1975: Curator's essay

Written by Guy Hansen, Director of Exhibitions

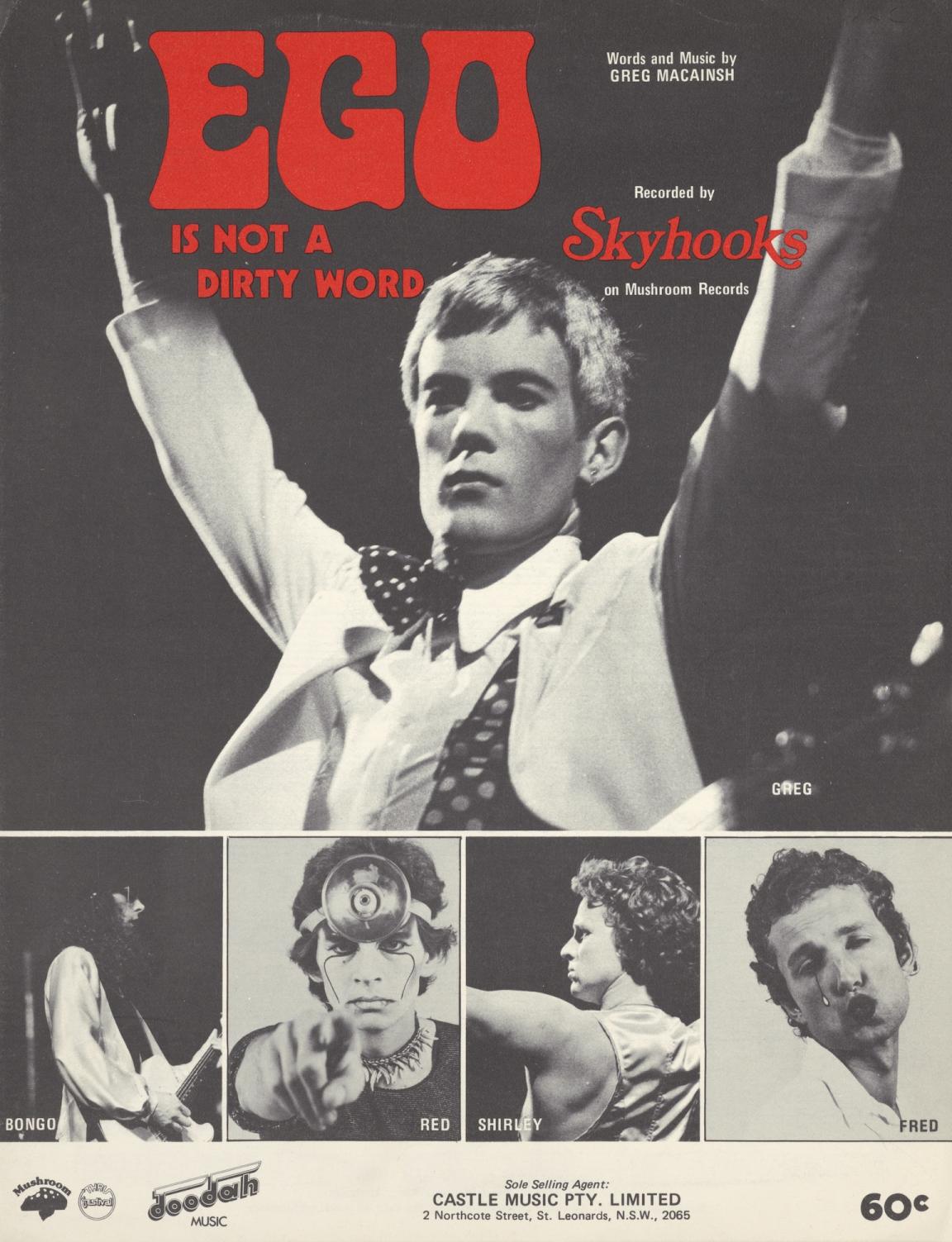

In the classic Australian hit song from the seventies, Horror Movie, singer ‘Shirley’ Strachan describes the experience of watching a horror movie on television only to discover he is really watching ‘the six-thirty news’. Strachan delivered the twist at the end of the song by suggesting, in his characteristic working-class drawl, that all was not right in the world. The song was released by Australia’s favourite glam rock band Skyhooks in December 1974. It went to the top of the charts in early 1975. The album on which it featured, Living in the 70’s, became the highest-selling Australian record of that time, with sales of more than 250,000. Horror Movie’s iconic status was confirmed when it was selected to be the opening song for the first colour episode of Countdown, which was then one of Australia’s most popular television shows, screened on 1 March 1975.

Greg Macainsh, Ego is not a dirty word, 1975, nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn1843249

Greg Macainsh, Ego is not a dirty word, 1975, nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn1843249

Current events

What was it that made Strachan liken the seventies to the experience of watching a horror movie? Mid-decade news broadcasts were filled with stories of disasters and political crises. On Christmas Day 1974, Darwin was hit by Cyclone Tracy. Wind gusts of more than 200 kilometres per hour destroyed over 80% of Darwin and killed 66 people. The new year saw the grim task of evacuation and recovery begin. The news did not improve when, on 5 January 1975, the bulk carrier SS Lake Illawarra collided with the Tasman Bridge in Hobart, collapsing its central span. Five cars plummeted into the Derwent River below and the Lake Illawarra sank within minutes of the accident. Twelve people died in the catastrophic collision. Hobart was split in two, with residents of the eastern shore of the Derwent isolated from the main part of the city, as the long process of rebuilding the bridge got under way. The bridge would not reopen until October 1977.

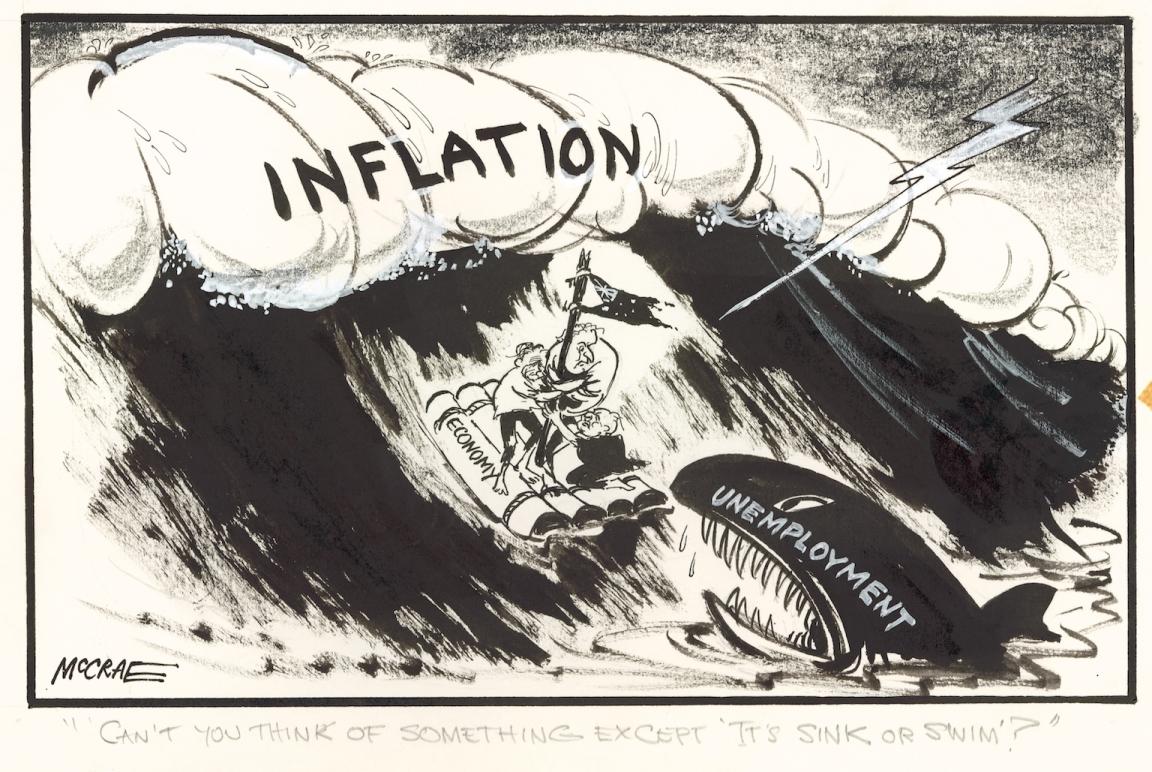

International news was also filled with historic stories. In 1974, the world watched as the Watergate scandal unfolded in the United States, culminating in the resignation of the embattled President Richard Nixon. Governments around the world grappled with simultaneous stagnant economic growth and high inflation, or ‘stagflation’, and an energy crisis, as the price of oil rapidly rose. In the early months of 1975, the news also focused on the recent offensive by the North Vietnamese in the Vietnam War. Australian combat cameraman Neil Davis was there to document the moment when a Soviet-made T-54 tank smashed through the gates of the Presidential Palace in Saigon on 30 April 1975, signalling the capitulation of the South Vietnamese government. Revolutions and conflicts erupted around the globe as the long tail of colonisation in Africa and Asia continued to unfold. As the ‘Carnation Revolution’ in Portugal toppled the Estado Novo regime and installed a new government in 1974, the country’s colonies, including Mozambique and Angola, became independent. As the Portuguese withdrew from East Timor, the East Timorese people briefly experienced independence, only to have the Indonesian army invade and annex the territory in December 1975. East Timor would not fully regain independence until May 2002, when it became the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste.

Stewart McCrae, "Can't you think of something except 'It's sink or swim'?" [Gough Whitlam, Jim Cairns and Frank Crean on a raft called economy, about to be overcome by inflation and unemployment], c. 1970, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-145832435

Stewart McCrae, "Can't you think of something except 'It's sink or swim'?" [Gough Whitlam, Jim Cairns and Frank Crean on a raft called economy, about to be overcome by inflation and unemployment], c. 1970, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-145832435

Politics

Australian politics was also riven with drama in 1974 and 1975. The Whitlam government narrowly survived a double dissolution election on 18 May 1974. This set the scene for a historic joint sitting of parliament in August 1974 which passed key legislation, including the creation of two Senate seats each for the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory, and the establishment of Medibank, a public health insurance scheme for all Australians. Reforms continued in February 1975 with the introduction of a new Australian honours system, replacing the imperial system.

In June 1975, parliament passed the Racial Discrimination Act, outlawing discrimination on the basis of race, and the Family Law Act, which created the Family Court of Australia and provided for no-fault divorce. The government also passed the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Act 1975, which provided for the protection of the Great Barrier Reef.

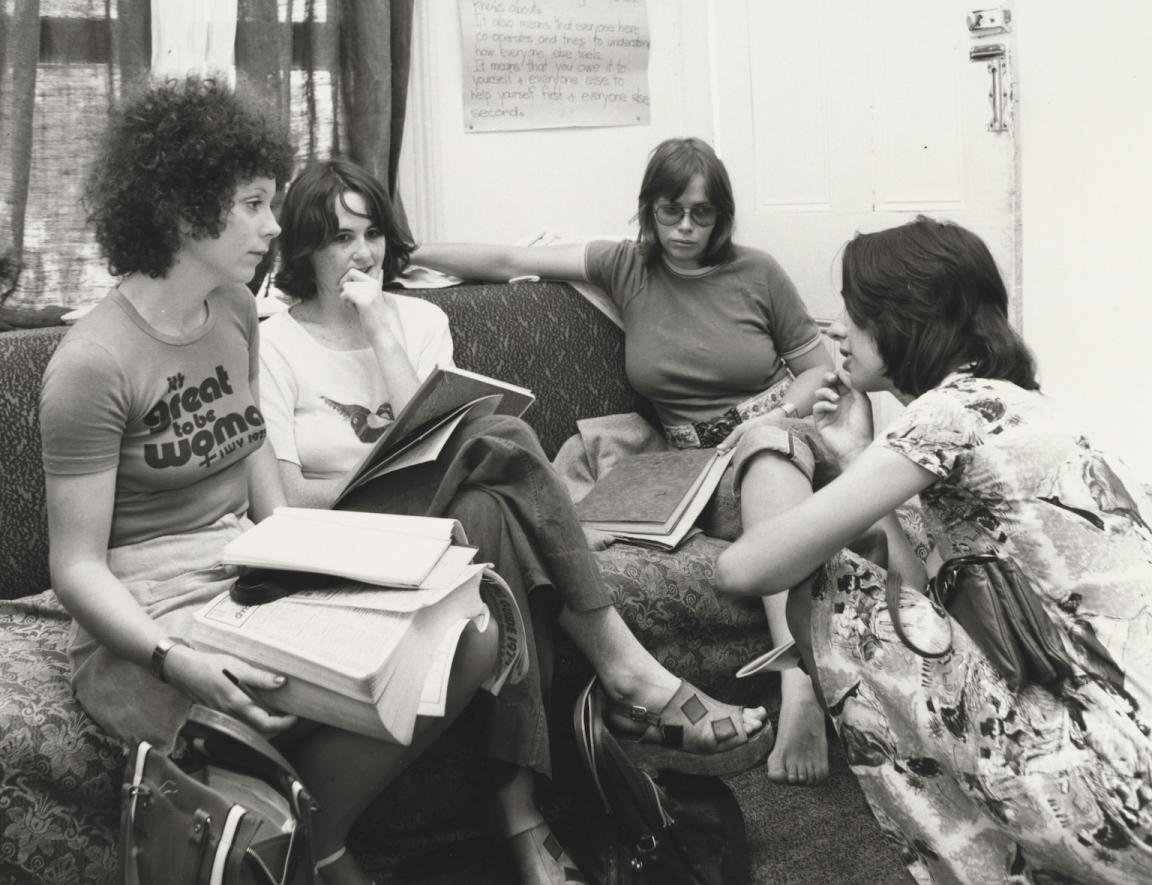

The Whitlam government was also responding to the demands of the women’s liberation movement. The strength and vibrance of the movement in Australia was seen on International Women’s Day on 8 March 1975 when more than 5,000 people marched from the Domain to Sydney Town Hall. Activists were calling for better access to contraception, sex education and abortion rights and campaigning against discrimination in the workplace. They also wanted to draw attention to the endemic problems of sexual and domestic violence.

A key leader in the movement was Dr Anne Summers, the author of Damned Whores and God’s Police, the classic feminist history of how women’s roles in society had been stereotyped. In 1974, Summers and other activists occupied two vacant houses in Sydney and established the Elsie Women’s Refuge Night Shelter. In January 1975, the Whitlam government provided one-off funding for the shelter, and by the end of the year more shelters had been set up in cities around Australia.

The Whitlam government also appointed Elizabeth Reid as Women’s Advisor to the Prime Minister, the first such position in the world. Reid helped push for equal pay for women, paid maternity leave in the public service, benefits for single mothers and the funding of community childcare centres. She also led the Australian delegation to the UN’s World Conference of the International Women’s Year, held in Mexico in June–July 1975.

Australian News and Information Bureau, Staff assisting women seeking refuge at the Elsie Women's Refuge shelter for women, Sydney, 25 February, 1975, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-661792766

Australian News and Information Bureau, Staff assisting women seeking refuge at the Elsie Women's Refuge shelter for women, Sydney, 25 February, 1975, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-661792766

The 1970s were also a time of rapid change in Australia’s attitude to migration. The Whitlam government articulated a new vision for a multicultural Australia in which migrants from diverse cultural backgrounds were celebrated for their contribution to Australian society. The migrant intake began to become more diverse, particularly with the influx of refugees from Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia after the end of the Vietnam War. Political unrest and conflict in East Timor, South America and the Middle East also prompted many to seek protection in Australia.

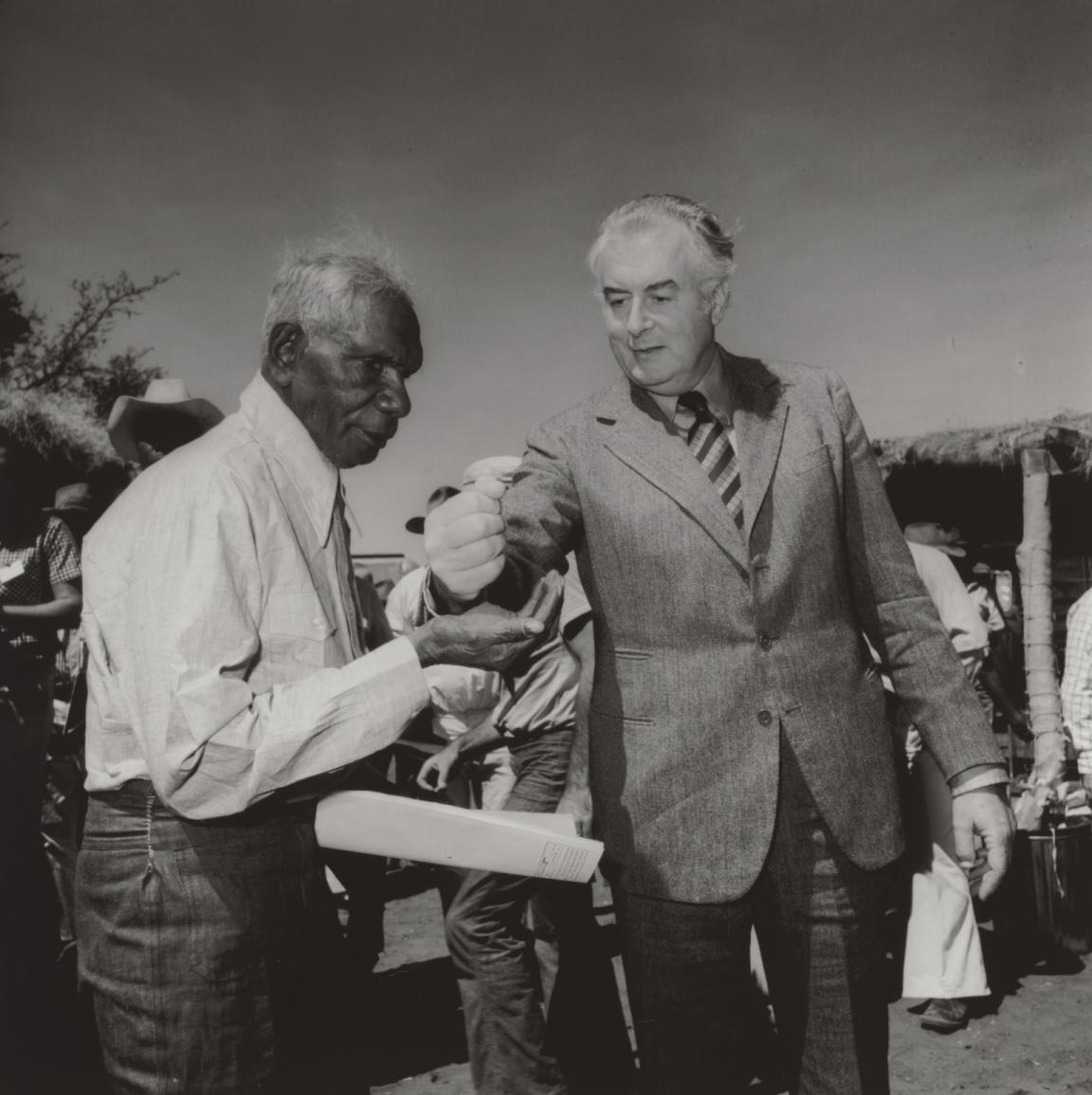

1975 also saw the culmination of the campaign for land rights for the Gurindji people at Daguragu (Wattie Creek) in the Northern Territory. What became known as the ‘Wave Hill Walk-Off’ began as a strike by Indigenous pastoral workers on Wave Hill cattle station for better pay and conditions in 1966 and evolved into a struggle for land rights which would dominate Australian politics for years to come. In 1967, Gurindji elder Vincent Lingiari petitioned Governor-General Lord Casey for land to be returned to Indigenous ownership. The campaign gathered strength with support from activists including the writer Frank Hardy, who helped organise protests in Melbourne and Sydney. In 1971, Lingiari, Galarrwuy Yunupingu and Ted Egan released the single The Gurindji Blues, which sold 20,000 copies. The strike continued until 1975 when the Whitlam government negotiated an agreement with the owner of Wave Hill Station, Lord Vestey, to lease 3,236 square kilometres to the Gurindji people. On 16 August 1975, Indigenous photographer Mervyn Bishop captured the moment when Prime Minister Gough Whitlam poured a handful of red dirt into Vincent Lingiari’s hands at a ceremony at Daguragu, symbolising the return of the land to Gurindji ownership. This successful campaign would be the first step toward the development by the federal government of land rights legislation for Indigenous Australians.

Mervyn Bishop, Prime minister Gough Whitlam pours soil into the hand of Gurindji Traditional Land Owner Vincent Lingiari at Wattie Creek, Northern Territory, 16 August 1975, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-153513023

Mervyn Bishop, Prime minister Gough Whitlam pours soil into the hand of Gurindji Traditional Land Owner Vincent Lingiari at Wattie Creek, Northern Territory, 16 August 1975, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-153513023

Further north, self-determination was also being returned to the First Nations people of Papua New Guinea. The Australian Government had administered the former British territories of Papua from 1906 and of New Guinea from 1945. On 9 September 1975, the Papua New Guinea Independence Act received Royal Assent and, a week later, in a ceremony attended by HRH Prince Charles, Michael Somare was sworn in as Papua New Guinea’s first prime minister.

While the Whitlam government was implementing its program of reforms, it also found itself mired in a rolling series of political controversies. One story that dominated the media for much of 1975 was the so-called ‘loans affair’, in which the Minister for Minerals and Energy ‘Rex’ Connor engaged a mysterious London-based Pakastani commodities dealer, Tirath Khemlani, to negotiate a massive loan to invest in developing Australian mineral and energy resources. When Khemlani failed to provide any evidence of progress in sourcing the money, the government withdrew Connor’s permission to seek the loan. However, after news leaked out that Connor had continued to liaise with Khemlani, Whitlam dismissed him from the Cabinet for misleading parliament. The opposition, led by Malcolm Fraser, used the loans affair to argue that the government had acted improperly. This controversy, combined with rising inflation, unemployment and economic stagnation, provided the pretext for the opposition to block the government’s budget in the Senate.

The deadlock in the Senate was dramatically broken on 11 November when Governor-General Sir John Kerr controversially sacked Whitlam’s government and commissioned Liberal leader Malcolm Fraser as caretaker prime minister. A federal election held shortly afterwards, on 13 December, confirmed the Fraser government in office. While political power was transferred peacefully at the election, Kerr’s dismissal of Whitlam was seen by many as a serious break of constitutional convention that had seriously damaged Australian democracy. On the day of his dismissal, Whitlam denounced Kerr’s actions in one of the most famous speeches in Australian political history, made on the steps of the parliament: ‘Well may we say “God save the Queen” because nothing will save the Governor-General’.

Australian Information Service, Gough Whitlam speaking on the steps of Parliament House, Parliament House, Canberra, 11 November 1975, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-147274349 and Malcolm Fraser walking beside car at Parliament House, Canberra, 11 November 1975, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-147275242

Australian Information Service, Gough Whitlam speaking on the steps of Parliament House, Parliament House, Canberra, 11 November 1975, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-147274349 and Malcolm Fraser walking beside car at Parliament House, Canberra, 11 November 1975, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-147275242

Pop culture

While 1975 is often remembered for the political disruption of ‘the Dismissal’, it was also an incredibly vibrant time for music, film, television and sport. In addition to Skyhooks’ dominance of the charts, many other Australian artists were finding success. Bands Sherbet and Hush, and singers John Paul Young, Daryl Braithwaite, Olivia Newton-John and Marcia Hines were all on the way to becoming household names. An appearance on Countdown, with an endorsement from the program’s host ‘Molly’ Meldrum, ensured a hit would follow. Live appearances, often lip-synced, or music videos were the show’s staple. Families across Australia gathered in their loungeroom every Sunday night at 6pm to watch appearances by international artists such as Rod Stewart, Status Quo, Queen and ABBA. This helped create a soundtrack for a generation which can still be heard today on the radio.

1975 was also a great time for blockbuster movies. New releases were major cultural events that reached mass audiences in a way that is hard to imagine today. Steven Spielberg’s Jaws left an indelible mark on popular culture. The story of a great white shark preying on holiday-makers at Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts struck a chord with beach-loving Australians. While most of the movie was shot on location, underwater footage of live sharks was filmed at Dangerous Reef in South Australia. For a generation of adolescent Australians, watching Jaws meant that they would carry a fear of being eaten alive in the surf for the rest of their lives. It would become the highest grossing movie of all time until surpassed by a new blockbuster, Star Wars, in 1977.

Another film which had a major impact on young Australians was The Rocky Horror Picture Show, an adaptation of the original 1973 musical of the same name. Combining both horror and science fiction genres, it was a tale of a young married couple whose car broke down on a stormy night, forcing them to take refuge in a gothic mansion. Pandemonium ensued. Punctuated with catchy songs and amazing dance routines, this modern take on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein would go onto become a cult classic shown at late-night sessions in cinemas.

Monty Python and the Holy Grail was another movie that became part of the zeitgeist with its surreal send up of an Arthurian quest. For decades after the film’s release, teenage boys in anglophone countries around the world would compete to recite scenes from the movie verbatim, while their friends and families merely rolled their eyes.

The early seventies also saw a ‘new wave’ of Australian cinema achieve critical acclaim and popular success. Picnic at Hanging Rock, a mysterious costume drama set in 1900 in which a group of schoolgirls disappear on a bush walk, helped establish Peter Weir’s reputation as one of Australia’s most successful film directors. The film’s haunting soundtrack and ambiguous ending provided an ideal conversation starter for 1970s dinner parties. Guests could endlessly debate what happened to the girls and what it meant.

The mid-seventies was also a time when it was fashionable to celebrate Australian working-class culture. Jack Thomson’s portrayal of Foley, the hard-drinking ‘gun’ shearer in Sunday Too Far Away provided the classic depiction of a good bloke trying to make his way in the world. With its affectionate depiction of male mateship, binge drinking and brawling, Sunday Too Far Away reminds us of how much Australia has changed in the last 50 years.

While Jack Thompson was the personification of the Australian working-class male on the big screen, Paul Hogan became the representation of the everyman on the small screen. Starting in 1973, The Paul Hogan Show provided a weekly dose of sketch comedy featuring Hogan and his sidekick ‘Strop’ played by Hogan’s manager, John Cornell. A mixture of slapstick, sexism and larrikinism, The Paul Hogan Show was originally broadcast on Channel 7 and then Channel 9, running until 1984. Hogan was also the celebrity brand behind the ubiquitous cigarette advertising campaign, ‘Anyhow, have a Winfield’. His smiling face, with a requisite pack of Winfield Reds, could be seen everywhere in print, television and billboards. Hogan’s personification of all things Australian would continue into the 1980s, when he became the face of the successful Australian Tourism Commission campaign, ‘Throw another shrimp on the barbie’, and as the fictional character Mick Dundee in the 1986 hit movie Crocodile Dundee.

In contrast to Hogan’s populist entertainment, the Australian Broadcasting Commission (later Corporation) was a haven for more experimental comedy, producing programs such as The Aunty Jack Show and The Norman Gunston Show. Aunty Jack was set in the industrial city of Wollongong and featured a violent crossdressing ‘aunty’ played by Grahame Bond, who wore a boxing glove and football boots and regularly threatened to ‘rip yer bloody arms off’. It was unlike any other show on Australian television. The Norman Gunston Show featured a fictional talk show host played by Garry McDonald, who confused international celebrities with his extravagant Brylcreemed comb-over, shaving cuts and illfitting suits. Gunston’s seemingly naïve, yet pointed, questions neatly skewered his interviewees, leaving them agog or in fits of laughter. Both programs reflected an affectionate, but also sardonic take on Australian culture while providing a surreal commentary on the mainstays of commercial television, including soap operas such as Number 96 and The Sullivans, and late-night shows such as The Graham Kennedy Show and The Ernie Sigley Show.

Bruce Postle, Norman Gunston and Denise Drysdale at the Logie Awards presentation night, each with their Gold Logie, at the Southern Cross Hotel, Melbourne, 12 March 1976, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-148394048

Bruce Postle, Norman Gunston and Denise Drysdale at the Logie Awards presentation night, each with their Gold Logie, at the Southern Cross Hotel, Melbourne, 12 March 1976, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-148394048

Sport

While Australians loved television, they also loved their sport, and 1975 was a great year for sport. It had not yet become the entertainment business that would emerge in the 1980s, but the early signs were there. In winter, Australians were still very much obsessed with Australian Rules football and rugby league. Soccer had strong support among migrant communities and was just beginning to cross over into the mainstream, thanks mainly to the Socceroos having qualified for the 1974 FIFA World Cup. For Australian Rules fans, it was the Victorian Football League (VFL) which dominated. North Melbourne finally broke its jinx by winning the grand final in 1975 against Hawthorn, making it the last of the league’s 12 teams to win a VFL premiership.

In rugby league, it was the New South Wales Rugby League which attracted the biggest stars with its traditional 12-team Sydneybased competition. The 1975 grand final saw a clash between rivals St George and Eastern Suburbs. In a sign of the creeping commercialism entering the game, St George fullback Graeme Langlands sparked a controversy when he wore white boots, as opposed to the traditional black, as part of a sponsorship deal he had with Adidas. Such attention-seeking behaviour was unheard of in rugby league and, in a measure of karmic justice, St George was thrashed by Eastern Suburbs 30–0.

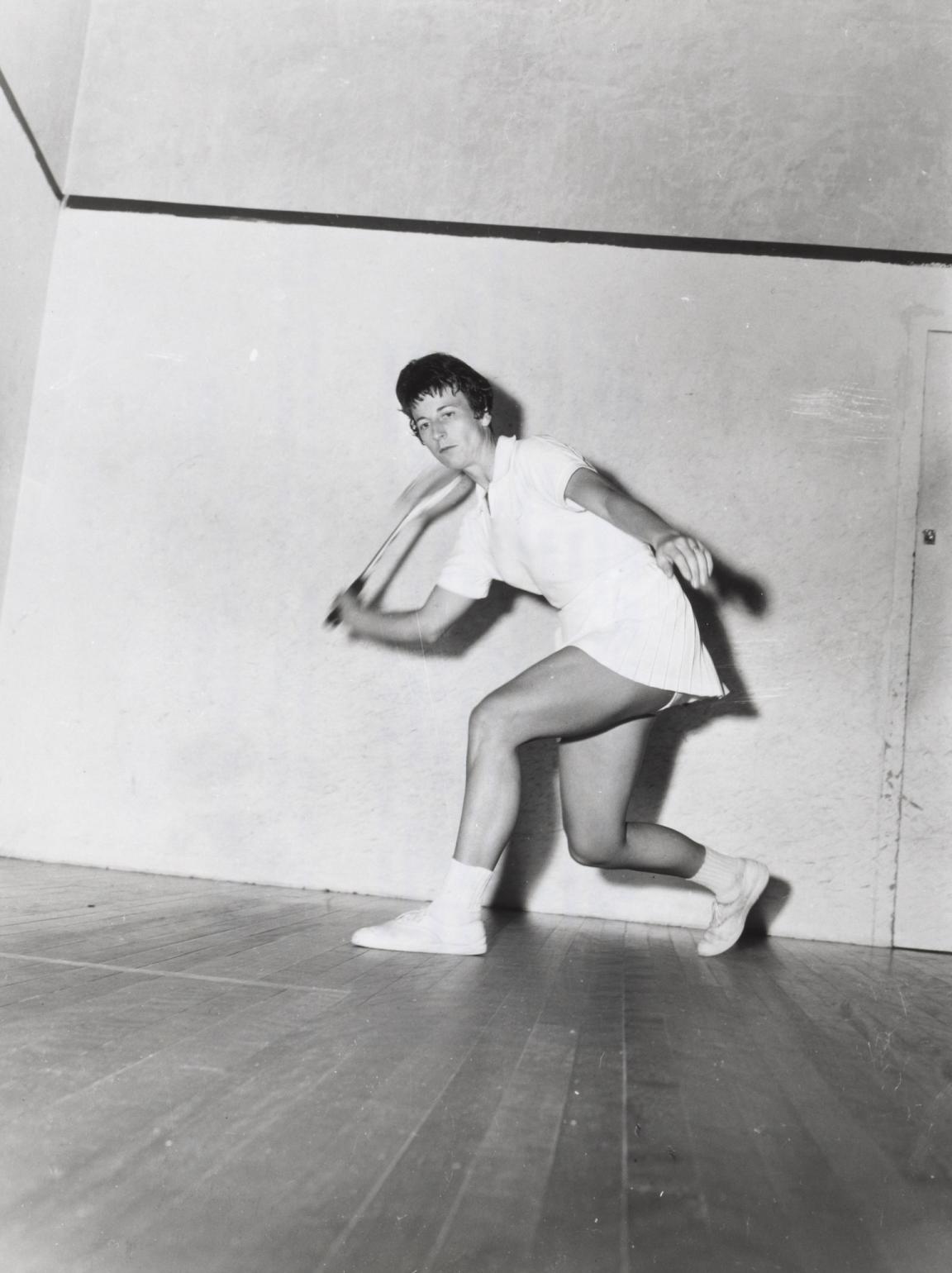

On the tennis court, Australians were dominating international competitions. Evonne Goolagong (Cawley), a Wiradjuri woman, won the 1975 Australian Open by defeating Martina Navratilova 6–3, 6–2 in the final. John Newcombe became the men’s champion in the same tournament when he overcame American champion Jimmy Connors 7–5, 3–6, 6–4, 7–6.

Australia hosted the charismatic West Indies cricket team for the summer. The series was notable for the destruction wrought by Australian fast bowlers Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson, both of whom could bowl at over 150 kilometres per hour. Australia won the series 5–1, but ‘the Windies’, as they were universally known, had learned the lesson of the power of fast bowling and would return in future series with a blistering bowling attack.

The success of the Windies’ tour attracted the attention of media magnate Kerry Packer. When the Australian Cricket Board rejected his 1976 bid for the broadcast rights, Packer responded by establishing the World Series Cricket competition a year later. After two seasons of parallel international competitions, a compromise was negotiated—and Packer achieved his goal of obtaining the broadcast rights for cricket. This was a major step towards the professionalisation and commercialisation of Australian sport. Competitions that had been parochial and suburban for decades began to be transformed into the major national sports businesses that we know today.

Heather McKay playing a forehand drive during a squash match in Canberra, 1972, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-137403541

Heather McKay playing a forehand drive during a squash match in Canberra, 1972, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-137403541

1975 at a glance

When we look back to 1975, it is tempting to view Australia through a haze of nostalgia. You can still hear classic ‘hits of the seventies’ on the radio, watch the iconic TV shows on YouTube and laugh at pictures of outrageous moustaches, white silk shirts and flared jeans. But is there more to this year than a dose of boomer nostalgia? Looking at the collections held by the Library reveals a much more complex story. 1975 was a year when Australia was in transition. Its economy was undergoing fundamental change, with increasing reliance on the mining sector. The flow of migrants coming to Australia had begun to shift from Europe to Asia. The White Australia policy, which had been slowly dismantled over the previous decade, was finally gone, replaced with a commitment to multiculturalism by both the Whitlam and Fraser governments. The women’s liberation movement had challenged many long-held assumptions about the roles of women in Australian society. The establishment of women’s refuges and no-fault divorce were important first steps in addressing deep injustices in Australian society. Our colonial legacy, and particularly the dispossession of Indigenous Australians, was now firmly on the political agenda. While the year ended with the dismissal of the Whitlam government, reforms would continue through the late seventies and into the eighties.

Change was not limited to politics and economics. Australian popular culture was also reinventing itself. By the mid-1970s there was an increasingly confident cohort of performers, writers, filmmakers, television producers and artists producing a distinctly Australian take on the world. The nation had begun to tell its own stories. The cultural cringe which had defined our attitude to the world in the 1950s and 1960s was beginning to fade. Australia was now a much prouder and more assertive nation. Skyhooks captured this new cultural confidence with their second hit album for 1975: Ego Is Not a Dirty Word. Like the band, Australia had begun to embrace its own distinct style and celebrate its place in the sun.

Visit us

Find our opening times, get directions, join a tour, or dine and shop with us.