In Conversation: Until Justice Comes with Juno Gemes, Djon Mundine and Michael Aird

Entry to this event was free and complimentary beverages were served in the foyer following the event.

In Conversation: Until Justice Comes with Juno Gemes, Djon Mundine and Michael Aird

Luke Hickey: Yuma. Good evening everyone. A very warm welcome on a rather chilly night here at the National Library of Australia. And welcome to our in conversation event Until Justice Comes with Juno Gemes, Djon Mundine OAM, and Michael Aird. I'm Luke Hickey. I'm the Assistant Director General of the Engagement Branch here at the Library. And to begin, I'd like to acknowledge the first Australians as the traditional owners and the custodians of this land. I'd like to give my respects to Elders past and present and through them to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, who are here either watching us online or here with us in the room tonight.

We're privileged here at the Library to undertake our work on the lands of the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people. And I especially acknowledge that their custodianship and their ongoing custodianship of this land, which we're meeting in Canberra, and also to the many collections in the many nations that are represented here in our collection that we're privileged to be custodians of as well.

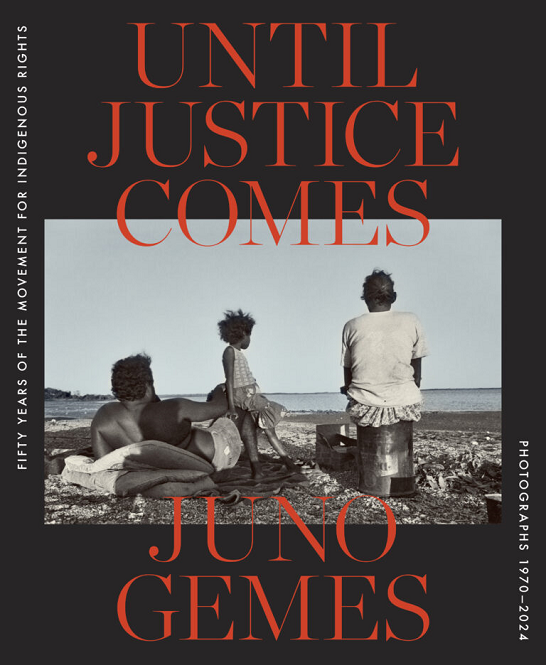

We're here tonight to celebrate the release of Juno Gemes' book 'Until Justice Comes', 50 years of the Movement for Indigenous Rights. It brings together a powerful collection of over 220 photographs, fusing Juno's current and continuing work with her unique living archive. It is the summation of a career witnessing and advocating for change, a collection of photos making visible the history of First Nations peoples struggle for justice over the last 50 years in Australia, providing a visual history and background of the movement leading up to the Voice referendum of late 2023.

This is a landmark publication, based on collaboration, revealing the true history of Australia, the uncovering of the often invisible history of resistance and the fight for self-determination has long been at the heart of her engagement with First Nations peoples, and she has known and worked with those people for over decades and generations as well. It's also a fairly impressive achievement, being able to bring her archive down from an incalculable number of photos to just 220 in the book. So we're looking forward to versions three, four, five, six, seven into the future.

We're also privileged to introduce two of our esteemed guests as well and longtime friends and collaborators, Djon Mundine and Michael Aird, who also joined us for tonight's conversation. John is a proud Bundalong man from the northern rivers of New South Wales. He is a curator, a writer, artist, activist, and is celebrated as a foundational figure in the criticism and exhibition of contemporary indigenous art.

Michael has worked in the arts and cultural heritage for 40 years, with a focus on documenting aspects of urban Aboriginal history. He's currently the director of the University of Queensland Anthropology Museum. Please join me in welcoming Juno, Djon and Michael to the Library.

Michael Aird: Well thank you everybody for coming. It's wonderful to be here with two very good friends of mine, Juno, who I've known since I think about 1990 I think we first met and then Djon since the 1980s, especially going back when I was first starting in this career 40 years ago. It was wonderful having friends like these to prove to me that you can survive in the arts and cultural industry. You can, there is a future, there is a career. Back 40 years ago there was so few Aboriginal people working professionally in the arts and cultural industry and earning a living from it. So it's wonderful to be sitting here all these years later with such good friends.

And also this is the second time Juno and I have been talking about this, we, at the Avid Reader, one of the important bookshops in Brisbane, we spoke about two months ago. and I think just briefly, a lot of the things we covered in that hour was about the importance of ageing arts and cultural workers, about their archives. Where do they end up? And of course, those professional personal archives, they're at risk of not being collected by institutions, not being preserved. But in Juno's case, I know she has a wonderful relationship with the National Library and other institutions. And of course, this book is an important step towards her life's archive being well, I guess preserved and presented and people get to see it. So I hope to call you an ageing arts and cultural professional-

Juno Gemes: Must you. Look, it's an absolute joy to be here. I'm a great advocate of the National Library and I've had a marvellous relationship with it for over 30 years. And so, to be sitting here in this beautiful auditorium, in this great building with two of my comrades from the movement, from way back, forward to the 80s and the 90s, it's just really an honour and a joy.

So 50 years, the last 50 years of the movement for indigenous rights. This is a history that's changed this nation. I think one of the seminal takeaways from the start. I didn't know this at first, what I knew at first was that Aboriginal people were invisible, and the struggle to hold the culture, to save the culture from a colonial regime that wanted to basically extinguish it was worse than even Stanner said.

And so, I discovered in the 70s this not only forced amnesia about our history, but that Aboriginal people were struggling to hold their culture together in communities where they told me, "We're not allowed to speak our culture here. We're not allowed to practise our ceremonies. We'd rather live in a fringe camp", which is actually where I was living with them in 1970 while a researcher on a film called Ruru. So that enraged me and it politicised me in a way that's never left me. And having been ignited, if you like, by a kind of deep respect for the culture, the people upholding it and the difficulty of the situation and the absurdity of it, but just the crass absurdity of it, I realised that people were invisible. And that's actually why I took up a camera.

So unlike so many photographers who, I mean camera is just a tool like a paintbrush or a pen. It's what you do with it that matters and that defines your body of work. So mine started off with an incredible advantage, I think, in that I knew what I wanted to do. The way I could do it, changed over time. And I always tried to work collaboratively with people to understand I was on a learning mission from the get-go until now. And I will be forever, because things are forever changing. And I love that about history where some people will find that scary that we haven't got a fixed history, that history is not fixed. History is never fixed. History is what we all carry within us.

And I'm trying to think now of that quote of what Walter Benjamin's that right at the beginning of the book. Yeah, that "history is about awakening and it really must be about nothing else". So we're constantly awakening to what the truth of this country is. And it's a very complex confronting history. And every country on earth has a conflict history. Show me one that hasn't. So why is it so hard for us to just accept that that's the truth and get to live with it all and accept it all and not try and compartmentalise, this is what people did to each other. And the story of history is still about what people do together, to resist what's been done to them and to try and forge a more equitable society, but also a more informed one. So that that's what I hope this work is.

And really the book is an act of giving back to the communities I worked with and the people I worked with. I hope an honouring, this is what you fought for, for 50 years. I've had the privilege of being with you, of walking with you, of standing with you, of thinking with you, of crying with you, of laughing with you. And this is the outcome and I want you to have it for your children, for your children's children. And that for me is a very satisfying thing.

What was your question? It was around archives?

Michael Aird: Yes. Well, you've mentioned it. This is your contribution.

Juno Gemes: Yeah.

Michael Aird: Trying to get your massive archive out. This is part of it.

Juno Gemes: So what do you do with an archive? There are a group of people in this room with whom a few years ago we had some wonderful conversations about the idea of a national visual history archive, that we dreamt up a whole bunch of us, some of the best minds I could find both within this institution and among the photographic community, among the indigenous community. We all dreamt this thing up, that there could be such a thing as a national visual history archive. Because photography, no matter what form it is, is a visual history of its time. It's the nature of the medium, you can't avoid it. And so that gives it another layer of meaning and value. And just imagine if you could have the work of the finest photographers in one place, then we could really tell the story of this country and understand our history so much better.

So that idea is still alive. It's still out there. We've still yet to throw it on another minister for the arts' desk and hope they'll support it. But I just wanted you to know about it. And that's my kind of dream about archives.

And part of that archive that. So Michael came and helped me organise my archive in the early 90s. I got a grant from AIATSIS and somebody, some kind person, this was about 30 years into the whole project, said, "How's that archive of yours? How are you managing it?" And I said, "With great difficulty." And they said, "That's what we thought. You better have a grant." So they gave me a grant and my great good fortune was I pulled in Michael, who's a genius at organising, our visual history archives, photography archives. This one is a genius at writing about him. And he came up and he helped me put it in order. Jo Driessens came up as a young photographer. I threw her into the dark room. We printed up 1,200 prints and we created a database.

And that was the foundation of me doing the work I've done since then because it organised my work. The truth is that an organised archive is one you can create from. A disorganised one, God help you. So it's, invaluable. It's so rarely taken into account. And so the truth of the matter is that any responsible photographer is going to work with an archivist to put their work in order to make sure that the information about what they're photographing is there for when I'm not. I don't want anybody looking at a thing with no information on it, who's in it, where was it? What's the historic background, all that kind of thing. It's so important. And this place is a kind of beacon of where that kind of information is collected and valued and stored.

Djon Mundine: No, sorry. I think the idea of libraries being in the wider sense of the word being images as well as other things, images, portraits. They're portraits of people and they're images of people that change and generations and so on. I won't wax lyrically about it, but I think it's really important that the fact that you become visible, as you've said, you become real, you enter the memory, the visual memory of the nation, of the community that we now call the nation. It's really important that people do become visible. They are seen in things. Seen in books, seen in films, and obviously, in the visual record. We, the three of us, seem to have come to been born into a time of great change. And we're here in another time of whatever, shit house change. Anyway, as it looks, we got to make it great again. Thank you. Dare I say it.

So I think in my parents' time, they were people who all had jobs. My parents' generation, they had jobs. They actually came to own houses. They set up as kind of an Aboriginal middle class, if you call it. All my parents and relatives, uncles all took photos of their family, outside of other people taking our photos, they took photos of all of us as we grew up. One day we will. I will grow up. But I think we came to a time when people were starting to be more vocal, more visible anyway. Every great social movement needs its documenter, its storyteller, its biographer. Every great person needs a photographer.

And the famous saying, an Aboriginal family used to be a man, a woman and a child, and an anthropologist. Then became an Aboriginal man, two wives and two children and a photographer. The photographer was recording something that was a wider issue, that was a wider movement of wider national social and political movement and that it had meaning for other people. We weren't fairytale people in fairytale places. People still now talk about the Northern Territory as being, or North Queensland as being some sort of family, fairytale place that no one ever goes to. You read books to your children at night about these incredible colonial places. This movement that we lived in a time of needed to be documented. There were lots of people, Juno and other people who recorded, Madeleine McGrady, Michael Reilly, of course as well. Bishop, of course. They all took photos too.

But this was someone who dedicated herself to the time and the space and the sight of the action, which is the thing. Other people have been at various sites and that, but you've attempted to follow this up. Only came to meet you in the early 80s. So I was still at school before then. Sorry. Okay. I bombed in Canberra. I died in Canberra. But, and I remember you were taking photos of what? An Aboriginal cultural event. Well, you did two. Actually, there was a country in Western, there was an Aboriginal Country Western Festival to start with. And then, we went onto another festival, so to speak, the World Conference of Indigenous People run by the United Nations in Canberra, in this place. I think it might've been the first time I'd been to Canberra, I think for that. And you were taking your recording that time. And then, we then met again and I became aware of other things.

You took photos of Geoffrey Samuels. I was looking at an artwork by him, painting that he did. And you had these photos and we were just talking about it previously about the idea of, in the nation, in the social society here, the art world, et cetera, about people didn't see photographs as being artworks. And I wanted to, I bought the painting for the Art Gallery of New South Wales. I was working there as the Aboriginal art curator, and we purchased Geoffrey's paintings and I put these two photos of him wrapped in the painting that he posed in a performance piece that you photographed.

And I remember putting them on the wall next to the painting and people were asking me, "Are these art? Are these part of the artwork? Are they art pieces?" So they had a problem with photography period as seeing it as art and couldn't put that together. Geoffrey's performance and the actual painting where he'd wrapped himself in the painting to perform. And anyway, we've gone on a lot more since then.

And I was talking with Michael yesterday about another Aboriginal activist and about things that we don't have Aboriginal institutions, we don't have these collections. In the United States and other places, they do have private institutions dedicated to collections. They do have, in the United States, they have a Black History Month every year.

And people, the particular demon or devil or whatever activist, there were lots of people involved in putting that money together to be part of those things. It wasn't that you were either a artist or you weren't, you were a historian or you weren't. Every artist is an historian, every photographer is an historian. And I thought those things, there needs to be these archives.

And they need to be publicly shown, is the other thing. It's no good to have an archive that is never shown or part of curating as what I normally do. And I don't mean the cricket ground or something. The lawn at, for the next cricket match. Boom boom. I think curating, part of, in Germany, I found out there were two types of curators in an art institution. They had a curator of collections who was like a conservator who looked after where they were stored, how they were maintained. They were looked after. And there was a curator of exhibitions. And part of that curator of exhibitions was to make sure that the paintings were seen not only in exhibitions, but in publications, in films, in documentaries, on TV, on radio. They were discussed, they were talked about. And the people in them were brought to light and talked about. And they were the things that, a collection has to exist. It can't just exist. It's no good to say the National Gallery or the National Library or the National Museum has 50,000 books or 100,000 books if they're not accessible.

But just to start an image library that's accessible and shown is something that needs to be done. I know they are building a National Cultural Centre in Alice Springs, and I don't know how that's defined entirely. I haven't had a lot to do with it. But the most interesting thing I find in the world that hardly anywhere on the East Coast you find a national Aboriginal archive.

Juno Gemes: Can I ask you something?

Djon Mundine: Yeah.

Juno Gemes: Djon, in that fascinating roll down the stream, I have to pick you up on a few things.

Djon Mundine: Go ahead. Yeah.

Juno Gemes: It's really been a fascinating exercise to see how photography is regarded in this country compared to how it is regarded in the world. Because I'm European, I keep going back to Europe. I go to America too. And my learning about photography has been endlessly to visit the great museums of the world. You go to the Museum of Modern Art in the New York, you go to the Whitney and there are rooms full of photographers, every photographer of that generation. And those rooms were so powerful and they spoke so powerfully to me.

And John Szarkowski, who was the main curator there for some time, actually came out here at the formation of the ACP. And that was an attempt to sort of shake everybody up and say, come on. Photography is one of the major art forms of the 20th and 21st century. Can we be over this kindergarten kind of stupidity? Is it an art form? Of course, it's an art form. It's a major art form.

And the reason why people say these kind of idiotic things is because they haven't really looked into it. They haven't looked into the history of it from the 18-. Photography, interestingly enough, is sort of, if you start studying about 1830 on to now, you can get a bit of an idea about what people have done with photography and what its history is. And in fact, there is a very strong tradition in Australia.

Like if you look back to one of the first exhibitions that I contributed to, which was after the Tent Embassy, was curated by Wes Stacey and Norell. And they came around and bossed me around and looked through my archive and said, "Let's print this and that and this." And I was like, "Yes, let's do it." And they put together the work of 17 photographers, who for the first time with a text, a really biting text by Marcia Langton who was part of the thought stream of that project. And the idea was, let's tell the story of Aboriginal history through photography and it had a phenomenal success. And that book, you can't get it for love or money.

So it just requires people having a look around the world a little, and seeing what the position of photography is in the major collections. Thank God, the National Portrait Gallery from Andrew Sayers on. He got it. We were great friends. I miss him to this day, but he got it. And he understood the power of photography and he collected it with passion, with curatorial zeal, with discrimination, there is a fantastic collection of photography at the National Portrait Gallery. And it actually Languishes, there hasn't been an active curator of photography at the Art Gallery of New South Wales since Gayle Newton left, really.

I know there've been a few young ones who've had a few months, but I'm talking seriously now. People who have a vision and who want to build up a collection. National Gallery too has been a sleeper for some time, in my view anyway. But it needs the kind of vigilance and curiosity about new work that's being produced that curators give to every other medium. I mean, Djon, you've always incorporated photography in your exhibitions, so there is a clear understanding there that you value it. Michael, you are a photographer as well, and you have contributed immensely to the photographic record of Aboriginal life and activism in Queensland.

Michael Aird: I think part of the reason I've done that is I think parallels, with my interest in historic photos and the way. Obviously in the past, photos were taken by non-Aboriginal people and from basically the early photos were all taken by professionals, wanting to monetize Aboriginal images. And that goes back to the physics of the 80s, and 60s. Aboriginal people were very popular and then, those images were being sent. Negatives were being sent around the world and sold.

Juno Gemes: Kari Ann Lindahl.

Michael Aird: Yeah, licenced to other photographers around the world. So it was about a stereotypical Aboriginal image so that photographers could sell those images. And so little care or bother to document who these people were or even where the photos were taken.

Juno Gemes: I remember we were talking about this earlier, and there was. I mean I do a lot of research as well. And early in the 1980s, somehow I got word of the Tyrell collection, which had belonged to the Fairfax family ending up at a bookshop in North Sydney. And I went and there were all these glass plate negatives of Kerry Anne King right up to about the 1920s. And I sat down on the dusty floor and looked through them, and I was in tears a lot of the time because I always say that if you look at any photograph, the expression on the person's face will tell you everything you need to know about the relationship between the photographer and the subject. It's all there in the gaze.

And in the gaze, what I saw in those glass plate negatives were Aboriginal people being bossed around. Being told to throw on these capes that had nothing to do with their culture, posing in front of Elysian landscapes, the women often looking terrified. And those images are so sad to me, and you are right. These guys were making a business out of doing, "reporting back from the colony" on the First Nations People, although they didn't call them that. I don't even want to go to the language that they used because it's what we all, all three of us reacted to and didn't want a bar of. And we wanted to create a counter-narrative in another form of picture-to-making.

Michael Aird: And as Djon mentioned, there was emerging in the mid-1900s, Aboriginal families with a degree of wealth, a degree of success in the European economic system who could afford photography.

Juno Gemes: But that was for personal use, wasn't it?

Michael Aird: Personal, yeah, but they were documenting their successes. So even early-1900s, Aboriginal people walking into studios as paying customers and in 1920s 30s, Aboriginal people buying cameras. And to me, that's the incredible archive is the Aboriginal archives owned by Aboriginal families. And challenging the racist stereotypes of the earlier photographs. And I think that's where you've come in as well. And you're taking these photographs that just document the ordinary life of Aboriginal people.

I think as we were discussing before, to me there's two audiences consuming Aboriginal history and culture. There's the people who want to talk about Aboriginal massacres and things that happened in the past. And then you've got the, and want to talk about how badly Aboriginal people were treated. In a sense, it makes them feel better to acknowledge how bad Aboriginal people have been treated. And then, you also got the other audience who just wants to see Aboriginal success stories, Aboriginal athletes and Aboriginal performers and that sort of successful Aboriginal. But I think what you've done is bring those two stories together.

Juno Gemes: Well, what's been so beautiful in the process is that you might wonder how I get to all these places and it's really simple, I get invited. And you take, for example, a story we don't talk about very often, but it's story of visiting big marbles at Pukatja. And that was such a personal story, and there's this large web of friendships through the arts among us all, right? So Aku Kadogo a really old friend of mine from, working with AIATSIS since it began, and she did a wonderful thing. She met up with Norah Wood and the law women from Pukatja which was then Anna Bella, wasn't it? And she put on stage one of the first stage plays with a law women on it called 'Ochre and Dust'.

And she got a message from Norah saying, "You need to come see me now." So Aku and I had a coffee and she said, "I can't go alone. I can't drive across the Tanami by myself. Will you come?" I said, "Absolutely, I'd love to come." So off we rocked. We rocked up to Alice Springs. Went to see Linda Revvy. Linda Revvy drew on a napkin, a mud map of how you get from Alice to Pukatja on a dirt road signposted by two tyres, if I remember right. And then, we went to stay with Norah and I slept on the floor in Norah's room, and Norah had every minute of our visit chalked up as to what we're going to do. On this day, we're going to go and get Bush medicine. First of all, we're going to go down into the township of Pukatja.

And this is an extraordinary story because that old people's home where we all stayed, these women had won it. They had said to their community, "That's my sacred site there. I want to be an old person and I want to die looking at it. Build me an old people's home there." And they got it. So we were staying there and the whole place had this, the cultural ethos within that old people's home was fantastic. In the television room, they were watching films of themselves dancing and singing 20 years later, earlier, singing along with it. Stuff like, it was so moving and going around the town with Big Marbles and visiting all the other women who'd been in the show. They hadn't seen each other for 30 years.

Now, here's a sort of indication of the way things can work sometimes. When I met Big Marbles on the veranda of her house, when we went visiting her kids, I said, "Norah, I'd like to do a portrait of you. Do you think we could do that sometime?" She said, "Yeah, talk to me later." So that meant I was on the wait. I'd have to see if she wanted to do it or not. Anyway, we went around, we did all these things, everything she wanted to do for every minute of the day. She sent me out. She said, "That's my sacred site there. I want you to go out there tomorrow morning early." So 4:00, sunrise, I was up there. What a gift though, honestly.

And then on the last day. And Nora, a lot of the old girls, they don't always have time to look after themselves or they need a reason. On the last day, she had her face shaved, she had her hair beautifully combed. She put on her best T-shirt and her sunnies, and she was in a motorised chair as a lot of the women were. And we went out to the spot she chose, and it was like her Gloria Swanson moment. She looked as beautiful as Gloria Swanson, I swear to you. And she said, "There you are. That's it. We're going to do this portrait together, you and me." That's the kind of thing that happens.

Djon Mundine: I'll go back for the benefit of the audience who most probably half of them are your children or whatever, but anyway, or our children, one of them, here or there, or uncles or nephews or aunties. You were talking about, your family comes from really from Hungary. We tried to get someone from the embassy to come here, but because we're just about.

Juno Gemes: Busy.

Djon Mundine: We're having an election and we're going to make this country great again, so that's why I'm very opportune with the election, et cetera, to talk about a national Aboriginal image library, image archive. These things are what makes a country great. Images of everyone, not just prime ministers or ministers.

So I won't lose track here. The thing was, you came from Hungary with your parents, you escaped oppression. You escaped a holocaust after Second World War or during the war. And then afterwards, you came here to escape the communist Russians that came and et cetera. And you come to live in what was we call the eastern suburbs of Sydney, which in those days was not a wealthy place to live. It was actually the slum district.

I had cousins that lived in the eastern suburbs. There were people I went to university with there. This guy's father, he was a taxi driver. They lived in the eastern suburbs. It was a slum district.

And then, you talked about your mother brought this book back, a collaboration between James Avedon and-

Juno Gemes: James Baldwin,

Djon Mundine: James Baldwin and Richard Avedon. Yeah, sorry. Go on. Yes.

Juno Gemes: Yeah. Well look, I think the heart of that matter, which you touched on very acutely in your essay, in the book for which I thank you forever. And it was a fact that being an immigrant child and understanding what genocide was, having a Jewish father and a Catholic mother, nobody needed to explain to me what genocide was, but being like an insider and an outsider simultaneously, which is what I became, but it also freed me. It meant I wasn't carrying the burden of the guilt of Australian history. Martin Sharp, who was a dear friend of mine, said to me during the end of his life, because I kept on taking Aboriginal friends around there. I took David Goebbles around there. They fell in love with each other within 10 seconds, one, Jack Marika, two lifelong friends.

And Martin, towards the end of his life said to me, "I have to say to you that, I want to thank you, but I have to admit that I envied you, that you didn't carry the burden of this terrible Australian history with you, and you were free to go into the Aboriginal world in a way I never felt I was." So there was a great, I discovered that because you think of migrant kids being outsiders with salami sandwiches and all that, it didn't really matter. It had a great upside of a great freedom.

The other part of that was my mother. I come from a Hungarian cultural powerhouse, really, that were very leftist for a very long time and had to get out of Hungary very soon, or our lives were in danger. It's the fact of it. And my mother's two brothers, one was a composer and one was a journalist who ran the voice of Hungary and to Budapest for the Americans for years. And so, she would visit them every year and she'd go to the museum. She bought me back this book called 'Nothing Personal' by Richard Avedon and James Baldwin who went to high school together. They were 17-year-old in the Bronx, and they went to high school together, they're both gay. They had a lot in common. And I do believe that James took Avedon into the Civil Rights Movement, and both of them being very smart, erudite, curious artists and intellectuals, they had a profound effect on each other.

And they did this book that I still, today, it's my favourite book in the world, 'Minds in Tatters', that Tashkent has just re-released it. But what it is, it is both a photographic exploration of all the different layers of American culture from the Daughters of the American Revolution, Allen Ginsberg, Bertrand Russell is in there. The guy who invented the atomic bomb, the Civil Rights Movement, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, the Everly Brothers, Fabian. All the cultural heroes of the time and all these layers.

But what I think they were trying to do, and I've never got to say this before, but I think it's really the truth. They were trying to unpick the disease of racism. That's what James Baldwin's life was devoted to. How can you unpick this illness that divides people from one another, that makes them blind to each other? And that's what that book is about. And it's still a seminal influence to me. I recommend it to anybody who can get hold of it.

Michael Aird: And then you've got to meet James Baldwin.

Juno Gemes: Huh?

Michael Aird: You got to meet James.

Juno Gemes: I did. I did. He gave a talk. I was living in London and he was giving a talk at the ICA. And Bobbi Sykes and I met up, she was in London, and we went to this talk at the ICA. The ICA, Institute of Contemporary Art was really the hotbed of radical thinking in England in the 1960s. Its intersection with art, contemporary art, performance art, writing, everything. It was a powerhouse of a place in those days, in the 60s and 70s was his heyday. And we heard that he was talking there so off we went.

And he gave this really powerful talk, my God, such an eloquent, poetic, powerful speaker. And he was trying to make people responsible about how they used language. And I remember him saying, "Have a look at the Bible, have a look at the words, black and white. White is always the illumination, the arising, the glorious. And black is always the dark, the forbidding, the scary, the horrifying. And then examine the way you use language yourself, because that is also how a position towards your fellow human being is perpetuated."

Anyway, after the talk, there was a cafe at the ICA and there was a conga line of fans, waiting to talk to James. And he had this minder, Joe. Joe had this hat, a really cool hat and Winkle pickers, he was most elegant. They were both the most elegant men. And anyway, my turn comes up and I said, look, I told him how wonderful I thought his talk were and how important it was. And I said to him, "I'm a young photographer, could I possibly have a portrait session with you?" And he sized me up with those eyes that he's got that can see right through to your bone. And he said, "Oh yeah, I'll fit you in between the Times and the Observer tomorrow, come to my hotel."

So I went to his hotel, the Athenian Hotel on Hyde Park there. I had a whiskey with Joe, and then he turns up in this Yves Saint Laurent safari outfit with a brooch, this beautiful mother-of-pearl, it's so elegant, just incredible, elegant in mind, body, everything. Anyway, he said, "Have you ever been on the rooftop of this hotel?" I said, "No, what a great idea. Let's go up there." And he said, "Yeah, let's go up there." So we went up there and I told him that I was a photographer with a movement, and his eyes went like that. And he said, "I want to hear everything tell me." So that was my part of the conversation to report back from the front lines as it were.

And then he told me, "Yeah, I've been looking at this because I'm part of the Committee for Civil Rights. And we've had a correspondence with Aboriginal activists since the 1930s." John Maynard writes about this because his grandfather was one of the people who wrote those letters. So they were always writing and giving each other advice because.

And Mum Cheryl told me too, she said, when I went around with her and did a lot with her in Redfern in the 70s. And for example, the children's services at the base of the Black Theatre, and once we were visiting there, and Jenny Munro and Isabel were running it at that point, under Mum Cheryl's direction. And she said, "You see, we got that programme from the Black Panther Movement. They're looking after their kids. They gave them a decent breakfast so they could concentrate and learn properly at school."

I mean, that's another kind of experience that stayed with me all my life, really.

Michael Aird: And the photo of James is in the book?

Juno Gemes: Yeah, yeah, it is.

Djon Mundine: No, it's great. And the cavalcade of images, if I can say casually, that sort of commentary, it's description. It's just an amazing thing. But you became, you also told me about your particular inspired, inspirational famous photographers. You talked about Lee Miller, who was Manray's model and also photographer as well. And Lee Miller's famous quote about, she said her motto in life was to climb out on a limb and soar it off behind her. Which I think is how she lived her life, pretty out adventurous and not being afraid to do anything and be anywhere.

Diane Arbus was another one who said, they were women of those times post-World War II. What were the people that inspired you here? What Aboriginal people inspired you if you had to name one, because it's difficult to name one person, but if you give us an anecdote,

Juno Gemes: So many people were inspiring in so many sorts of ways. I mean, Michael Reilly, who I adored and was a dear friend. I was telling you, we were discussing this earlier, how the gang in Redfern asked me to set up a Koorie photographer's workshop. And so Chica Dixon, who was a mentor of mine, just gave me three grand to be able to set it up. And I booked up the dark room at the Tinch Heads that Peter Kennedy was running at that time.

Djon Mundine: At Sydney University.

Juno Gemes: At Sydney University, correct. And one of the people who walked through the door was Michael Reilly. The first time I saw him print up, I thought, this guy is a genius because he just bent the laws. He understood the laws of photography, of painting with light, but he was straight away, got it so profoundly that he was turning those rules on his head.

Another time when I was living in Glenmore Road and Jeff Samuels was living with me, and that was the time, around that time, we went to do those portraits of him in the first Bumali Studio. And he said to me, one of his griefs at the time was, he said, "Look, I'm at an art school and I'm the only Koorie at the art school, and it's so lonely, sis. It's so lonely."

And Bob and I said to him, "there's got to be some others, find them." And he found them at other art schools. And then he said, "look, we need to have a meeting. Could we have a meeting at the house?" And we said, "sure, we'll go out." Anyway, so he set up the meeting and I opened the door and there was Tracey Moffat, Michael Wharley and Fiona Foley, and they'd come to have one of the first meetings for Bumali. So Bob and I went out for a couple of hours, came back with a couple of bottles of wine, and it was all good.

But so many people have been inspiring to me. One, Job Marika was a, I would regard him as a teacher, like Larry Langley was. And those law men and the law women, they had a profound impact on my life and taught me so much. Odgoronan Knuckle, I was so honoured to have a French.

Djon Mundine: And they're in the book, of course.

Juno Gemes: Yeah. They're all in the book. They're all in the book. They're all in the book. They're all my friends. They're all my extended family, I think of, they're all in there. But my great good fortune was, and it's also part of the way I work. I don't turn up with a camera and go click, click. I find that repulsive. I wouldn't do it, but I form friendships, I form relationships and it's out of those relationships that these pictures come.

And I have teachers like Odgoronan Knuckle who was just such a magnificent person, a human being of profound wisdom and understanding of political smarts. I mean you, really I've been taught by the greatest political minds in this country. So that all in there.

Djon Mundine: Well, Michael, of course and myself. And I mean that someone who I met about the same time that I met you in the 80s. Earlier on, I met him in '81.

Juno Gemes: Who is that?

Djon Mundine: Michael. And then later through the 80s where he seemed to come to meet each other. We both had an ugly brother of some sort. We had a, everyone says about the ugly sister or whatever the bad sister, well, we had the brother who happened to be on the wrong side, politically in some way. So we had a lot too, in common. But Michael then was looking at that early image of what's called a woman being forced into this photograph. A bachelor girl.

Michael Aird: Marianne from Grafton.

Djon Mundine: And that of course, was very important for Fiona that we talked about, that she used that image. So your work of going back to archives and finding treasures or stories and truths in that, that's something that.

Michael Aird: Well, I guess early in my career, I realised these beautiful photographs, the importance of trying to attach names and turning Aboriginal people, not just into stereotypes, but real people. And I think that's partly why I've taken up the camera with such enthusiasm, because I managed to document things that aren't getting documented otherwise.

And I guess part of it too is I guess it's that whole, I guess I'm an organised person and it's a bit of that left-brain, right-brain artists are quite disorganised people by nature. And then, you've got people that are organised. So I guess you need, the artists need to have those organised people working with them, which you've managed to find as well.

Juno Gemes: Yeah, no, I think the organisation of material is so important. And you can imagine how complex it is in the field, getting everybody's names down, spelling them right. I've always gone by, I've got boxes of field notes, eventually coming here, and that's where I used to write down everybody's name. I'd sometimes write down language group. I'd write the date. I'd write what the event was. I'd write what the political background to the event was. Why we'll be having a ceremony now? What was the purpose of the ceremony? Those kind of fields, and my great fear is, I mean, I've got all this in my head. Not all of it is on the page and I have to get it all on the page while I can. But I agree with you that this kind of contextualization is so important.

And it's part of, Djon talks about the idea of reciprocity in his essay. And that's so true too. And I feel as though because I've been taught so much, that's the exchange. I have to be really meticulous in the way I record the detail of the images and what I do with them. It's always an exchanged agreement to which I am bound for my life. This is, work is to be used for educational purposes. It can be used in the art world, it can be used in publication, it can be used in literature. And these are the, I'm bound by those agreements. And it's very helpful to me that idea that it's something, it's an exchange, isn't it, that you are given.

And you are duty bound as part of this family and that family and this part of the culture and that part of the culture to honour your commitments. And that's what I try and do.

Michael Aird: I notice with context you, I mean essentially it's a book about Aboriginal history, but you've also included portraits of non-Aboriginal people who are part of the Aboriginal story.

Juno Gemes: I think it's very important that we honour people for what they've done in their lives. We all know our allies who have worked in all kinds, whether it's Phillip Toyne who worked for 15 years to get the Uluru hand-back sorted out in the legal bun fight that became the Uluru hand-back. I've just been working on a project there that's going to honour its 40th anniversary. That work needs to be acknowledged.

And Clive Scollay, one of the founders of Maruku Arts, one of the guys who bought video and quarter packs to the Central Desert and inspired Jappaljari Spencer to set up Warlpiri Media. I mean, there have been, i you look at the legal service and the medical service, people had the smarts to say, "Okay, to set up the medical service, we need some doctors. Fred Hollows, where are you?"

Same, same with legal service. Who's that wonderful justice? I knew him really well. Wasn't Justice Woodward? Who was it? Well, Hal Wooden. Hal Wooden, so the legal boys called him in. There've been non-Aboriginal allies like that in almost every field you can name. And I thought it was important to honour their contribution as well. Many of them were gone, but they gave their lives to it and they were proud to do so.

Djon Mundine: I've forgotten you read what we're going to do here tonight. I didn't know whether, when we were going to have audience participation or not. Was that part of it or not? It was. We, Michael and I and Juno could go on, like sons and daughters, heartbreak high forever about the good old days. But you must want to ask some questions. You are obviously from Canberra. You'll all be out of a job next week from tomorrow, and this place will be closed down and turned into a casino by the lake, but you must have some.

Luke Hickey: Perhaps some.

Djon Mundine: Curiosity

Luke Hickey: Perhaps Djon, before you scare all of our audience off, we'll just go through some of the ground rules. We've got time for a few questions. We do have some roving mics that are to the side, so if you've got a question, please pop your hand up. The microphone will come to you so we can hear it on the hearing loop here and also on our stream. And we'll get some questions and some time with our panellists.

Djon Mundine: There's Chatham house rules, whatever you say, it won't be on the front page of the Australian tomorrow.

Audience member 1: Hello, Juno. Thank you. I wanted to ask, how do you, for a sitter that doesn't know you, how do you make, for a sitter that doesn't know you, how do you approach them in making them at ease? Or some of your images are certainly portraits in a studio environment, but others are really on the front line. How do you make people comfortable to have a camera in their face?

Juno Gemes: Well, I guess part of the process is that, I mean, Aboriginal people are pretty astute observers, and they very quickly got the idea that she's the one that's there for us. And we know that this leader and that leader and that other one called her in. And so, as you are marching towards Macquarie Street on a land rights march, you talk to people as you have a coffee break or you go and get a beer. You talk to people. I am open and curious and want to know people, and I want people to be at ease with me. But just curiosity and friendliness and openness, I think with a thing. And that kind of message goes like wildfire through a community. And so people would be open with me and not afraid.

And I would, just in those conversations you get with anybody, you're getting to know, you want to get to know people. And you want to understand each other's lives and understand each other as human beings. And that interaction that is so valuable is an essential part of what I do. So most people, I could talk for 15 minutes about every single person in that book pretty much, except for the marches where you get hundreds and hundreds and hundreds and thousands of people and it's not possible. And then, it's like, I mean, this has been and is a movement in which people believe, in which aspirations are expressed, in which there is solidarity, and that is recognised. You are one of us, you're working for us. That's good enough for me, that's the basis on which I work.

Michael Aird: I think we were talking this afternoon about this whole concept, particularly from a government institution point of view. Some institutions expect these incredibly strict rules about photographing Aboriginal people, showing Aboriginal photographs and signed contracts before you can even photograph an Aboriginal person. But really in the real world, you take photos of people and obviously there's a conversation and there's, you don't take the photo unless the other person is comfortable. I find it now, even looking at photos taken a hundred years ago, or whenever, you look at the expression, you can see whether somebody is comfortable about being photographed. You can see there's a verbal agreement there, and you can see whether a person was under stress or not.

And so I think that, and I know even with my own photographs, if someone doesn't look happy, I would never reproduce that photo. It just isn't doing them justice. So you can see the relationships in photos.

Juno Gemes: Lizette had a really good thing about that too. She was one of my teachers, Lizette Model, who taught Dianne Abbas. And I was sent off into a masterclass with her in the 70s, and she said that it's a contract between two people. It's an agreement between two people. You have it verbally, and you also in that sort of mass movement kind of moment have it by eye contact. And I'm at one with Michael on this too. We always have been, agreed on this that if anybody shows with the slightest uncomfortableness or doesn't want it, the camera doesn't go up. It's a basic ethic that's there. Yeah.

Audience member 2: Thank you for the photographs and especially thanks to those who helped you archive them. I agree entirely with what you said about the importance of describing them and having them well-organised. I do a bit of interviewing for the National Library's Oral History Collection, and about 35 years ago, I recorded a bloke in Melbourne named Alec Giacomos. And Alec, one of the great people I reckon, and his wife Merle. But Alec grew up in Fitzroy. Greek background, dark skin, drifted and befriended Aboriginal people in Fitzroy and the community there. Ended up on the tent show scene with Jimmy Sharman and the Bell Circuit as a boxer.

But eventually, he became a manager at Lake Tyers settlement. And in the interview he talks about that, and he told me, I'm mentioning this because of what you said about how the photographs can be used for education and artistically and. But Alec took heaps of photographs of the families at Lake Tyer and with each photograph he took notes, genealogical or family history on the families. And he ended up with a fantastic archive himself.

But this is a case of where the photography and the genealogy attached to it, I believe it was used in a land rights case. So in addition to the educational and the artistic type qualities of the photographs, photographs can be a weapon, a bullet so to speak, in actually achieving an outcome. But again, thanks so much for taking so many photos and for the people who helped you archive them, without which we wouldn't probably know what's what.

Juno Gemes: Thank you so much. In fact, I went to Lake Tyers and I do remember seeing a rather brilliant sequence of photographs there. And I thought there was an old fellow there who kept a kind of museum and he had a whole lot of historic pictures there that were really, there was a second part I wanted to say to you, and I'm just trying to reach for, its a photographer called Lee Chisick, who's been down the South coast for some years, who's done some beautiful work. He did some work with Guboo Ted Thomas and Burnum Burnum. There was something else about that, but I'm just trying to find my way back to it. I don't know if I'll, I was fortunate to find it.

Michael Aird: I talked to Alec Giacomos in the early 90s about his archive. And I was so impressed that he had so many brilliant photographs. Not just Victorian Aboriginal people, but Queensland Aboriginal people. And I said, "How did you get these photographs?" And when he was travelling with Jimmy Sharman's boxing troupe, he said, "At night time, whenever we'd stay in a town, he'd go and camp with the Aboriginal boxers with family." And he took his camera and just documenting. Yeah, he was in a unique situation and he took these photographs. So yeah, so in my early days of, he was such an inspiration to seeing that just what you can do by just documenting what's around you.

Audience member 2: Called every one brother.

Michael Aird: And he was obviously very proud of his great heritage. He said he gets referred to as the Aboriginal who pretends he's not Aboriginal.

Audience member 3: Thank you, all three of you for your wonderful contribution this evening. This is for you, Juno. You came of age at a time when photography was a considered act. You shot on film, you had limited stock. It was very considered. How do you feel about the future photography when we are almost in a saturated age, everybody has a very good camera on them all the time with phones. What do you think the future is?

Juno Gemes: It's a really good question. So I mean, yes, we are living in an age where there is an avalanche of images every day coming at you from your phone, from every Facebook post, from every Instagram post. And it's really important that, I mean, these are visual diaries of people's lives or they're a form of advertising or a mixture of those things that, many purposes to that kind of usage. And it's very different from the considered. I mean, I still long for analogue. I love the dark room, I love film. I love the really, the push and pull of working in a dark room and fighting for an image. And all those qualities which are in the art end of photography, are never going to be there on that kind of usage. So it requires great discernment from all of us to be able to, in a way, sort it out.

And so, you can say, "Oh yeah, that's an Instagram image, and that's an image that was made in an analogue way." The thing you can always go to is what's the purpose? If you ask yourself, look at an image and say, what's the purpose here? It'll give you some clue as to how to sift through it, sift through this avalanche of information.

But on the other hand, I have to admit to you that the convenience and the low light magnitude of a phone. I've been working in Uluru for the 40th anniversary booklet that's going to come out now. And they said, "Let's go out on" They had a project where they're saving the little mala. The mala, little tiny kangaroo has been reintroduced, and the young Nangu rangers are looking after them. I'm saying they're doing room service to the Mala because they look after them so well. Well anyway, so I had to go out with them at night, and even my Leica camera could not cope with just stars. So I used the iPhone and I got really good pictures of the mala who were running around and stuck in the spotlight and all that sort of thing.

So I think you would find most working photographers have a bit of slippage where there is that moment when the iPhone can do it. And so, we're like any other kind of artist. We'll use whatever we can to get the result we need to get. So there is that. You'll find images all over the place, publications, everywhere, that had their origin, and they're going to get stronger and stronger. So the physical weight of a camera, of running around with it, of lifting it to your eye every minute, there's a lot of seductive stuff about an iPhone camera.

But I would urge everybody to keep in mind the long game because what really matters is what's going to last and what's going to speak to the future generations about the time we live in. So if you can keep sifting it through and weighing that up, that might point the way to some of the answer.

Michael Aird: I think something that is changing, particularly in the past from an institutional point of view of very strict rules about what indigenous images can be taken, can be shown, can be stored. And now you've just got, thanks to everybody having these digital cameras in their pocket, that the volume of ... People are just being filmed, photographed everywhere they go. You walk down the street and somebody comes past with a GoPro and films you and you've got no clue where that film is going to end up. But also, you can't spend your whole life worrying about where that film is going to end up. So you just start getting comfortable with it. And then you've got, what did I hear recently, 41 cameras set up in Cunnamulla, on the street looking for crime. Everybody's being photographed everywhere. So I can't say where the, so obviously the rules will change because of the volume.

Djon Mundine: Well, technology's always been a double-edged sword. People become more and more technically efficient at killing people. Remember, people used to shoot people, then they discovered if we put people into a place and we put gas and we can kill thousands at once, whereas bullets cost too much, and take up too much time.

The thing in that, those two novels about the future, what is it? 'Brave New World', the summation of that is that we will be seduced into surrendering all of our privacy and rights by, we'll be providing all our information, because every photo you take is being sifted through and analysed and sent off to a marketing company to know that you like to have margaritas or you like to have, at 3:00 in the morning or you like to have them at 6:00 in the afternoon like I do. So they don't have to pay you. They don't have to torture you to think a certain way. They know what you think and like, and it's so weird in that way.

I think what Juno said then was, about meaning, and what images you take, try to have. People are so casual with imagery.And in other countries, there are not only Kana Muller, that terrible other country, Queensland. Queensland hasn't changed. We used to say it was a dictatorship and whatever. Well, there we are, it hasn't changed. But that in other countries there's cameras everywhere. Knowing where you are at any time of day or night, just you possibly, repression, we will embrace repression. And we'll see that tomorrow at the result of the election. So anyway, sorry. Is there anyone else?

Luke Hickey: All right, there's no other questions. We might draw things to a conclusion then, Juno, I think you mentioned earlier in the night that a camera is just a tool and it's what you do with it that matters and that talking about that capturing meaning, I think listening to Djon you said you could talk for ages. I think we could probably sit here and listen quite happily for ages. We might have to get Barry with his 500 interviews worth of experience to be able to sit down with the three of you and continue that conversation.

But it really has been wonderful hearing about you, all talk about the power of photography, about the importance of those archives, but more importantly, that importance of capturing the culture and the stories, documenting the people's names and the places that you're seeing. And that the community are letting you into and sharing that with you. So thank you for sharing that privilege with us through tonight and through your book as well. Please join me again in thanking Juno, Michael and Djon.

About Juno Gemes

Photographer and social justice activist Juno Gemes has spent much of her long career documenting the lives and struggles of First Nations people. Born in Budapest, Gemes moved to Australia with her family in 1949. She held her first solo exhibition, We Wait No More, in 1982; the same year she exhibited photographs in the group shows After the Tent Embassy and Apmira: Artists for Aboriginal Land Rights. In 2003 the National Portrait Gallery exhibited her portraits of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander reconciliation activists and personalities, Proof: Portraits from the Movement 1978–2003, and has since acquired many of her photographs. Gemes was one of ten photographers invited to document that National Apology in Canberra in 2008. In 2019, the Macquarie University Art Gallery held a survey exhibition of her work, The Quiet Activist: Juno Gemes. Her latest book, Until Justice Comes, is out now.

About Michael Aird

Michael Aird is the Director of the University of Queensland Anthropology Museum. Michael has worked in the arts and cultural heritage sector for 40 years with a focus on documenting aspects of urban Aboriginal history. Photographs taken by Michael have been included in collections such as the National Gallery of Australia, The Queensland Art Gallery/Gallery of Modern Art, the Queensland Museum and the State Library of Queensland. He has curated over 35 exhibitions and undertaken numerous research projects in the area of native title, local histories, art and photography. In 1996 he established Keeaira Press an independent publishing house. He has been published in academic journals and numerous other publications. While not holding an academic position for most of his career, Michael’s research output is significant, being recognised internationally, particularly for the study of photographs of Indigenous people.

About Djon Mundine

Djon Mundine OAM is a proud Bandjalung man from the Northern Rivers of New South Wales. He is a curator, writer, artist and activist and is celebrated as a foundational figure in the criticism and exhibition of contemporary Aboriginal art. Djon has held many senior curatorial positions in both national and international institutions, some of which include the National Museum of Australia, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Art Gallery of New South Wales and Campbelltown Art Centre.

Between the years 1979 and 1995, he was the Art Advisor at Milingimbi and curator at Bula-bula Arts in Ramingining, Arnhem Land for 16 years. Djon was also the concept artist/ producer of the Aboriginal Memorial, comprising 200 painted poles by 43 artists from Ramingining, each symbolising a year since the 1788 British invasion. The Memorial was central to the 1988 Biennale of Sydney and remains on permanent display at the National Gallery of Australia in the main entrance hall.

In 1993, Djon received the Medal of the Order of Australia for service to the promotion and development of Aboriginal arts, crafts and culture. Between 2005 & 2006, he was resident at the National Museum of Ethnology (Minpaku) in Osaka, Japan as a Research Professor in the Department of Social Research and is a PhD candidate at National College of Art and Design, University of NSW. He also won The Australia Council’s 2020 Red Ochre Award for Lifetime Achievement and is currently an independent curator of contemporary Indigenous art and cultural mentor.

Visit us

Find our opening times, get directions, join a tour, or dine and shop with us.