Learn with the curators of the Treasures Gallery

In this recorded webinar, you will learn with the curatorial team behind the recently refreshed Treasures Gallery and hear some of their favourite stories behind the collections and services of the Library.

Members of the Exhibition team will discuss items from this diverse exhibition, on topics including our Asian Collection, the papers of pioneering female aviator Freda Thompson, and key moments from Australia’s democratic history. Guest expert, Kate Ross, will reflect on 30 years of “one of the biggest collections that people might not be aware of”: the Australian Web Archive. Curator Nicole Schwirtlich will offer further insights into the considerations taken by the Exhibitions team in selecting and displaying these precious items.

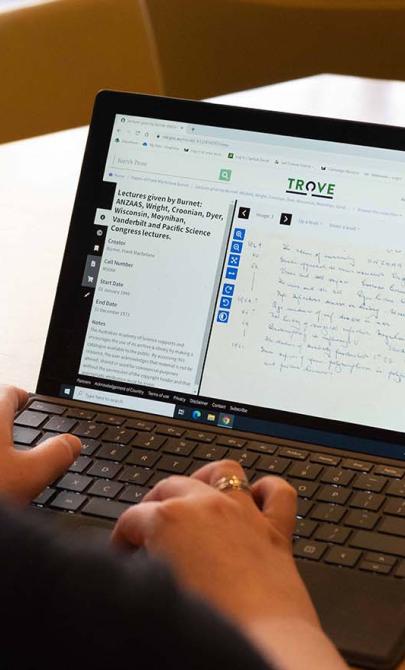

You will be invited to reflect on what it means to consider something a ‘treasure’, and have the opportunity to look closely at a range of objects from the collection. Website navigation is modelled throughout the video to help you learn to access digitised versions of these items. The session also includes the inspiring case study of the Lockhart Family’s collection of photographs and information around family history services to get you started on your family history research journey.

Follow your curiosity in the Treasures Gallery and decide for yourself, what makes a treasure?

Learn with the curators of the Treasures Gallery

Karlee Baker: Welcome, everybody. It's fantastic to have you here for Learn with the curators of the Treasures Gallery. Thank you for joining us today. My name is Karlee. I lead the Lifelong Learning programing here at the Library, and I'm joined in the gallery by Nicole Schwirtlich. How are you going, Nicole?

Nicole Schiwirtlich: I'm great. Thank you, Karlee.

Karlee Baker: Nicole is one of our head curators for this gallery refresh. And Nicole, we've got people joining us from all over Australia today. Every single state, which is lovely. Here at the National Library, we acknowledge the First Australians as the traditional owners and custodians of the land that we're really lucky to get to work on. We pay our respects to their elders and through them to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

We'd also like to acknowledge the Opalgate Foundation for their tremendous support of our Library's Lifelong Learning Initiative.

Now, the way that you will communicate with Nicole and I today is via the Q&A and the chat. So please go ahead and open up those boxes. If you don't see the Q&A down the bottom of your zoom panel, there's a small circle with three little dots that will give you some more options.

You can see that we have the wonderful Ben from our learning team, who's already started to drop in some information, as well as our community standards guidelines. We also have Kate Ross from the web archive, who is on hand to answer questions about the web archive.

So I hope that you've all got those opened up ready to communicate with us. Sharing your ideas, your contributions will really help guide our discussion today. And to get us started, I'd like you to think about your home and the vast quantity of items that you might have in your home that really help tell your story. So the Treasures Gallery is a fantastic way for us to showcase what the library does. We have around 11 million items, so the curators have done an incredible job of picking those representative items to help tell the stories.

Imagine you get to pick two books, two photographs, maybe a piece of clothing, maybe one sentimental object, maybe something related to your hobby. What would you choose?

What treasures would you choose that would reflect to people coming into your home who you are? What your story is?

We've got some fantastic ideas coming through. People are saying things like something that's valuable to them. Thank you Jude, your artwork. You see the beauty in that artwork and you want other people to see it. What a fantastic criteria for a treasure. Chris, thank you. Things that have sentimental or cultural or heritage value or maybe a family heirloom. Yeah. Things that tell a story, Mary. Things that culturally significant. So, Helen, I wonder what items you might have that also represent culture within your home. And the same within our collection here. Patricia. Your parents’ immigration documents and passports.

What a treasure. Fantastic. Oh, there are so many wonderful ideas coming through your call on there. Yeah, and also things that might hold value to you, but, you know, would be valuable to others, Bec, so you’re thinking sort of outside yourself there. Thank you.

Nicole and I will be jumping in and out of the gallery here: we'll have a look at Legal Deposit and the display there with Grace, we’ll join Karen for the Asian Collection and a very special map, we’ll look at the manuscripts collection. We'll look at some of the ways that we document, Democratic history here at the library. Nicole will do a fantastic presentation on Australian Life and a beautiful case study on family history. And then we'll finish up with a conversation on the couch with Nicole and Kate, all about the Australian Web Archive. Now we're going to meet Grace, in Legal Deposit.

Dr Grace Blakely-Carroll: Have you heard of legal deposit? Legal deposit is a program managed by the library and it's part of the Copyright Act. What it means is that a copy of everything published in Australia is collected by the National Library. So that might be, family history that you might produce, a community newsletter. It could be a published book by a major publishing house.

And it's the responsibility of the person who created that to send a copy to the National Library of Australia and also a copy to your local state library. If you're not in the ACT.

Through the legal deposit program, which is not curated, by that we mean it doesn't have somebody deciding what we collect because we collect everything. You could think of it that Australia decides. But through this program, we have a very rich record of Australian life and it's reflecting everything that is published, be it, a physical book or increasingly an electronic publication the Library collects digital publications largely through our NED program, our National eDeposit program. It's a program in which we've partnered with state libraries from across the country to ensure an electronic copy of a publication is available for readers at the State Library and also at the National Library. We have a digital first, philosophy in which for legal deposit, we would collect the digital, e-book version, in the first instance. And that's partly to do with the fact that our collection is growing all the time, both physically and digitally. And we're keeping, space for, important physical collections that aren't available electronically, by collecting the ebooks in the first instance.

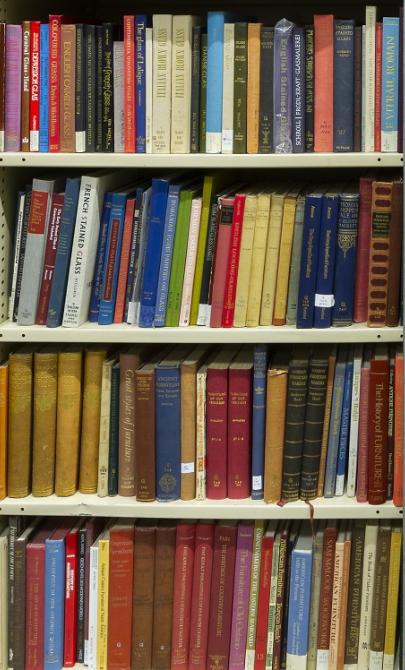

I like to think of legal deposit as a way that the Library serves as the nation's book collection. So it's almost like the nation's bookshelf. We have a copy of everything published in Australia. And behind me here we've got an example of an individual's bookshelf. This is a bookshelf that has been carved by the Australian poet Dorothea Mackellar. And she carved this when she was a teenager. She wasn't a professional woodworker. This was more of a hobby, and I can only imagine what inspired her to carve this bookshelf. But we do know that she loved books and she loved reading, so perhaps it was to house her personal collection of books.

These books here are a selection of the sorts of things that we imagine Dorothy might have had on her bookshelf. Now, you might have noticed that there's one title that's more recent that wasn't published in her lifetime, restless Dolly Maunder by Kate Grenville, which is a book that's inspired by the life of Kate Grenville's grandmother. The reason I've included it in the display is actually that Dorothea Mackellar appears as a character in that book.

I wanted to include this display to illustrate, an individual's collection, because, of course, the practice of collecting and looking after one's books or other treasured items is very personal. And it's quite different to what a national collecting institution does. Like the National Library, I know for me, I have my own personal collection of books that I store in a particular way that's special to me. And those titles have personal meaning.

So I wonder what might be on your bookshelf and how you might look after your collection? Is it a physical collection? Is it a digital collection? Perhaps it's not books, maybe photographs, or something else, but we hope that through seeing this display, you might think a little bit more about the value of that collection, what it means to you, and maybe even what it might mean to others?

Nicole Schwirtlich: So our intention behind this project was to create a gallery space that could be used as an introduction for visitors to what the National Library does. And the services that we provide. We also wanted to answer some common questions that we received from visitors, such as where are the books? Where do we store our vast collection? How do we build our collection? And how can you, the visitor, access our collection, both online and also from home? We also wanted to give a bit of insight into what we call the secret life of the National Library, and the work that we do to care for the collection and to build it.

And we've done that with the fabulous marketing team. We've created three videos on the intro wall to the gallery that show how a book will travel from the stacks to the reading room so you can access it, how material is digitised, and how our collection care team care for all the items.

Karlee Baker: Great. Thank you. Just heading into the into the chat. I agree, Chris, it is such a way to evoke curiosity, having that legal deposit display as one of the first things that you see. It's a surprise to a lot of us that this is one of the really important services of the library. We're going to head now into the Asian Collection, and we will meet curator Karen.

Dr Karen Schamberger: This book contains the illustrations of the Sixteen Arhats who were enlightened disciples of the Buddha. In this book the Arhats were drawn onto patra (leaves) which were then pasted onto paper and silk. The name of each Arhat is given in Sanskrit and transcribed into classical Chinese. The pages of this book are folded like an accordion, known as ‘sutra binding’, and covered using two timber boards.

These Arhats had attained Nivana and had broken free from the cycle of birth, death and rebirth or samsara. They are regarded as beings who have achieved a state of spiritual perfection and personal liberation. Unlike Boddhisattvas, who remained on earth to help others achieve enlightenment, Arhats took a vow . to remain in the world and protect the Dharma or Buddhist teachings until the arrival of the future Buddha, Maitreyat

The page I have chosen for display is that of Arhat Kanaka Bharadvaja. He is often shown holding a begging bowl or simply resting his hands, and is a symbol of compassion and detachment from materialism. His portrayal emphasizes the virtue of renunciation.

In ancient India, his father was a wealthy Brahmin who lived in the ancient city of River city. He was born holding a gold coin in each of his hands. A result of his good karma. Each time the coins were removed, new ones miraculously appeared to replace the old ones.

Bharadvaja grew up to be a kind and compassionate individual, and he generously donated his gold coins to the impoverished and the monks. His name, Kanaka, means gold. One day he traveled to Jetavana, where a Buddha dwelled in a grove, and he was so impressed with the Buddhist teachings that he eventually became the Buddha's disciple.

So Buddhism influenced Japanese woodblock prints from the 11th century AD onwards.

To make the prints, artists engrave different blocks made of cherry wood. One for each watercolor paint. The black outline was the first color to be printed onto the handmade paper from the paper Mulberry tree. Then subsequent wood blocks were carved and painted with different colors, and they were pressed onto the paper separately. During the eight hour period of 1600 to 1867, woodcuts were also produced for esthetic appreciation.

Scenes included theaters, neighborhoods, landscapes, and tea houses, as well as scenes from legend and folklore, often depicting supernatural beings.

This woodblock print by Tagawa Yoshimura is called Devil Dogs Being Judged in Hell by Emma-o, which was printed in 1891. Yama, the god of death, judgment and justice, is pictured here with a fierce expression, wearing a Chinese judge's cap and holding his mace of office. Yama originated in Buddhism, and he became popular in Japanese Buddhist belief, where he is also known as Miho.

The dogs in kimonos kneel as they are sentenced after death by the god, while others have already been sent to hell for what they did during their lives. And you can see that because they're already flying in the blue

The second woodblock print. The Cats’ Bathhouse dates to the Meiji era, 1868 to 1912, which saw Western influence increase in Japan. This included the change of red pigments used for these woodblock prints. By this time, reds became much more vivid and loud. The cats here are depicted in a public bathhouse or center, which have been a part of Japan's bathing culture for hundreds of years. Every neighborhood has one. And families visit them regularly. Males and females go to separate baths, and the children stay with the women. As you can see in this scene here, which has both adult cats and kittens, the story starts at the doorway at the bottom on the women's baths, and it moves through the entryway and pay station up to the cleaning area and then the public baths at the top.

This map of the city of canton is from the Library's London Missionary Society collection, which was purchased from the society in 1961. The majority of the 722 collection items were published between the mid 1800s and early 1900s, with a few dating back to the 17th century and some from the 1950s. Items provide insights into China's political, religious and cultural life from this important historical period.

From 1757, canton, which is now known as Guangzhou, was the sole port of entry for Western goods into China. By the late 18th century, the British Empire had accumulated a massive trade deficit with China, as that country had no interest in acquiring Western goods. And they only accepted silver as payment. The East India Company brought opium from its Indian plantations to China instead of silver, which resulted in a massive increase in opium addiction amongst the Chinese population.

And this led in turn to the First Opium War of 1839 to 42, and then the Second Opium War of 1856 to 60. An American missionary, cartographer, and diplomat, Daniel Vrooman, drew maps of Chinese cities that helped European powers better exploit the country. He was first posted to Canton in March 1852 by the American Board of Commissioners of Foreign Missions.

His interest in mapping Canton was limited by the closure of the old City to Westerners. So he used local informants and a convert. He trained in measurements to assist him while he drew his large scale plan of Canton, which was completed in 1855.

He continued to refine his drawings, and the Library's map of Canton dates to 1860. And it is one of the first maps made after foreigners were permitted access to the walled city, which is shown in pink.

You'll notice that this map has a number of creases. This is because it was folded and unfolded numerous times during its lifetime of use. It was then backed using linen fabric to make it stronger and easier to handle and fold for storage. Over time, more creases and folds appeared with constant use. Tension between the paper and linen can cause tears along fold lines, wrinkles, and even the two layers pulling apart. So the conservators here at the library hav stabilised the map so it doesn't deteriorate further, but it still retains evidence of its life history.

I also wanted to mention one last thing. There is a connection to Australia, because in 1878, Vrooman was made superintendent over a mission to the Chinese in Victoria, many of whom had traveled from their home villages around Canton. While Vrooman retired from his Australian post in 1881 and returned to the USA. His story and the map are a reminder of how the Library's Asian collections help connect Australia to the world.

This tactile or braille map of Australia was published in Germany in 1889. Tactile maps used raised and depressed surfaces, as well as a variety of textures to indicate geographic features and boundaries. Prior to the 1830s, tactile maps were usually custom made for a few individuals who were visually impaired.

In the 1830s however Martin Kunz, director of the Illzach bei Mülhausen Institute for the Blind in Germany, developed an efficient method of printing tactile maps by pressing cardboard between an elevated and a depressed mound. Kunz drew upon a method that had been developed by the Guldberg in Denmark, which he was able to produce at a larger scale.

These maps were the first efficient paper relief maps for use in schools, and a copy of which each pupil in the class could be given. These maps aroused great interest in other countries after being exhibited at the first congress for teachers of the blind. This map of Australia and its surrounds incorporates contours indicating details such as mountain ranges, rivers and is embossed with Braille script.

It also includes handwritten place names, often in German. However, there is a mistake. The equator is incorrectly shown passing through Papua New Guinea at approximately latitude seven degrees south of the actual equator.

Karlee Baker: That's a great opportunity for us to think about. A couple of questions that we've got in the Q&A around, collecting priorities. So, Nicole, could you tell us a little bit about the Asian collection and some of those collecting priorities we have here?

Nicole Schwirtlich: Yeah, sure. We have photographs, manuscript collections, maps, as you've seen and so on. Regarding Asian collecting, we do have international collections. They are a small part of our collection. And the reason we do that is to situate Australia within our global and regional context. So international collecting priorities include like Indonesia, China, East Asia more broadly and the Pacific.

Karlee Baker: Thanks, Nicole. We’ll now head into our manuscripts collections display. So thinking about some of those treasures that you have at home. And also harking back to a fantastic comment in here from Lauren around surprising items that we might find that tell us a wider story, about particularly, women who might be, working or having hobbies in surprising areas. So let's head in and hear from Karen, oops, from Grace this time.

Dr Grace Blakely-Carroll: The Library collects the personal and professional papers of many Australians. It's a curated collection, which means that expert staff identify individuals whose papers we wish to acquire. They may be living or they may be deceased. And by papers, I'm referring to letters, diaries, information about that individual's life, usually their professional life and the things that they have achieved in their lifetime that might be of relevance for the future.

We would also collect material related to their personal circumstances, perhaps their childhood, family photographs, things like that. These documentary resources help us tell a rich story about Australian life and Australians in the world.

One of my favorite collections of manuscripts held by the library is the papers of Freda Thompson. And we have a display here in the Treasures Gallery of material from her papers.

Freda Thompson was a pioneering Australian aviator. She was the first woman to fly solo from England to Australia, and she did so in her aeroplane. It was a gypsy moth which she named Christopher Robin. Freda was a real go-getter in her time and didn't let things hold her back, and that story is really held and preserved for posterity in her papers. There was a time where she was the only woman in the Commonwealth to hold the qualification of a pilot instructor. That was in the 1930s. It's sort of amazing when we think about that today and the sorts of things that, women do today, which for somebody afraid is time would have, perhaps seemed out of reach through being trained as a pilot instructor and also through her work as a pilot and, her achievements, Freda had to have a really in-depth understanding of the mechanics of a plane.

So that's why some of the material we have in in this display relates to that. We've included her plane manual, which she would have had to carry with her at all times, and she also would have carried a separate manual that relates to the engine of the plane. So she would have to understand how to do all of the maintenance herself, because her journeys would have required many stops to refuel and to check that everything was just so as she flew solo. Now, flying at that time was very different to flying today. And some objects we have in the collection of her manuscripts help us unpack that. Set in the 1930s and 40s when she was flying, planes didn't look like they do now. The engines were very noisy and there was very little by way of protection for the pilot flying the plane. So they wore caps and they also had special goggles, and some of them even had night vision lenses. And we can see that technology, in these objects that we have behind me here. So we've got her pilot's cap, we've got some goggles and some lenses. It's unlikely that she wore these on her, famous flight in the 1930s, as they do appear to date from the 1940s. Based on some research that our conservation team has done here. But nonetheless, they are the sorts of things that she would have, definitely worn during her flying career.

We can also see a map which she would have carried with her while she was flying. It's quite sturdy, as it would have had to really withstand the elements and the maps in nautical miles as, aviation maps. It's a strip chart, so she would have been able to, roll through the chart while she was flying. Some pilots would have attached it to a board on their knee so that they could keep in charge of the plane whilst also staying across, the map and making sure that they were going to the right places.

So with this collection, not only do we learn about Freda and her story, we've got some information about her life, some photos of her, but we also learn about the technology at the time and what it would have been like to be a pilot and specifically a female pilot at a time where it wasn't nearly as common as it is today.

So that's an example from our manuscript collection of a collection related to an individual. And it's actually part of a larger, series of related collections themed around aviation. And the library's undertaking a big project to digitize our aviation manuscripts. So if you head on to trove, you can find much of this material online, including freighters, papers.

In addition to collecting papers of individuals, our manuscripts collection also includes the papers of organizations. An example here behind me, features material from the Australian Lebanese Historical Society. A theme in the display is small businesses because many Lebanese Australians whose material is included in this collection were small business people. So that's why we have a shopping bag and some other, ephemera and material related to those occupations and the contribution that these individuals have made to Australian life.

So some of the items in the manuscripts collection, more well-known than others, or perhaps have had more impact on Australian life and the way we see ourselves as Australians and also our place in the world. And one example is a copy of the Gallipoli letter by Sir Keith Arthur Murdoch that we have in his papers here. Now, that letter was written during the First World War, and it's a letter to the then Prime Minister, Andrew Fisher.

And Murdoch is writing about what was happening, on the shores of Gallipoli in modern day Turkey, where the Australians were, were fighting in the war with the Kiwi or New Zealand, mates as well. And some of the difficult scenes that that were unfolding during the war. So for many Australians, Anzac Day and commemorations around Anzac Day, are something that we learn about at school and it's something we commemorate each year.

Some historians, argue that this letter, was very influential in shaping the mythology around the ANZACs and also, concepts of Australian identity, mateship, masculinity and that those ideas are still, being unpacked and explored in Australian society today. So this letter, which is, typed, it's quite a humble looking document, is an example of the sorts of things we have in the collection that tell us about a particular time in Australian history, but also capture those moments for the future.

Our manuscripts collection is rich and diverse and one of the favorite stories I like to tell about the collection relates to the classic children's book Where Is the Green Sheep? It was first published in 2004. I was delighted to learn that we have the original illustrations for that book as well as the drafts of the manuscript and related material, and the collection is broken up in two different manuscripts collections. And that's because we have the papers of Judy Horacek the illustrator of that book, as well as the papers of Mem Fox, who wrote the text in the display behind me.

Here you can see one of the illustrations. It's the bed sheet reading a bedtime story. I wonder what that is? And we also have the typed first draft by Mem Fox, as well as a first edition of the book elsewhere in the papers of Mem Fox, we find copies of emails between Judy and Mem where they're discussing, bringing this story to life.

And of course, at the time, they couldn't have possibly known how many children and grown ups were to be touched by this wonderful story, a real treasure for the nation. And one of the many books, whose story we preserve through our collecting efforts at the National Library.

Karlee Baker: I love the way that Grace describes the go getter nature of Freda Thompson. We've got a fantastic question, Nicole. From Dee around how, digital items, looking forward, preserving

Nicole Schwirtlich: And you'll see later in the webinar, we have some examples which are digital inherently, and the Gallipoli letter would be an example of a physical item that we have digitised. It's so it can be accessed more widely, but also, for preservation reasons as well.

And then even later on in the webinar, there'll be a segment on the Australian Web Archive. And, and you'll see how we've been able to incorporate that into the gallery space using a projector, which was, a really exciting feature. We were able to include with the refresh.

Karlee Baker: Okay. Thanks, Nicole. Thinking of go getters and change makers, let's head in with Guy to look at some of those items that we have around our democratic history.

Dr Guy Hansen: So Federation has a few significant dates. Of course you have, the inauguration of, of, the Commonwealth. But this particular moment, it is the 9th of May, 1901, with the opening of the first federal parliament in Melbourne.

The painting here is Tom Roberts’ oil sketch of the opening of the first Parliament, in the Exhibition Building in Melbourne. So this was the moment that Australia, achieved nationhood and the opening of the Parliament. Of course, the parliament was in Melbourne up until 1927, when then moved to Canberra. So this is a really important moment, a milestone moment in the history of Australian politics.

So Tom Roberts was commissioned to do a painting marking this historical event. And the big painting can be seen, up at Parliament House today. But I really like this oil sketch because it's so vibrant and so alive. You can see the light, you can see the energy of the figures in the in the building. So I think it's a fantastic memento document relating to the Federation of Australia. While it's an oil sketch, you can still make out some of the details. You can see the Duke of Cornwall and York, addressing the gathered, VIPs of the day.

So, obviously Australia is a constitutional monarchy. And, we were recognizing, of course, the royal family as part of our, constitutional set up. So it's a it's a great painting. Beautiful light, beautiful color, beautiful movement and a really important moment in Australian history.

So the library collects all sorts of material which documents the history of Australian democracy. One type of material which we do like to collect is election ephemera. We have pamphlets and leaflets and posters and badges which go right back to 1901.

The material you can see behind me is, from the 1949 election, which is a really interesting election because Ben Chifley was prime minister. Labor had been in the second half of World War Two, had been in power in Australia. And, it was at this election, after the war, when postwar reconstruction was underway, that RG Menzies was able to run a campaign with the newly created Liberal Party, and Menzies was elected prime minister and would remain prime minister for a very long time.

So you had two great prime ministers marked in this election. The end of Ben Chifley’s term as prime minister and the beginning of RG Menzies’ term as prime minister.

Okay. So, Faith Bandler, who you can see in this painting, was descended from Pacific Islander people who'd been brought to Australia to work as indentured laborers. This was a practice which was sometimes referred to as Blackbirding.

She was one of the main campaigners in the 1967 referendum. The referendum made provision for a change in the constitution, which would allow the Commonwealth government to count indigenous people in Australia and also to make laws. So this was a really big change, in the Australian federation. And it allowed really important changes later on, such as things like land rights legislation.

So Faith Bandler was one of the main activists who campaigned for this change in in the constitution. And as we know, changing the Constitution is extremely hard work. You need a double majority, both a majority of the citizens of Australia and also a majority of the states in Australia.

And Faith Bandler’s work was really important in getting that constitutional change through.

So the National Library collects a range of material relating to important political leaders in Australia that includes politicians, members of parliament, but also activists who campaign for change in Australian society.

So the 1967 referendum campaign generated a range of political ephemera. And you can see here a poster encouraging people to vote. Yes. These are really important things to keep, because the evidence of how political change was achieved in Australia.

Karlee Baker: So, Nicole, we've got some fantastic questions here. Dee has, well, Dee's commented on that connection that they feel with, Where Is the Green Sheep?, as I do as well Dee. That’s Lovely. How does that make you feel Nicole?

Nicole Schwirtlich: Well, the National Library, as I said, we collect material about Australia and the Australian people. And when we're curating exhibitions, that's exactly what we want to reflect. And we want visitors to come in to the gallery and feel that they can see themselves and their experiences in the display. So saying comments like that makes it feel like, yes, we've done our job.

Karlee Baker: Fantastic. And Belinda asks, well, how often are you going to do this huge job that you've just done? How often will the treasures gallery be refreshed?

Nicole Schwirtlich: Yes, this was quite a big refresh. But we do changeovers intermittently, depending on when some items need to come off display. So it's for preservation reasons. But I think big refreshes like this not as often.

Karlee Baker: All right, Nicole, we're going to send you back into the gallery now to tell us about some of those items that you've chosen to represent Australian life. And then we'll move into a case study around family history.

Nicole Schwirtlich: The library holds the world's largest collection of documentary material about Australia and the Australian people. Our collection preserves a variety of perspectives on Australian life from across time and in many formats. When curating this photographic display. We organised material into broad themes such as recreation, community, work, life and sport. Photos were also paired up using a then and now structure to explore how Australian life has changed or stayed the same over time.

For example, in 1972, the Australian Information Service took this photo of the first meeting held by the Fiji South Australia Association in Adelaide. At the meeting, members prepared and drank kava, a practice which is culturally significant in Fiji and throughout the Pacific. 50 years later, the library commissioned Leigh Hanningham to photograph Fiji Day celebrations held in Melbourne.

This photo from the collection shows members of the community preparing kava for the welcoming ceremony.

So this is a photo of Agnes Lockhart and Norman Hackett on their wedding day in 1929. They got married at a Presbyterian church in Piangil Victoria. But Agnes’ family was actually from Goodnight, which is just across the border in New South Wales over the Murray River. Her wedding veil was purchased in Melbourne, where she'd been previously living while working at the Royal Melbourne Hospital as a nurse. And her veil was worn by her sisters, her daughters, her granddaughters and members of the Goodnight community.

So over the course of 64 years, 27 brides wore this veil. Agnes’ one condition when brides borrowed her wedding veil was that she'd receive a photo of the bridal couple. And that's how the Lockhart collection came to be. And it was donated to the National Library in 2005 by her daughters, Jenny and Rosemary.

Karlee Baker: Oh, what a gorgeous story. Can you tell us a little bit more about family history?

Nicole Schwirtlich: Yes. So whether you're an experienced family historian or you're just starting on your research journey, the National Library has a wealth of resources at your disposal. If you're just starting out, I'd highly recommend checking out our Family History Research Guide that's available on our website.

It shares some great tips and tricks with how you can approach your research, and also how you can structure it too. And on your journey, if you have any inquiries, please reach out to our Ask a Librarian service.

Karlee Baker: Yeah, fantastic. We will now send you back to the couch. You can have a bit of a relax and a discussion with the fabulous Kate about the web archive.

Nicole Schwirtlich: The Wiggles, a children's music group, was formed in 1991 by Anthony Field, Murray Cook, Greg Page, Jeff Fat and Phillip Wilcher, who met while studying early childhood education at Macquarie University in Sydney. In 1997, the first official Wiggles website was captured by the Australian Web Archive. You can see how this beloved Australian band has grown over the years by browsing their website over time on trove.

But what exactly is the web archive?

Kate Ross: Yeah, the Australian Web Archive is probably one of the biggest collections that people might not be aware of. I think it probably isn't as well known as some of the other things that the National Library has collected. But we have the oldest web archive in the world. It began in 1996, which means it's our 30th birthday next year, which is really incredible.

And I'm absolutely mind blown by our predecessors here and their foresight in starting to work out how to collect this crazy thing that was the internet. So yeah, I love that you can see that people were working out like what the web was and what it was for, and what websites were. And yes, I guess if you look at something like The Wiggles website. Yes, that's one website, right? And I love that they created a website in 1997. I think they were pretty on the on the ball. That same website, that same URL has been there ever since. And it's just been has evolved at the time with the band and yes, with, you know, Australian society. Really?

I guess if you can think about it, it's I think we consider it sort of the largest, for sure. And, possibly the most meaningful publishing platform, in Australia. And that's an important thing that we collect. Obviously, Australian publications. So where we're at now is that we, I think it's something like on average 15 files. So whether that's a little HTML file or a PDF or a image file, 15 files are collected into the Australian Web Archive every second.

So while we've been talking…

Nicole Schwirtlich: It's grown!

Kate Ross: Yeah, but we've collected some things, that are live right now. And yeah, it's, we're very excited that, just in time for the 30th birthday, we this year, we cracked. We went over a petabyte of data, which is, what we've collected and are storing. As you can imagine, that's a large piece of work work to store that. But even more significantly, I think, is to preserve it. So just like, other print, items that we've, we've collected over the years, we've got to preserve them. And make sure they're still, they're not falling apart and they're going to still be readable in the future. The same thing is true for this petabyte of data.

We've got to somehow work out how to keep it accessible and how those files can talk to each other so that we can still look at them like a real website, hundreds of years into the future or forever.

Nicole Schwirtlich: So is it everything with a .au domain that's harvested?

Kate Ross: So I think as you might be able to imagine trying to find Australian material so things written by Australians and that Australia for Australians it's really difficult because the internet is a really global thing.

Nicole Schwirtlich: Yes well it transcends borders.

Kate Ross: Yes. Right. Yeah. So one way we do it is to collect anything that has in the URL the .au at the end. Yes. That's one way we can identify Australian material. And so we actually do to really major harvest of every page on the internet that has the, where you and we do that twice a year, which is wonderful. And then to sort of supplement that, we also collect, anything that has the .gov.au

So to get all the government, material, it's really important that we keep a record of all the federal and state and local government websites as best we can. And some of those websites are absolutely massive. So we collect those four times a year. And we always will time those around things like elections or changes of government as well.

And then, it's hard to quite describe, but there is a very, very large and vast amount of material that is Australian online that doesn't have a .au websites of your favourite volunteer organisation or author it might just have a .org or a .com, but be totally like an Australian site.

So the way that we do that is we use humans to find the old, the old fashioned curatorial route. Right? So we have wonderful colleagues, at the National Library of Australia and curators who research and try to find websites about literally anything Australian. But we also have had a really long standing, collaboration with organisations all around Australia.

So we have some fabulous colleagues in, all the state and territory libraries, and other organisations who also find, material that's, relevant to their state and collect it into the Australian Web Archive.

Nicole Schwirtlich: And you're all just working together to, like, fill those gaps.

Kate Ross: That's right. Yeah. And we do we do really try as well to work together when there's a major event. So something big happens. Just like the Olympics are like. Yeah. Yeah. Right. When we've got, we've been doing the Olympics together for a long time. But also, elections or honestly other, sometimes really, sad events, things that are really important to the country. We do try to get in there and collect. Yes information. Because I think it's, it's easy to, not fully appreciate just how ephemeral the internet is.

People can change the content and the information on a website whenever they want. So, yeah, it's, when things happen, we want to try and get that information while it's happening. So that can be very, very in the moment. Yes. Collecting.

Nicole Schwirtlich: So the Australian Web Archive is obviously a hugely significant archive of Australian digital culture and history online and that's why it's on the Unesco Australian Memory of the World Register. Right?

Kate Ross: Yeah. That's so cool. Right. It's right up there on it with the Endeavor Journal and things. I think it's, it's really special that having this incredible resource of the oldest web web archive, that that's been recognized as just as valuable a historical artifact, as all sorts of older things and print material that I think we're, we're more we would associate more with-

Nicole Schwirtlich: Oh with being a treasure?

Kate Ross: That's right. The other thing that's, I think, really great to point out here is, that we've also, since the beginning of this work, I think by necessity, but also been very involved working with the international web archiving community. It’s a really effective and, collaborative group. So there's national libraries from all over the world represented in that group. Also, the Internet Archive, who run the Wayback Machine, people might, you know, work really closely together to kind of develop tools and, and problem solving ways to capture this material as it continues to change. And evolve. It's surprisingly difficult to collect the internet. I don't know if people would appreciate that. It sort of seems like it would be easy, I think, but it's complicated and technical. So we have some very brilliant, international, open source communities working, working on trying to solve those challenges.

Nicole Schwirtlich: If visitors are able to come to the National Library, you can see a selection of Wiggles websites that we've curated for the Treasures display. But if a visitor wanted to do a deeper dive into that collection, how would they access the web archive?

Kate Ross: Yeah, thanks for asking. We're so lucky in Australia. I think it's relatively unique. Only a few countries make, like us get to make their entire web archive. So we make the whole Australian web archive freely available-

Nicole Schwirtlich: Oh, amazing.

Kate Ross: To anyone, wherever they are, through trove. So trove, the National Discovery Service, is a website that you can Google and find, or you can find it through the National Library's website. And if you go to trove, there's a big search bar at the top. And if you type in, a keyword or a URL that you're interested in, the trick is you've got to make sure that you select websites from the drop-down list. Yeah, it's a little bit of a trick. It's the only category that you get that sort of by itself. Everything else you can search across formats. But we realized that if we put the web archive in there, it would absolutely swamp everything else that no one would ever find a book again. So we had to keep it to itself.

So yeah, I love hearing about how people are researching the Australian Web Archive and using it, fits all sorts of wonderful reasons. But also so from research and things, but also, just to check out your local information, check, see if you have favourite band or, from the nineties, or, I don't know, your volleyball club or your school is in there. Certainly, my life, my nostalgia was lived online I guess so, yeah. It's, I think for, for that generation, it's a really phenomenal resource.

Nicole Schwirtlich: Absolutely.

Kate Ross: Thank you.

Karlee Baker: I just love hearing about the significance and the enormity of the archive, Nicole!

Nicole Schwirtlich: I can't even fathom it. Like so big, huge.

Karlee Baker: And I think that's something that's coming up in the chat is this concept of access. And I've, I've tried to reflect that in some of the screenshots that you've seen throughout the presentations, the, the range of ways that you can access this material, because that's, that's one of our, our key reasons for being.

Nicole Schwirtlich: It’s why we do what we do, right?

Karlee Baker: We want to make sure that you can browse, that you can access, you can research. So if anything's come up for you today that you think, oh, I'd like a bit more help with finding out more about that. Like Nicole says, the Ask a Librarian service is fantastic.

And it's wonderful to see that some of some of the presentations have answer those questions around collecting in the digital age. So absolutely, all of those emails, all of those photographs that we collect that are telling our story, if when we become famous, if we would then to have our papers, taken in and looked after by the NLA (National Library of Australia) I wonder what that will look like?

All right. We will say goodbye now. Thank you very much, everybody. It was just fantastic to have your contributions and your questions today. And we hope to see you at another Lifelong Learning session soon. Goodbye.

About the Treasures Gallery

The Treasures Gallery is where you can find highlights from our physical and digital collection. In the Gallery you will find answers to popular questions, such as: ‘where are the books?’ and ‘what is Trove?’.