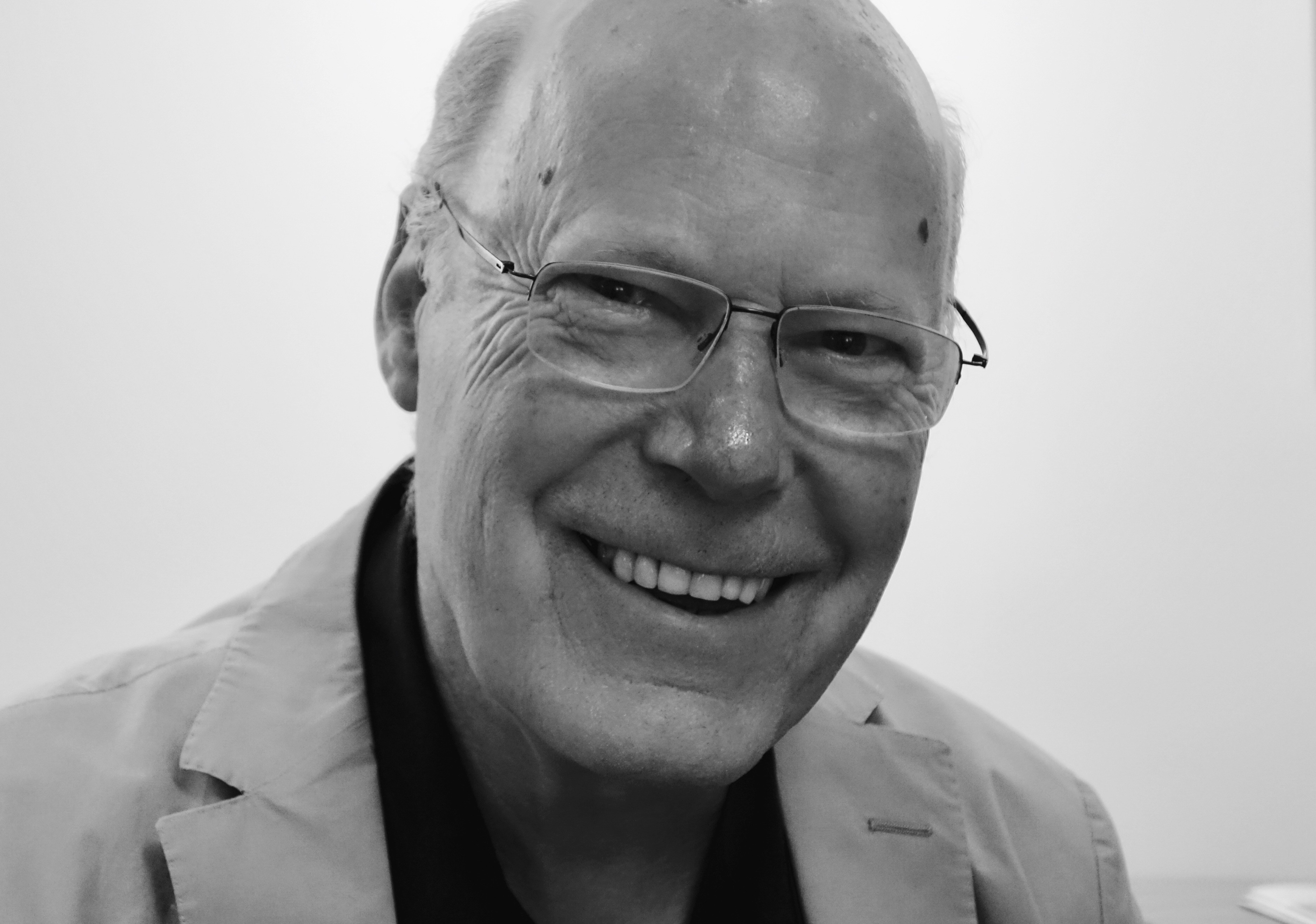

Jim Sharman in conversation with Hannah de Feyter

Excerpts from a remarkable collection of visual diaries created by Jim between 1960 and 2000 were on display, invoking memories, reflections, and inviting Jim’s thoughts on his legacy and the future of the arts.

Following the conversation, there was a screening of the documentary Strange Journey: The story of Rocky Horror. Made by Richard O'Brien's son Linus O'Brien, this documentary enjoys intimate access to its creator Richard O'Brien and other major players such as Tim Curry, Susan Sarandon and Lou Adler. The documentary explores what makes the play and film so singular: its groundbreaking and transgressive themes, iconic performances and epic songs that took over popular culture.

Jim Sharman in conversation with Hannah de Feyter

Conor McCarthy: Good evening everyone. Welcome to the National Library of Australia. My name is Connor McCarthy. I'm Director of Philanthropy here at the Library. Thank you all for joining us for tonight's event. And before we commence, could I remind everyone to ensure that your mobile devices are switched off? Thank you so much.

To begin this evening, I'd like to acknowledge that we're meeting on Ngunnawal and Ngambri land. I want to pay respects to elders past and present, and to extend that respect to all First Nations people joining us here this evening.

We're gathered here tonight to celebrate the remarkable work of Jim Sharman AO, a legend of Australian stage and screen. Jim has received many awards for his work as a writer and director for the theatre and cinema. He has over 80 productions to his name from experimental theatre through Shakespeare, from musicals to opera, and from 'The Rocky Horror Picture Show' to his collaboration with Patrick White.

We're very privileged to have Jim here with us this evening. Tonight's event is presented in partnership with the National Film and Sound Archive, so we're also delighted to be joined by the National Film and Sound Archive's (NFSA's) Hannah de Feyter. Hannah's a musician, a filmmaker, a curator, programmer of Third Run Cinema, and a member of the Minister's Creative Council here at the ACT. Jim, Hannah - thank you both for being here.

Tonight's event is timely for two reasons. Firstly, as I think everyone in the room will already know, this year marks the 50th anniversary of the film version of 'The Rocky Horror Picture Show.' And tonight's conversation between Jim and Hannah will be followed by a viewing of a new documentary 'Strange Journey' about the making of 'Rocky Horror.' And the second reason for this moment of celebration tonight relates to Jim Shaman's archive here at the National Library. We are delighted to announce that Jim Shaman's visual diaries, a stunning visual record of his career over many years, which we are very proud to hold here at the National Library, has now been digitised and is available for everyone to share through the Library's digital platform, Trove.

We're enormously grateful to Jim for entrusting us with this material and for his encouragement and support in allowing us to bring this wonderful collection online for everyone to enjoy. This is a visual resource that fans of Australian cinema and performing arts will make use of for many, many years to come. So thank you Jim and I encourage everyone to search out this remarkable material on Trove.

Before I hand over to Jim and Hannah in just a moment, there is one further acknowledgement that I'd like to make. A great deal of our digitization work here at the Library is made possible through philanthropic support, and this digitisation project was made possible through a bequest from the late Frank van Straten AM. Frank van Straten was a remarkable historian of the performing arts in Australia, the first archivist, and then director of the Performing Arts Museum at the Arts Centre, Melbourne and the author of many books on the history of performing arts. I want to acknowledge Frank's memory and his generosity in making it possible for us to share Jim's visual diaries online. And now, ladies and gentlemen, would you please join me in welcoming Hannah de Feyter and Jim Sharman in conversation. Thank you.

Hannah de Feyter: Hi everyone, I'm Hannah. I'm here from the National Film and Sound Archive. Thrilled to be partnering with the National Library to talk about this incredible collection of visual diaries. Jim, you have really set us a considerable assignment this evening because not only did you direct so many productions that we have to talk about, you've also made this truly incredible personal archive of visual diaries. I just want to say I spent many hours going through these diaries and the pages that you will see this evening are not even 1% of the content. You could have designed 500 different presentations of images to talk about this evening. So I've done my best to pick a few highlights, but I cannot recommend enough that you have a look at Trove and dig through, have a rummage through yourself of these. There's travel diaries, there's correspondence, there's set design imagery, there's all sorts of absolute treasures, all of Jim's inspirations, some of which we're about to start talking about. And so yeah, I highly recommend you get on Trove and have a look around because it really offers this beautiful glimpse into sort of a window into this incredible creative life. So thank you not only for your creative endeavour, but your archival endeavour and making that available to the public via the Library. That's just incredible.

So I'm going to start by talking about, Jim, a container that people use to describe you quite a lot, which is this idea of highbrow lowbrow. Even on the front of your memoir, 'Blood and Tinsel', Baz Luhrmann uses that to describe you. He says you're pop, you're highbrow lowbrow and looking at your collections of imagery in the diaries, that's really apparent here. We have London Symphony Orchestra, we have 'Alien,' we have visual art, we have some political inspiration. And as we look through here, we've got articles about Luna Park, we've got visual art again, we've got Fassbender movies, and your inspirations are clearly so broad, and that really maps up with this idea that you have directed across so many different mediums: musicals, opera, cult movies to Shakespeare. So I wanted to ask you, does this sort of label of high/low resonate with you? And what do you feel like drew you to such a broad palette of influences as an artist?

Jim Sharman: Sure. Well, I think I did come out of a pop art generation, and one of the tasks was to remove the categories of high and low [brow]. And certainly with my films, one of the things that I've often found confounded critics was mixing A-picture tropes with B-picture tropes. I dunno if anybody's seen 'Bugonia' of Yorgos Lanthimos, but it was like a film I made called 'Shirley Thompson vs. the Aliens' on steroids. I thought it was fabulous. But there is that, there is contradiction in life and through the work. And there also, I'd say to add to that, probably a comic tragic dimension to it as well, which is probably philosophically where I sit in a view of life and something which may be also help the connection with people like Patrick White. And indeed many of the writers that I work with, even though they're very different, Richard O'Brien, Sam Shepherd, Patrick [White], etc. And part of the joy was working with writers, but sharing something of those contradictions probably was part of it. And that probably also made it a little bit difficult sometimes for other people to understand.

Hannah de Feyter: Well, there's the contradiction and then there's also the similarity. I put these images together. This is from your Bell Shakespeare 'Tempest' with John Bell, and there's a beautiful oral history you did.

Jim Sharman: Reg Livermore as Frank-N-Furter in the Australian production.

Hannah de Feyter: Yeah well, and there's a beautiful oral history that you've done for NFSA where you talk about Frank-N-Furter as Prospero and the connection between those two. And so even though they're sort of tonally different or different in terms of the tropes, there's so much similarity in terms of the story maybe. Do you experience them as different?

Jim Sharman: There's a few things to unpick there. First of all, when I was doing 'The Tempest,' I suddenly realised that there had been a big picture version of it called 'Forbidden Planet,' which is probably what Richard O'Brien had loosely based his original idea of 'Rocky Horror' on. And mad scientists, strange servants, a couple of young lovers, etc. And suddenly I was doing 'The Tempest' and thinking, "I've been here before." And I think beneath many things, I mean, I think there's a great deal of confusion about art in particular Australia, where people seem to confuse it with current affairs. I don't think it's got anything to do with current affairs, I think. But it has got something to do with finding what's ancient in what's modern. And this is perhaps something that might connect things that otherwise seem very, very disparate. And I think that's one example.

But also I'd have to say that making that connection was retrospective. And in many ways I wouldn't believe too much of what I'm saying tonight if I was in the audience. Because the truth of the matter in my case, and I would suspect also in some of my collaborators, notably the designer, Brian Thomson, who I sure will get to later, it was totally intuitive. In fact, "It seemed like a good idea at the time," could be the answer to many a question about this work. But then subsequently, you can look back and suddenly there you can suddenly walk through the labyrinth and see that there's a link and where the minator is and what the way in and out is.

Hannah de Feyter: Is directing those different kinds of productions different? Like here we've got you directing 'Shock Treatment.'

Jim Sharman: Shock Treatment with Barry Humphreys, Richard O'Brien, and who else? Yes, Jessica Harper.

Hannah de Feyter: And we've got your diagrams from 'King Lear' I believe. Is directing Shakespeare different?

Jim Sharman: It was early 'Shock Treatment' was midway. When you start off early as a young director, you usually do a lot of directing. What you discover later on is when not to direct, and that's actually the art of it. But notionally, the preparation tends to be similar. But of course if you're doing an opera, you're dealing with singers who have got a very disciplined way of thinking because they're trained in music and so they like a degree of precision, whereas actors might like more freedom, creativity, improvisation, so forth. So there is a shift in emphasis between each of the things. But I never particularly found a big difference in shifting from one media to the other. And I thought the differences were somewhat exaggerated, although I had been accused of doing cinematic stage productions and theatrical films, and probably guilty as charged.

Hannah de Feyter: Well, if we dip into one film to begin with and one stage production to begin with, I'm interested to talk about 'Shirley Thompson vs. the Aliens,' which is your first feature featuring notably some Luna Park inspired by that article earlier. We have some images from 'Shirley Thompson' here. What was it like directing this film?

Jim Sharman: Well, that actually came after I'd done some of the early musicals, and I actually had some money and I'd just come back from Japan. I directed 'Hair' in Tokyo, and I had some money from that. And so I thought, let's make a film. Cos nobody had made any films. I think Tim Burstall was about to make his first film. And so I went to what was then set up, I suspect by the Gorton government, was it? The film, the first film funding body. And they said, "Oh, well if you put it through, we'll put it in process and in six months we'll give you a decision." And I said, "Well, we'll be done by then." So we just went out and I said, "I dunno how to make a film. Let's just make one." And we did. It was $16,000. We shot it and it was written by a good friend and actor who I had been through [National Institute of Dramatic Art] NIDA with Helmut Bakaitis, who was also a writer. And we shot it in three weeks. And we edited very fast. It was, I think, edited by somebody who'd been in the Israeli military who edited with karate chops as seem to recall. And I think it only got a few screenings at the film festival, and everybody absolutely hated it. But the next day I was on a plane with Brian Thomson heading to London to do [Jesus Christ] 'Superstar' there. So things were moving pretty fast at that time.

But the interesting thing about 'Shirley Thompson vs. the Aliens' is that it does deal with science fiction, rock and roll, etc on one hand. And it does deal with a suburban character, Shirley Thompson, indeed has a psychological breakdown as a result of her encounter with the alien, hence the 'Bugonia' reference. And so in a way, it was the template for other things that were to come. A template in a way that made seeing 12 pages of 'Rocky Horror' called 'They Came from Denton High' and realising this could be something fantastic, whereas everybody else is saying, "don't touch it." And also, similarly, 'The Night the Prowler' of Patrick White's as well. So there's kind of tentacles coming out from one thing to another.

Hannah de Feyter: And you'd catalogued some real 'B movie' style inspirations in your diaries.

Jim Sharman: Absolutely, yes.

Hannah de Feyter: Do you remember when...

Jim Sharman: A and B.

Hannah de Feyter: A and B. Do you remember when you started seeing those movies and loving them?

Jim Sharman: Certainly. I started off seeing them as a kid at Saturday matinees, and I was very affected by what were then in that era, Saturday serials like Orson Welles' 'The Shadow' and things like that. And I loved a lot of those tropes from those kind of Saturday serials and indeed used them in both that film and also very heavily in 'Rocky Horror.'

Hannah de Feyter:

As an alternative to the sort of 'B movie' tropes in 'Shirley Jackson' when we talked about the...

Jim Sharman: 'Thompson.'

Hannah de Feyter: 'Thompson.' I keep saying 'Shirley Jackson.' Golly, what you described as the high point of your theatrical work is this adaptation of 'A Cheery Soul,' production of 'A Cheery Soul' that you did as the opening show of the Sydney Theatre Company. And I feel like this image for the production sort of holds some of those tropes as well. Can you tell us?

Jim Sharman: It does, and I think we'll obviously come to the connection with Patrick [White] a little later and also the working with Brian Thomson. But I think there are a couple of moments where the work, particularly with Brian peaked, and I would say two of those were 'A Cheery Soul' and Benjamin Britten's 'Death in Venice.' And we'll maybe talk about both of those later. And I think it was also, I think it was the first moment that the stage, there was a problem with the stage at the Sydney Opera House because it was never meant to be a theatre. And so it was meant to be a cinema. So it had a Panasonic Panavision stage, and everybody was trying to pretend that it was the little proscenium arch and do things. And we had a couple of shots at it ourselves. And I had also had it shot it with the designer Wendy Dickson one season. So quite effectively. But the really best version of that, and I think Brian's who I think initially was a great pop artist, but finally became a great minimal stage artist as well, was with 'A Cheery Soul,' with the influence perhaps of Christo, because I know he was involved in helping wrapping the coast with Christo back in the day and maybe touch of the circus tent, the empty stage, the Brechtian lighting.

It was fascinating in terms of 'A Cheery Soul' because it was not thought to be one of Patrick [White's] best plays. It had opened and shut in Melbourne and got a one line review: "A Cheery Soul is a dreary soul." End of story. And I realised somewhere in there, cos I read it and I thought, "This is the greatest Australian player I've ever read. What are they fucking talking about?" And this is a Greek tragic comedy in an Australian context. And by casting Robyn Nevin, who was not at all like the description of the cheery soul who was meant to be a huge kind of big country woman kind of figure. And she was only 40 at the time. But nonetheless, as we worked on it, and working with Brian, who suggested stripping the stage right back, cos it had a kind of short story structure where everything began realistically and then slowly it became more abstract as the protagonist moved into a kind of slight craziness towards the end. Almost like Lear on the heath.

But Brian's suggestion was just strip it all away and let's start with nothing. And that kind of production with the empty stage, the cast presenting themselves to the audience to a chord of music and a stunned silence in the audience. And Patrick [White] later said, "I hadn't seen anything like it since the opening of 'Oklahoma.'" He was very excited. It created a kind of template for stage production, particularly in that theatre, but I would say is now pretty much standard. And it also turned a play that had been dismissed in one line to be revealed as a classic play. It was subsequently done by Neil Armfield, who also did it with Robyn [Nevin] and did it with Carole Skinner, Kip Williams, who's recently done it. And so there's kind of a tradition of Patrick White plays.

It's interesting because at the time he was obviously thought to be the great novelist that indeed he was, and people felt his involvement with theatre was a distraction that he should not be involved with. But the truth of the matter is the novels have slightly receded, but the plays are still being done. And they become something of a template for directors to actually test themselves in a way, because one of the things about [Patrick] White's plays, talking about the ancient in the modern, was he was not interested in the theatre as current affairs at all. He was interested in, if you get a play like 'The Season at Sarsaparilla,' you get on stage three kitchens: heaven, earth and hell. And you go back to the mediaeval theatre where it came out of the churches, the sermons became soliloquies, you had a cart for heaven, a cart for Earth, and a cart for hell. And he kind of did that with the Australian suburban landscape, and he was the first person to do it. And it was the first time we'd seen that kind of notion of Australian suburbia presented in mythical terms to an audience.

And I first saw that in John Tasker's production when I was still a NIDA student about 18. It stayed with me, and we maybe will get to later the point at which that began to kick in. But there was a point where I had to stop doing big musicals, which was after 'Hair,' 'Superstar' and 'Rocky Horror,' which I think in a way defined an era. And it went from 'The Dawning of the Age of Aquarius' to 'Frank’n’Furter, it’s all over.' And that was an era. And then coming back here and stepping into deeper waters with the White plays and then the subsequent effect of them in terms of some opera productions, including 'Voss' and also Adelaide Festivals and so forth. But we'll get to that.

Hannah de Feyter: Yeah, I mean, I would like to maybe jump in on the opera. Because you had had some experience with sort of stark stage design before your very early career production of 'Don Giovanni.' Which was apparently quite contentious. And I'm interested in you often having this sort of slightly provocative relationship with the audience. Bit of love, bit of hate. Did you expect this when you were preparing this 'Don Giovanni,' did you think it was going to be very shocking to people?

Jim Sharman: I don't know that you never, that you actually think that at the time. But certainly, what I was actually meant to do was a revival of a standard repertoire production. But I did have in Stefan Haag, who was a man who was running the opera company at the time, somebody who did see some potential in what I was doing. Up until then, I was pretty much an experimental theatre director and I was a jobbing director. But I asked, instead of doing the revival, if I could come up for the same money, if I could do an original production. And he said yes.

And at that stage, because I was yet to meet Brian Thomson, I was still designing my own production. And I come with something which actually philosophically is still possibly quite interesting, which is that 'Don Giovanni,' basically the chessboard life is a game. And finally with the images behind it, it was kind of Brechtian stage. And that got rid of all of the balconies with trellis and stuff. Decorative stuff that was constituted conventional theatre at the time. And people didn't like that. It was white lit and it was very stark. And also it was basically one of the early uses of projection, slightly clumsy as I recall, of all of his crimes, finally accumulated at the end. He was checkmated and fell off the board - end of opera. It was very simple, very simple.

I don't know what it would be like if I saw it now, but it absolutely infuriated critics. And the headlines were, "I walked out" and "Desecration of a masterpiece." And so I went to the theatre the next day and there was some cub reporter from the afternoon paper saying, "Oh, you poor young thing. Well, how do you feel? Everybody being so mean about your first production?" And I said, "Well, what would you expect in a provincial berg like Melbourne?" And the paper then came out with "Director Strikes Back" and suddenly I was on television arguing with elderly Viennese critics. And they then turned around and rather sneakily said, "We don't admire what you do, but young man, we really admire you." And I said, "Well, I'm afraid I can't return the compliment." And then there was lots of young people going to the opera and old people throwing their programmes at the stage and walking out.

And the publicist for that happened to be a man called Harry M Miller. He was about to do 'Hair.' Stefan Haag left the opera company. He said, "Why don't you get him to do it? He can empty the theatre of old people and fill it with young people. That's what you want." And so that was how that happened. And that was, I think, the first Australian to direct an international musical that had never happened. The stage was full of American and English theatre. It was very rare to hear the Australian voice on stage. And it was very rare for Australian creatives to be heavily involved in major work at that stage. With some notable exceptions like Barry Humphreys and so forth who were just emerging at that time. But yeah, that and 'Hair' essentially changed everything, including Australia.

Hannah de Feyter: I love this slightly threatening promo for 'Hair': "God and the chief secretary willing, Jim Sharman will direct 'Hair.'" But 'Hair' also had quite a contentious perception.

Jim Sharman: 'Hair' could have been a massive investment that was closed down on the opening night. There was no question about that. That was the threat. And it's very hard to think of it now because everybody knows the songs. Basically. You'd hear it at a supper club, but at the time there was conscription and there was a war, and it was a very savage indictment of the war. And I think it actually changed people's attitude to what the Vietnamese called the Pacific War, but what we call the Vietnam War. And I think it also helped, it broke censorship in every city that it played in every stage in Australia. It also, I think, created the mood that elected the Whitlam government. It was the answer to 23 years of conservatism. And it also introduced all the problems that everybody's still arguing about today.

Hannah de Feyter:I mean, so much of your work is about trying to shake people out of this sort of suburban...

Jim Sharman: Well I came out of that 23 years of conservatism. So naturally, yeah, I don't think I was alone. I think I had many colleagues doing exactly the same thing. But 'Hair' I think was exceptional. And interestingly, again, the ancient in the modern, that you're basically getting a dionysian spectacle unleashed on a parochial conservative society. And they didn't all love us for doing it, many did, but it was the only time where we had bomb threats and clearing theatres and being spat at in the street and so forth. But it thems the breaks.

Hannah de Feyter: I mean, I'd love to bounce back to your film work and ask about 'The Night the Prowler,' because that feels like it has a very similar sort of desire in terms of how it hits the audience. It's the one piece of film work you did with Patrick White?

Jim Sharman: Yes, it is. And it's from a short story. It's complicated. If you see the film and don't know what actually happened, it's a drama. But once you do know what's happened, you realise it's a comedy. And so it almost requires two viewings to see it. But my film work, it's the one that I'm happiest with. It's also a bit rough around the edges, but they all are because they were all made very quickly and they're all made for not a great deal of money. Somebody was saying the other day, what's the difference between 'Wicked' and 'Rocky Horror'? And I said, $149 million.

Hannah de Feyter: Although you had the option to make, not to segue, but you had the option to maybe make 'Rocky Horror' for more money, didn't you? And you very deliberately chose not to.

Jim Sharman: Which probably more by accident than design created the situation because I wanted to keep together the Royal Court cast, the central cast, Frank-N-Furter, Riff Raff, Magenta, etc. Happy to bring in two Americans, as indeed Brad and Janet enter into another world, etc. And Meatloaf had done the show in LA. So that was one option. The other option was to do it with rock stars, which would've given it some box office oomph at the time. But all the films that were made with rock stars at the time have vanished, whereas it hasn't. However, it meant when it opened, no one had heard it anybody in it. So it opened and shut like a door, and then the audience suddenly found that the late night thing happened, and here we are 50 years later interminably talking about it.

Hannah de Feyter: Well let's talk for a bit more about 'The Night the Prowler' then, if you're tired of talking about 'Rocky [Horror].'

Jim Sharman: Sure. Well, I suppose it came out in a way I'd done 'Sarsaparilla,' which was the kind of suburban world of Patrick [White], and I thought we could do something from one of Patrick's short stories. And he thought either 'The Cockatoos' or 'The Night the Prowler.' And having seen 'Shirley Thompson vs. the Aliens' took it a little bit towards 'The Night the Prowler' because there is that kind of connection there. It's like that aspect of 'Shirley Thompson' enhanced and dug a deep, because it does begin as a comedy of manners, including with the wonderful Ruth Cracknell who has a particularly fine way of saying the word 'Canberra.' And it's the only film, I think, with Canberra jokes in it.

Hannah de Feyter: They're fantastic Canberra jokes.

Jim Sharman: You should be hugging it here. And then as it develops, it becomes more of a kind of metaphysical kind of journey for the protagonist as she cuts herself out of that suburban world. And so there are a few things going on, and maybe a few too many for some people, but not for me.

Hannah de Feyter: Well, this is my personal shout out to 'The Night the Prowler.' I think it's a fantastic film. But we sort of segued away from 'Hair' and this sort of series of three bigger rock musicals you worked on. We've talked about your sort of slightly contentious, provocative relationship with the audience, the hatred of the critics, but there's also very intense love. Here's your certificate for 'Jesus Christ Superstar' - the longest running musical in British theatre history. When you took your version of 'Jesus Christ Superstar' to London, were they quite surprised to be getting the Australian version there?

Jim Sharman: Well, first of all, there's just a brief bit of history. There were two versions of it here. First of all, there was the rock concert version, which played outdoor arenas and allowed myself and I think Brian Thomson to satisfy a few rock and roll dreams. And then we did the stage version, which was very operatic, and we did it like an opera - it is in truth through-sung. And although opera aficionados might be horrified of the thought, it's probably the most successful opera of the last century.

But Tim [unclear] saw it and the Broadway one had not worked so well. It actually was a very interesting production of it, I thought. But nonetheless, it didn't fly. And so they asked me to do it. Robert Stigwood asked me to do it in London, and I said, I would do it if Brian [Thomson] could do it with me. They didn't like the opera version. They wanted something closer to the concert version. We ended up doing a kind of version that I remember Bill Gaskill, who was a English director at the time running the Royal Court, said, "Oh goodness me, that could have been at the Royal Court." It was quite a stark version of it, not at all like a West End musical.

And certainly while we were doing it, there was a lot of talk about, because the notion of Australians doing things in London at the time was quite unusual. And the guys in the pub next door, which is the pub where Francis Bacon used to get drunk, by the way, said: "And then we heard we were getting the Australian version, well." However, then it opened, and indeed the critic from the Sunday Times who was the most influential at the time said, "The Kingdom of Heaven will open to receive this production." And so it ran nine years. And it was a bit better than "desecration of a masterpiece" as a byline.

But having got to London and done that, I was then a little bit at a loss, as I have been quite often between things, but found a new home at the Royal Court Theatre. And when I was there, there were the Kingdom of Heaven stuff lying around the table. And so they said, "Do come in and do something with us," but not, they'd scheduled the main theatre, but do something upstairs.

And I then ran into a friend from Sydney who was a drummer, and he'd run into a drummer in Spain. This is how it all happens. It's not wonderfully conceived. And it was a total pileup of accidents. And his name is Sam Shepard. You should meet him. So I gave him a ring, met Sam Shepard, and then I started talking. He said, "What have you done?" And I started talking about 'Shirley Thompson vs. the Aliens,' and he said, "Well, I've written a play about an alien called 'The Unseen Hand.'" And so I did that cast Richard O'Brien as The Alien, and he said, "I've written a musical," and you'll get more of that story in the film that's coming up later on. But that was how all of that happened.

And I would have to say, and I thought this because I was at the NFSA screening of the new 4K version of the film ['The Rocky Horror Picture Show'], which I have to say looked and sounded wonderful, and how much it owed to the fact that it actually came out of the Royal Court, that if it had been done commercially or in almost any other way, it would've become something completely different. And there was something about the Strangers. I mean, they were a bit shaken by us doing it there because it was definitely high art, serious English socialist drama theatre. And I remember Lindsay Anderson saying, "Are you turning this place into a brothel?" And I said, "Well, it's a start."

And anyway, and I had been mentored to some degree by Tony Richardson when he was here doing 'Ned Kelly,' because 'Hair' was on. He was interested in young directors, and I got a bit of experience of film that was about the only experience I actually had with him. And interestingly enough, he had done, when they did a history of the Royal Court Theatre and the plays that people liked most, there were two answers. One was 'Look Back in Anger' directed by Tony Richardson and 'Rocky Horror Show,' which I did. And so we had that kind of curious link there. But anyway, I think I've drifted.

Hannah de Feyter: Well, I think it's interesting that as well as this very contentious, provocative relationship with audiences, both '[Jesus Christ] Superstar' and 'Rocky Horror,' both the stage and screen version have this sort of devoted cult fans that sort of, I picked this headline that says, "Not so much an audience as a congregation," which is very appropriate for '[Jesus Christ] Superstar.' Do you connect with or relate to this idea of cult following?

Jim Sharman: I have mixed feelings on the matter, and we could maybe talk about that. Oh, we are talking about 'Shock Treatment.'

Hannah de Feyter: Yeah, this is my very elegant segue into 'Shock Treatment,' Jim.

Jim Sharman: No, no, no, no. Well, there was a desire to put the band back together again and do something with the 'Rocky Horror' team, which was probably a bit mercantile from the point of view of the producers. But I didn't think there was a sequel to 'Rocky Horror' because I thought it was self-contained in the thing in itself. But I was very happy with the idea that rather like carry on movies or Hammer Horror movies, that there could be something involving the same cast. So you could, for instance, put Brad and Janet through the wringer in some other different way. And Richard picked up on that idea. He had some songs that were already from a kind of sequel, 'Bitchin' in the Kitchen' being one of them, that kind of kicked off that idea. And that there was also a great enthusiasm for kind of wellness centres and things at that time. So we started off with 'Shock Treatment' started off being the notion of this kind of tyro running a wellness centre in Denton, and we went to Denton, Texas. There is an actual Denton.

Hannah de Feyter: These are these images here.

Jim Sharman: And we were going to shoot it on location, and there was an actor strike. And that was not the only reason. It was one reason we couldn't shoot it in the States. And Brian Thomson in fact came up with the idea of setting it in a TV studio. And so we kind of, well ahead, two decades ahead of it actually happening, invented reality television, the notion of an entire town being consumed by reality television being run by a megalomaniac tyro. And so we ended up with something that's predicted the world that we are now living in. But we're about 30 years too soon. And the audience were pretty horrified what they saw, I think. But it had a great score.

Hannah de Feyter: I love, in one conversation you described 'Shock Treatment' because so much of shock treatment is about sort of fandom and obsession and...

Jim Sharman: Well, the other thought that it was there at the time. Richard had the thought of the 'The Corsican Brothers' of Alexandre Dumas. That was the idea of the twins in it. But I also was greatly affected by, as everyone was, by the Jonestown massacre, the Kool-Aid. And it did occur to me in a darker moment, of which I do have, that when I went to see 'Rocky Horror' at the Waverley with the cult fans, I thought, "Well, if Tim Curry walked in now and said, here's the Kool-Aid, they would've drunk it." And so in a way, 'Shock Treatment' bit the hand that fed it and got slapped down a little bit because of it. But it is, again, I think a very interesting and slightly contentious good film.

Hannah de Feyter: Well, the thing that is so incredible about [Shock Treatment]...

Jim Sharman: And very comic stripy.

Hannah de Feyter: Yes, yeah. Well, and the design, the whole film is, if you haven't seen it, it's set in a TV studio and the camera's sort of moving around and there are these walls of screens. And a name that has been coming up over and over and over is Brian Thomson, your very close collaborator. How did you first begin working with him, and what do you think made you so simpatico as collaborators?

Jim Sharman: I was about to do 'Hair.' I think I was in rehearsal for 'Hair,' and it's a bit of a classic story. I met him in a queue in a hamburger takeaway, which is curiously apt, and was introduced. And he was an architecture student who was very much influenced by Buckminster Fuller, Marshall McClure and other figures of that time, had absolute contempt for the theatre. And I thought, "Fantastic - what we need." And so I think the first thing we did was 'As You Like It' of Shakespeare. Brian did then redesign 'Hair' for Melbourne, adding to what was already there. But the interesting one was, and it was a kind of rosenquist kind of pop art thing. He was totally, when I first went to his place, he had seven television sets on with the sound off and a juke box playing while he worked quietly in the kind of island of concentration, the drawing board in the middle of it all. And I thought, "This is great." But that was not totally uncommon at the time.

And with the, 'As You Like It,' he came up with a kind of illuminated white box for the austere court, and then we billowed a mottled parachute over the audience's head. And when they looked back, it was gone greener - we were in the forest of art. And I think it was referred to by some people as more soda pop than champagne, than vintage champagne. Which it may well have been, but it was certainly a breath of fresh air in Shakespeare production.

Hannah de Feyter: Well, then you've got the high and the low there as well.

And that got us going. But I think it was certainly the time at the Royal Court after '[Jesus Christ] Superstar,' we did a play of that play I mentioned of Sam Shepard. Brian filled the theatre with grass, had the audience sit on the grass, got a Cadillac, brought up bit by bit, and assembled in the middle of it. It was set in a place called Azusa - everything from A to Z and the USA, and that was painted on the car. And there was Richard Hartley who would become the musical director of 'Rocky Horror' tinkering away on a ragtime piano in the corner. And that was the prelude. And many of the cast of 'Rocky Horror' kind of segued into 'Rocky Horror.'

And the only thing I'll say about that in terms of Brian, was that he created in that space, which was really quite tiny for any of you happen to know Belvoir downstairs in Sydney. It was that small. He created a haunted cinema in there. He created a kind of, and so what was a haunted cinema at the stage, performing in front of a screen, ended up haunting cinemas when it became a film. And now people are doing shadow cast versions in front of a screen, which cures the echoes, what Brian originally did at the Royal Court. Though the actual stage production is now done in a way totally different to what we did, but I think ours was probably a very early version of an immersive theatre. And it was probably also the one time when 'Rocky Horror' actually lived up to its name and was actually scary.

This image is from one of the most iconic designs that you worked on with Brian [Thomson] for 'Death in Venice.'

Jim Sharman: Absolutely.

Hannah de Feyter: And you've described that as a work that changed everything for you. What did this production of 'Death in Venice' mean?

Jim Sharman: Well, I think again, you have that moment in that image that was described as one of the most sensual moments in Australian theatre, and may well have been. It was basically, Brian and I, it was before Brian fully came back to Australia, he was still in London, I think, when he was doing it. And I had also done Strindberg's 'Dream' play shortly before that, I think. And there was a kind of sense of Aschenbach living in a world that dissolved and came and went behind him. And the set was black, and it just kept opening up like a Borges labyrinth, the famous garden of the forking paths. And then when it got to the sea, this almost like underwear, this kind of billowing white silk poured down, and everybody ran into it to the sea as the music swelled, and it was pretty amazing. But somewhere in there, you can still see circus tents, many of the other kind of tropes that inhabited both our lives. And with the kind of shared imagery.

Hannah de Feyter: I included this one just because I loved it. This is an example of the sort of very sweet little details you can find if you click through the diaries on Trove. But there's this very hip letterhead from Brian Thomson. And also, I really like this cake based on 'The Scream.' That was just a little cute addition. But kind of as a result of this work...

Jim Sharman: Out of 'Death in Venice' came not long after 'Cheery Soul,' and as a result of that, I was then asked to do the Adelaide Festival, which became one that had Pina Bausch and Elijah Moshinsky - his production 'Metropolis,' which Brian [Thomson] designed. It had lots of Australian premieres, and it kind of revamped the notion of, it had already gone through a major change with Christopher Hunt before me with the festival. Indeed him, it was a bit of a battle to do 'Death in Venice' cos I still came with a little bit of a whiff of "the rock and roller being serious" about me, but I think it was maybe the administrator Mary Valentine, who persuaded Christopher [Hunt] that that might be a good idea. And it turned out to be so. And it turned out to be probably the most revived of all of the opera productions that I did. But as a result of that, I was then asked to do the Adelaide Festival.

Hannah de Feyter: And on this side...

Jim Sharman: And that was when I stopped Maggie Kirkpatrick I think, the actress said, "Well, you're now part of the establishment whether you like it or not." And that was the shift point from the notion of getting away with being young and radical and suddenly having to be mature and sophisticated and all those things.

Hannah de Feyter: Although looking at these Adelaide Festival papers, there is a real sort of radical spin on them. Like on this side, you definitely can't read it from the audience, but there's a little bit of a manifesto for the Adelaide Festival. Starts with point one: "To provide a unique celebration of artistic endeavour." And it's quite a radical set of ideas in some of this. And even your poster for the Adelaide Festival, I sort of was laughing as I was going through because even the poster caused a stir and people didn't like it. The headlines here, "Film poster defended," "A shocker to grab the eye." So you kind of couldn't escape provoking people even once you'd joined the establishment.

Jim Sharman: Maybe.

Hannah de Feyter: A big part of that, you sort of talk about this moment in 1975 where you decided to come back to Australia. And we're sort of bouncing around chronologically on our own garden of forking paths. But I wanted to ask about that moment in connection to then going on to do this work for Australian art via the festival. What does it mean to you to be an Australian artist and what brought you back here?

Jim Sharman: Sure. I think it's good that we aren't being chronological, but I hope it's not too confusing for people. But in the midst of a whole kind of tossing out productions of 'Rocky Horror,' a bit like pancakes, we did three in London, one in Sydney, LA, New York, and the film in the period of time, which was finally a little pretty exhausting. I did 'Threepenny Opera' at the Sydney Opera House for the opening of the Sydney Opera House. And my notion of musicals was never Rodgers and Hammerstein, it was always [unclear] really. And in a funny kind of way, 'Rocky Horror' is kind of a latter day 'Threepenny Opera' and 'Shock Treatment' is 'Mahogany.' And in the same way that that encapsulated the [unclear], maybe we captured something of the 1970s. Cos they were the two artistically most interesting periods of the last century.

But when I did that 'Threepenny Opera,' I just loved hearing the sound of an Australian audience, and I recognised that I'd become very detached from, I was doing shows and they were running for years, and they were being recast, and I'd be rehearsing people I'd barely met, and I felt a kind of distance from what I was doing. And I also felt that I was also pretty exhausted. I remember doing a Sam Shepard play at the Royal Court 'The Tooth of Crime' and coming out for a breath of air during a rehearsal and running into Barry Humphreys in the street who looked at me, looked me up and down and said, "Oh dear." He said, "You know there's a time for young people to go home," and he wasn't maybe wrong.

And anyway, I decided around the time of the 'Threepenny Opera' opera before I went back into the other rocky things to come back. And so then we did 'Rocky [Horror]' on Broadway, which opened and shut like a door. The movie opened and shut like a door. I came back to Australia, but I wasn't quite sure what to do. And the management of the Old Tote, which was the predecessor to the Sydney Theatre Company, rang up and said, "You can do whatever you like. What do you want to do?" And I said, I'd like to do Patrick White's 'The Season at Sarsaparilla.' And they said, "Well, that's the one thing you can't do because he won't allow anybody to do his plays." And I said, just pick up the phone and ask him. And they did. And there'd been an interesting history there, because I had done a show called 'Terror Australis' which had really frightened the horses, except for Patrick White, who was the one person who wrote a letter defending it at the time. And that history it kind of sat there. And so we then met and got on extremely well.

I did '[The Season at Sarsaparilla]', which was probably one of the first at the time. It had been done, in the production I remember about [unclear] a little bit decoratively. But we took all of that away and just put three kitchens as three vivisection slabs on stage and then filled it with film stars basically of the time. Max Cullen, Bill Hunter, Kate Fitzpatrick, Robyn Nevin, Michelle Ford and figures of that period. And it was great. And the audience were now 10 years away from being the people of Sarsaparilla so they could smile. And Patrick [White] turned to me and said, "I might write something for them next time." And that became 'Big Toys. And so he then started reengaging with the theatre. And I think it gave him more stimulus also for his literary work as well.

And so that changed things, but not as much as 'Cheery Soul' was to do a little bit later because that was the play, because of that one line review, he'd stopped being involved with the theatre. And suddenly for the play that had been dismissed to be revealed as a great Australian classic, changed everything for him. It was dynamic. And here, I think with these photos, Brian Thomson did an amazing thing actually on the opening night of 'Big Toys' because in a conversation with Patrick, he came across this list that 5-year-old Patrick had written to Santa: "Dear Santa, this is what I want for Christmas." And it was quite a list, and it did end by saying, "I know I'm very greedy."

But anyway, Brian got together all of these things and put them in a bag, and on the opening night of 'Big Toys,' gave it to Patrick. And you see in that photo there, because Patrick's famously unsmiling face on the cover of every one of his books, but he's never been happy because he opened the parcel, took the things out, and he finally got to the little mouse that runs across the floor and realised what it was, and burst into tears, then burst into laughter. And it was the most, on the kind of human outside, the theatre of it all things. It was one of the great experiences of that moment at the time. And that's also a rather great photo of Brian behind his Magritte apple mask.

Hannah de Feyter: So it's not just Patrick White whose work you've really brought attention to in terms of Australian theatre. And it's not just these great international artists that you brought for Adelaide Festival. You also did this work with Lighthouse Theatre highlighting the work of other new Australian writers.

Jim Sharman: Notably with [unlcear] and Stephen Sewell. And again, the writers that I felt had a kind of slightly international desire to not make the theatre parochial, to make it, to take it out from the big world, and to use a big stage and have epic themes and epic ideas, and to encourage that and put it on a big stage. To some degree, we shifted the subsidised theatre model into being able to do that was suddenly something you could do. I mean, we weren't the only ones doing it, but we did it. We were the only ones who did it, I think we did seven plays a year, and four of them were premiers and nobody was doing that. Whereas now they would do it.

Hannah de Feyter: A thing that has come up again and again, maybe as a way of sort coming to a close, is this theme of curiosity and of putting on this new work. And also here we have an image of a NIDA cast that you worked with working with young people to do a Strindberg production...

Jim Sharman: Strindberg's 'A Dream Play' - a wonderful play. Yes. That had Baz Luhrmann in it. And certainly, I think in a funny kind of way, Baz and Catherine took up what Brian and I had been doing. In fact, Catherine once said to me, we just would work out what you and Brian would do, and did the opposite, and it always worked.

Hannah de Feyter: So if you wanted to finish by thinking about legacy and young artists, what advice or encouragement might you give to any sort of curious young person who has this same hodgepodge of influences and this same desire for new exciting work? Do you have any advice that you'd offer?

Jim Sharman: Well, I was governed initially. I don't actually think I had a career. I think it sounds quite pretentious to say I had a vocation, but I think it was closer to that than the other. And I think I was driven by curiosity. I didn't understand the world. I wanted to understand the world. At that moment in time there was no film school. There was NIDA. I think it had been only there two years. And so theatre was a way of exploring the world, and then film became part of that, then opera became part of it and so forth. It grew. Today, if I had that same burning curiosity, I don't know that I would make the same choices.

I actually think there's an interesting parallel in centuries. If you look at things historically between out of the First World War came cinema, silent cinema, then it got sound, then it got colour, then it got wider, then it got bigger. It was definitely the medium of the last century. I don't necessarily think it's the medium of this century. Theatre, of course, has been dying since the Greeks, so it's not going to go away. But I don't that they would be the choices if you wanted to explore the world and talk to the world about itself. I think that, and I've set up this little future fund thing at NIDA. It's a small thing, may or may not, but in the hope of injecting some new art forms, I think I called for at this moment in time. I think there's a great notion of, oh, because after the first World War, we got the cinema, but after COVID we've got kind of a similar, which is the equivalent of the First World War, we kind of certainly got, we've got the Nazism, but we seem to have not got the art. So there's a bit of work to be done out there. And so I think that's for a new generation, but I think it is going to take a new art form and I'm yet to see it. And I don't think it necessarily is AI.

Hannah de Feyter: Well, if you're a young person in the audience, that's a provocation for you. Or an emerging artist of any age in the audience, that's just a simple assignment for you is "create a new art form." Well, we've been on a meandering and strange conversational journey. Thanks so much Jim. And fittingly now we're going to have a short intermission and then we'll be back for the film, 'Strange Journey.'

Conor McCarthy: Ladies and gentlemen, would you join me in thanking Jim and Hannah for an extraordinary conversation? And it's an extraordinary, rich and generous conversation. Thank you both so much. And as you said at the end, Hannah, also I think inspirational for creative people here and online to take inspiration from this archive from Jim's experience. We're now going to have a brief intermission. We'll return in 15 minutes with the second part of tonight's event, a screening of 'Strange Journey: The Story of Rocky Horror.' There are some refreshments upstairs, so please do take the opportunity to stretch your legs, enjoy some refreshments, and please do rejoin us in 15 minutes when Jim will introduce the film. We'll see you here at 7:15 pm, please. Thank you.

About the speakers

Jim Sharman AO

The stage and screen work of Australian director and writer, Jim Sharman, spans decades and eighty productions including early international and era-defining musicals Hair, Jesus Christ Superstar and The Rocky Horror Show. Jim co-wrote the screen adaptation and directed the international cult movie hit The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

Jim has directed countless premieres by writers as diverse as Louis Nowra, Stephen Sewell, Dorothy Hewett and Sam Shepard, and staged radical interpretations of classics, by Shakespeare, Strindberg, Lorca and Brecht. Notably, Jim revived and premiered the stage work of Patrick White, including Season at Sarsparilla, A Cheery Soul, Big Toys, Netherwood and the movie The Night the Prowler. He also directed Richard Meale's opera of Voss from David Malouf's libretto based on Patrick White's novel.

A NIDA graduate and Churchill Scholar, Jim was Artistic Director of the influential Lighthouse Theatre Company and the 1982 Adelaide Festival of Arts. Jim’s memoir Blood & Tinsel, charting the cultural progression from sideshows to opera houses, was published by MUP in 2008.

Jim is the recipient of a Helpmann Award winner for Best Director and also received the JC Williamson Centenary Lifetime Achievement award. He was recently appointed an Officer of the Order of Australia for distinguished service to the performing arts.

Hannah de Feyter

Hannah de Feyter is an Assistant Curator at the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia. She works on a variety of creative and cultural projects, including the flagship digital restoration program NFSA Restores which digitises, preserves and shares cult and classic Australian films; and Sounds of Australia, the archive's annual capsule of iconic Australian sounds.

Hannah's work involves collaboration with many other cultural institutions, including a recent retrospective exhibition of filmmaker Mary Callaghan's work with Wollongong Art Gallery, and a partnership with Transport Heritage New South Wales to celebrate the 50th Anniversary of beloved Australian rail film A Steam Train Passes. Hannah has also inquired into and presented the early work, influences and achievements of Australian performer, writer, arts advocate and festival director, Robyn Archer AO.

Hannah has presented NFSA Restores titles both nationally and internationally, including at the Deutsche Kinemathek, Harvard University, the Cambodian International Film Festival, and the Asian Film Archive in Singapore.

Hannah is the former co-director of the Stronger Than Fiction Documentary Film Festival and currently programs Third Run Cinema, an occasional social film series. She is serving her second term as a member of the ACT Minister's Creative Council.

This event is presented in partnership with the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

Visit us

Find our opening times, get directions, join a tour, or dine and shop with us.