Chinese-Australian family history research guide

What information is available

How-to l Chinese-Australian Family History

00:00 - Introduction

Welcome to our webinar on Chinese-Australian family history. My name is Bing.

And my name is Leisa. We are reference librarians here at the National Library.

We would like to start by acknowledging Australia's First Nations Peoples, The First Australians, as the traditional owners and custodians of this land and give respects to the elders, past and present, and through them to all Australian, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

You may be joining us because you've heard the family stories of a Chinese ancestor in Australia or you've come across a document of a descendant with a Chinese name.

Perhaps you've recently discovered a photograph of an ancestor, or even taken a DNA test, or simply just want to learn more about your Asian roots in Australia. Whatever your reason, we hope this webinar will get you started on researching your Chinese ancestors in Australia.

Like any good family history research, you should start with yourself and work backwards.

It is best to work from the known to the unknown. Start by writing your name, your full name, date and place of birth followed by your parent's full name, date and place of birth. Then your grandparents, full name, place of birth and so forth.

01:33 - Chinese name conventions

You might like to watch our five minute webinar and how to start your family history. For more information, visit our Getting Started page found on our Family History Research Guide. To identify your Chinese ancestors in Australia and you will need their names. This can be the most challenging part of your research if your ancestors arrived before the 1950s. Like so many immigrants from non-English speaking backgrounds, names may have been incorrectly transcribed and there were so many different spelling variations in how names were recorded.

Chinese names usually comprise two or three Chinese characters, sometimes four.

A family name goes before given name. Chinese migrants may swap their names around to suit Western conventions.

But if you are having no luck with finding official records using their names, try searching under their first names.

Your Chinese ancestor could have also anglicised their first or family name.

So, keeping the record of different name variations, is important.

It is not uncommon to find Chinese personal names having an 'Ah' or 'A' in Australian records such as Ah Chin or Ah Foon. This prefix doesn't have a meaning.

It's added before a given name in spoken language to express familiarity. It is a very informal way to address a person; just like using a nickname. However, the prefix was often entered into documentation and, in some cases, combined with a given name to become one word.

Children are normally given their father's family name, but a Chinese married woman may have kept their maiden name.

To successfully check your family back to China you will also need to identify your ancestors Chinese names and the villages they originally came from. This can be difficult, but we will talk about some of the resources that might be helpful later in the presentation. Once you've identified or collected all the possible names your ancestors may have used, you can start searching for records, deciding what records to access and where to locate them.

Records created at the time your ancestor was alive will be the most reliable.

Our Family History Research Guide will provide you with a good starting point on what we hold and what resources you can access.

State and Territory Libraries also hold a range of family history resources.

04:05 - History of early Chinese immigration to Australia

Before we delve into useful resources. Let us provide you with an overview of early Chinese migration to Australia to give you a better context of why and how your ancestors may have arrived in Australia.

The first people from China to settle in Australia were probably a very small group of settlers and domestic servants.

Mak Sai Ying is the first documented Chinese immigrant to Australia.

Although it is believed Chinese immigration may have occurred much earlier.

Born in Canton, the now Guangdong province of China, Mak Sai Ying, who was also known as John Shying and a few other names, arrived in New South Wales about the ship, Laurel, in 1818.

In the late 1840s, Chinese laborers were transported to Australia on indentured labour contracts by British Merchant under the, so-called, Coolie Trade as a response to a labor shortage in Australia. The ship Nimrod brought in the first group of 120 Chinese laborers from Amoy, now known as Xiamen on the 2nd of October, 1848.

After that, more and more ships carrying Chinese laborers arrived at different Australian ports.

Amoy, or Xiamen, is located on the south-eastern coast of China in the Fujian province, or Hokkein, as it was previously known. From 1845, it was a major departure port for transporting Chinese laborers overseas. So, those earliest Chinese migrants were generally from Hokkien.

From 1848 to the early 1850s, over 3000 Chinese workers were transported to Australia to boost the labor force here. On arrival they were hired to work in pastoral properties and rural areas. From 1852, the shipment of Chinese laborers was shifted to ports in other areas such as Canton, Macao and Hong Kong.

Therefore, most Chinese migrants who arrived in 1850 and 1860s for the gold rush were from Canton and the now Guandong Province.

This is an 1853 map of China held at the National Library. Canton is in South China, borders Hong Kong and Macao.

The capital city of this province is also known as Canton. But most migrants came from villages in districts such as Sze Yup, that are outside the city.

The majority of Chinese migrants returned to their home villages by the 1880s after the Gold Rush.

By the time of Australian Federation, there were about 30,000 Chinese in Australia. The number of Chinese arrivals arrivals declined significantly in the first half of the 20th century and in 1947 the Chinese population numbered some 12,000.

07:25 - Shipping records

Perhaps the record that most people want to discover is the name of the ship their ancestors arrived on and when it arrived.

Uncovering the reasons why your descendants migrated to Australia can often just be as fascinating.

Did they arrive to try their luck in the New South Wales or Victorian Goldfields? Were they part of the indentured Amoy laborers who worked on pastoral stations in the late 1840s to the early 1850s?

Did they arrive as a crew member on board a ship? Passenger records can be very useful, can be a very useful source of information for family history research. Records could include the passengers full name date, place of arrival, name of ship, age, occupation, country of origin, marital status, a wealth of information for any family historian.

However, early records could be limited to the content and may be confined to the family name and just an initial with no given name or title such a Mr. or Mrs. with no other information. This, of course, can make it difficult to confirm if the passenger record is the person you're searching for. As with any original historical record, mistakes occurred.

This was even more prevalent in passengers from non-English speaking backgrounds. Names could have been misheard due to a transcriber not being familiar with Chinese names or pieces of information could have been misheard.

Passengers sometimes provide aliases and did not always know their age or were not truthful for various reasons: to avoid law or military enlistment.

As Bing mentioned earlier, it was customary for Chinese immigrants to provide their name first, followed by their given names.

So document takers could have recorded the passengers under their first name instead of their family name.

There is a vast array of shipping and immigration records available.

Before you start your research, it is best to have an understanding of how these records are arranged.

Prior to 1924, the administration record recording of shipping and passenger arrivals was the responsibility of Australian colonies or state.

The surviving original records are now held at the State Archives or Public Records Office and are arranged by passenger type, such as an assisted passenger: this is this was when the passenger's fare was paid for by the government or by an employee or a family member.

Or perhaps they were an unassisted passenger who paid their own fare.

Or they could have arrived as a crew member on board a ship. These are just a few passenger record types.

Some state archives, such as the Public Records Office of Victoria and the State Records Office of South Australia, have digitised historical passenger records and have made them freely available on their websites.

Family history databases such as Ancestry and Find My Past have also digitised various Australian passenger arrival records.

You can access these databases on site within the National Library building, or you may want to contact your local library to find out if they subscribe to these databases. From 1924, immigration became the responsibility of the Commonwealth Government. As a result, all subsequent records relating to immigration, passenger arrivals, departure records and naturalisation records are housed at the National Archives of Australia.

The National Archives of Australia has published an excellent online guides. These detailed guides focus on records that would be of most interest to family historians and researchers of Chinese-Australian history.

There is also an abundance of records relating to entry departure, island registration, student records and other travel documentation that was passed to Chinese-Australians during the colonial period through to the 20th century.

These can be highly useful as they may contain Chinese and English names as well as birthplaces or district of origin.

11:50 - Naturalisation records

Before citizenship began in Australia, on 26th January 1949, immigrants from non-British countries could apply for naturalisation. It was not compulsory, but it did offer incentives such as the right to vote and purchase land. Immigrants needed to be in the country for at least five years before they could apply to be naturalised. Naturalisation records often provide a wealth of information for family historians tracing their Chinese-Australian roots.

Generally, records include the full name, date and namer of ship, country of origin, age and occupation.

Naturalisation records from 1904 become a Commonwealth responsibility and records are held at the National Archives.

Pre-1904 naturalisation records for Victoria and South Australia, also held in the National Archives.

You may like to do a name search via our catalog for any digitised records.

Records created before 1904 in New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia and Tasmania are housed by the State Archives. For those whose ancestors were in New South Wales, the Chinese Naturalisation Database, New South Wales 1857 to 1887, hosted by La Trobe University, is part of the Chinese Heritage of Australian Federation Project, may be useful. The university's Chinese-Australian page brings together many useful databases and indexes, including a list of indentured Chinese labourers in prior years identified in New South Wales 1828 to 1856. Explore their resources page to find out more.

13:47 - Certificates of exemption from the dictation test

Certificates of Exemption from the Dictation Test is a wonderful resource for anyone searching for Chinese immigrants.

From 1904 to 1959, these certificate were issued to Chinese people who departed Australia and wanted to return without having to take a dictation test. Once the certificate was issued, the immigrants had three years to return to Australia, not only will the certificates contain a person's particulars, but will also include a photograph and fingerprint. Certificates are held at the National Archive of Australia.

Some are digitised. Here's an example of a certificates for Florrie Lee Hang Gong, found on their website. You can access an online index to Victorian certificates through the Chinese-Australian family historians of Victoria.

14:45 - Birth, death and marriage records

Birth dates and marriage records are a vital part of any family history research.

They can provide important details about your ancestor, such as a full name birthplace, date, age, occupation, spouse, name and family members. Historical death certificates for New South Wales, Queensland and Victoria will even identify where the deceased was born and how long they had been living in the colony.

You never know if a hidden but important piece of information will be on a birth, death or marriage certificate.

Certificates can be purchased from the relevant state or territory births, deaths and marriage registry office.

Search online to find websites. The National Library and State Libraries hold historical births, deaths and marriage indexes. Check out our Australian birth, death and marriage research guide for more information.

15:38 - Cemetery records

In addition to birth, deaths and marriage records, cemetery records, tombstones and burial plots can often provide additional details and may be inscribed in Chinese language within Australia.

Dr. Kok Hu Jin is well known for his dedication to transcribing and interpreting Chinese language inscriptions on monuments and cemetery headstones.

He has published a series of work which includes histories, Chinese cemetery maps, indexes and names, birth and death dates, birth places and ancestral villages. His publications are held by many libraries and collecting institutions throughout Australia and many of his indexes are freely available online through the Chinese in Australia page found on the Family Search website.

16:37 - Electoral Rolls

Electoral rolls can be a great way to find out more about your ancestors.

You can find out the residential address of a person and help locate other family members living at the same address for a certain year.

You can also find out the occupation of a person which may prompt further investigation into business or company records.

As mentioned earlier, Chinese immigrants needed to be naturalised before they could vote or be listed on any records.

The voter also needed to be over 21. The age was lowered to 18 in 1973.

Let's have a look at an example of an electoral roll. Australian Commonwealth Electoral Rolls up to 2008 are available from the National Library and State and Territory Libraries. Some electoral rolls have been digitised and accessible via Ancestry and my past databases each providing different years. As mentioned earlier, you can access these databases on site in the National Library or contact your local library to find out if they subscribe to these databases.

17:58 - Post office directories

Post office directories can be useful as an alternative for electoral rolls, especially if your Chinese ancestors were not naturalised or able to vote.

They were published annually and included a list of people by town streets, name, occupation and business.

We hold directories in print, microfiche and electronic format. You can find a list of directories by state and territory on "Our family history resources" guide, available from our Family History Research Guide.

We have digitised the New South Wales Wise's Post Office directories from 1887 to 1950 and have them freely accessible from home through Trove. Your State Library may also have directories in their collection.

18:40 - Newspapers (Australian/English language)

Newspapers can be a fantastic way to discover an array of information about an ancestor.

You can search for a birth, death and marriage notice, employment or business details, discover residential addresses, find out if someone served in the war, court cases, immigration and property purchases.

Newspapers can also provide a great social history about the area in the time that they lived.

This interview, published in the Adelaide Observer on the 7th of April 1888 with successful Chinese merchant Way Lee, explores topics such as Chinese migration, family structures, the poll tax, the Chinese labor market in Australia, and his public negotiations to supply Chinese laborers to the Daly River plantation in the Northern Territory. The Chinese Wesleyan Mission Minister in Adelaide, Reverend Hargreaves, acts as an interpreter for this interview. It is a great reflection of issues and topics surrounding Chinese immigrants, such as the poll tax that was imposed on Chinese immigrants upon their arrival to Australia.

Our newspaper collections include historic and modern newspapers, accessible online, as well as newspapers in microfilm and paper formats.

You may like to check out our Australian newspapers and overseas newspapers research guide for more information.

We not only hold mainstream Australian newspapers, but also multiple runs of Chinese community newspapers, which we'll go into later.

20:15 - Searching for newspapers

You can find out what we hold in our catalogue. Searches can be made by title or place of publication. If the name of a newspaper is known, search by title.

Such as "Ballarat Courier" and use the drop down button to select the title field and limit search such as to newspapers.

Click on the find button. You will notice results can be refined, using options located on the right side of the screen, such as decade. To locate newspapers if a title is not known, type in a town city, state or country, followed by the word "newspapers", for example, "Perth newspapers" or "Western Australian newspapers", and use the drop down button to select newspapers.

Then click on the find button. You will find results can be limited using options like on the right side.

You can even select newspapers in different languages. One of our fantastic resources for family history research is Trove.

You can search the books and libraries category to try to find out if a library closer to you holds a newspaper title that you're after.

For example, I searched for a Darwin newspaper but didn't know the title. You could simply type "Darwin newspaper" into the books and library category and click on Find, limit the decade that you're after and select the relevant record and scroll down to find a list of libraries in Australia that hold this title. Trove has also digitised newspapers.

Begin with a simple name search such as "Anne Chung Gon" or "Anne Chung Gon + Launceston".

Watch our short "Getting started on Trove" video on the Trove help page for search tips.

22:04 - Chinese-Australian community newspapers (Chinese language)

The Chinese communities in Australia started to publish newspapers of their own voices in the 1890s.

Some early Chinese language newspapers included the Chinese Australian Herald, the first major Chinese newspaper in Australia, which was published between 1894 and 1923 in Sydney.

The Tung Wah newspapers, which was also published in Sydney and Melbourne's first major Chinese newspaper.

The Chinese Times,, which runs from 1902 to 1922. There's a wealth of information about the individual and collective lives of Chinese immigrants in these newspapers. Trove offers access to a digitised version of these earliest Chinese language newspapers. It allows you to browse the newspapers online and search within the newspapers.

Unlike many traditional Western newspapers, they are less likely to publish family notices, but occasionally death notices were placed in these newspapers to notify the community of the death of a person, especially when the person was a notable member of the community. Major Chinese newspapers like the Tung Wah Times were active community organisations. They spoke for the community, organised fundraising activities to support their ancestral homeland in China and performed all kind of social functions to assist the community in various ways.

You will find numerous business notices, shipping timetables, local news articles and various community notices containing information on people's names and villages of origin.

You will be pleased to know that the Tung Wah Times has been indexed in English, which allows you to search without knowing the Chinese language. The Tung Wah newspaper index is also available through Latrobe University website.

24:08 - Chinese-Australians serving in the defence forces

Chinese Australians have served in Australia Defence Forces and made noteworthy contributions during conflicts such as the Boer War, World War One, World War Two, Korean and Vietnam Wars. While there is a long record of Australians with Chinese ancestry serving in defence forces, even prior to the 20th century, at a time when Australian born children of Chinese settlers facing significant racial intolerance, persecution and social exclusion.

Although the presence of Chinese-Australians throughout Australia may not be as well known to the general Australian public, websites such as World War Two Chinese Australian Soldiers Honour Roll created by the Chinese Museum and the Chinese Anzacs published by the Australian War Memorial, honours these servicemen and women.

Defence service records can be accessed from the National Archives of Australia. Simply visit their website and type in the name of the serviceman or woman into the record search box. You may even find a record that you're after is digitised and freely available online. Due to the prejudice some Chinese-Australians faced when trying to enlist, they may have anglicised their names or used the family name of their mother if they were European. This is the reason why it can be useful to keep a list of name variation for your ancestors to keep in mind as you search.

There are a number of wonderful works that capture the Chinese-Australians' wartime. Search of books and libraries category in Trove to find a library closer to you that holds these books or similar ones.

25:57 - National Library of Australia published and unpublished material

The National Library is a great place to start your family history research not only because we provide access to the many archival records mentioned earlier, but also because of our strong, published and unpublished collections that help you gain a better understanding of the Chinese community, their shared memories, and the cultural and historical context that may influence your research.

The library has an excellent collection of published family histories and secondary sources created by scholars, historians and Chinese Australian genealogy organisations. For example, the multi-volume Cantonese Students Record by Dr. Su Mingxian. In the early 20th century, young Chinese were allowed to come to Australia and to study.

Most who came were children or relatives of people already living in Australia and were mostly Cantonese.

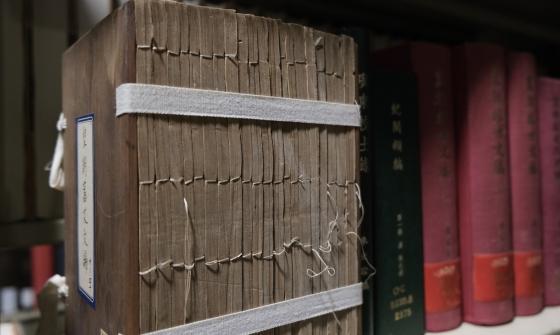

These books to cover biographical information of each student, their family connections in Australia, copies of original records such as students, passports and indexes of the students. This is the first volume of the set focusing on students coming from the Zhongshan District of Cannton. The Library also offers a range of resources about ancestral homelands of Chinese immigrants, including local gazetteers, journals, newspapers and maps.

27:27 - Chinese oral history collection

You may also be interested in exploring the Library's Chinese oral history and manuscripts collections.

They provide a unique insight into the lives and experiences of Chinese-Australian people.

Our oral history collection includes interviews with family members of a number of first generation migrants.

One such interview is with Joyce Lee, who was born in 1916.

She was the daughter of Jin Jiang Henry, the late business owner of Henry and Company.

In her interview, she shared memories of her father, who first mined for tin in Wellborough, in Tasmania, and established his wholesale and retail fruit and vegetable business.

The story of businessmen within William Liu, born in 1893, is just another example.

He describes his return to Australia in 1909 from Hong Kong. He speaks of his studies.

The white Australian policy and his involvement with community matters around Melbourne.

This oral history interview and its transcript is digitised and available on Trove.

Voice of William Liu: Now back to my 1912 to 1914 years in Melbourne.

It was very like, very much like I was back in my father's relatives' Taisin Village.

T.A.I.S.I.N. village. There [Melbourne], you could say I had lead a peasant's life, a village peasant's life very much as if I was born there. I went there, couldn't speak English.

Within months, I suppose, a year or so, I began to feel, you know, one of them.

And so much so., and the dialect that I learned in Taisan was mostly spoken in Melbourne in the Chinese community.

So, I was in my element.

29:35 - Manuscripts collection

Our manuscript collection contain valuable materials such as personal papers, correspondence, diaries and more.

The Letterbooks of Cheok Hong Cheong, include seven volumes of letters by the Chinese missionary.

He was born in China in about 1853 and came to Ballarat in the 1850s with his father, who was also a missionary.

30:04 - Pictures collection

The Library's pictures collection, comprising photographs, prints, drawing, paintings, postcards and objects, much of it digitised, documents the various aspects of the lives of Chinese-Australians.

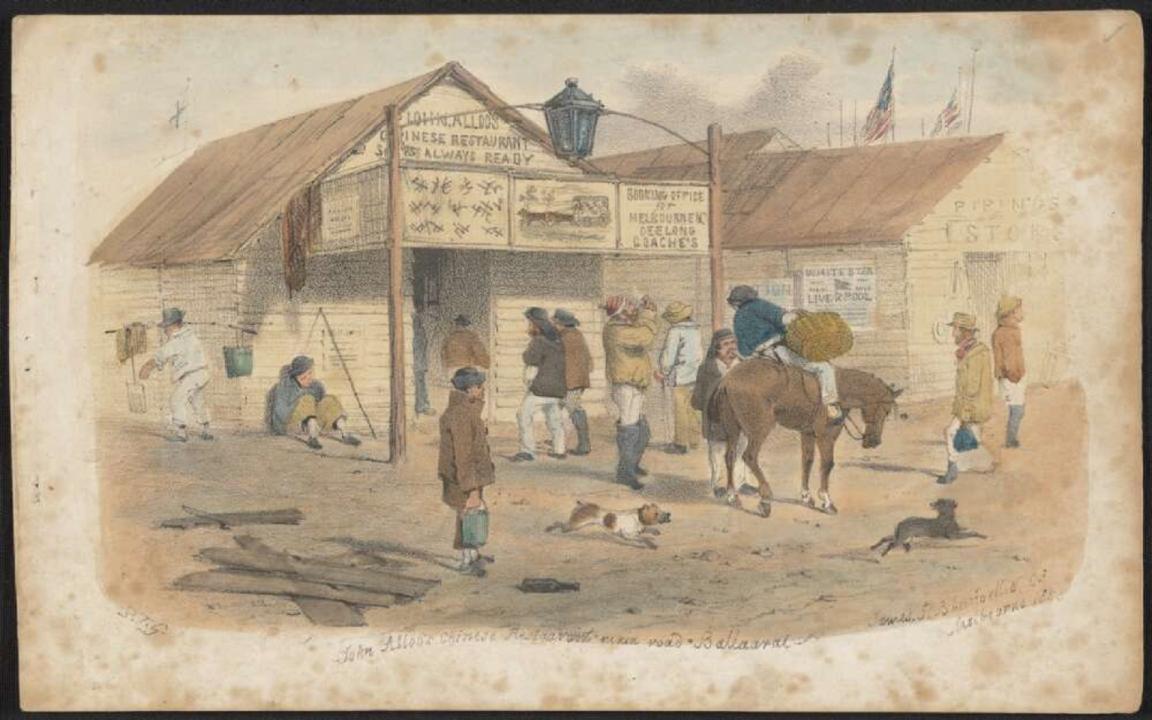

You can find historical images of buildings such as the Chinese boarding house owned by William A Sac, in Gulgong, New South Wales 1872, and John Aloo's Chinese restaurant in Ballarat.

Different Chinese huts and, of course, Chinatowns.

You can also find images that document events such as the Chinese parade in 1901, a Chinese funeral and a puppet show to celebrate the Chinese New Year. There are also portrait photographs of many Chinese migrants.

31:02 - Case study - The family history of Chee Dock and Mary Nomchong

As a case study will explore the family history of Chee Dock and Mary Nomchong, pictured here in 1930.

Chee Dock Ng and Boo Jung Gew married in 1887 in Hong Kong.

This was Chee Dock's second marriage. His eldest son, George, was the son of his first wife who died in China.

We hold a photograph of Boo Jung's wedding dress seen here modelled by her daughter, Ellen, who was also known as 'Nell', shortly after their marriage. The newlyweds arrived in Australia and settled in Braidwood in New South Wales in 1887.

Priorto this, Che Dock had been living in California and came to Australia to join his brother Shoon Foon, born in 1877.

His brother was a storekeeper on the Mongarlowe Goldfields, located just outside of Braidwood and encouraged Chee Dock's move to Australia.

Chee Dock agreed and the two brothers soon became business partners in Mongarlowe. Chee Dock was naturalised in 1882.

The original record is held at the State Records of New South Wales, but we had copies of New South Wales naturalisation certificates in microform format as part of the State Records of New South Wales Archives Resource Collection.

As you can see, his family name was documented as Dock and his first name as Chee.

Chee Dock had returned to China in 1886 to marry Boo Jung.

Like his brother, Shoon Foon, Chee Dock anglicised, his surname from Ng to Nomchong.

His wife, Boo Jung, echoed this and changed her name to Mary Nomchong.

The Nomchong names means 'Southern Prosperity', and it's believed that this was the name of the business which Shoon Foon later adopted as his surname.

Chee Dock took over the Mongarlowe store later and sold the business after his brother died and established a store in Braidwood.

According to articles found on our archive websites, in Trove, this store remained in the Nomchong family until 1980.

You can discover listings for the store in Wallace Street in Wise's New South Wales Post Office Directories up until the 1950s. We hold a photograph of the business taken in 1940.

Those of you who know Braidwood will recognise this building on the corner of Wallace Street.

The sign reads and M. Nomchong and, according to this 1930 article, the company owners were Mary and Chee Dock and their children: Paul, Leopold and Mary M Nomchong.

Chee Dock and Mary had 14 children in Braidwood, raising 13 children into adulthood.

Chee Docks son, George, from his first marriage, remained in China with his grandparents for many years and reunited with his family in Australia as an adult. Although Chee Dock was naturalised in 1882, George was not exempt from the Immigration Act 1901. Consequently, George was deported back to China.

A fantastic 2014 blog by Kate Bagnall titled 'Celestial City: Misunderstanding of the Administration of Immigration Restriction', available in the archived website section in Trove outlines how Chee Dock made a request to the Australian Government that his son be allowed back into the country and even present a large petition signed by the residents of Braidwood, asking for a special consideration to be given.

George was eventually issued with a certificate exemption from the dictation test in 1913, which was extended several times. He remained in Australia until his death in 1970.

The Dr. Su Mingxian books mentioned by Bing earlier revealed an article on Chee Dock held in the Cantonese Student Archives.

According to this article, Chee Dock had applied for a Chinese student passport visa in 1921 for his grandson, Thomas Nomchong, who was George's son. From these documents, Bing was able to determine that Chee Dock's original Chinese family name was, in fact, Wu. In addition to this, Bing uncovered the family originate from the small village of Wenlou in the Xinhui district of Guangdong, China. An unexpected but invaluable find.

Chee Dock and Mary's individual death notices demonstrate how much they would love the respect in the community.

Even in 1977, the Braidwood Historical Society celebrated the centenary of Chee's arrival to the town by organising a community dinner on the 19th of November 1977.

They presented each guest with a souvenir booklet entitled 'The Centenary of Nomchong Family in Braidwood, 1877 to 1977'. There is a wonderful full page article in the Tallaganda Times on the 23rd November 1977 about the dinner.

The article provides a write up about the Nomchong's family arrival to Australia and their history in Braidwood.

Undeniably, this Chinese immigrant family was embraced by the town and, enriched the community by sharing their cultural heritage.

This is just one story across Australia.

36:45 - Collecting Chinese-Australian stories project

We would be interested in hearing your family's immigrant stories.

For more information, visit our collecting Chinese or Australian Stories page.

36:56 - Conclusion and more resources

We have really only be able to scratch the surface, but we hope that this has been helpful to anyone getting started. If you need help moving forward, there are a number of excellent associations with a great deal of expertise such as Chinese-Australian Family Historians of Victoria, Australian-Chinese Community Association of New South Wales, Chinese-Australian Historical Society.

We also have our own Ask a Librarian service. While we can't do extensive, ongoing research for you, we can provide research assistance if you hit a brick wall. Happy researching.

Citation list (in order of appearance):

Foelsche, P. (1873). Chinese wood-carter, Darwin, North Australia. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-141834954

(1895). [Portrait of unidentified Chinese fruit and vegetable hawker with baskets of produce]. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140626205

(1907). Portrait of Maud Shing, Canterbury, N.S.W., 1907. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-147021636

Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate. issuing body. (). A group of young women from the Chinese Youth Group and a girl standing in front of the N.S.W. Railway Institute, Sydney, New South Wales, October 1943 from https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-462437807

Certificates of Exemption from Dictation Test and Hand print - NAA - https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=7461127

Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate. issuing body. (). Members of the Chinese Youth Group having a formal dinner, Sydney, New South Wales, October 1943 nla.gov.au/nla.obj-462438116

(1818, February 28). The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 - 1842), p. 4. nla.gov.au/nla.news-page493698

(1848, July 29). The Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1846 - 1861), p. 2. nla.gov.au/nla.news-page541146

Williams, S. Wells. & Atwood, John M.(1853). Map of the Chinese Empire : compiled from native & foreign authorities. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-1992690410

Grosse, Frederick. (1873). Arrival of Chinese immigrants in Little Bourke Street. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136140335

Shipping Records: Public Records Office of Victoria: https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/explore-topic/passenger-records-and-immigration

Ah See - Naturalisation record - https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/primo-explore/fulldisplay?context=L&vid=61SRA&lang=en_US&docid=INDEX1423102

NLA collection of cemetery records by Dr. Hu Jin Kok: https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/catalog?search_field=author&q=Hu+Jin+Kok

(1909). Wise's New South Wales post office directory. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-522689844

(1888, April 7). Adelaide Observer (SA : 1843 - 1904), p. 26. nla.gov.au/nla.news-page18928849

Guang yi hua bao - The Chinese Australian Herald (Sydney, NSW: 1894-1923) nla.gov.au/nla.news-title704

Chinese Times (Melbourne, Vic: 1902-1922): nla.gov.au/nla.news-title705

Tung Wah Times (Sydney, NSW : 1901 - 1936): nla.gov.au/nla.news-title1184

Kennedy, Alastair. (2012). Chinese Anzacs : Australians of Chinese descent in the defence forces 1885-1919. [O'Connor, A.C.T : A. Kennedy]

Chiu, Edmond. & Soh-Lim, Adil. & Museum of Chinese Australian History. (2021). For honour and country : Victorian Chinese Australians in World War II. Melbourne, VIC : Museum of Chinese Australian History

NLA collection of works by Su Mingxian: catalogue.nla.gov.au/catalog?search_field=author&q=Su+Mingxian

Lee, Joyce Therese. & Giese, Diana. (2000). Joyce Lee interviewed by Diana Giese in the Chinese Australian Oral History Partnership collection.

Liu, William J. L. & De Berg, Hazel. (1978). William Liu interviewed by Hazel de Berg. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-222787139

Cheong, Cheok Hong. (1897). Letterbooks of Cheok Hong Cheong,.

Bayliss, Charles. & Merlin, Beaufoy. & American & Australasian Photographic Company (Sydney, N.S.W.). (1872). Chinese boarding house owned by William A. Sac, Gulgong, New South Wales, ca. 1872. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-147977283

Gill, Samuel Thomas. & James J. Blundell & Co. (Melbourne, Vic.). (1855). John Alloo's Chinese Restaurant, main road, Ballaarat. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135291710

(1901). Chinese dragon on parade in Melbourne, 1901. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140811868

(1890). Chinese funeral, Innisfail, Queensland, 1890-1910. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-137088403

Fairfax Corporation. (1935). Chinese puppets for the Chinese New Year, New South Wales, 8 February 1935. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-160384610

Tesla Studios. ([18--?]). Portrait of Quong Tart. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136718152

(1930). Chinese Australian in his market garden, Northern Territory, ca. 1930. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-137943943

(1945). Dragon Ball, Sydney, ca. 1945. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-147022814

([194-?]). Portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Chee Dock Nomchong. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136763383

(1877). Portrait of Nell Nomchong, an early Braidwood settler, wearing her mother's wedding frock, 1877. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136763054

(1889, February 6). The Braidwood Dispatch and Mining Journal (NSW : 1888 - 1954), p. 3. nla.gov.au/nla.news-page10960596

(1940). The Nomchong store, Braidwood, New South Wales, ca. 1940. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-137358816

(1919). Group portrait of the Nomchong family, ca. 1919. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-147019395

Portrait of Maud Nomchong of Braidwood, N.S.W , 18--, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136763161

Many of the core family history resources used within Australia will be applicable to Chinese-Australian family histories. Consult Australian records and resources on:

- birth, death and marriage records

- naturalisation and citizenship records

- gravestones

- immigration, settlement and registration records

- Chinese newspapers

Getting started with family history research?

For tips on tricks on how to find and use key collections and resources, use our family history research guide.

Getting started

Naming conventions

Understanding naming conventions

To successfully track your family back to China, you will likely need to identify your ancestors' names in Chinese characters (not just the pinyin romanisation, which was not standardised prior to the 20th century), as well as their village and district origin.

In Australian records, Chinese people's names were often written down in different ways or may use have recorded little names or school names. It is worth keeping a list of spelling variations and name variations that you find for your ancestor.

Traditionally Chinese names are comprised of two or three characters: a surname character at the front followed by one or two given name characters. For example:

| 海 Hai (sea) | Surname |

| 书 Shu (book) | Given names |

| 云 Yun (clouds) |

It is common for parents to give a child a name and a 小名 xiǎomíng (nickname or“little name”), with the latter usually used in early childhood.

When a child enrols in school, they are given a “school name”.

Family Genealogies 家族 (jiapu) or 族譜 (zupu) and ‘Generational Poems’ 字輩詞

A Chinese genealogy book traditionally recorded the males' names of the family in Chinese. The surnames of wives were also listed followed by the character 氏 shì, which means surname.

Some Chinese families use a ‘generational poem’ to record the lineage of a generation. Siblings and cousins of the same generation would share a generation name (字辈 zìbèi or 班次 bāncì) which was usually the middle character of the name.

- Jia Pu (Chinese Genealogical Record): a more in-depth introduction by the Singapore-based group Chinese Roots

- Use Jiapu to Grow Your Chinese Family Tree: a blog by FamilySearch.

Recommended reading

You can use these resources to get started:

- Journeys into Chinese Australian Family History: an excellent foundation work which includes detailed case studies as wells as advice on researching and working with Chinese language when you don't speak Chinese, and other general family history research strategies.

- Chinese Cemeteries in Australia Volumes 1-14: This series by Dr Kok Hu Jin is a detailed guide describing and translating the gravestones of Chinese-Australians interned in cemeteries across Australia. They also provide excellent background and context for the family historian, tracing surname groups, districts of origin, language groups and more. They are out of print but you can find copies of these volumes in a library near you in Trove.

Naturalisation and land ownership

Before the 1880's, very few immigrants from China obtained certificates of naturalisation and hence would not appear on electoral rolls. Most of those who did were born under British rule in the Crown Colonies of Hong Kong, Singapore, Malacca and Penang.

The requirements for naturalisation broadly included evidence of ownership of a business or possession of assets such as shops, houses or land. were such that many immigrants from China were precluded from obtaining a naturalisation certification under Section 16 of the “Influx of Chinese restriction Act of 1881”, which stated:

“No Chinese arriving in this Colony after the passing of this Act shall be competent to acquire or to hold real estate in the said Colony any law to the contrary notwithstanding unless such Chinese be British subject either by birth or naturalisation.”

Consequently, most buildings constructed by Chinese communities, such as temples, were constructed on leased or crown lands. So early land and property records are less likely to be applicable.

Key sources

You can find applications for naturalisation, including those that were rejected, cancelled or confiscated, in state archives and at the National Archives of Australia (NAA).

For those whose ancestors were in New South Wales, you can try La Trobe University's Chinese Naturalisation Database, NSW 1857-1887.

Immigration and travel records

There are an abundance of records relating to entry, departure, ‘alien’ registration, student records and other travel documentation that was issued to Chinese Australians during the Colonial period through to the 20th century. These can be highly useful as they might contain Chinese and English names, as well as birthplace or district of origin.

Key sources

Prior to Federation, the New South Wales colonial government was responsibility for its own immigration laws and related administration. These records are predominantly held by State Archives and Records New South Wales.

For (mostly) post-Federation records, the National Archives of Australia (NAA) has published guides. These detailed guides focus on records that would be of most interest to family historians and researchers of Chinese–Australian history.

- Chinese–Australian journeys: records on travel, migration, and settlement (1860 to 1975)

- Chinese immigrants and Chinese Australians in New South Wales

You can also find records by searching the NAA's RecordSearch. Use key phrases like ‘Chinese student’ or ‘student passport for records for on Chinese students in Australia. Files often contain a photograph and details in both Chinese and English.

Chinese-Australian ANZACs

There is strong record of Australians of Chinese ancestry have been serving in the defence forces, even prior, during and after the First World War (WWI) when Australian-born children of Chinese settlers faced significant racial intolerance, persecution and social exclusion. In the 19th century it was not unusual for soldiers to enlist under their mother’s maiden name if it was of European origin, or to use an Anglicised alias.

By WWI, thousands of Chinese Australians had enlisted and served, arguably receiving a higher rate of individual awards for bravery than might have been statistically expected. In addition to those who joined the armed forces, many served in the Chinese Labour Corps who worked under the British and French on the Western Front.

Books

- Morag Loh & Judith Winternitz & Australia. Office of Multicultural Affairs, Dinky-di: the contributions of Chinese immigrants and Australians of Chinese descent to Australia's defence forces and war efforts 1899-1988, 1988

- Govt. Pub. Service. [Also available in Chinese under the title Aozhou Hua yi can jun shi lue / 澳洲華裔参軍史略]

- Diana Giese & Courage and Service Project, Courage and service :Chinese Australians and World War II, 1999

- Edmond Chiu & Adil Soh-Lim & Museum of Chinese Australian History, For honour and country: Victorian Chinese Australians in World War II 荣誉与国家: 纪念二战衷心服役的维多利亚州澳洲华裔 (text in English and Chinese), 2021

- Will Davies & Albert Yue Ling Wong & Brendan Nelson, The forgotten: the Chinese Labour Corps and the Chinese ANZACS in the Great War, 2020

Chinese Australian newspapers

Historical newspaper archives can also be a rich source for Chinese Australian history.

See this Trove blog post for more information: A Treasure Trove for Chinese-Australian History

Twelve Chinese newspapers are known to have been published in Australia between the 1850s and 1950s.

Key sources

- The first national paper, the Chinese Australian Herald 廣益華報 (Guang yi hua bao), 1894–1923.

- Tung Wah News 東華新報 (Donghua xinbao), 1898–1902 and Tung Wah Times 東華報 (Donghua bao) 1902-1940 with an English-language index to the newspapers.

- Chinese Times (美利賓埠愛國報 Meilibin bu ai guo bao (1902-03), 愛國報 Aiguo bao (1902–07); 警東新報 Jing Dong xinbao (1907–15); 平報 Pingbao (1917); 民報 Minbao (1919-1922)).

- Chinese Weekly Press (1923–27)

- Chinese Mail (1923)

- Chinese Republic News (Minguo bao) (1914–40)

- Chinese World’s News (Gong Bao or The Bulletin) (1921–42 and 1947–51)

- Sino–Australian Times (1930)

- Eastern Commercial News (1931– ?)

- The Chinese Advertiser (1856)

- The English and Chinese Advertiser (1856–58)

- Australia-China Times (1955–57)

Unlike many traditional western newspapers, these titles were unlikely to publish family notices. However, they included much information on small (including family) businesses and community news. Some of these titles are digitised and available in Trove.

Other sources

Samuel Thomas Gill & James J. Blundell & Co. John Alloo's Chinese Restaurant, main road, Ballaarat, 1855, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135291710

Samuel Thomas Gill & James J. Blundell & Co. John Alloo's Chinese Restaurant, main road, Ballaarat, 1855, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135291710

Get help with your research

Our specialist staff can help you with your research, to locate resources and to use our microform and scanning equipment but they cannot undertake extensive or ongoing genealogical, historical or other research on your behalf.

Find out more in our Information and Research Policy.

If we are not able to help, you can also try: