Human life in a wider ecosystem: Judith Wright and environmental action

In 2023, I was a Fellow at the Australian National University (ANU) in the Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs. Before arriving, I was assigned accommodation at Judith Wright Court in Acton, and this would become a serendipitous prompt to read the lifework of one of Australia’s most beloved poets. I knew Wright’s poetry a little but it was very much the established canon that I knew. In delving into her poetry further, I came across the poem ‘To a Child’, first published in the The Bulletin in 1950:

When I was a child I saw

a burning bird in a tree.

I see became I am,

I am became I see.

Though never cited as especially important, I think it beautifully signals Wright’s environmental thinking: on seeing the excesses of economic production in our contemporary world; on how that seeing can transform how we live; and on how living differently can allow us to see and safeguard a wider world.

Soon after arriving at ANU, I found myself frequently at the National Library falling down the rabbit-hole of Judith Wright’s work. What I initially found in the archives was a story that I could already see was vital for our age: it’s a story of climate action; a story of environmental campaigning; a story of heroism; a story of struggle and despair; and ultimately a defiant story of stoicism, responsibility and hope.

After returning home to Ireland, I applied for a National Library Fellowship in 2024 for a project focused on Wright’s environmental writing. I was so grateful to receive one, and returned to Canberra for a 12-week fellowship stay in May 2025.

Prof. John Morrissey, 2025 National Library of Australia Stokes Fellow

Prof. John Morrissey, 2025 National Library of Australia Stokes Fellow

Stokes Fellowship, 2025

My 12 weeks at the National Library was a joyous time, immersed in Judith Wright’s vision for a greater custodianship of the Earth. Over the 12 weeks, I went through 104 boxes of files on Wright and connected colleagues and friends (including Len Webb, Anne Edgeworth, Nugget Coombs and others) in the Library’s special collections. It was exhaustive but always worthwhile!

My fellowship was focused on joining the dots on Wright’s vision of human life in a wider ecosystem. I was seeking to capture the wider canon of Wright’s work through the lens of human geography and political ecology. In this endeavour I began uncovering how her work envisaged the then emerging trajectory of environmental crises, and how it considered the key challenge of communicating a pathway to a more ecologically responsible world.

Until her death in 2000, Wright worked tirelessly in disseminating what she called “a new kind of understanding” of humankind, in an ecosystem of “living processes and interdependences”. She communicated this holistic understanding of the Earth in art, education, activism and government policy, in academic circles and in the media – all in an effort to transform how we see and live in the world.

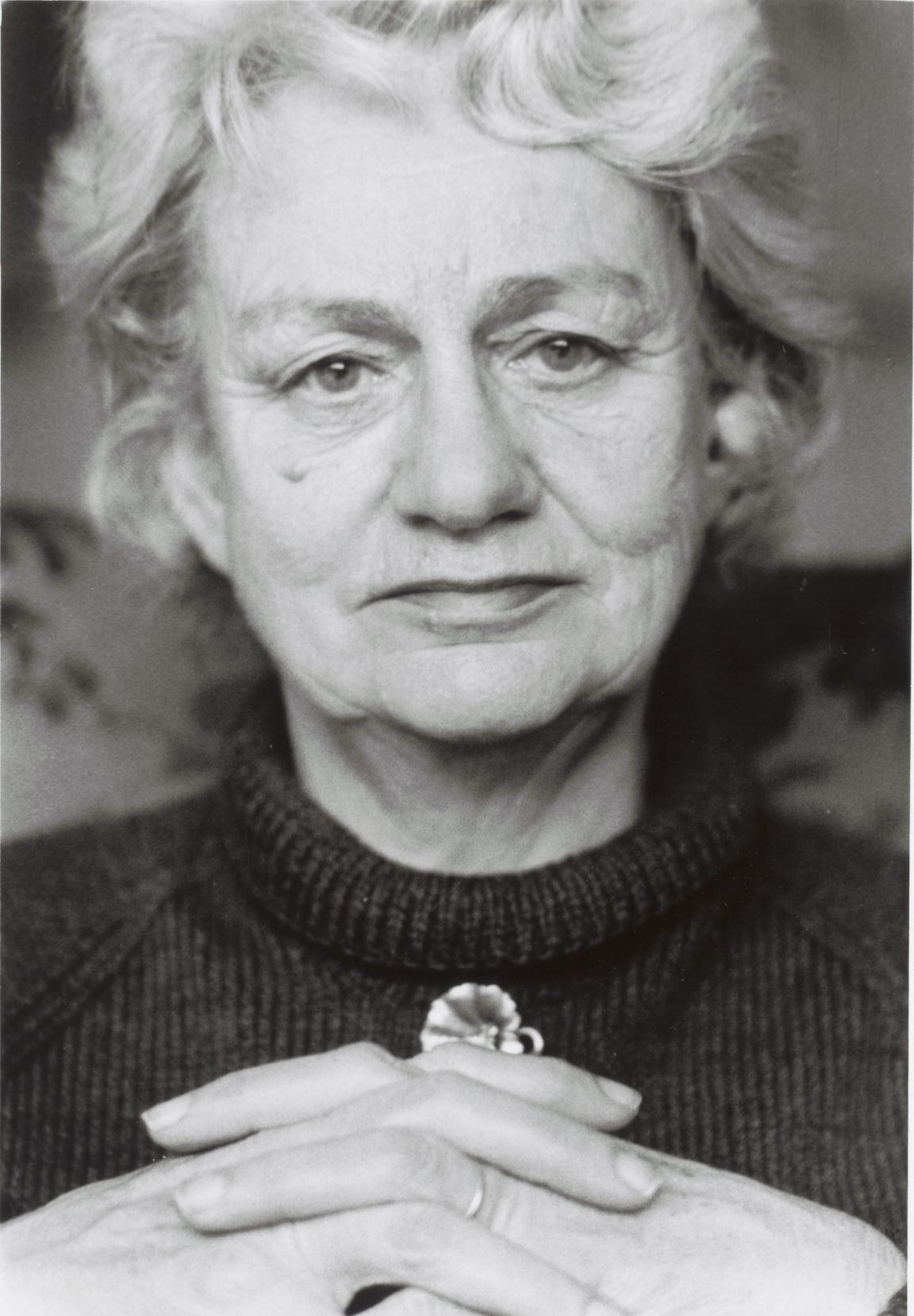

Jacqueline Mitelman, Portrait of Judith Wright, 1988, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136372491

Jacqueline Mitelman, Portrait of Judith Wright, 1988, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136372491

Wright’s environmental vision: 3 key themes

Wright’s inspiring environmental vision for the planet is recorded across a wide range of archives in the National Library. To give you a sense of her vision, I want to sketch here 3 key themes which emerge from her writing.

The first theme is ‘Human life in a wider ecosystem’. In Wright’s vision for human-environment relations, a repeated theorising advances an understanding of humankind’s position in a wider ecosystem, as part of a ‘deep ecology’ understanding of the Earth. Her ‘deep ecology’ equates in many ways to a critical political ecology perspective in seeing humankind in a highly politicised and interconnected planet. Wright felt profoundly a sense of being in a more-than-human world: she felt a “whole human reality”, a deep “respect for all things living”, and was haunted by the urgent environmental crises being ignored.

The second theme is ‘Safeguarding the future of the planet’. Wright wrote that humanity’s biggest task lay in “learning how to manage and look after the lonely little planet that is our only home”. She identified the ‘biosphere’ as an essential concept in thinking and acting environmentally, advocating the need for a more responsible management of the earth involving a new way of living and governing to transform the destructive economic productions of unregulated capitalism. For this vital challenge, Wright looked to “the future of the whole of the biosphere” in arguing for a necessary behavioural change in the present, and one that couldn’t be avoided by a technological fix: “we trust science to solve all”, but “our core challenge for the future” is a “transformation in ourselves”.

The third theme is ‘Communicating climate action’. A key global challenge today is the effective communication of planetary emergency and the urgency of climate action. In Wright’s correspondences and writings is an early incisive awareness of this pivotal communication task. Her environmental writing and activism divulge a sustained enterprise to convince governments, industry and citizens alike to alter excessive and individualistic modes of economic production and consumption. And despite the frequent despair evident in Wright’s papers, she stoically never stopped in her efforts to communicate emergency, necessary solidarity and everyday action. She ultimately refused to be a ‘passivist’.

Box of Judith Wright manuscript material in the Special Collections Reading Room

Box of Judith Wright manuscript material in the Special Collections Reading Room

Wright’s stoic vision for a world often in despair

Wright’s sense of not being simply in a human world was acute, and she had a fatal sensibility of the interplay between ecology and late modern capitalism. She wrote presciently about human-environment relations for our contemporary age, and on industrial-wrought climate change, in particular. Her greatest hope for humanity was to find a pathway to a more sustainable and ecologically responsible world.

Just like us all, however, she faced intense and prolonged periods of despair in the midst of this hope, and I think we need to historicise despair too – it will help us to remain stoic and determined in the face of seemingly overwhelming odds, impoverished leadership and powerful vested interests.

Australian News and Info. Bureau, Portrait of Judith Wright, c.1940, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136839298

Australian News and Info. Bureau, Portrait of Judith Wright, c.1940, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136839298

Showcasing the past to give hope for the future

The endgame for the work of my National Library Fellowship is a book that presents how Judith Wright envisioned a transformative custodianship of the Earth. Its focus will be on how she became critically informed of the overlapping threats to the planet’s biosphere, and how she endeavoured to enact a reprogramming of how we see, live and govern. In the book, I want to elevate her committed public scholarship and activism in saving the Great Barrier Reef, anti-mining campaigns, anti-woodchipping campaigns, industry pollution campaigns, defeating Concorde, household waste campaigns, biodiversity campaigns, campaigns against deforestation, supporting First Nations land rights, and so much more. These stories are all there in the Library’s archives, and my goal is to showcase them as inspiring exemplars of past environmental activism that give much needed hope to contemporary campaigns.

Knowledge, public scholarship and informed citizenship

Judith Wright’s archives form just a part of the wonderfully rich repository of knowledge at the Library. It is a joyous place to do research, and I will always be thankful for the support I received. There is a soaring sense of public scholarship alive and well in the Library, and that couldn’t be more important today.

Public intellectual institutions like the Library are vital and mirror the best of humanity – they stand for knowledge, they stand for community, and they stand for informed citizenship. I wish the Library all the best in that continued mission towards a better world.