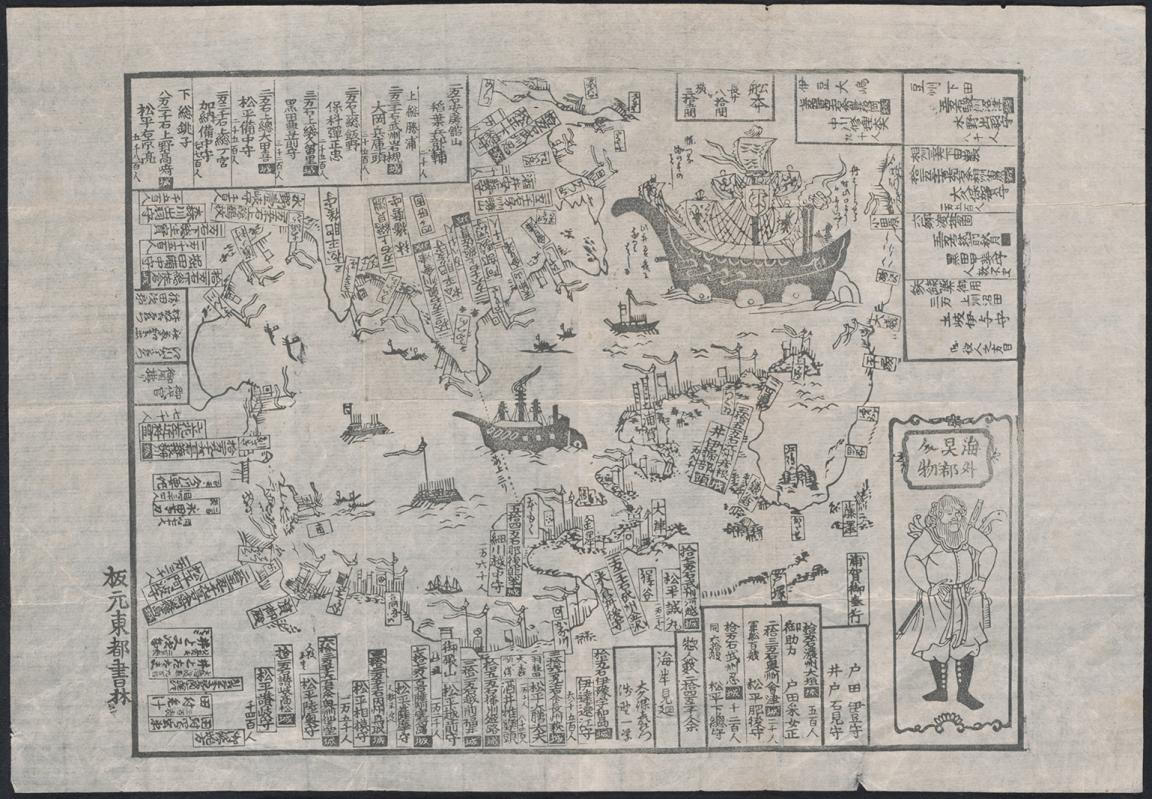

Map of American ships arriving at Uraga, 1853, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-416708988

Map of American ships arriving at Uraga, 1853, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-416708988

Osaka rebellion and rising unrest

In 1833 and 1836, poor harvests in the Kansai district led to severe food shortages, driving up prices and taxes. The people, unaccustomed to such hardships, grew frustrated with the government’s inability to respond. In 1837, Oshiro Heihachiro, a scholar critical of the Tokugawa government, directed public anger towards the bakufu by organizing attacks on tax offices and food storehouses. Though the rebellion was quickly suppressed, the underlying discontent with the government remained.

The black ships and the opening of Japan

Japan’s isolation was further challenged when Western nations, particularly the United States, pressured the country to open its borders. In 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry arrived with four warships (the "Black Ships") and demanded that Japan open trade with the United States. Despite initial resistance, the Japanese eventually conceded, signing the Convention of Kanagawa in 1854, which established diplomatic relations between Japan and the US. The opening of Japan (開国 – keikoku) exposed the Shogunate’s vulnerabilities and further fuelled internal divisions.

Activity 1: Debating modernisation

Evaluate the pros and cons of opening Japan to Western influence.

- What were the main reasons for and against opening Japan to the West?

- How might modernisation affect Japan’s culture and traditions?

Edo-wan okatame no zu, Tōto Shorin, late 19th century, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-151489510

Edo-wan okatame no zu, Tōto Shorin, late 19th century, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-151489510

Tensions between factions

The opening of Japan led to the rise of opposing political factions. Pro-western reformers advocated for modernisation, sending samurai to study in the US, while anti-western factions rallied under the slogan Sonnō Jōi (尊皇攘夷 – Revere the Emperor, Expel the Western Barbarians). Tensions escalated when the anti-western movement received Imperial support in 1863 with an edict ordering the expulsion of foreigners. Conflict over these divisions led to the assassination of pro-western officials, such as Ii Naosuke, and increased pressure on the Shogunate.

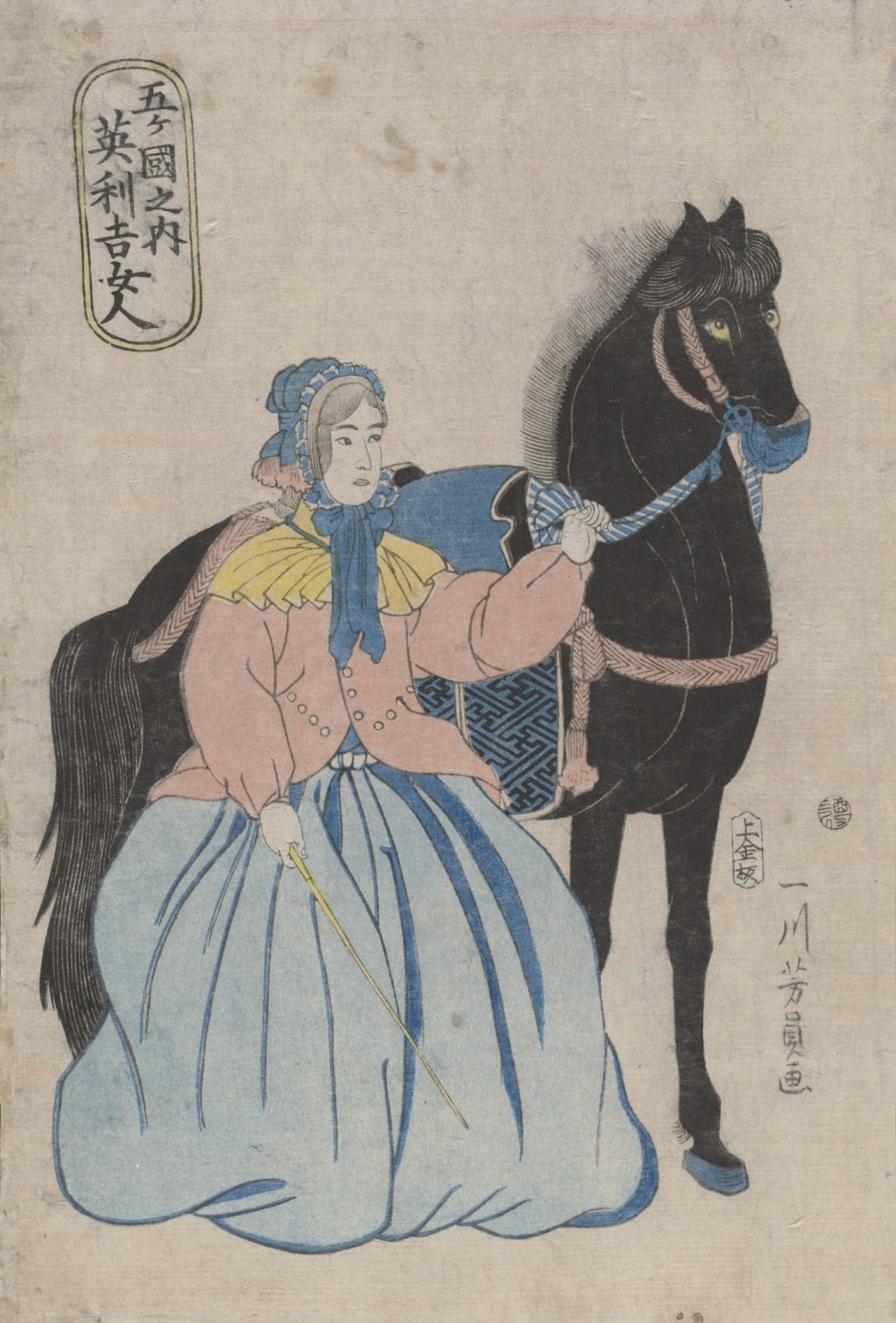

Yoshikazu Utagawa & 歌川芳員, Gokakoku no uchi Igirisu nyonin, 1860, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-151442463

Yoshikazu Utagawa & 歌川芳員, Gokakoku no uchi Igirisu nyonin, 1860, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-151442463

The Boshin war and the fall of the Shogunate

After the death of Tokugawa Iemochi, his successor, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, sought a compromise by ceding power to the Imperial Court. However, opposition to the Shogunate persisted, culminating in the Boshin War (1868–1869). Loyalist forces, especially from the powerful Satsuma, Choshu, and Tosa domains, supported the Emperor and sought to dismantle the Shogunate entirely. The decisive Battle of Toba–Fushimi in 1868 marked a turning point, leading to Yoshinobu’s surrender and the restoration of Imperial power.

Activity 2: A persuasive speech to the Emperor

Imagine you are a samurai tasked with persuading Emperor Meiji to adopt Western technology.

- Choose a piece of Western technology or social reform you believe will benefit Japan.

- Write a speech for the Emperor, outlining why adopting this change is essential for Japan’s future success.

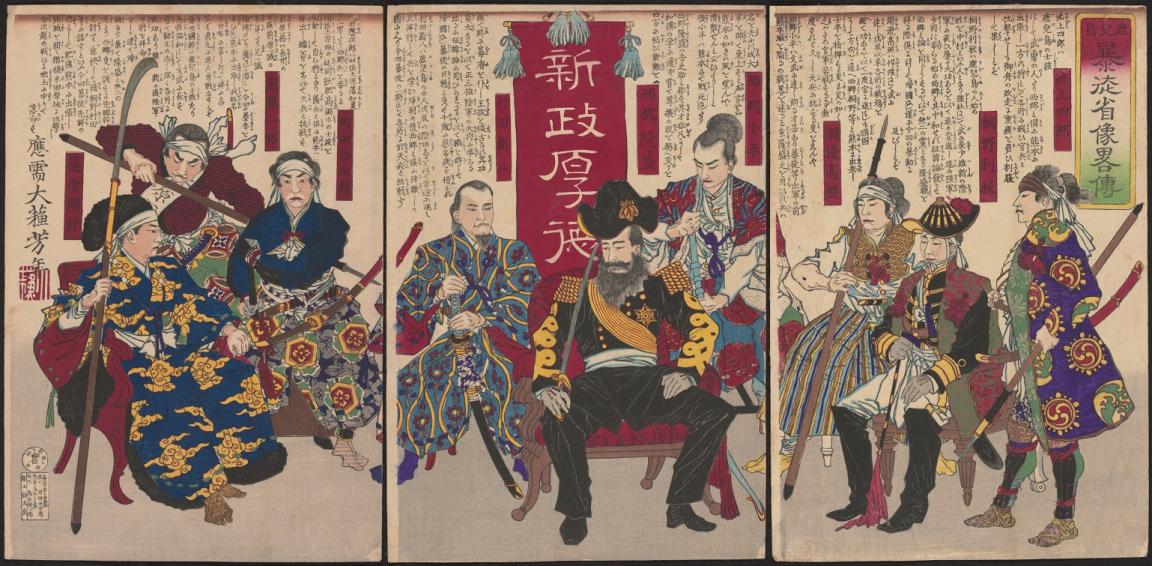

Yoshitoshi Taiso & 大蘇芳年, Kagoshima bōto shōzō ryakuden Morimoto Junzaburō, Tōkyō, 1877, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-152241305

Yoshitoshi Taiso & 大蘇芳年, Kagoshima bōto shōzō ryakuden Morimoto Junzaburō, Tōkyō, 1877, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-152241305

The Meiji restoration and Japan’s path to modernisation

With the Shogunate’s defeat, the Meiji Restoration began. The Emperor regained full power for the first time in centuries, initiating sweeping reforms. Under the slogan Fukoku Kyōhei (富国強兵 – Enrich the Country, Strengthen the Military), Japan pursued rapid industrialisation, establishing railroads, modern communication systems, and national conscription. The government adopted Western technologies and social practices to enhance the country’s industrial and military strength. By the early 20th century, Japan emerged as a modern, militarised nation, marked by victories in the Sino-Japanese War and Russo-Japanese War.

The Bakumatsu and Meiji Restoration represent pivotal shifts in Japanese history, transitioning the country from feudal isolation to a centralised, modern state. By embracing industrialisation and selective Western influences, Japan transformed itself into a competitive global power, setting the stage for its influential role in the 20th century.