Book Launch: Clever Men by Professor Martin Thomas

What really happened when Charles Mountford led a quarrelsome team of Australian and American scientists to explore traditional Aboriginal life in Arnhem Land in 1948?

Here was I with the status of little more than a telephone mechanic, taking out the biggest scientific expedition in history.

In this way the legendary Charles Mountford immodestly described his biggest assignment: to lead an expedition of American and Australian scientists to Arnhem Land in northern Australia, investigating traditional Aboriginal life and the tropical environment. Backed by National Geographic, the Smithsonian Institution, and the Australian government, it was also a display of the friendship between Australia and the US.

But the adventure turned out to be anything but friendly. In this compelling account, award-winning historian Martin Thomas tells how they set out with fanfare in 1948 and how quickly the expedition turned toxic. Thomas uncovers the secrets, scandals, and unlikely achievements. He also reveals how Indigenous communities, including the elders known as 'clever men', dealt with the intrusion of these foreign 'experts'.

Drawing on years of collaborative research with Arnhem Land communities, Clever Men is a poignant portrayal of colliding worlds. In this encounter between scientific hubris and the world's oldest surviving cultures, Thomas finds a story of global significance and profound long-term impacts.

Event video

Book Launch: Clever Men by Professor Martin Thomas

Rebecca Bateman: Oh, we got the lights. Yuma everybody. Good evening and welcome to the National Library. My name is Rebecca Bateman and I'm the Director of Indigenous Engagement here at the National Library. And I'm really, really pleased that we, and thrilled that we are joined here this evening by a very special friend of the Library, Aunty Violet Sheridan, who has come along to welcome us to country. Thank you.

Aunty Violet Sheridan: Thank you, Beck. It is my pleasure to be here in this cold night, but I've spent the day with teenagers at a youth for youth NAIDOC day. And can you imagine I had to stand there and listen to rap music. It was so interesting. It was. But it was a fabulous day even though it was freezing and we had the rappers, but we had some good singers as well. So welcome. I'm looking, really interested in waiting to hear about this book because they was my people, not my people, but other [unclear] across the country. It was taken from the lands and taken to be studied and we a couple of years ago had one remains returned to us and buried. So it'll be interesting to see.

And Martin said the Americans, the Australians, and the English, is where, the Americans, Americans, well it wasn't the Australians really was it? It was the pommies and the Americans that removed a lot of our ancestors. But I always worry about are we getting our people back? But Martin reassures me that the people, the professors that did take the people and the remains that they all numbered. So I'll take that on an assurance that we have got the right people returned to the right traditional owners.

So welcome to the land of the Ngunnawal people. And it is my pleasure to be here and really interested in a lot of this book and what comes out of the stories. So it'll be interesting. So I stand in this place where once my ancestors lived, practised culture raised their families. I am a proud Ngunnawal woman as I carry my ancestors in spirit, walking into the future, teaching the next generations about the oldest culture in the world, my culture, the Ngunnawal Aboriginal culture. I'd like to pay my respects to my elders past, present and emerging and extend that respect to First Nations people here this evening. But I'd also like to acknowledge the non-indigenous people here this evening as well as the many cultures we have. Because Canberra's like a big melting pot. We have so many different cultures that we all can learn off.

So in keeping in the general spirit of friendship and reconciliation, it gives me great pleasure once again to welcome you to the land of the Ngunnawal people. And on behalf of my family and the other Ngunnawal families, I say welcome. This is my mother's land. My mother is a Ngunnawal woman. My father is a Wiradjuri man, but I follow my matriarch's line, so thanks so much Martin. So I'm interested, I'm sure our audience are interested because I'm always into different things and politics is my number one. Thank you all so much. Thank you.

Rebecca Bateman: Thank you so much Aunty. Definitely a chilly one out there today and tonight on a Ngunnawal country. I'm a visitor to country here. I'm a Weilwan and Gamilaroi woman, but I'm always so grateful to be here on this beautiful country and to be every time that I hear only Violet speaking and others, I'm reminded of how special this country is and how lucky we are to be here.

I also always like to extend my respects obviously to the Ngunnawal people elders past and present, but also to extend my respects to all of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples whose stories and knowledges and cultures and histories the National Library is a custodian of. As a national institute, we have a very large remit and we hold lots and lots of very important documentation. And so my respects the role of myself and my team is to make sure that those materials are cared for, connected back to community, and it's something that we take very seriously.

Before I continue, I've been asked to remind you all too if you could just check to see that your phone is on silent, that would be really wonderful. I just have to remind myself to do the same thing and a very warm welcome to the National Library.

Tonight is a really important and exciting night and I'm really pleased to welcome Professor Martin Thomas and Professor Jon Altman who will be discussing Professor Martin's new book, 'Clever Men'.

It's an event that's came after some lengthy consideration by the Library. 'Clever Men', as many of you know, is the story of what was called a scientific expedition to Arnhem Land in 1948. For the scientists and researchers involved such an exposition is largely, I'm imagining, an undertaking of learning, uncovering a better understanding the world that we live in. All very worthy pursuits. For the indigenous people, I'm guessing who welcomed these people to their country I'm guessing it was a very, very different experience that they saw through a very different lens.

I was just reflecting today on what must be like to have been somebody living in community and to have suddenly all these new people arrive, to be asked to explain your culture and share your language and your traditional knowledges. It must have been unsettling to say the very least. And of course we know that there were less fortunate things that occurred like the recording of secret and sacred practises that perhaps weren't meant to be shared. And no doubt that caused distress as well to the affected communities.

And of course, as Aunty Violet alluded to as well, Martin's book addresses the practises of the time of removing ancestral remains to be studied. I too, my community out in western New South Wales has also had an experience of the repatriation of some of our ancestors. And it's a really such an important thing to bring our old people back home. And every time I go out there, I know where they are and I can pay my respects.

Having said that, we have an Indigenous Cultural Intellectual Property Protocol here at the Library, an ICIP Protocol, which along with our First Nations pillar that's in our corporate plan, really clearly articulates our commitment to ensuring the centrality of indigenous voices in the telling of indigenous stories. And this one is very much an indigenous story.

So when Professor Thomas first contacted us, we were really keen to support the launch of this very important book. But we wanted to do it in a way that aligned with our protocol and with our commitment to centering indigenous voices. Thankfully, after chatting with Martin, we were quickly assured, very quickly reassured, that the Yolngu communities, which were not only okay with this, but very central in the telling of this story that was music to our ears. In fact, Martin's words in the prologue of this book reflect the library's position and what we want it to achieve tonight very well. And I quote, to determine the effect of an expedition on the people it encountered it is to go to those communities and find out. It is amazing how many historians don't go to the places they're studying, or if they do indulge in nothing more than an exercise in glorified tourism, the arrogance of not asking is stupendous.

So it was appropriate that Martin has launched his book in Darwin first, an event that was attended by family members of some of those people who were around in the communities when the Mountford expedition was there. And I'm really pleased and excited tonight we get to see some footage from that launch in Darwin.

And of course, because it's a historical work, 'Clever Men' necessarily deals with sensitive matters. As I've mentioned, these histories are sometimes difficult, but they are a necessary part of truth telling and a deeply important aspect of our national history and our national story. Throughout the book, the reader is guided by Martin's careful narration, which interprets this material within its historical and cultural context. In fact, Martin's entire book reflects his understanding of the need for consultation with First Nations people and his respect for the protection of cultural practises and knowledges.

A most moving part of the book describes the repatriation of remains back to community. And it's a really important part of the story. By including this material Martin's book serves as a warning of the hurt that can occur when First Nations communities are not consulted and of evidence of the wealth of wonderful things that can occur when they are.

Martin's book is a fascinating page turning account of the relationships between those involved in the expedition and with those that the expedition intended to study. But it's also a fascinating exploration of the forces that led Charles Mountford a telephone mechanic from Adelaide with a side interest in anthropology, that led him to boarding a RAF aeroplane to the United States and later on leading an expedition of American and Australian scientists to Arnhem Land to study traditional Aboriginal life.

One of those forces was when Mountford was boarding the raft plane to America in December, 1944, beg your pardon, when demands on military resources were at their peak. He was travelling however, at the request of the Orwellian sounding Department of Information, and he had a letter of introduction from the then Prime Minister John Curtin. And this is just the beginning of this extremely well-researched and fascinating story.

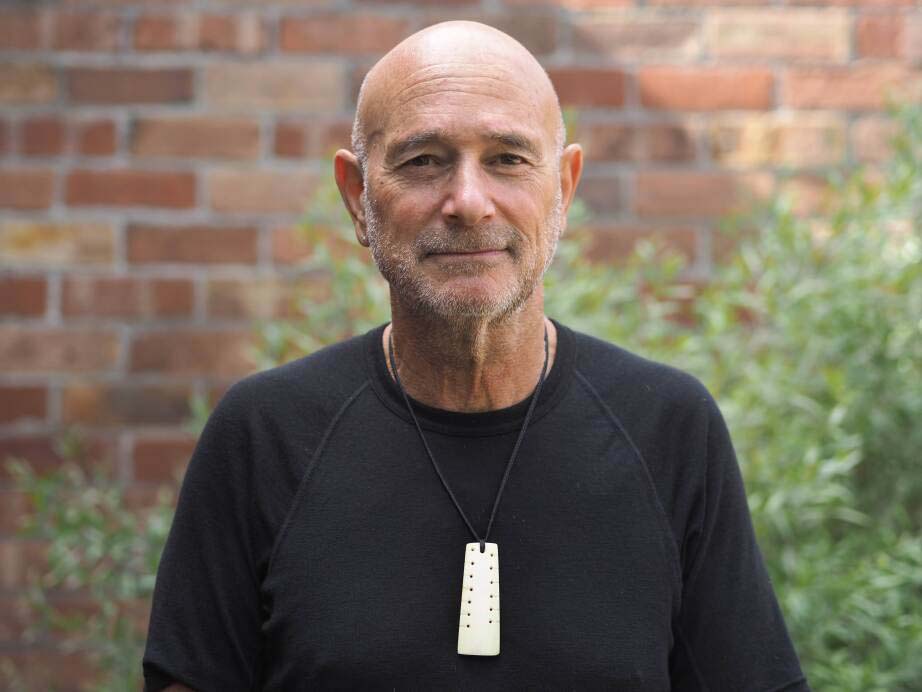

So it is my very great pleasure to introduce our guest tonight. Martin Tom is a multi-award winning researcher, essayist, documentary maker and oral historian who records regularly for the National Library. He teaches at the Australian National University where he holds a chair in the School of History. His deep interest in cultural landscapes and cultural encounter led him to the American Australian Scientific expedition of Arnhem Land of 1948, the subject of 'Clever Men'.

John Altman is an economic anthropologist who has undertaken grounded research in western and central Arnhem Land since 1979. John has been associated with the ANU since 1978 where he established a centre for Aboriginal economic policy research in 1990 and was its foundation director until 2010. He's currently with the school of Regulation and global governance. John's abiding focus is on the articulations between customary and contemporary economic arrangements that sustain indigenous livelihoods throughout remote Australia. Some of his earliest ethnographic research engaged with empirical findings from the American Australian Scientific expedition to Arnhem Land. Since 2010, he has been a non-executive director of the Karrkad-Kanjdji Trust Trust an environmental philanthropy organisation that works closely with ranger groups in Arnhem Land to maintain a globally significant biodiversity and cultural values of their lands.

So please join me in warmly welcoming Martin and John to discuss Martin's book, 'Clever Men'.

Video speaker 1: They would wait until someone died. They would get their old bones and then they would take them up onto the hill and put them in cave. And they would put them to sleep then in their own country, in their own territory.

Video speaker 2: [Speaking in language]

Video speaker 3: Expedition to Arnhem Land.

Video speaker 4: Many, many thousands of indigenous people from outside the United States were collected. Indigenous bodies were especially prized.

Video speaker 5: When I heard that was happening, these people were taken away, I thought, okay, how about them and their spirits? This is their land. This is where they should be buried and left.

Jon Altman: Good evening everybody. I had like to begin by thanking Martin for the invitation to be his interlocutor this evening. Thanks to Aunty Violet for the warm welcome on a very cold evening. And thank you Rebecca for the introductions, and the National Library for hosting this event to launch and honour 'Clever Men', what is, in my view, an exceptional book.

For those who have not read the book yet, it is a masterful culmination of nearly 20 years research and engagement about the formation undertaking and importantly, the aftermath of the American Australian scientific expedition to Arnhem Land, led by Australian polyglot Charles Mountford. A rather controversial figure in the Australian intellectual community. Over 9 months. In 1948, a team of 17 biological and social scientists and recorders visited 3 main sites in coastal Arnhem Land adjacent to colonial outposts at [unclear] on Groote Eylandt, Yirrkala in northeast Arnhem Land and Gunbalanya or Oenpelli in western Arnhem Land.

While words like scientific, expedition, even Arnhem Land land are evocative, what did they mean? Arnhem Land was an Aboriginal reserve inhabited by indigenous people, many living in the hinterland or inland beyond the colonial frontier. A region unvisited by the expedition.

Deploying an innovative hybrid form of history, Martin deploys ethnography, interdisciplinarity, and interculturality to forensically and meticulously examine the genesis of the expedition, its everyday practises, the conflicts and rivalries among its members, and importantly, from a contemporary perspective, its relations with indigenous people and its consequences for indigenous and scientific communities. This book is scholarship at its very best, packaged into a highly readable, emotionally charged, deeply engaging 400 page volume. It is a tale laden with new revelations, intrigue, and a fresh approach of the so-called expedition 77 years on.

So Martin, let me begin by asking, how did all this start for you nearly 20 years ago? And how did this project hold your abiding interest for so long?

Martin Thomas: Well, this is a project that was very rich in images, and I think even, there's a single image here that sort of begins to answer your question and very much to do with how it started. Group of Bininj, as people from west Arnhem Land are called, huddled around a machine. The machine is a sound recorder, something that was rather unusual in its day. Sound recording was just becoming portable in the 40s. And so here we have a group of singers. I first came across our recordings made on this machine. Here's a little taste of it.

[recording of singing in language]

Martin Thomas: And I have to say I found it very arresting and I thought, how do you go about trying to understand an object like that? And I suppose I was at a particular turning point in terms of my own research, and I wanted to, rather than come up with necessary elaborate critiques of colonialism, which is something that I'm decidedly against, I thought it would be more interesting to think about this methodologically. And think about how we might be able to take, say copies of this recording from the ABC archive, and take it into communities and work with people in trying to understand it. And so that's what I began to do. In the beginning it wasn't about understanding an expedition particularly. It was really about trying to get media objects, recordings and films and photographs back to places where they can be sort of easily understood.

And of course, things like a sound recording is accessible to indigenous communities often in a way that a written record is not. And so it was from that position of finding a few, discovering a few odd things, recordings and so forth, that I realised that they were generated by this expedition in 1948 led by a guy called Mountford who I didn't know much about. But that really fed into another interest to do with expeditions and exploration. And it's grown from there.

Jon, once I began investigating the expedition. You think sort of the historical past is rather set and you can sort of go back and find it, but in fact, the event kept on developing and evolving. The human remains already mentioned that were taken by this expedition were, it turned out, that there was a big campaign going on around their repatriation, one that was eventually successful.

And so the journey has gone on and on. It's became a longitudinal sort of project. And it continues even now in the process of bringing the book to light and visiting various friends and relatives, some descendants of people who I worked with and interviewed who have now passed away.

Jon Altman: So Martin, we've already heard that Charles Mountford went off to America in 1944, 45. How did he manage to convince the National Geographic, the Smithsonian and the Australian government to support this expedition to actually underwrite what was a logistically complex exercise?

Martin Thomas: Yeah, well, Mountford, as we've heard, did not have an advanced formal education at least. He was an autodidact and by profession, a telephone mechanic. This enraged certain anthropology professors, AP Elkin, Sydney University was his great nemesis. But Mountford, for a start was very gifted with the camera. And he in the 1930s spent a lot of time in Central Australia. He took early colour films of Uluru and Ayres rock, and he travelled with indigenous people [unclear] speaking people on camel in fact.

And he made these movies which people loved. They came to the attention of the Australian government and very, very late in 1944, really beginning of 45, particular moment where the war is almost won, and Australia is thinking about its ongoing relationship knowing that Britain will never be the power that it was. And so they sent Monty, the Department of Information sent Monty as Mountford was known, on basically a propaganda tour screening and lecturing to his films, which as we see are advertised as Australia's stone age men.

And so Mountford was kind of quite progressive in a way in saying that indigenous people were interesting and we should like them and we should treat them well and all this kind of thing. But he did everything in his power to sort of keep them in the stone age and to basically, to privatise them. Anyway, he took that message to the United States and the Americans loved it, absolutely loved it. And people wrote him fan mails, which of course he hoarded, saying, you have the most wonderfully primitive natives. Our natives are nothing like that. They live with just sort of three tools and not even a G-string, this sort of thing.

It went very popular and doors started opening to Mountford. The most important of those early doors was at National Geographic. They asked him to write for them and they offered him basically research money. And the expedition was born at that stage. He then took the idea to the Smithsonian. The Smithsonian agreed to assign scientists, mainly because they wanted to gather collections. Both ethnographic collections and natural history collections from Australia. And so this offered almost a discounted way of doing that. Once he had these two flagship institutions involved, it was very simple to go further and get interest from the Australian government, especially from the America-loving Arthur Calwell, who was the minister for information. And so tying it all up, the expedition was formed and it involved, 17 personnel were involved in total scientists and support staff.

Jon Altman: And that photograph there of there 17 in the planes very evocative, certainly looks like an expedition to me. It sort of looks maybe scientific, but in terms of the expedition, what were they looking to discover?

Martin Thomas: Well, that is the really key question, isn't it? Because in fact, here's the map of Arnhem Land as it appeared in National Geographic with an article by Mountford called Exploring Stone Age Arnhem Land. But we also know that it had been mapped and even mapped in a European sense. And its indigenous mapping goes back many millennia of course. So I think it's really interesting to think about what they wanted to get out of this. And there are different ways of explaining it. Something that helps. I think what the historians of science tell us is that once Australia had been, or the world indeed had been, largely sort of topographically discovered, the idea of the expedition got taken up by science. And so the scientific expedition or the museum expedition, these became major sort of continuations of what you might call an expeditionary tradition. And there's a certain kind of imaginary, underlying an expedition, which is typically a group of people. And it imagines that the world, the zone that it enters into, is there to be discovered. And in a way doesn't have a sort of existence in consciousness until we sort of come along and observe it and make images and demonstrate our various technologies and so forth. And so there's also something there in terms of the anthropological moment that the First Peoples of the earth were still out there to be discovered. And so while the land was in some way known, we could go out there and try and discover the people. But in fact what they encountered was a world in which missions had become established and actually the expedition went and stayed at those missions. They were easy to get to and often they had airstrips that had been created often during the war. So there was easy access.

So what they discovered were people who were had been through the war, which came very close. Arnhem Landers were involved in the defensive operations in the north. And they were people trying to sort of cope in a way with various sorts of interventions in their lives. And there were people doing traditional sorts of things and people who were being pushed into being gardeners or doing other things that were considered more evolved and more virtuous. At the same time they had a vast amount of ancestral knowledge. So you could say that's what the expedition really discovered, but it went against the grain of everything that Mountford had been telling the world about the completely undiscovered Arnhem Landers. And so it was in fact the expedition was dealing with these operational contradictions, which is sort of part of what I find it really intriguing.

Jon Altman: And the title of the book, 'Clever Men'. So the book begins with an enduring myth from western Arnhem Land about the American clever man. [unclear] or clever man. So who were the clever men in your book?

Martin Thomas: Right? This is almost a question I let the reader decide, but I guess I share my view to an extent as well. But sorry, I'm whizzing through a few images here of the expedition itself and the way it demonstrated technology, for example. But this is the slide that I wanted, and you're absolutely correct that here is this lighthouse at a place called Cape Don, and there was a guy on the expedition called David Johnson. He was from the Smithsonian. He was a zoologist, specialised in mammals. And his desire was to go and catch and skin and stuff, perform taxidermy on lots of unfortunate small animals. And he, Johnson was a sort of bit of a loner. He was rather aloof from the expedition politics of which there were plenty. And so he got dropped off at this lighthouse in a boat and he did this long walk down the Cobourg Peninsula, [unclear].

Now Johnson, who you can see there on the right, was a very tall man. It's kind of ironic that he was, before the expedition, he was photographed there in the museum in Melbourne. But this is him here in the field and there he is sort of stuffing what I think is a quoll. And we can just kind of imagine, and you think about this expedition, mostly a big bomb of people, but he's a peculiar individual. For a start he goes out at night to track these animals. He's a very good shooter. He's enormous. He captures attention as a stranger would in such a place. And then he does this thing of skinning animals, stuffing them and sewing them up as if in some way to bring them back to life. And it was this activity that led the local Iwaidja speaking people to think that perhaps he was like their own shamans, their own healers or medicine people who can perform various supernatural acts.

So I think in a way Johnson was then subsequent, further mythologized indeed, but very creatively and in fact incisively mythologized. Because it said that at a later point in his tour, Johnson went into a cave and he stole a man. And what that means is he stole the bones of a man whose name is known, was known to the community, his name was [unclear]. And they noticed that after he'd been through, the bones were missing. We don't really know whether he took them or not, in fact. But the story develops from there.

The Iwaidja assumed that, well, they knew, he went back to Oenpelli where the rest of the expedition were. And then they say that he took them, the bones, in a bag back to America, and it was in front of his bosses and the people who paid him to go to Australia that he opened the bag and this man leaped out, this life force. And this man declared his presence and said, it's me. I'm [unclear]. I'm the person you stole. And the kind of proof to the Iwaidja about this was that photographs of [unclear], supposedly taken in America, sort of found their way back into the community. And this was sort of seen this, the thing that flinched the deal.

And so this is the very complex story of the clever man. Whether Johnson did all that's attributed to him is a matter of debate, I suppose. But in some ways he's like a kind of compound of different figures on the expedition. And it's an allusion to the bone stealing that took place, that was committed by one of his colleagues in fact. Yeah.

Jon Altman: So we've got the American clever man, did we have an Australian clever man? And I guess I'm thinking here of Charles Mountford, the leader of the expedition. How effective was Mountford as the leader? And wasn't there a rebellion, a revolt against him halfway through the expedition?

Martin Thomas: Well, there certainly was, and Mountford, maybe sort of one of the clever things he did in his career. And Mountford is there on the right with all these bark paintings around him. He drew attention to Aboriginal art and he thought it was very positive. And he thought it belonged in art galleries rather than in science museums, which was actually a progressive position for the day. But if you talk to Mountford's colleagues, they say that he collected bark paintings rather too well, and that he put all his attention and energy and in fact the expeditions resources into that at the expense of his teammates.

Frank Setzler, who's there on the left of the photo, was the deputy leader and also the curator of anthropology at the Smithsonian Institution. And so this is quite an exalted position in American science. And so you've got the well-qualified man who's in the right scientific academy and all this kind of stuff, who's being led and presided over by the amateur, so-called amateur. And probably that in itself is a recipe for trouble.

But Mountford was a very difficult guy, a very difficult man. A very narcissistic man in fact. And he was certainly sort of hogging, I think everybody says it on the expedition, and in fact, relations begin to break down. Mountford makes some terrible decisions through lack of planning.

And one of the big ones is that he doesn't make adequate arrangements for transport of all this gear. And you've got a lot of people, like you've got, you had an ichthyologist, a fish collector on this expedition who actually gathered 30,000 fish specimens. They all went into glass bottles, think the amount of glass bottles and things that they were taking, karting around with them. Well, they were on this vessel called the Phoenix, and it was a complete explosion for Mountford. The vessel was underpowered, it was run by an inexperienced skipper. It had been bought for seven pounds as military surplus. And so Mountford put all the gear onto that and some of the personnel, some of the Americans. And amongst its many misadventures, it got stuck on this reef. So they went for months without essential gear. So Mountford was looking pretty stupid as a result of this. And I've heard this from many sides.

Jon Altman: So when one reads the 4 volumes that came out from the expedition published by Melbourne University Press, what's missing in those volumes is anything about the Aboriginal contribution to the expedition. And any of us who've worked in remote Arnhem Land, remote Australia, know how dependent we are on interactions and support from local Aboriginal people. So is it true that Aboriginal people didn't make a contribution or were they just invisibleised?

Martin Thomas: Yeah, well, of course they did make a contribution. And even for these natural history collectors, well, who are the experts on where the birds nest or where theechidnas feed or anything else. They received a great amount of help. And I think the help that they received reflects the fact that there was a great curiosity among indigenous people about this. And there was a willingness to share knowledge. There was also an economy of exchange going on here.

And there was, in fact, a lot of people had moved into missions and settlements because they'd become addicted to the tobacco that was being handed out there. Tobacco is, tobacco became the currency of the expedition. And it's a really interesting example of the way the expedition exploited addiction, in fact. If it was opium, it would be a huge story. But we know that tobacco is almost as addictive apparently.

So there was lots of input, from carrying bags to guidance, to performing ceremonies, sharing knowledge. And all these paintings that we saw in that earlier slide were actually, they were all commissioned. They weren't just sort of existing waiting for collectors to come. They were specifically made for the expedition. So there was enormous amount of interaction going on.

Now, I guess because of the time when I started doing this research, and also due to the terrible life expectancy sort of figures, there were very few people who remembered the expedition. And I only met one person who really knew a lot about it. He was this man, Gerald Blitner, and he had an incredible role with the expedition on Groote Eylandt. He was an interpreter. He'd learned English in a mission on Groote Eylandt, and he spoke the local Anindilyakwa language.

Gerald Blitner was a man of incredible energy, youthful, very strong, very capable fisherman. He had a great friendship in fact developed between him and the expedition ichthyologist. And I think in that black and white photo there, you sort of see something about Jerry who's on the left, and he's just shot this crocodile, by the way, skinned it. You sort of see how he's showing it off, whereas the guy next to him is sort of hiding behind it. And his personality was very like.

I interviewed him at length over many days. And it turned out that he was as fatigued with Mountford as a good many of his colleagues. And in fact, Jerry said to me he was a tyrant. He wanted it his way, his way. One of the things I found really extraordinary is that Jerry, who had access to a lot of resources knowledge, was able to connect the anthropologists with certain elders, senior knowledge holders. He said, well, he stopped giving things to Mountford because he was too objective. He helped the others more. And you begin to get a sense there of how the expedition was in fact, in various ways being steered by the indigenous people who it was working with.

Jon Altman: So we've heard about the stolen bones and the stolen [unclear] ceremony, the unsavoury aspects of the expedition. Can you tell us a little bit about its positive legacies in terms of material culture, in terms of intellectual property? What did the expedition generate that was positive?

Martin Thomas: Well, I think its role in encouraging interest in various forms of indigenous art is really important. And this was both in Australia and the United States. Many of the objects that had been collected by the American, by Setzler were put on tour on an exhibition that went round all sorts of smaller provincial museums in the US. We have the legacy itself of just these incredibly beautiful, historically important paintings. And there's the fact that sort of, not through any intention, in fact, on Mount Ford's part, who really wanted to get as many paintings as he could into the museum he was associated with, which was the South Australian Museum, but the Commonwealth intervened and a certain number of bark paintings or some works on paper as this one on the right is, they went into all the state art galleries. And so this was a very important moment and encouraged people like Tony Tuckson and Roger Kugel famous collectors to continue and to establish further relationships with Arnhem Land artists.

I think probably one of the greatest effect of the expedition on anthropology is the work done by Margaret McArthur, the one female scientist. And that in itself, the gender politics of the expedition I go into in the book. Here, I mean, for the moment I'll just talk about the work she did as she was at that time, a nutritionist. She would later retrain as a result of her Arnhem Land experience and become an anthropologist. But her mission was to mainly work with women and examine the food gathering aspect of their work. And she quantified everything, including the amount of time spent in labouring and survival, as opposed to doing leisurely things and hanging out with your kids and singing and just in fact having fun. And that was enormously influential. I mean, something you know much more about than me because first.

Jon Altman: Whether in 1972 and Marshall Zen's book, Stone Edge Economics.

Martin Thomas: And Stone Edge economics sort of argued for this sort of original, the original affluent society. It was saying that hunter gatherers weren't locked in this long struggle for existence, that they'd actually sort of rather got things sorted rather well. And the Arnhem Land data gathered by MacArthur was absolutely seminal to the emergence of this theory, in fact.

Jon Altman: Back to the negatives, some of the negatives,

Martin Thomas: Well, look, the negatives are all here. And in some ways in the book that we've, sorry, the photo we've put on the cover of the book, you can sort of see Setzler and his swagger and the kind of neo-colonial relationships that he established. Here he's got two teenagers, two very, very young men who were working for him. And because he considered the archaeological work that he was doing, which threw up lots of dust, very unpleasant late in the dry season in Arnhem Land. And so he got his native labourers to do it. He had a mask to protect himself. Didn't have, I mean, it is absolutely shocking when you look at it. But at the same time, he's up on a plateau called Injalak Hill, just outside Gunbalanya doing this archaeological work. And there are crevices in the rock there that are full of human bones, what were called bundle burials, where bones of a person were wrapped up in paper bark.

And it was while his boys, as he called them, it's while these lads were asleep, and Setzler expresses all this quite freely in his diary that he went and raided the burial caves and took bones. And the fact that he also took this clandestine photograph of the boy asleep, is just sort of really intriguing. His name was Jimmy Bungaroo, and my partner, Béatrice Bijon, with whom who made the film Etched in Bone, which goes into this story. We went and met Jimmy Bungaroo in 2014, I think. Unfortunately he had dementia and he couldn't tell us anything. He had no memory of this. But you knew him well.

Jon Altman: Yeah, yeah. From [unclear].

Martin Thomas: He became a well-known and much respected person in his community later in life. And we've been sort of aided by our son. So it's often because of the very detailed research done by the expedition and the level of photography and documentation, we've been able to uncover quite a lot of these stories.

Jon Altman: And moving on, what do you think some of the legacies are for Aboriginal people today from the expedition?

Martin Thomas: Well, I think it's a very mixed legacy from people do try to talk about the positives. They see these photos here, which are taken in Washington, when the Smithsonian finally agreed to release the bones. It's incredible sort of moment to be present at that event. And the ceremony that they performed with the idea of getting those spirits who'd been abducted, wrenched from their country with the bones, sort of back onto, in fact onto Qntas aircraft and back to Australia.

And Jacob [unclear] of Gunbalanya, who's somebody who I interviewed and talked to a lot, led this campaign to get the bones back into country. And this is seen as a great accomplishment. Partly because I think of the internal politics that goes on, the decisions that have to be made about what to do with this sort of thing. And this is something Béatrice and I worked on with our film, and certainly Jacob said before he died that he thought possibly, well, we can see, we develop a model for repatriations and what you might do with bones when they do come back. So these are sort of, in a way, unexpected sorts of legacies. They come from a great negative about the bones being stolen, but they also, they teach us things. And I think that's recognised in communities.

Jon Altman: Coincidentally, on the 3rd of June, when the book was released by Allen & Unwin, Martin and I and Béatrice were at [unclwar], an outstation in Arnhem Land not far from Fish Creek or [unclear]. And we took a copy of the book to the local school, and the kids there were very engaged. They went straight to Google and checked how they could get a hold of the book.

Martin Thomas: They did.

Jon Altman: Ordered one very quickly. But I guess it'd be nice to maybe make a connection between Jimmy and his son, Reggie Wurridjal, see some of his commentary.

Martin Thomas: That's right. And I feel very indebted to the National Library, of course, also to the library and archives of the Northern Territory who hosted a launch, which quite a lot of people in the top end could get to, including Reggie Wurridjal, who is the son of Jimmy Barker. Jimmy Bungaroo. And we just recorded a sort of little interview while we were there.

Reggie Wurridjal (in video): A lot of important roles, role in participating in all the funerals where people wanting him and taking part in all of that, volunteering every time, volunteering with burials and preparing in all of that stuff.

Martin Thomas (in video): And was this traditional way?

Reggie Wurridjal (in video): He did it in a traditional way, getting bones, and especially when somebody deceased, you get them prepared in a paper barl tree and wrapping them up. And then after a while, maybe 4 years time, they put in a cave or in a so-called bunk bush back, they put it in there. And then after a while for years time, they collect the body, the bones when it's all composed, decomposed, and then they collect the bones and they paint it up in red oak. And then put them to rest in, could be in a hollow log or they have ceremonial, they have hollow log or bury them in the caves or in the country.

Martin Thomas (in video): So important part of [unclear].

Reggie Wurridjal (in video): Important [unclear].

Martin Thomas: So I mean it was a complete surprise to me to learn that Jimmy Bungaroo in his, as a mature man had been involved in all this business to do with ceremonial [unclear] of bones and treatment [uncelar] and so forth. And I don't know, it took the prompt of the launch that Reggie felt that he had to say that.

Jon Altman: So just, we are nearly out of time, Martin. But really just to conclude, and without too much presentism, could the expedition have been done differently?

Martin Thomas: Look, I've thought about that many, many times and I think, well, why did it have to sort of take this rather terrible direction that it did? I think it's really clear that Mountford was not a good person to put in charge of something like that. He didn't have the experience.

And there were vast differences within the party. Not just the national differences between Americans and Australians, but between the younger generation of men involved in the expedition who had nearly all been in the war. And they had a really different sense of hierarchy and leadership to what Mountford who had been, he was born 1890, so he was 58, signed the expedition. He'd been too old for the war, his service was going out, showing his movies and things. And so that was one of the differences.

I've talked to lots of people about the human remains collecting or theft. Well, that's kind of what they did in those days. That's true to an extent, but there are a lot of people who didn't do that. I think about photographer Axel Poignant, who I think just 4 years later is going into this same area. He's very happy to document whatever's going on with ceremony or whatever, but he's extremely attentive to what might be secret and what can't be seen by the non-initiated and so forth. And he checked out on that. The last thing he would've done is go and do a bit of grave robbing, as it actually gets referred to as that within expedition records.

So I think there were other models for having a more, in fact, what could have been a more consultative expedition and that could have responded in a more nuanced way to, in fact, the desire that many indigenous people felt to share aspects of their culture. Bbecause they thought this is the only way that we can be understood. And that's why they did what they did. I think the expedition could have gotten wonderful cultural product for its films and things. It could have made wonderful films that didn't have to go into secret sacred ceremony and show that to all the world, which it did in these films that went to primary schools and you name it. So I guess Australia needed to be a bit cleverer than that in terms of its expeditions. It still needs to be a bit cleverer in my view. There's a lot more to learn.

Jon Altman: Cleverer men.

Martin Thomas: Exactly.

Jon Altman: The next volume.

Martin Thomas: Right. Thank you.

Jon Altman: Hey Martin, thank you very, very much for sharing the background to this wonderful book, and congratulations on its publication. I think I just can't recommend it enough to the audience and to a wider readership. Thank you.

Martin Thomas: Well, thanks for your kind words, Jon, and thanks for being a lovely interlocutor. It's been great fun.

Rebecca Bateman: Thank you so very much Martin and Jon. That was just such a fascinating moment of seeing what that moment in time was like through so many different eyes. And I guess exploring what that looks like now as opposed to what it looked like then as well. I think it's a really interesting, very, very interesting thing to do.

Unfortunately, that is all we have time for tonight. But before we thank Martin and Jon, I'd like to let you all know that immediately following this event, Martin will be making his way upstairs to the foyer and kindly signing some copies of 'Clever Men', which he's on sale at the Library bookshop. I'm also pleased to let you know that as Martin mentioned, Etched in Bone, the documentary jointly made by Martin and Béatrice will air on NITV this Saturday evening as part of NAIDOC week. So yeah, that's one to look out for.

If you enjoyed this book launch, we have more events that might also interest you. This time next week we'll be welcoming acclaimed stencil artist Luke Cornish to the Library to launch his new book. Luke, who was born in Canberra and paints under the moniker of ELK, is the first street artist to ever be a finalist in the Archibald Prize, Australia's favourite art award.

And on the 30th of July, a library employee Edmund Goldrick will launch his book an 'Anzac Guerrillas' in the Library Book Shop. Edmond's book is an incredible true story of how a handful of escaped Australian soldiers became resistance fighters, double agents, and spies in Yugoslavia during World War II. And you can book tickets to both of those events and other Library events by visiting our website.

Now, if you would please join me in a very warm thank you to Jon and Martin.

About Martin Thomas

Martin Thomas is a multi-award-winning researcher, essayist, documentary maker and oral historian who records regularly for the National Library of Australia. He teaches at the Australian National University where he holds a chair in the School of History.

His deep interest in cultural landscapes and cross-cultural encounter led him to the American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land of 1948, the subject of Clever Men. After learning about the films, sound recordings, and photographic records created during the expedition, he began taking copies of audiovisual material to Arnhem Land communities. This consultative research process triggered all sorts of memories from senior elders, and it provided a wholly new perspective on the expedition’s most controversial activity: its theft of Indigenous human remains from traditional mortuary sites and their removal to the United States.

About Jon Altman

Jon Altman is an economic anthropologist who has undertaken grounded research in western and central Arnhem Land since 1979. He has been associated with the ANU since 1978, where he established the Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research in 1990 and was its foundation director until 2010. He is currently with the School of Regulation and Global Governance. His abiding focus is on the articulations between customary and contemporary economic arrangements that sustain Indigenous livelihoods throughout remote Australia. Some of his earliest ethnographic research engaged with empirical findings from the American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land. Since 2010 he has been a non-executive director of the Karrkad-Kanjdji Trust, an environmental philanthropy organisation working closely with ranger groups in Arnhem Land to maintain the globally-significant biodiversity and cultural values of their lands.

Visit us

Find our opening times, get directions, join a tour, or dine and shop with us.