Hopes and Fears: Exhibition themes

One of these photos may be of a relative who embarked on a long and difficult journey to Australia, helping make possible the life the family has today.

When you look at the picture of an ancestor, someone who may have spoken a different language, eaten different food and worn different clothes, it invites you to wonder why they decided to leave their home, and what it was like for them to arrive in a strange new country.

What were the hopes and fears that motivated them to change their lives in such a dramatic way?

Our national experience

Stories of migration are very much part of our national experience. The most recent Australian Census, conducted in 2021, tells us that more than half of Australians have at least one parent born overseas. Coming from all parts of the globe, these migrants help make Australia one of the most diverse nations in the world.

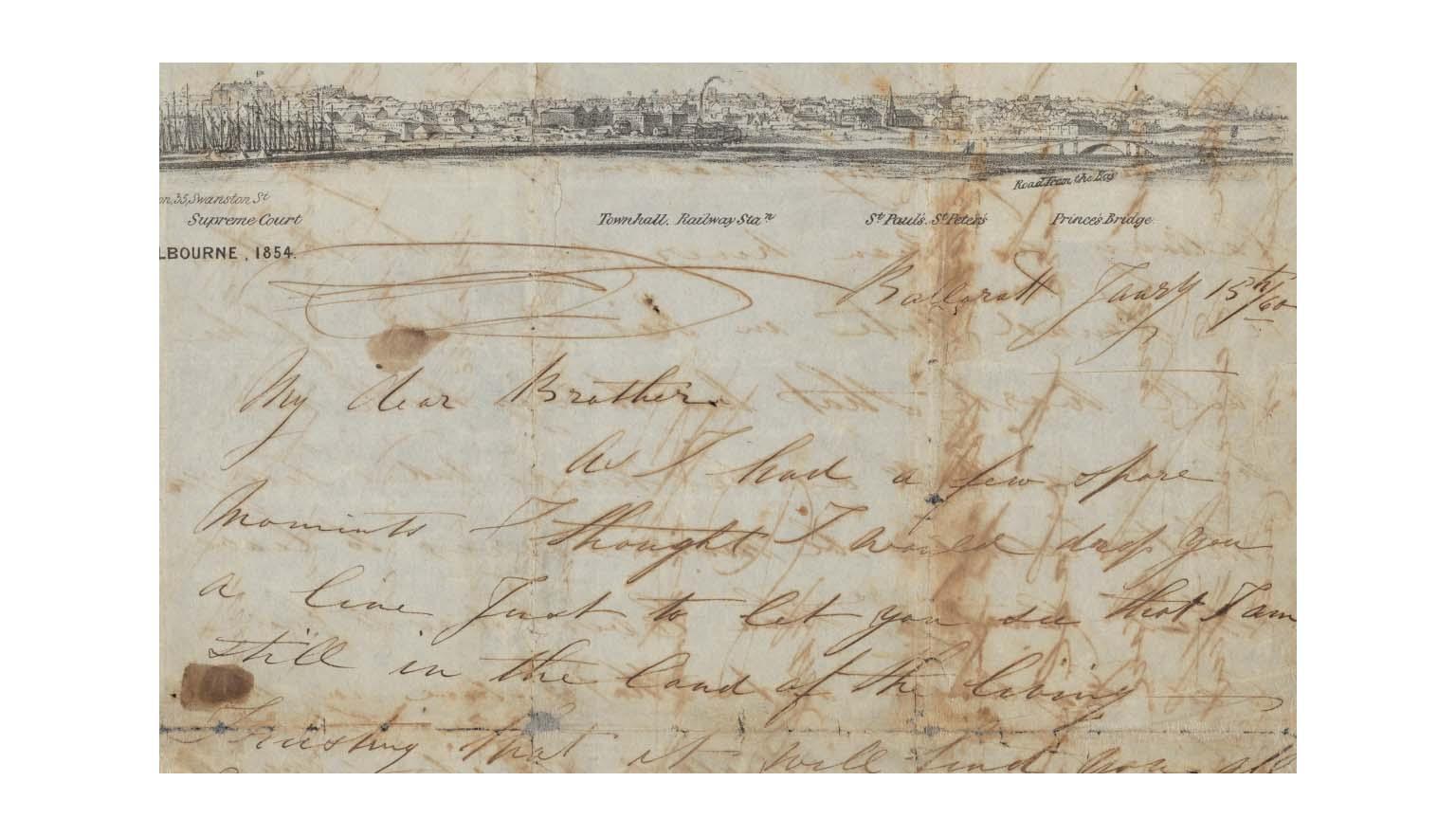

The National Library is a place where migration stories can be found and retold for future generations. The books, magazines, paintings, documents, letters, drawings and photographs held here provide a storehouse of memories for all Australians to cherish.

Hopes and Fears: Australian Migration Stories, running from 26 July 2024 to 2 February 2025, celebrates the people who have made those journeys.

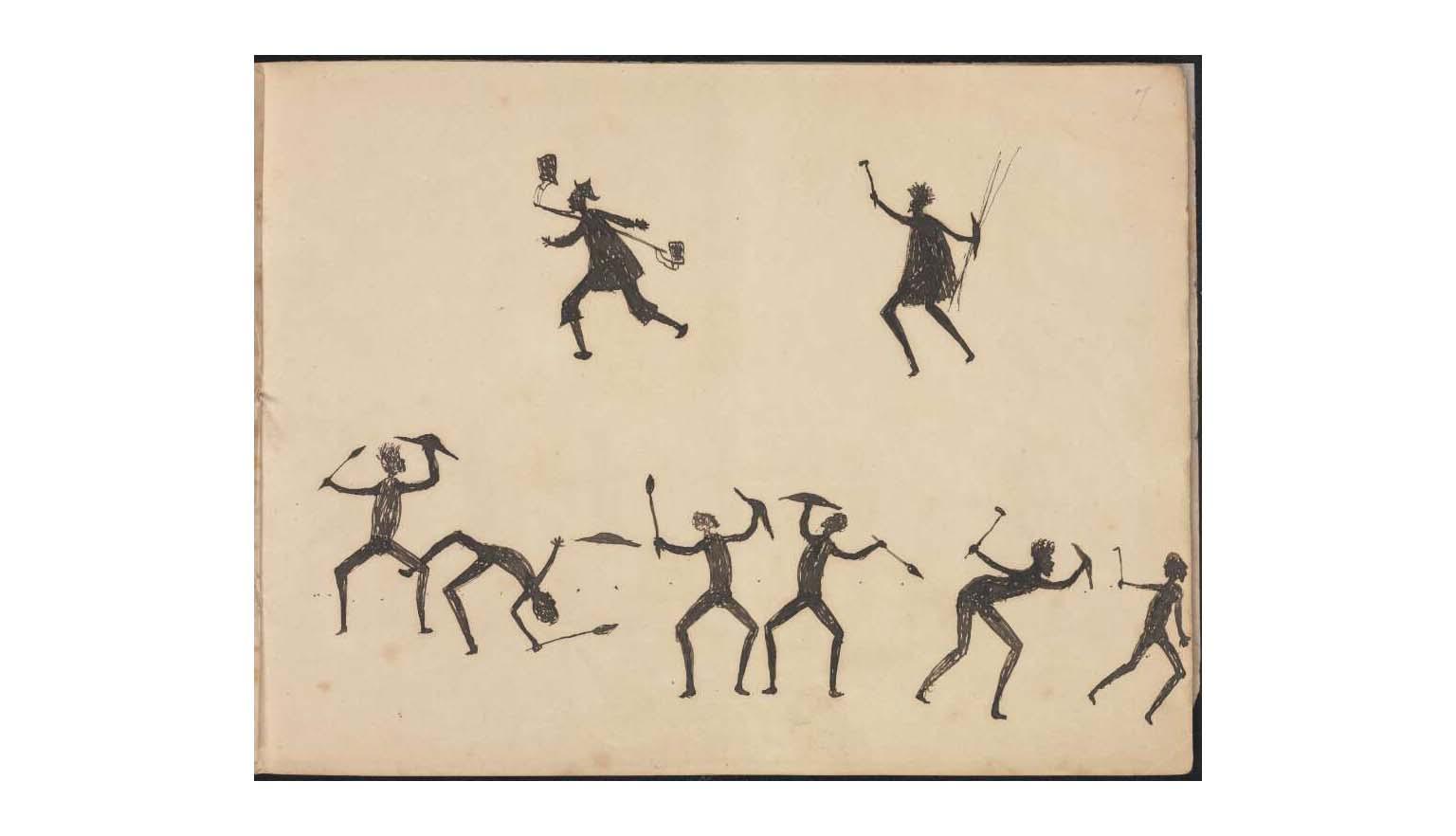

Never ceded

No European Nation has a right to occupy any part of their country, or settle among them without their voluntary consent. Conquest over such people can give no just title; because they could never be the Aggressors.

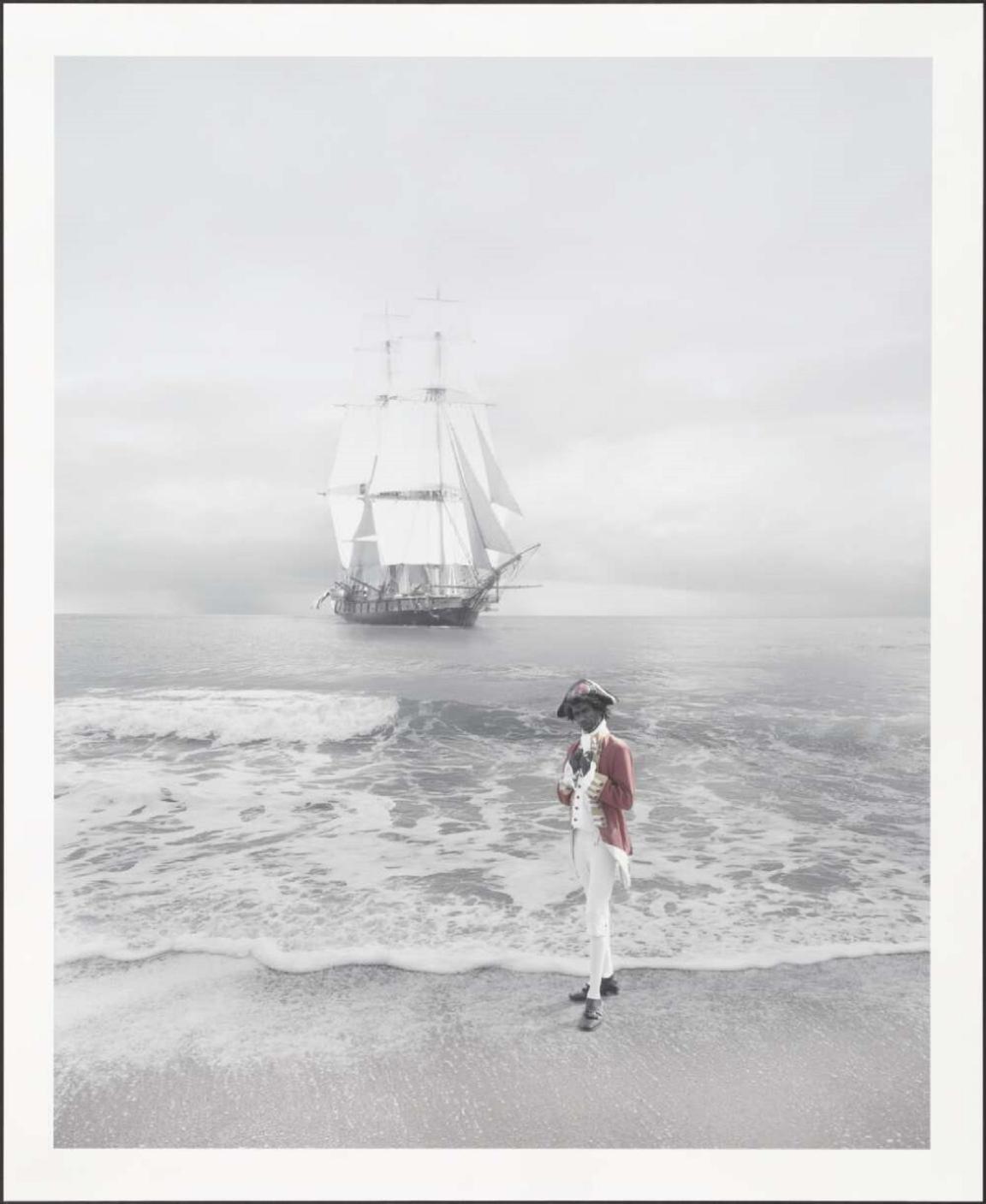

Michael Cook, Undiscovered #4, 2010, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-708299938

Michael Cook, Undiscovered #4, 2010, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-708299938

Hints Offered to the Consideration of Captain Cook by James Douglas, 14th Earl of Morton, President of the Royal Society, 10 August 1768, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-222969577

The advice provided to Commander James Cook as part of the preparations for the voyage of HMB Endeavour was clear: he was not to claim any land without the consent of the original inhabitants.

Cook did not follow this advice. On 22 August 1770, despite being fully aware it was inhabited, he claimed the east coast of Australia in the name of King George III. Eighteen years later, the British government established a convict settlement on Gadigal Country, signalling the beginning of the colonisation of Australia.

First Australians have lived on the Australian continent for more than 65,000 years. They did not cede the land that the British claimed, and they continue to assert their sovereignty.

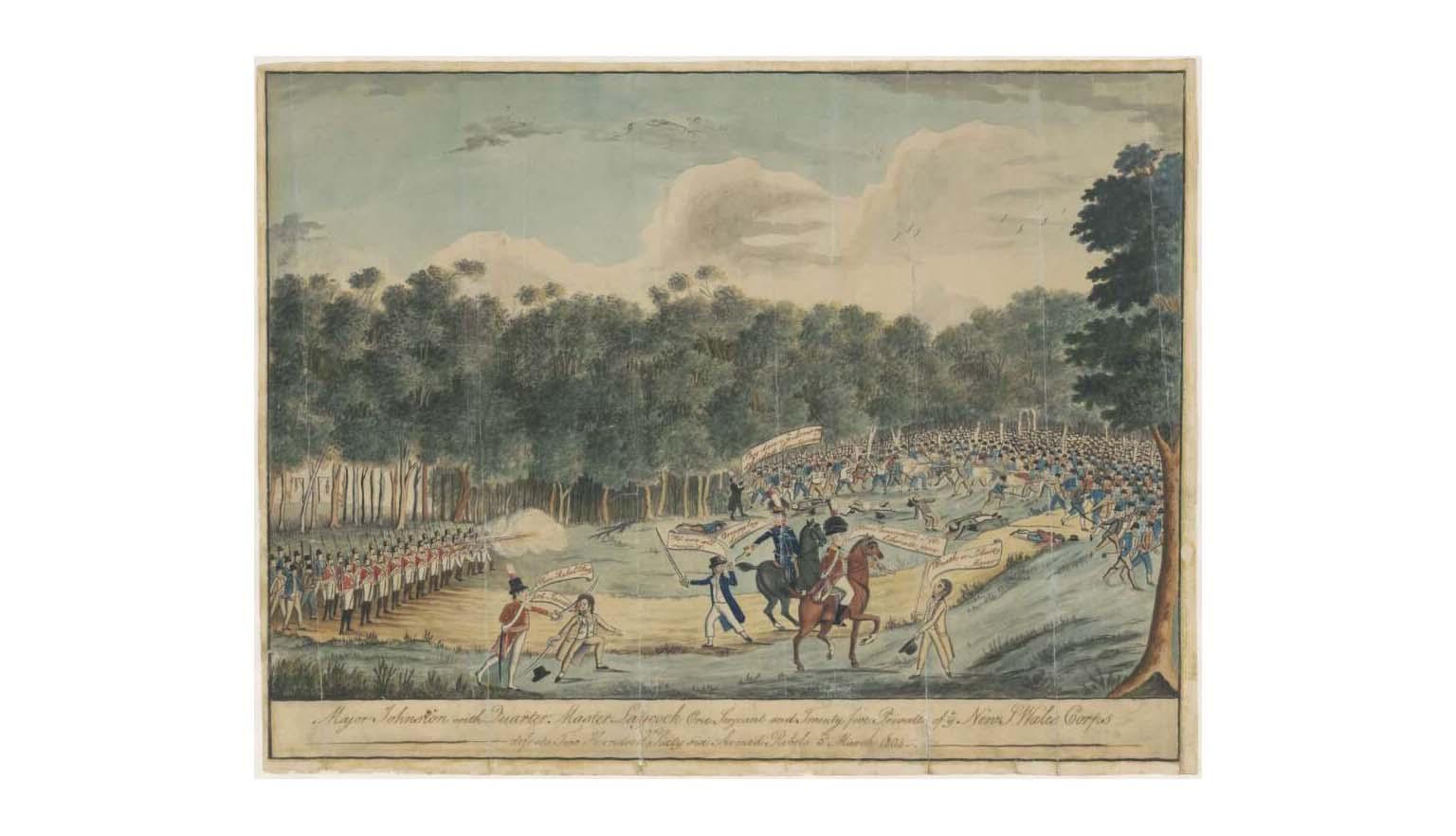

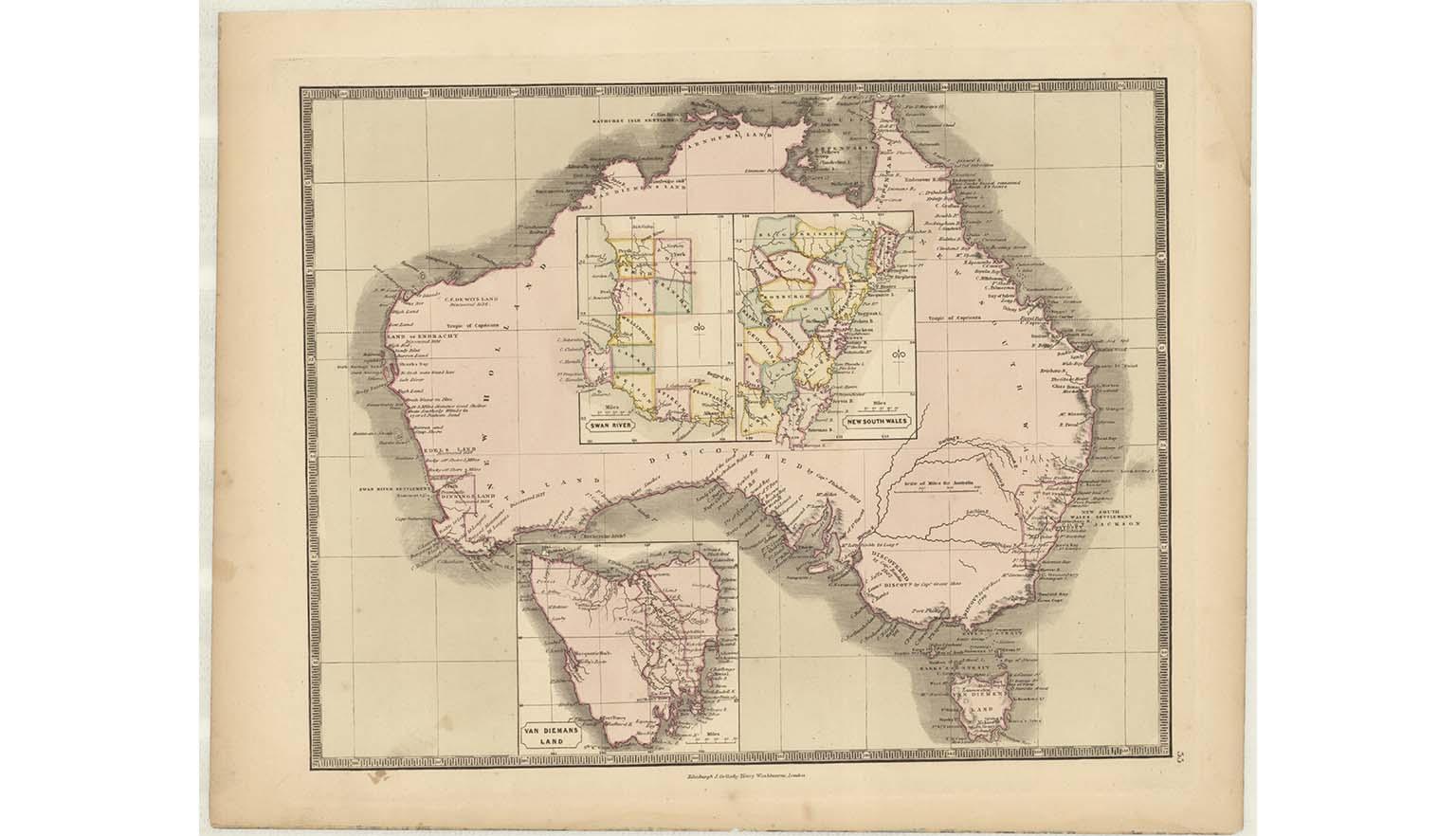

The colonies

The arrival of the First Fleet on Gadigal land at Sydney Cove in 1788 brought around 1,400 convicts, sailors, soldiers and administrators to Australia.

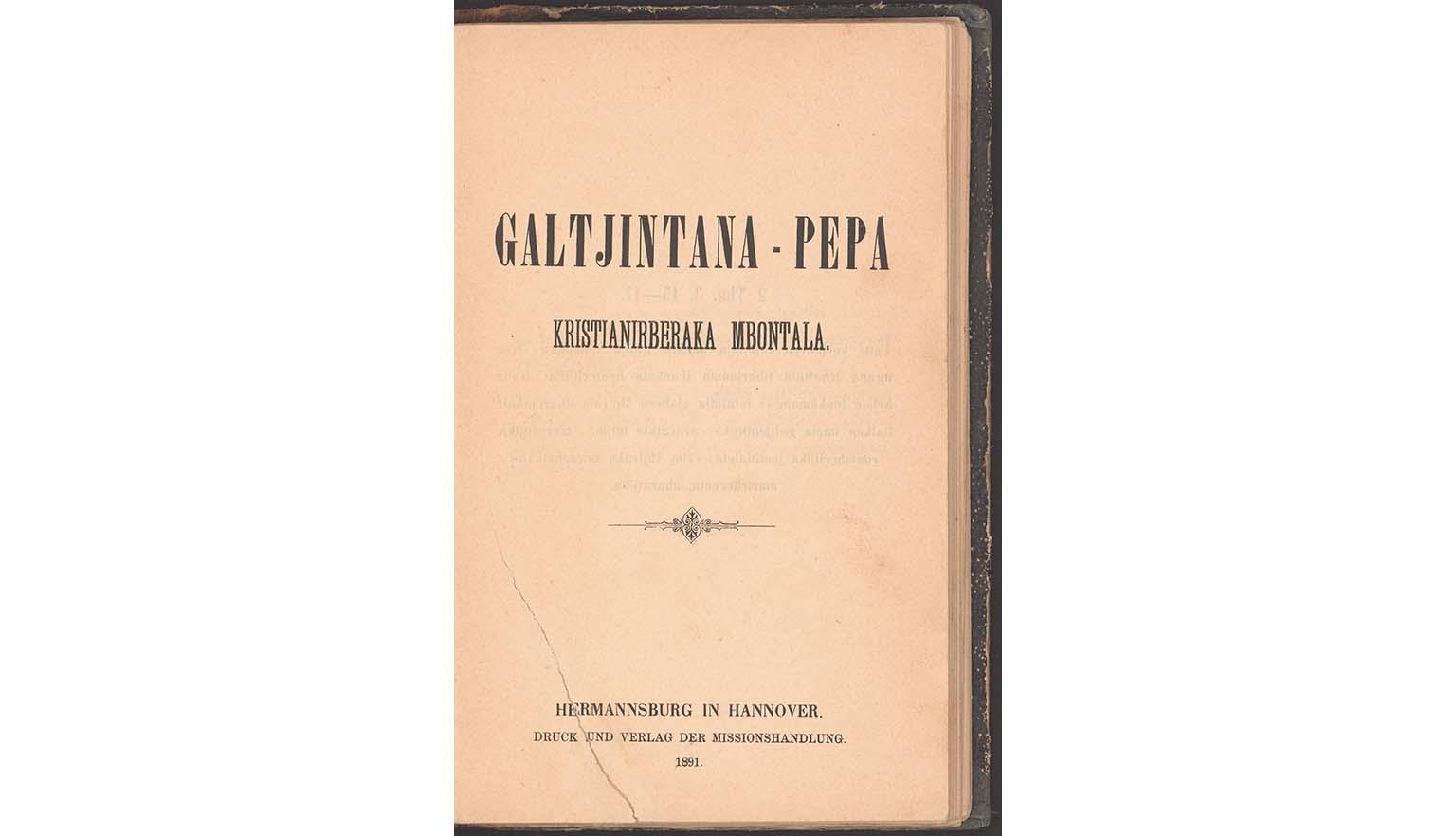

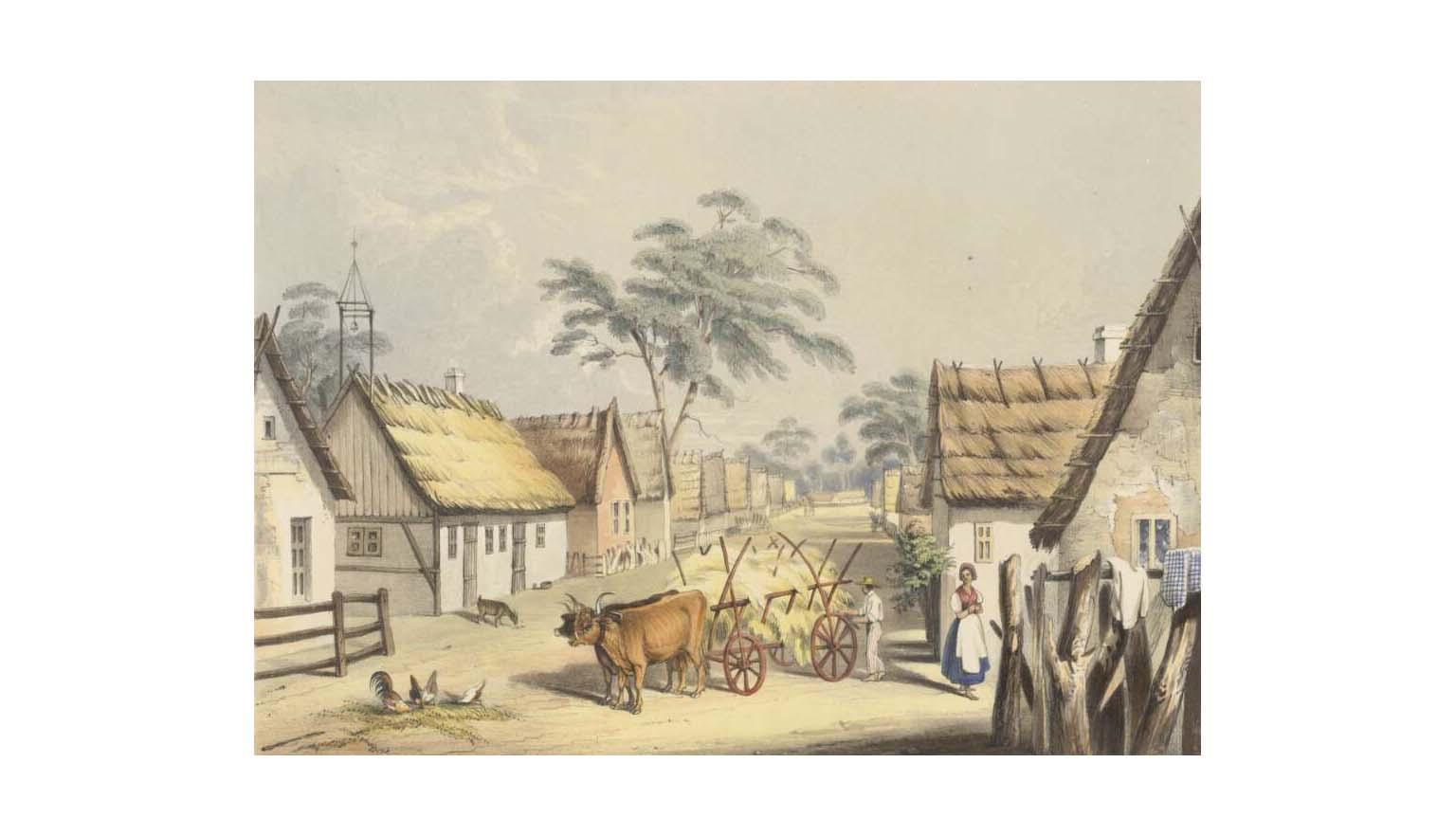

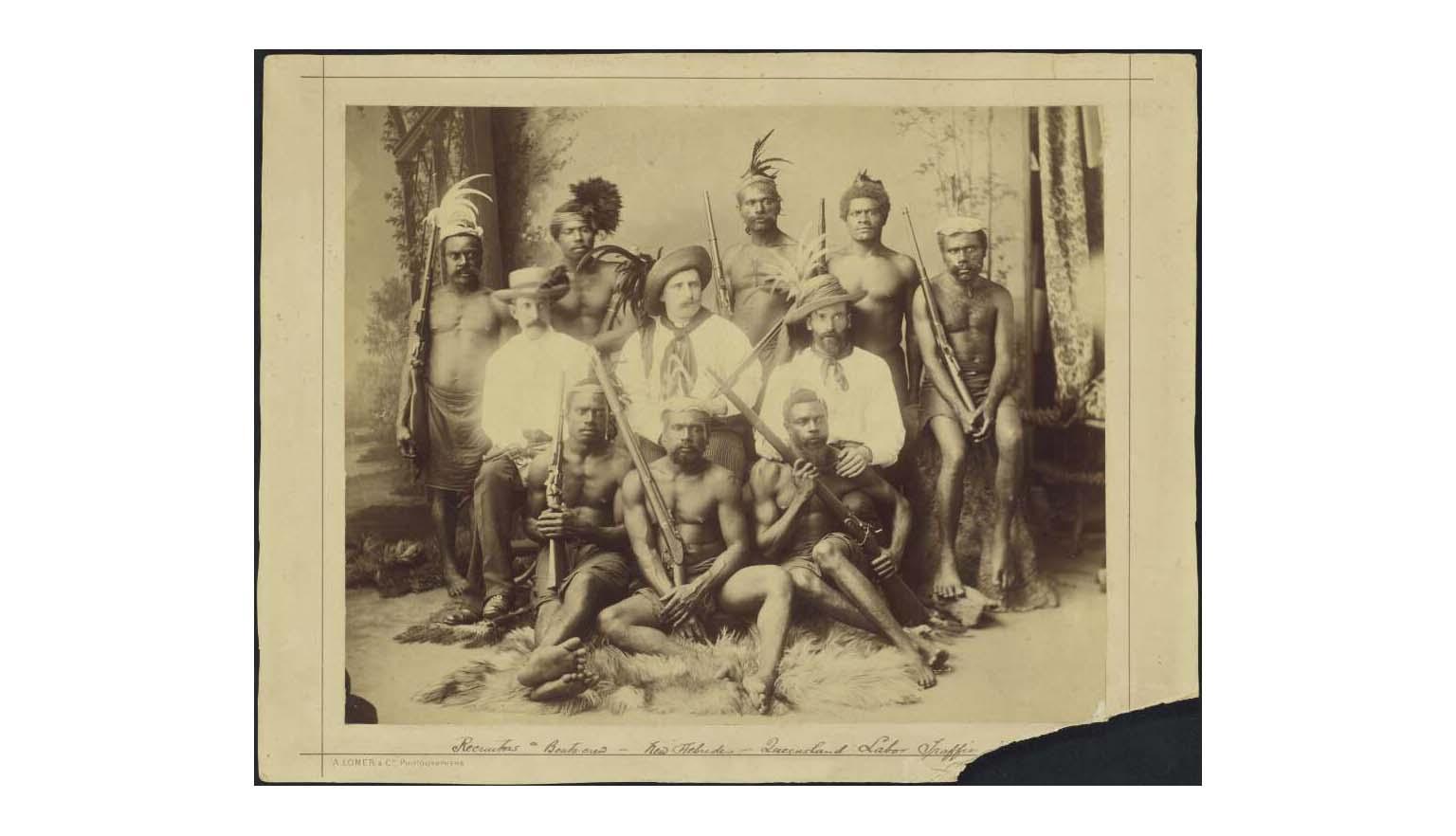

Over the next 100 years the British occupied more land, establishing settlements and dispossessing Traditional Owners. What started as a series of precarious British outposts eventually grew to become six self-governing colonies which claimed the entire continent. These colonies competed for migrants from across the British Empire.

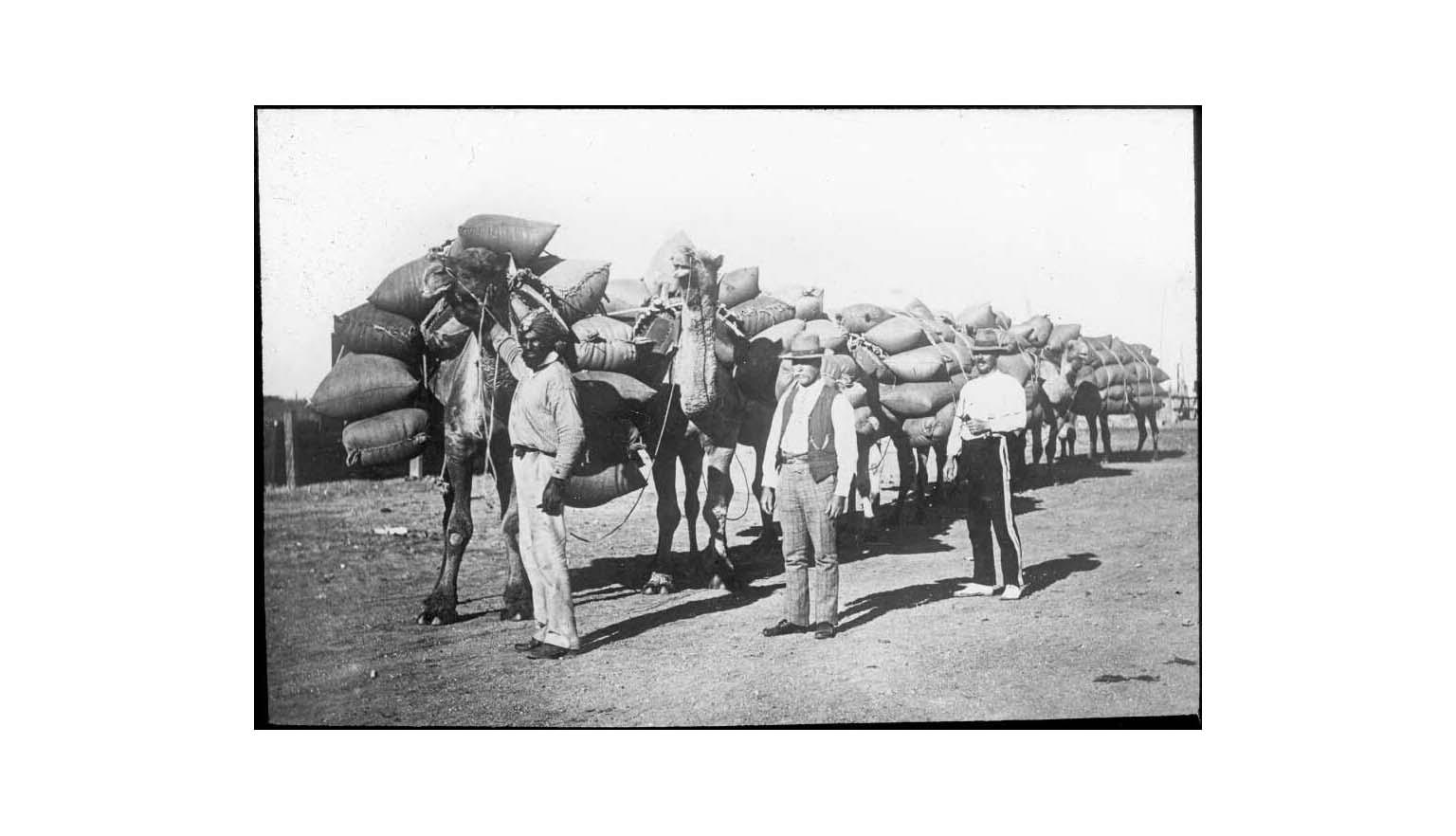

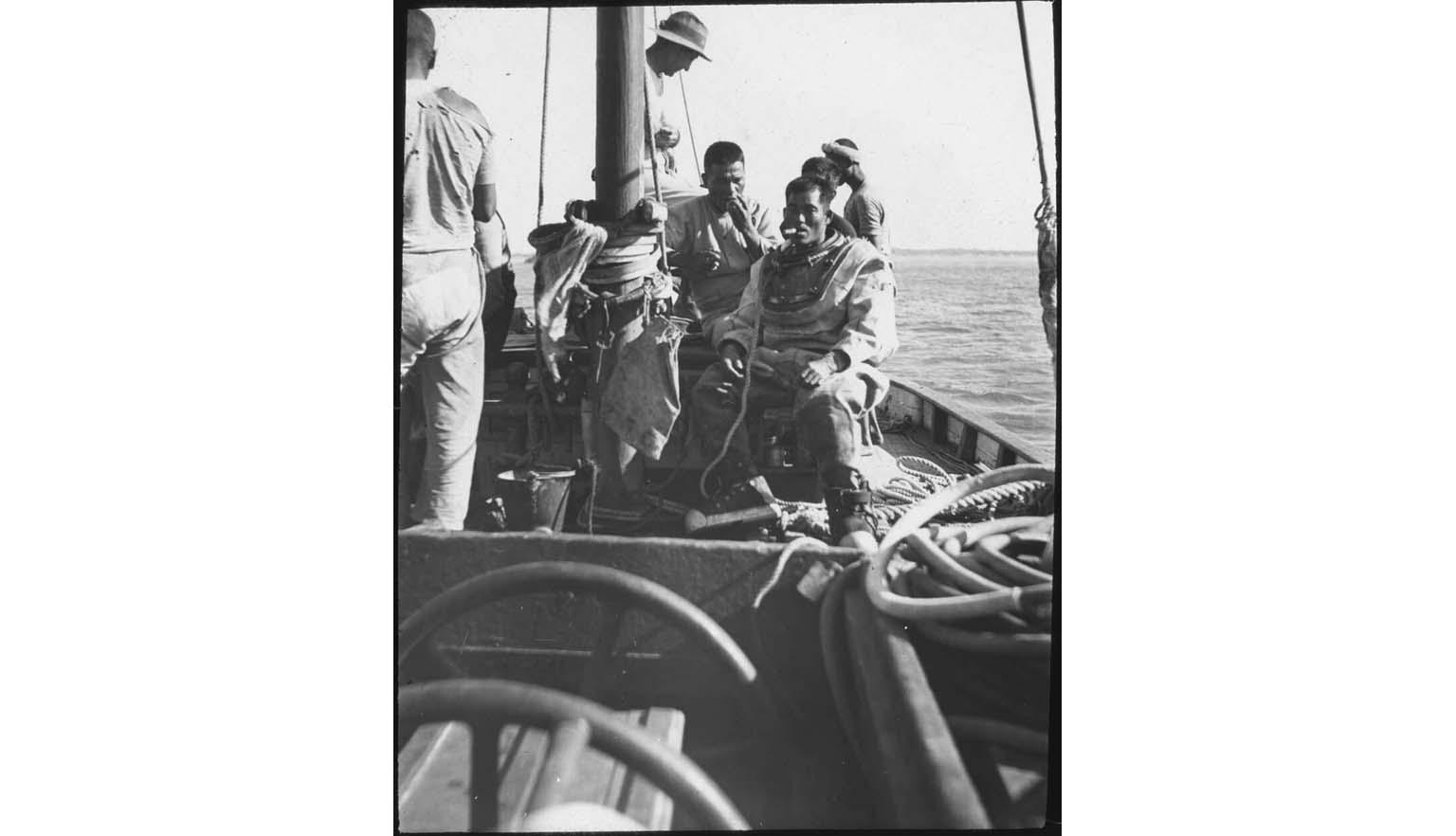

Migrants also came from Europe, the United States, China, South Asia and the Pacific. By the 1880s, Australia’s population exceeded 2.25 million people. Over the same period, it is estimated that the Indigenous population fell from approximately half a million to less than 200,000.

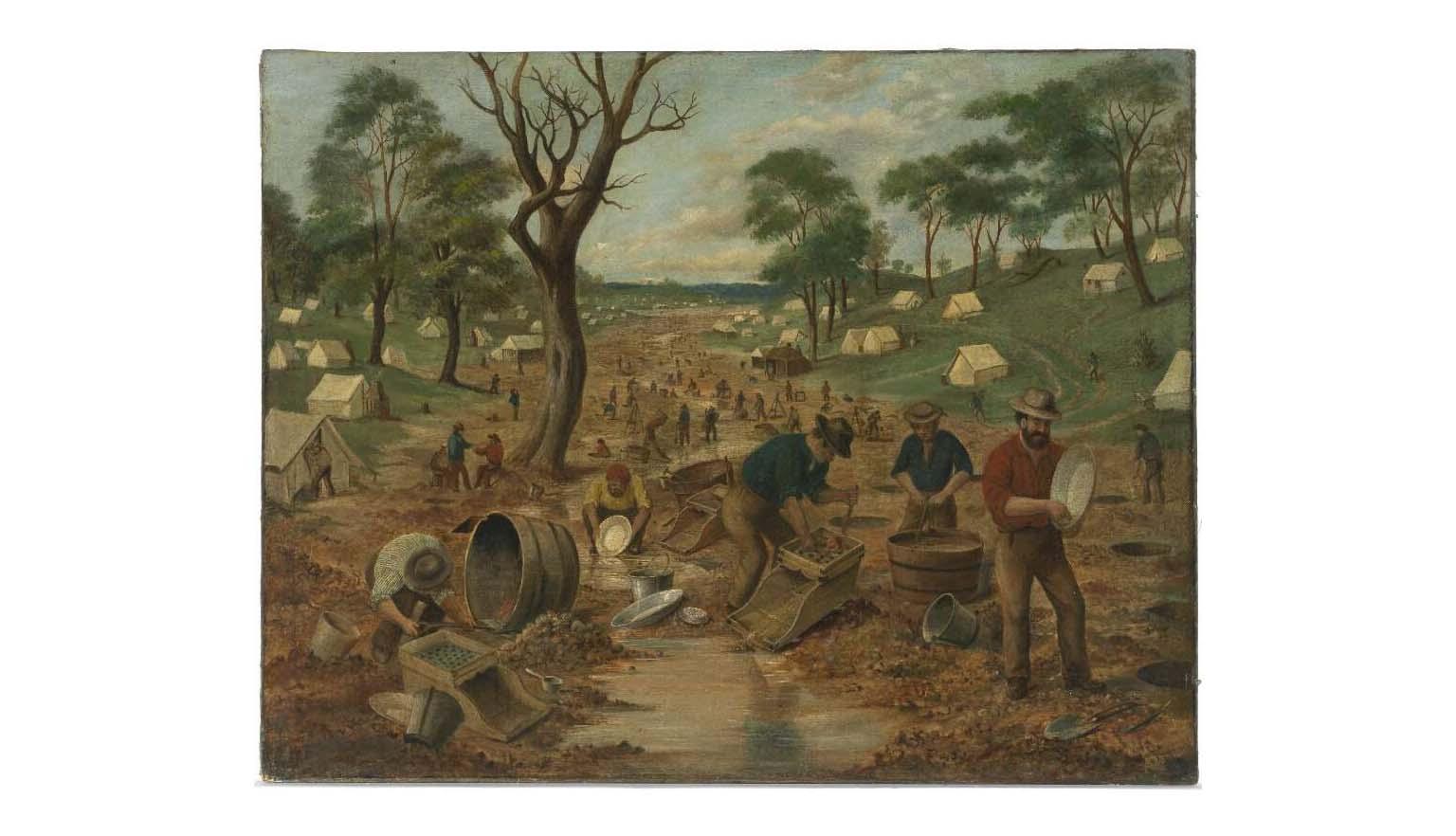

Gold and exploration

The discovery of gold at Ophir, New South Wales, and at Clunes, Victoria, in 1851 marked the beginning of Australia’s goldrushes.

Migrants from all over the world brought new skills and professions, changing convict colonies into progressive cities. In response to racial conflict, colonial governments implemented the first wave of anti-Chinese legislation in Victoria (1855), South Australia (1857) and New South Wales (1861). These laws were repealed by 1867 after sustained resistance from Chinese people and their European allies.

European explorers made their way across the continent in the 1860s, opening up land for pastoral and agricultural industries. However, in doing so, they hastened Indigenous dispossession and environmental change.

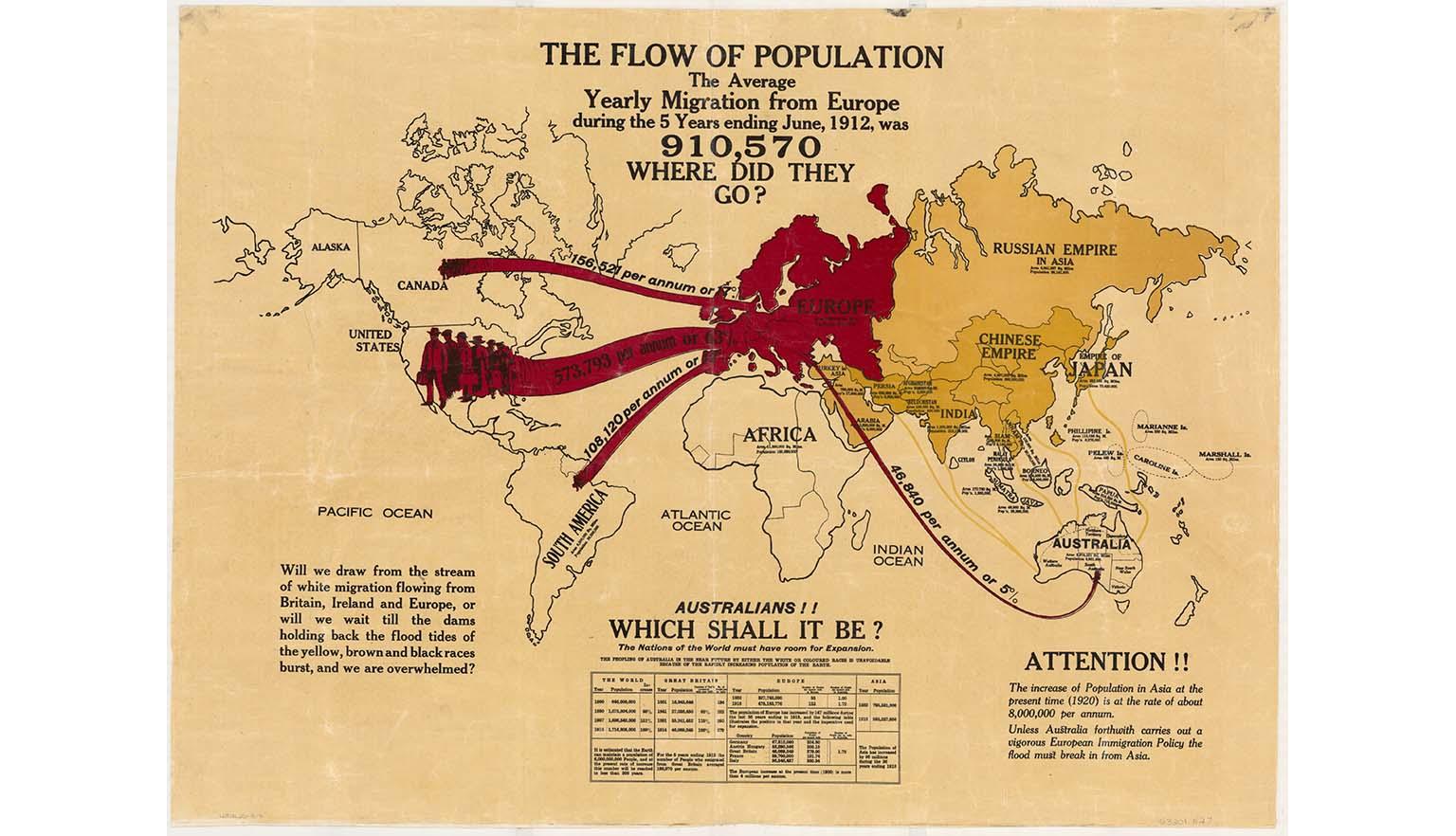

An outpost of the British race

The lead-up to Federation in 1901 centred around desire for a ‘white’ national identity. British political values, including the rights of the individual, personal liberty and, private property, a broadly free market economy, state-owned infrastructure, democratic institutions and constitutional government, informed the creation of the Australian nation. These ideas were thought to be incompatible with a society containing different races with different standards of living.

The 1901 Constitution gave the federal parliament powers to make laws regarding ‘people of any race’, except Aboriginal people, and issues such as ‘immigration and emigration’, ‘naturalisation and aliens’ and the ‘influx of criminals’, all of which underpinned the laws that would make up the White Australia policy.

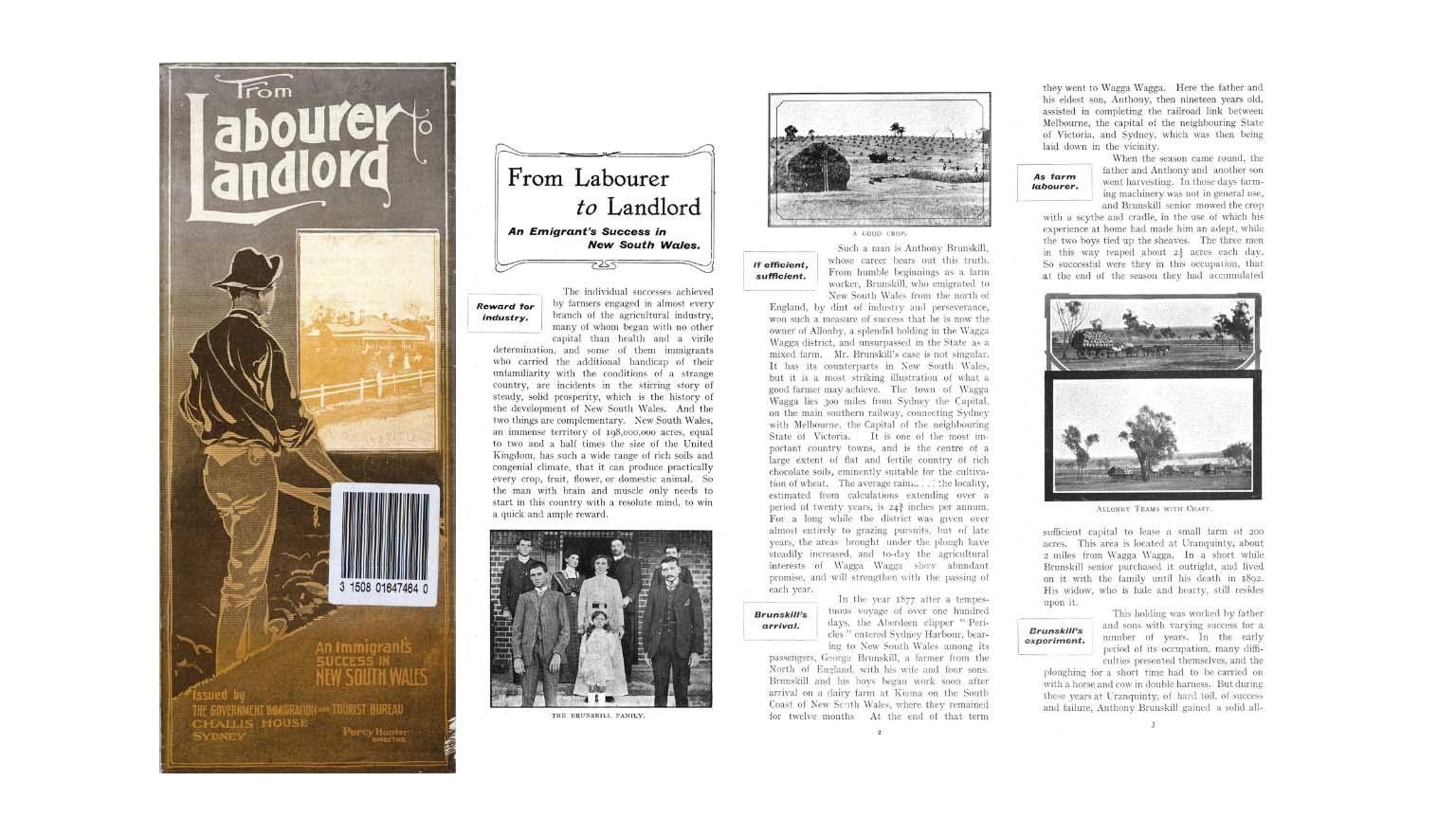

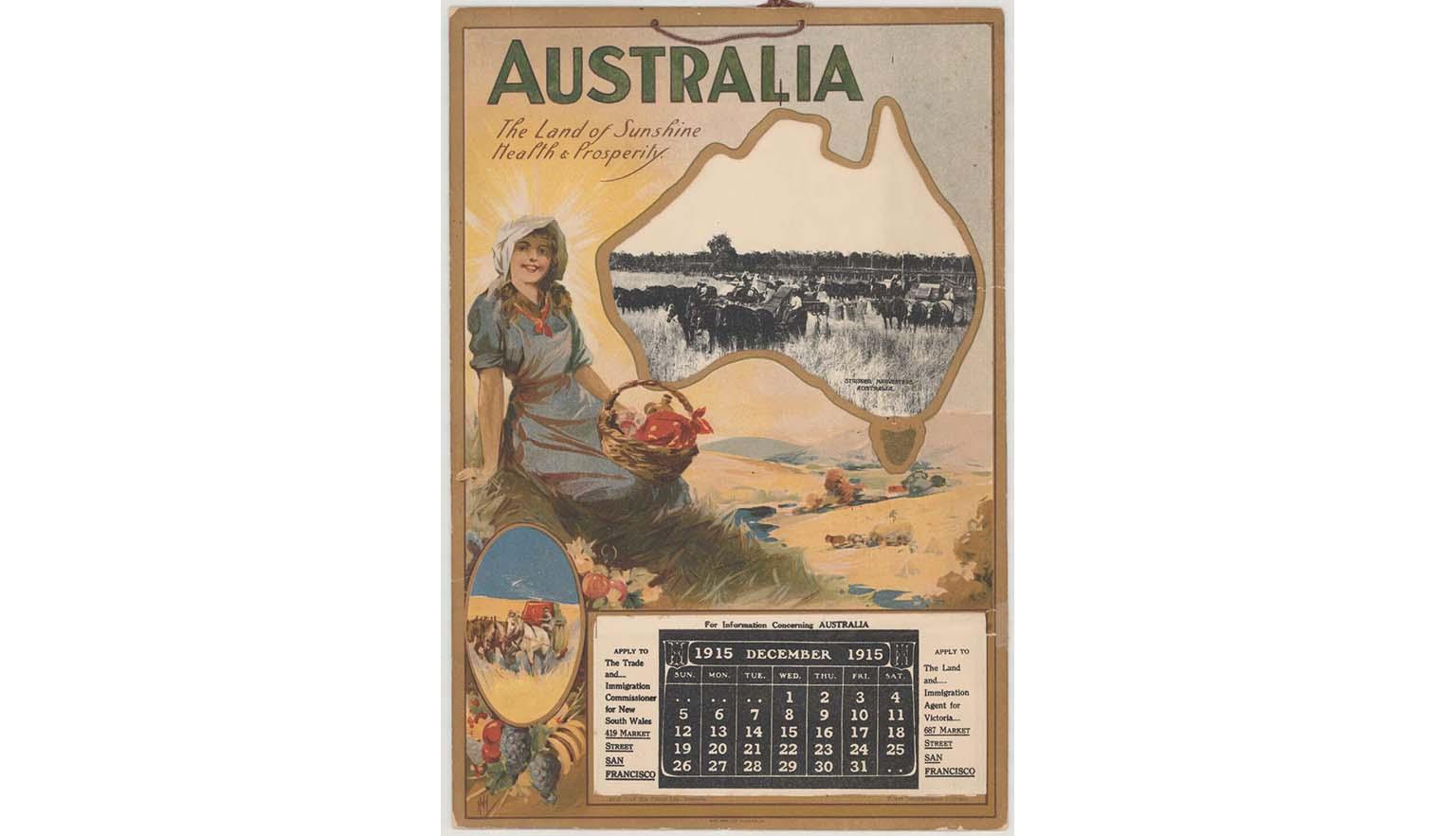

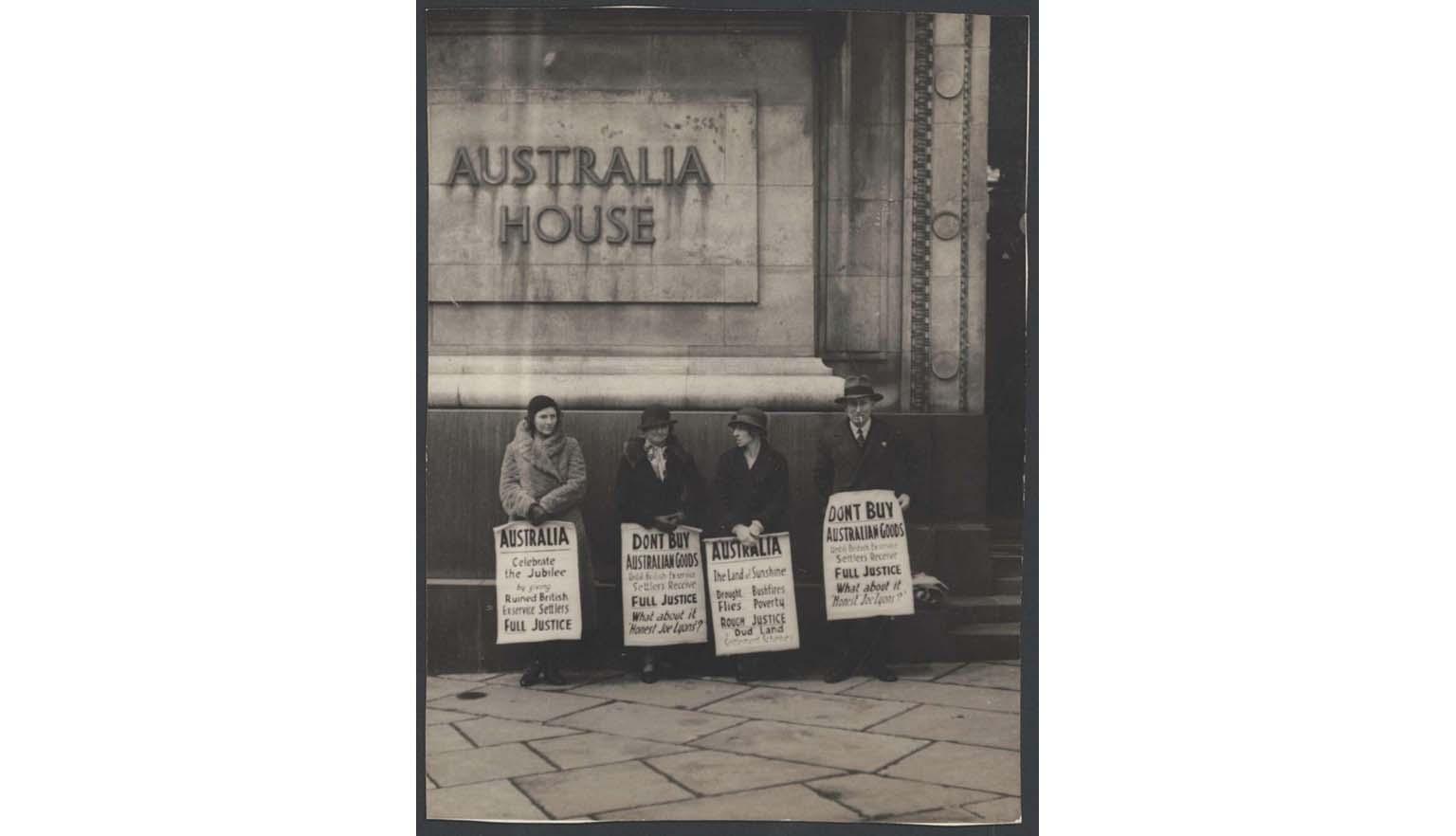

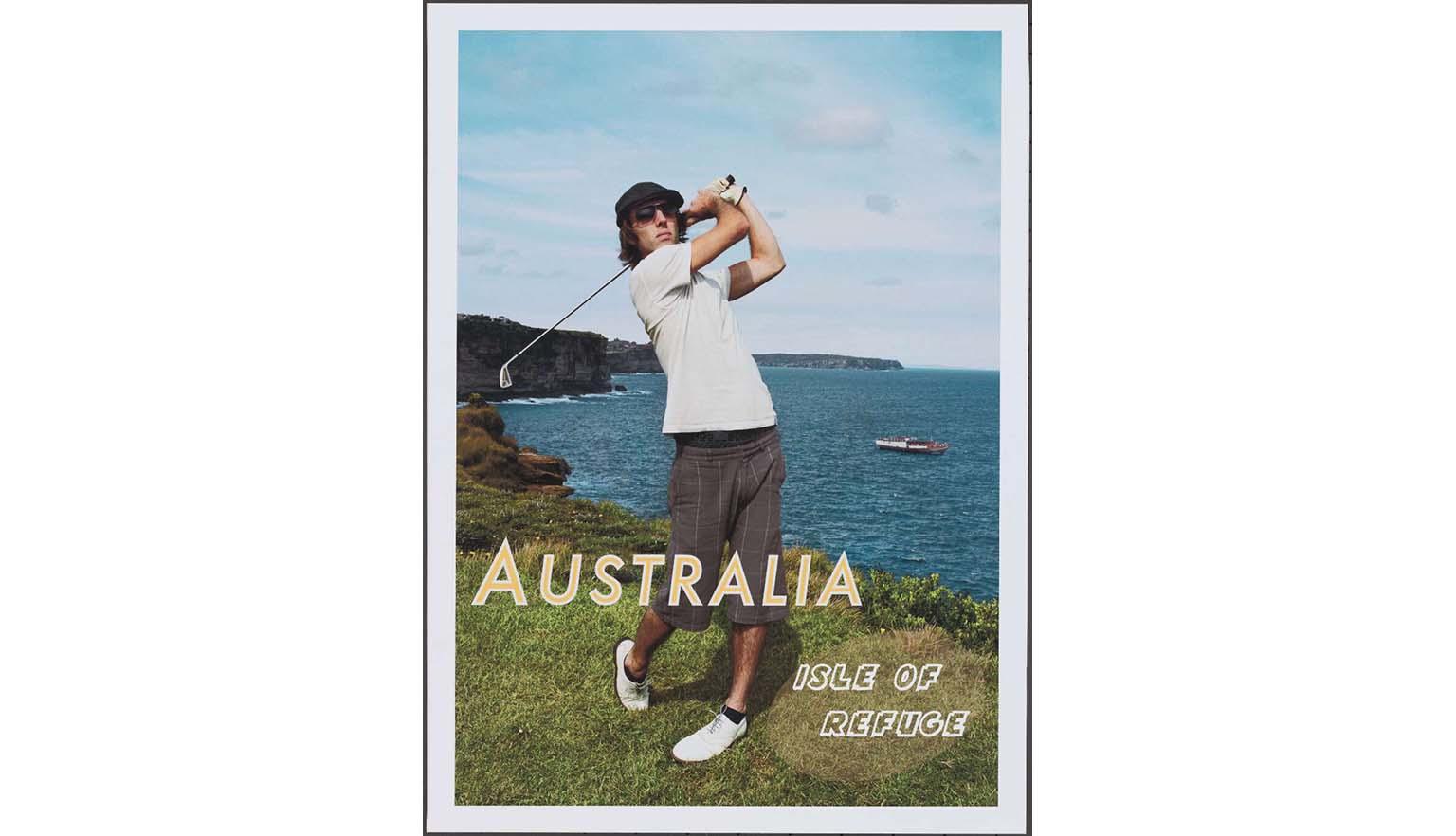

Selling a dream

After Federation in 1901 competition for British migrants was fierce. In addition to the Commonwealth’s promotion of migration programs, state governments also ran their own advertising campaigns, promoting the virtues of moving to particular regions in Australia. Shipping companies such as the Commonwealth Line and P&O advertised cruises to Australia. The imagery used in the advertising material focused on the economic opportunities and healthy lifestyle available for migrants. Australia was often depicted as an agricultural paradise populated by robust ‘white’ farmers.

The First World War temporarily halted the flow of migrants to Australia, but it soon regathered pace in the 1920s. Britain was again targeted as a potential source of workers, particularly farmers and domestic servants.

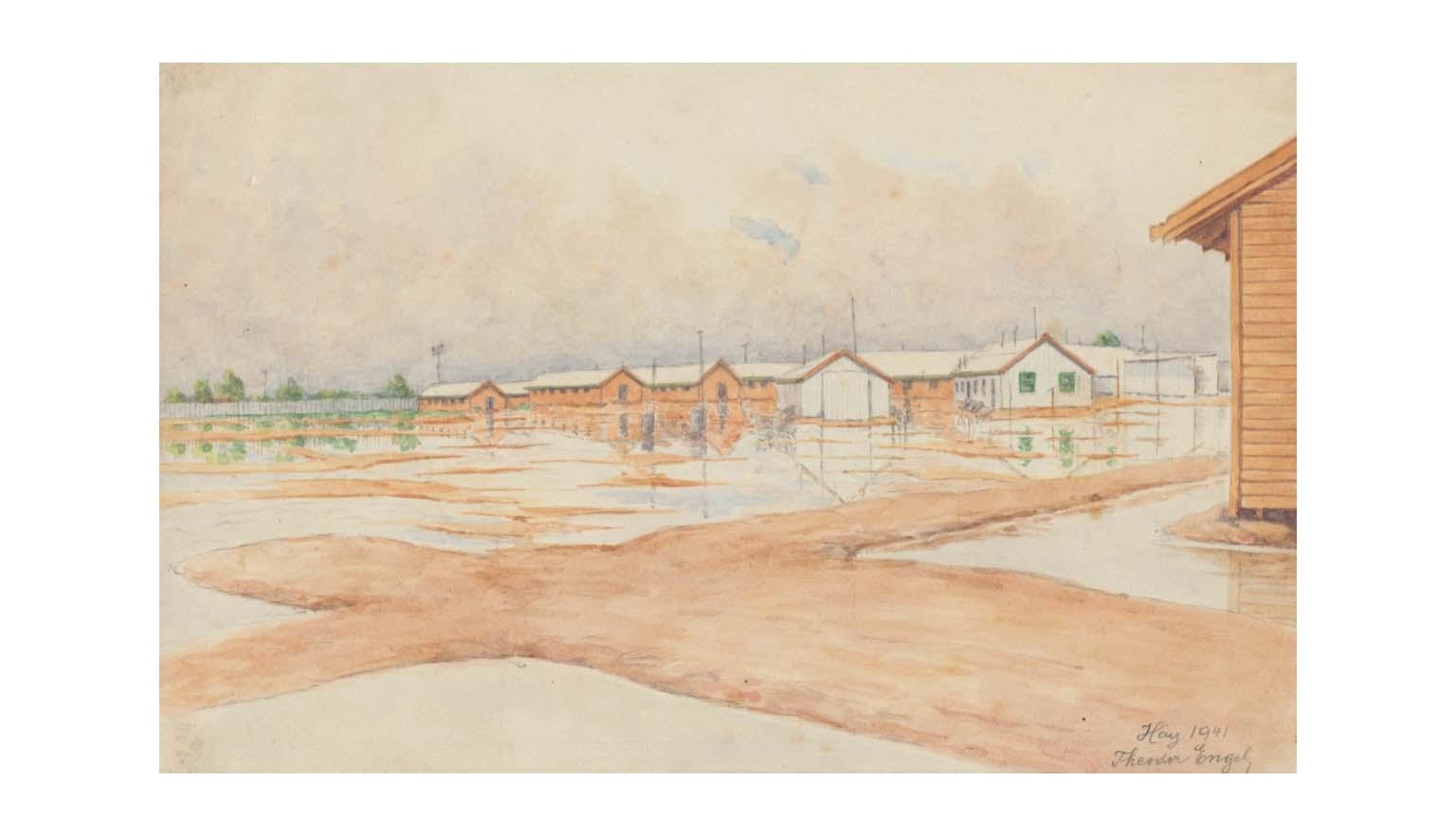

Becoming Australian

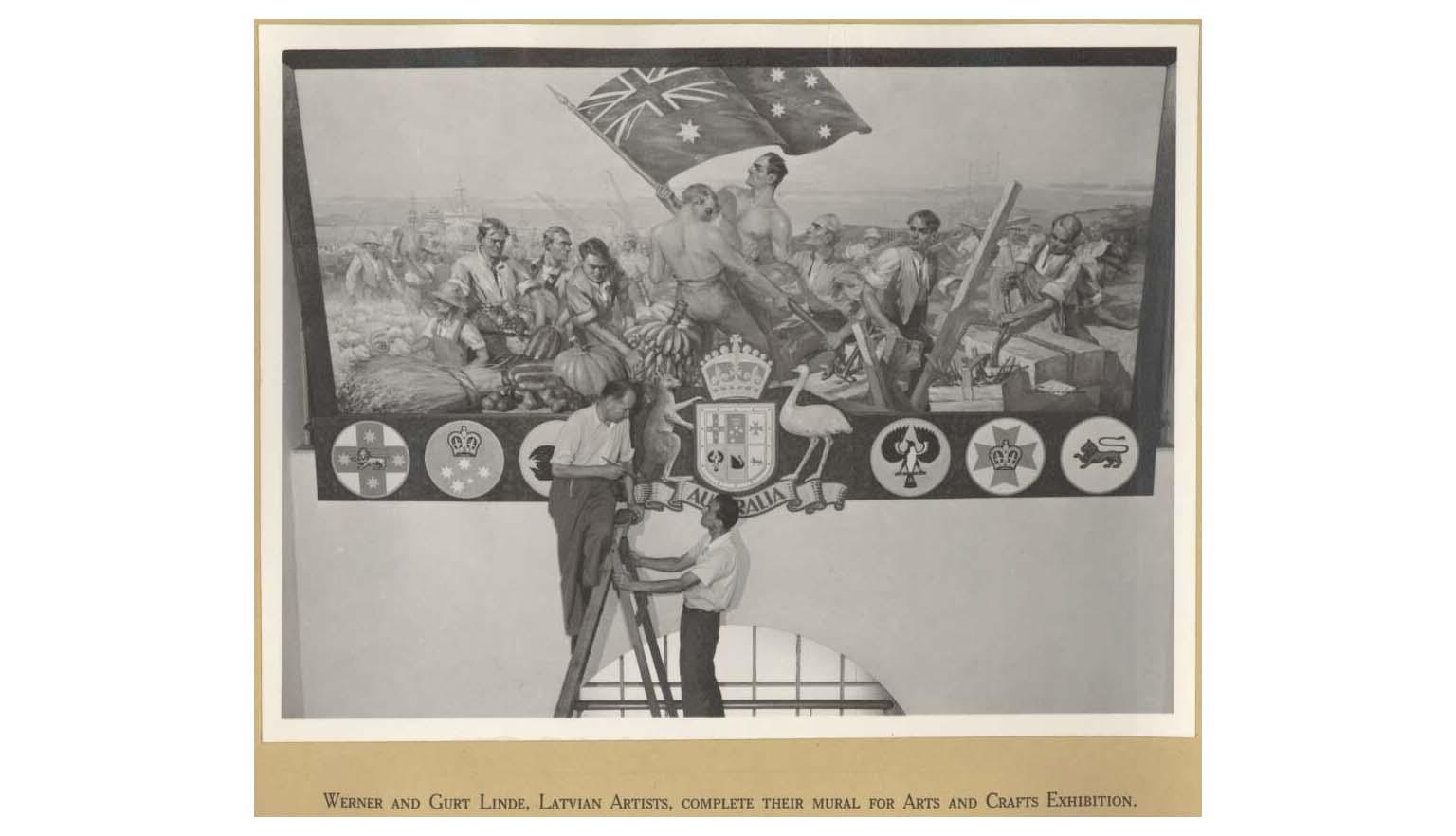

During the later years of the Second World War, the Australian Government began planning for an expanded immigration program. A rapidly growing population was seen as the best way to defend a nation that had feared a Japanese invasion during the war. A target of 70,000 migrants a year was set, and while the emphasis was on British migrants, the government began an advertising campaign to encourage the Australian public to accept a wider range of European migrants.

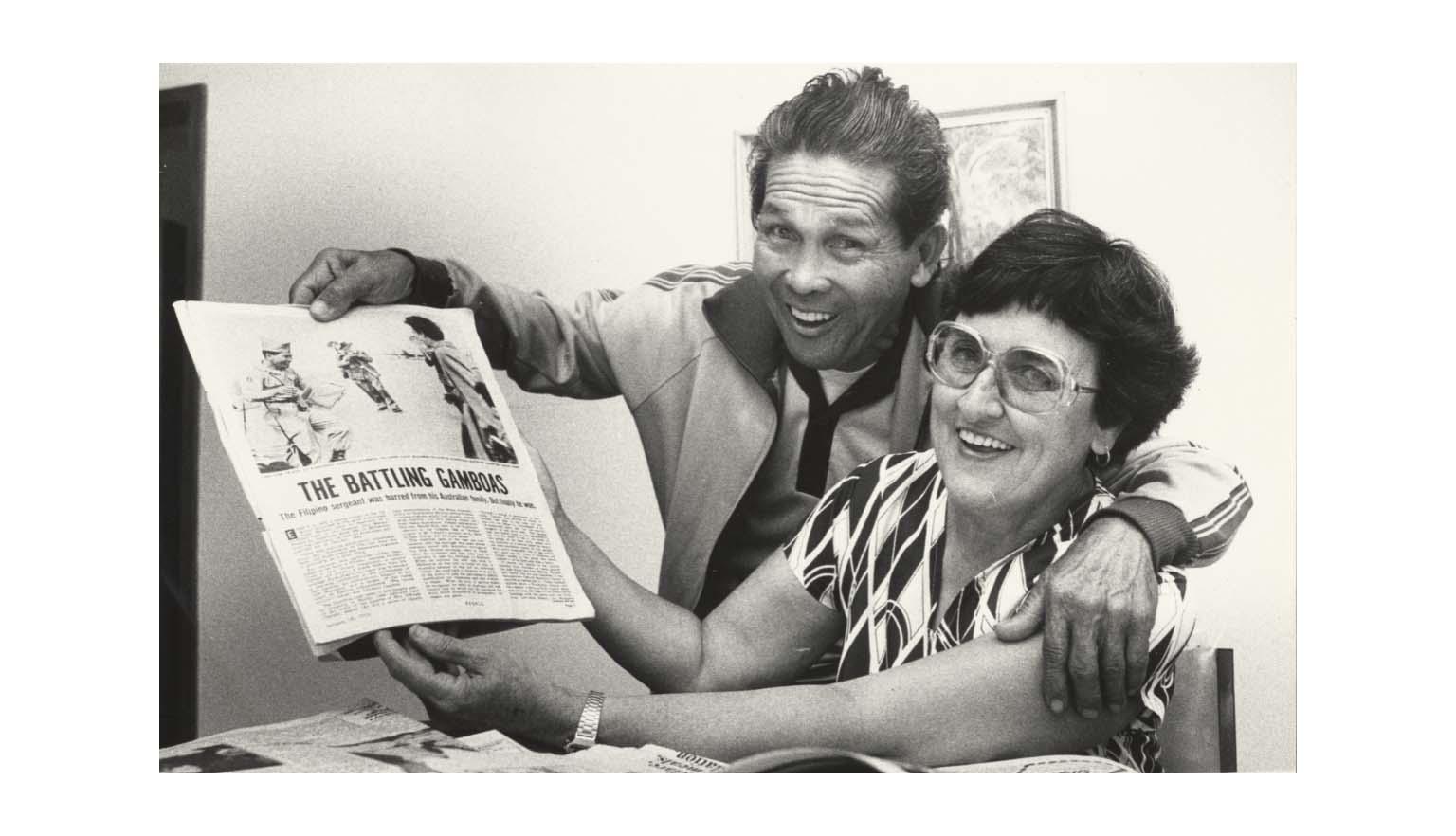

All self-governing nations of the Commonwealth agreed that each nation could define its own citizenship in 1947. The Australian Nationality and Citizenship Act 1948 was used as an incentive to encourage non-British migrants to assimilate so they could be rewarded with full citizenship. The White Australia policy began to be dismantled, starting in 1958 when the infamous dictation test was replaced by a visa system. From 1966 potential migrants were assessed by their qualifications and suitability to settle rather than by their race or nationality. In 1973 further changes were made, and migrants became eligible to apply for citizenship after three years of residence, regardless of race.

In the 1970s, Australia moved beyond assimilationist policies to a new vision of a multicultural Australia. The country’s migrant intake was becoming more diverse than it had ever been.

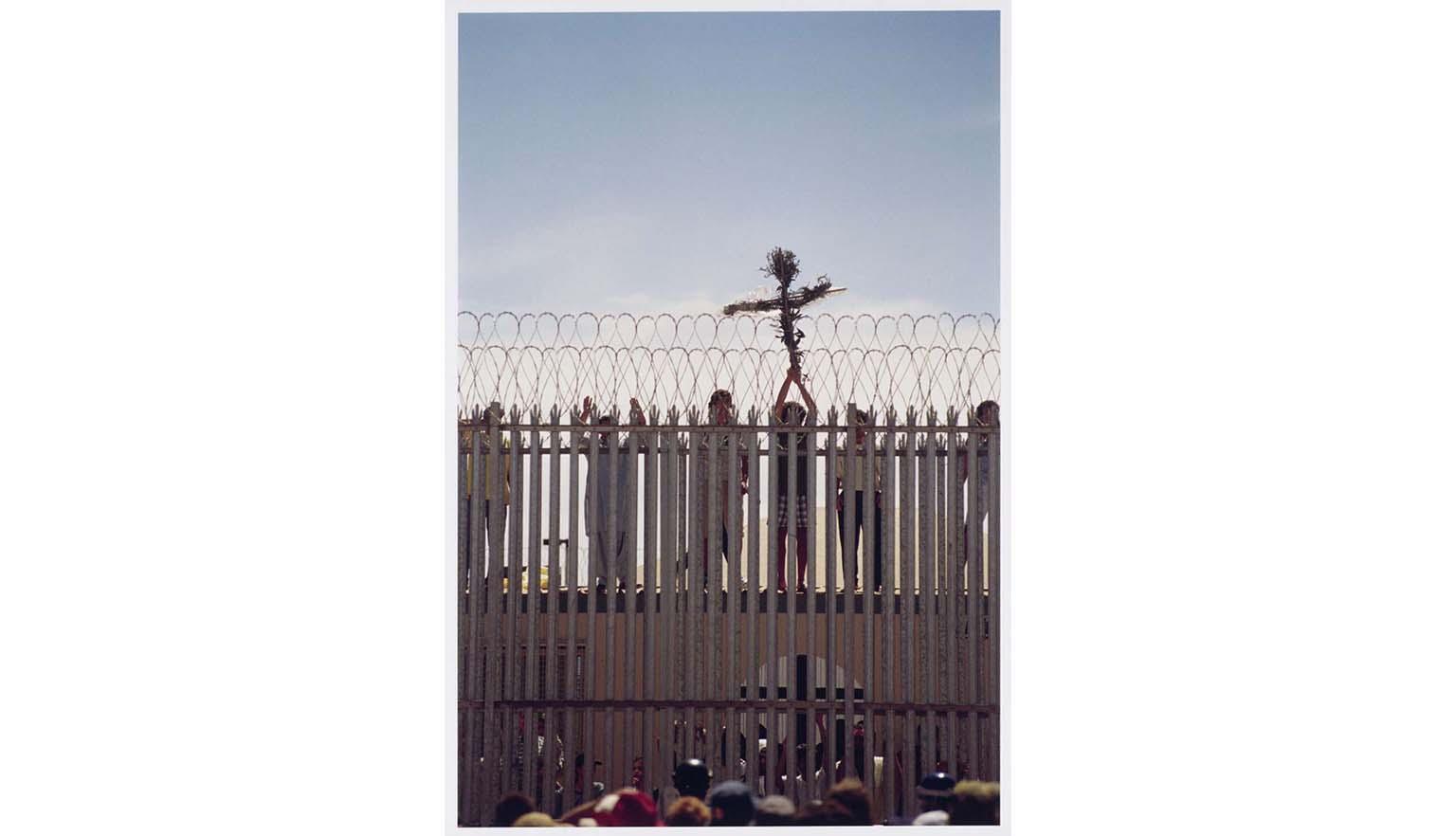

Refugees

Refugees from Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia came to Australia after the Vietnam War ended in 1975, many by boat. Political unrest and conflict in South America and the Middle East also encouraged refugees to seek protection in Australia. The suppression of the ‘Tiananmen Square’ democracy protestors in 1989 saw many Chinese students apply for residency in Australia. The series of wars in the former state of Yugoslavia in the 1990s led to more refugees applying to come. Australia’s humanitarian program continues today, with refugees arriving from countries such as Sudan, Eritrea, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Myanmar and Afghanistan.

In the 1970s and 1980s, migration became the focus of fierce political debate in Australia. Both Labor and Coalition governments shifted the focus away from assisted migration to schemes specifically designed to attract skilled migrants to fill labour and skill shortages. In 1989, after an eight-year gap, boats carrying asylum seekers began to arrive again. The government responded by introducing mandatory deportation of illegal immigrants, followed in 1992 by mandatory detention of any asylum seekers arriving by boat.

Our collecting

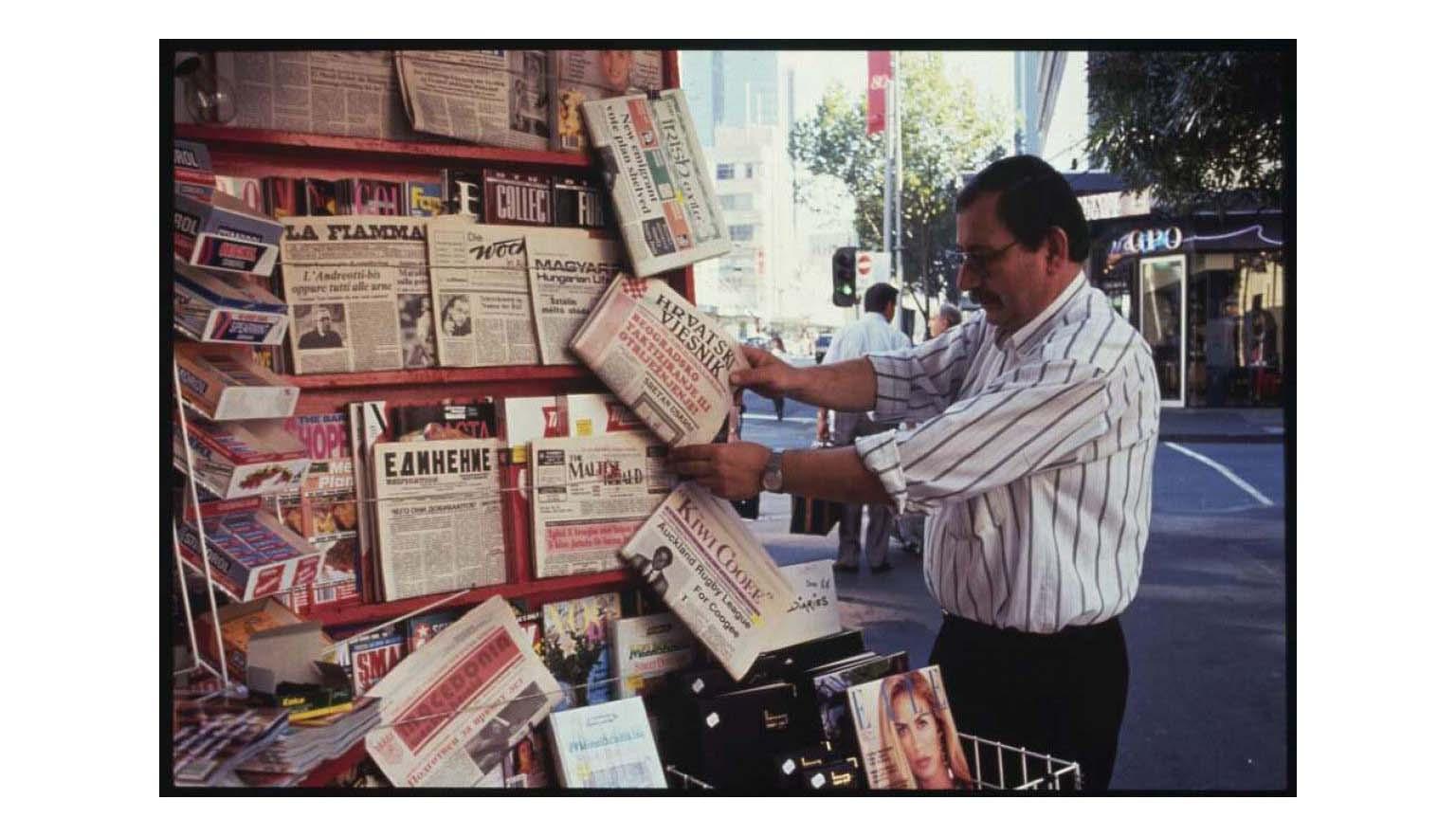

Cultural diversity is celebrated in contemporary Australia. However, issues surrounding migration, border control, migrant workers’ rights and First Nations sovereignty remain controversial.

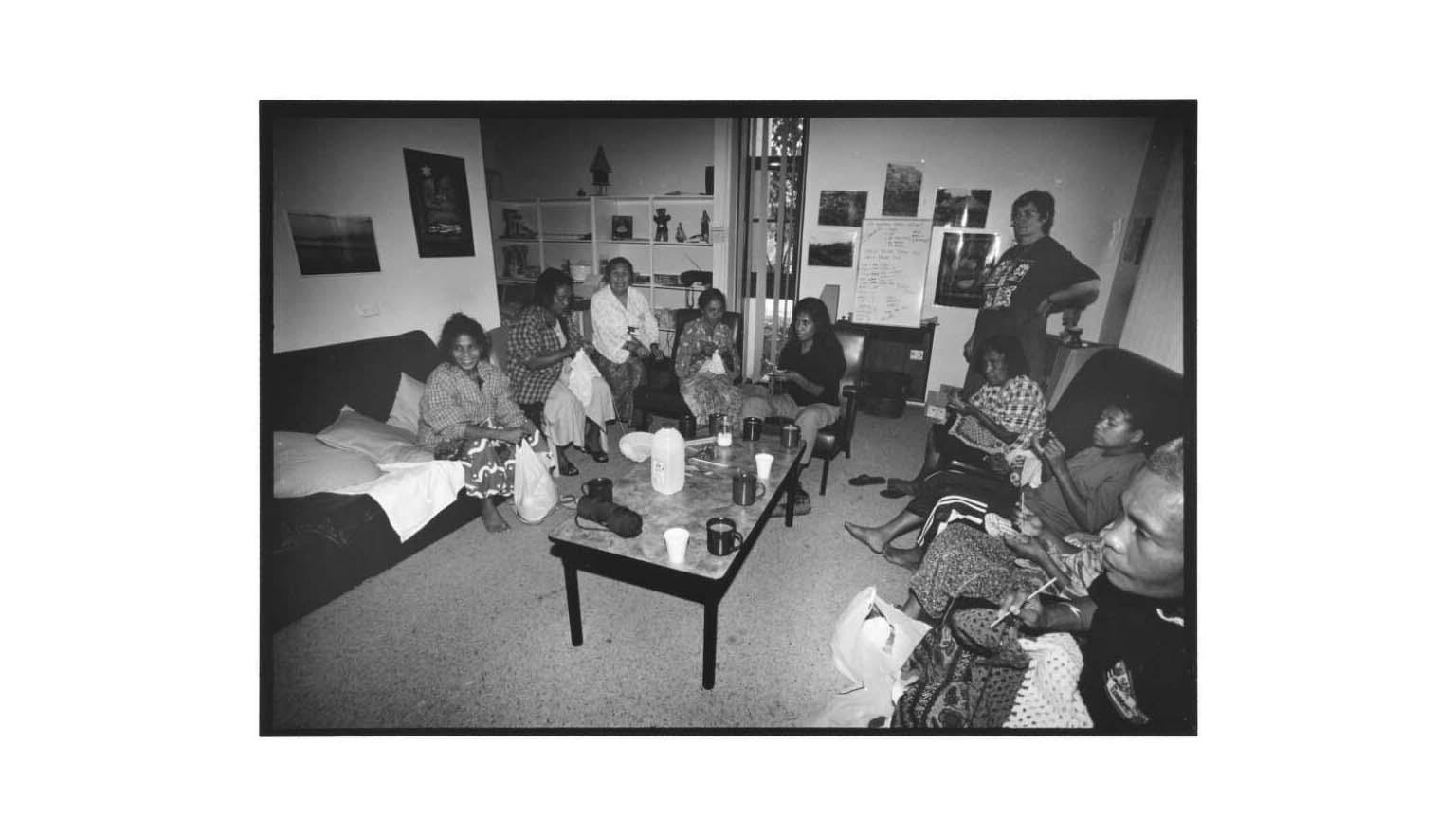

Artistic and first-person perspectives on these topics are represented in our collection. We work with culturally and linguistically diverse communities to create a lasting record of their experiences in Australia. Targeted collecting projects with Chinese and Fijian Australians between 2021 and 2023 have increased the representation of these communities in the collection.

A broad range of material is collected, including newspapers and oral history interviews. These resources are freely available for all to use when researching their own migrant family histories.

Newspapers

Browse these newspapers online:

- Chinese Republic News

- Chinese Times

- Chung Wah Newsletter

- The English and Chinese Advertiser

- The Chinese Australian Herald

- Murhun

- Tung Wah News

- Der Australische Spiegel

- Australische Zeitung

- Echo

- Japanese Perth Times

- The Jewish Post

- The Australian Hebrew Times

- Le Courrier Australien

- Meie kodu

- Mudu pstoge

- Norden

- Sunday times edizione italiana

- L'Italo Australiano

- The Irish exile and freedom's advocate

- Vesnik

- Vil'na dumka

- Dutch Australian Weekly

Oral histories

Our Oral History and Folklore collection dates back to the 1950’s and includes a rich and diverse collection of interviews and recordings. There are hundreds of individual interviews of people who have migrated to Australia as well as from immigration officials, refugee advocates and former Ministers of Immigration.

You can listen to a selection of these interviews here.

Hopes and Fears: Oral histories

Elba Cruz-Zavalla: …the following weekend we decide with my husband and um to took the chil, ah take the children for a walk. And we went to, we walk about, you know, like two or three kilometres away from where we were, we were, or maybe a little bit more. And we found a suburb around there. And we saws an oval. And it was on a Saturday. And he ah saw people playing soccer. And we walk there and there they were. All the Latina people playing soccer. There! Oh my god, it was such a beautiful thing to... We, you know, we got there and they couldn't believe it that we were there and nobody knew about us. It was only two families, one from Argentina and one from Chile were in, in the hostel from Latin America. The others, they were all Vietnamese and English. So anyway um they got us under their wing, everybody. You know, welcome us. And they were happy to see us and very supportive. And, and this family, this Chilean family, you know, you can tell she, they were from a very were, working class. They had no politics or anything. They just got to Australia because they had opportunity to come. They um they ah took us to their house. And they were living in front ah one of those drive-in ah theatres. And they said, 'Oh come to us and spend the night with us in our house. We got a um a screen in front of us where we can see pictures and stuff.' And we had a lovely night there and we feel like home. You know, very welcome.

Hamish Sewell: So um, Everest, where would you like to start?

Everest Pitt: I guess my arrival. So I arrived here as a twenty-one-year-old. I actually celebrated my twenty-first birthday here in 1974. Um, having married, met and married my husband Ted Pitt—who was on holiday in Fiji and instead of the regular tourist item bringing back home, he brought me back home.

[laughs]

Hamish Sewell: As the ... yes. Yes, what are your first memories?

Everest Pitt: Ah, everything. The green, the vast ... how big it is, yes. Like everything is just so big. Because Fiji's small. And so the first thing I saw about this place was: oh my God, this place is so big, even the sky is so big. Just, because there's just so much space, I guess. The space. There's just massive amounts of space. Um, the people are so friendly. The people were so friendly. Just maybe over-friendly because they love to tease, yes—up here. They have this teasing thing. Which sometimes I take and other times I just like, ahh. And Ted knows, he goes, 'She's not always seeing funny. Unless you know her really well, don't.' Because I get my, I put, put up little barriers. It's like, M'mm. No, no, no, no. Not yet.

Hamish Sewell: So the kind of, the Australian sort of sense of humour.

Everest Pitt: Yes.

Hamish Sewell: Went over…

Everest Pitt: Grates, yes, with me. It's just, ohh. I'm not sure why because I love it. I do love it. It's not something I take part in. Ah, unless it's like, I've got two or three really close Aussie friends and we do it to each other all the time. So it's like close, you, to me it's like ... what is it? Permissible. Yes? But outside of it I'm hesitant. It's like, m'mm. I don't know.

Hamish Sewell: So people need to earn the license to do that.

Everest Pitt: I think. Just, just, maybe I'm just being touchy.

Hamish Sewell: Would you describe yourself as a Fijian-Australian?

Everest Pitt: Yes. Australian-Fijian. Fijian-Australian. You can turn it round. [laughs] yes.

Hamish Sewell: Well I suppose you've lived most of your life here, haven't you?

Everest Pitt: Yes. I've lived in Australia more than I lived in Fiji. I was twenty-one when I came. So the bulk of my life has been here. So I'm Australian. Um, yes.

Anna Zhu: … and can I get you to describe if you remember the first time you stepped on Australian soil. When you got off that ship.

Margaret Yung Kelly: Oh, well ...

Anna Zhu: Those experiences, I would love to hear.

Margaret Yung Kelly: Well, we were on the ship for ages and then we stopped off at Cairns or somewhere, some place where it was all stilts. All the places were on stilts. We thought ye gods, that's really strange. When we came to Sydney and what we couldn't believe, from Shanghai, Sydney in 1950 was, well, we didn't think it was a civilised city at all. We couldn't believe it. We came through and our house, of course, we stayed with auntie in Merrylands. And at that time there was no flushing toilets. No sewerage then. We had to go from the house out to the dunny at the back with the choko vines, you know. Now you can say, 'Oh yes, it's sort of fun.' But going in the middle of the night to go and go and sit on a toilet and then the manure people come in the, you know, once a week to get the cast* and take it out. We couldn't believe we had to sit on a thing with ... and, and there might be frogs in there as well. You have to check and things.

That was really, really culture shock to us. So when people would say to us, 'Oh you come from China. What do you think of Sydney?' We couldn't say anything. We said, 'Oh lovely.' To ourselves we thought what an uncivilised, where, where's the city we'll come to? We have to sit on top of a pot with all this sort of ... the manure's in there. And then of course there were not many restaurants. No French or German bakeries and, you know, there were some but we didn't have to go there. It wasn't, there were, the Chinese restaurants, the food was so awful. There were only about two in ah, Sydney in Dixon, Campbell Street that was reasonable. All the rest was just, was for the Australian palette. So it really wasn't what we were thinking of really good Chinese cuisine. Um, so we just thought, wow. You know, everything is, where are all the big buildings? I think the tallest building was Caltex House—10 storeys. And when you think of Aus-, Shanghai with the Bund with all the architecture from all over the world. We were so used to, ah, you know ah, beautiful buildings.

But of course we never said anything. We just said to everybody, 'Oh lovely, lovely.' We never like other, sometimes some, other immigrants say, always say, 'Oh yes, but we have better things at home.' We never said anything. We were grateful to be in Australia.

Michael Harvey: In hindsight, what happened was, if you look at the history of child migration um it was done for political reasons, social reasons, religious reasons. And um one of the reasons was that Britian was in, there were a lot of kids in orphanages in those times and what they did was say 'well were having a bit of a problem, lets see what we can solve, you know, what we can do regarding these kids'. So what they did, they just emptied the orphanages out, virtually I'm not saying at one hit. But what they did is in conjunction with the British government and the Commonwealth government Australia, well the Commonwealth government of Australian government, even Tasmania, they all decided that what they'd do they'd deport their children. And in hindsight the hardest thing about that was that I was under the assumption, or under the impression, that my parents were killed during the Blitz. And when I came out here to Tasmania um that was a sort of security blanket when people asked 'where's your parents' and I naturally assumed they'd been killed during the war.

Caroline Evans: Uh Michael are you still in touch with some of the boys you came to Australia with?

Michael Harvey: Yes we're in touch, we have been in touch for as many years as what we've been out here, which is uh sixty odd years. And we've all grown up together, we've had families, we're uncles or we're aunts, or they`re aunts, uh we've all adopted each other. If I, my children to my friends they're family, I'm uncle or Kay is Auntie Kay. And it's evolved over the years because of circumstances. We had no one to turn to, and we stuck together. As I said, I was at a funeral the other day for, going back about six weeks ago, one of the boys who came out from England with me. He was at a different orphanage but went to the same school, and he died and unfortunately, he died of a massive heart attack, but he was suffering badly from senile dementia. He went before his time, he was only sixty-five. And, but over the years we've all mixed together, or grown up together, barbeques, met each other's families, gone out together and played golf together, and basically, we call in on each other and uh keep in touch…

Barat Ali Batoor: When the story was published in the Washington Post and after that that things…

Fay Anderson: They were syndicated.

Barat Ali Batoor: Went wrong and it started in discussion in the government or in Afghanistan that things got really worse and sensitive, and I started receiving threats.

Fay Anderson: Death threats?

Barat Ali Batoor: Death threats, yeah, people came to my house and uh I was not, as of that time, few times they came and then I had to quickly leave Afghanistan and went back to Pakistan.

Fay Anderson: So, do you think the warlords started to…

Barat Ali Batoor: Yeah. The warlords, yeah, they are now mostly in power in the government, so they're…

Fay Anderson: So, you left Afghanistan…

Barat Ali Batoor: Yeah

Fay Anderson: Was that in 2009?

Barat Ali Batoor: 12

Fay Anderson: 12

Barat Ali Batoor: 12, right after the uh publication of the story.

Fay Anderson: Right

Barat Ali Batoor: Then I left to Pakistan. Um yeah, I was in Pakistan for a little while and then I came to Australia.

Barat Ali Batoor: …then I found a smuggler and I said 'I have cameras with me and I want to document my journey, I will only go with you if you allow my camera with me' because uh the smugglers there in Indonesia are very strict and suspicious. They, before taking you on the boat they strip search you and take all your mobile phones and everything.

Fay Anderson: Right.

Barat Ali Batoor: And they do it because they are afraid that their trips will be tipped off to the police and they will be arrested or something so people spy on that. So they don't let anything, so I, I agreed with him 'if you let me, I will only go with you if you allow my camera'. They said 'ok I will allow you, but don't take any photos before we are all on the boat', and I said 'ok, I will not take photos before I am on the boat'. But, an then we agreed and I went on the boat and we started with our journey. The next day I started to take photos on the boat and uh and the first night went ok, the second, the day was ok, the following night the water got rough and uh our boat leaked and one of the engines stopped, so it was really dis- it was really bad situation, the water was really rough and like how the boat was floating…

Fay Anderson: How many people were with you?

Barat Ali Batoor: 93 on boat.

Fay Anderson: 93!

Barat Ali Batoor: 93 on a small fishing boat. And with the Indonesian crews, like 96 in total. Uh so yeah, we all really lost hope that this is it. And uh, I remember there are rumors that they`d recently died at sea…

Fay Anderson: Is that when you discovered this? No, you already knew…

Barat Ali Batoor: No no, I already knew. So, recently died, they were probably in the same situation like us.

Elba Cruz-Zavalla and her family fled from Chile to Argentina, after the coup d'etat against President Salvador Allende in 1973. In this segment she talks about finding other Latino migrants shortly after arriving in Adelaide as a refugee in 1977.

Greg Power, Portrait of Elba Cruz-Zavalla during her visit to the National Library of Australia, 20 July 2005, nla.obj-131583131

Everest Pitt talks about her arrival in Far North Queensland at the age of 21 in 1974 from Fiji. In her interview she talks about her life in Fiji and her experiences of settling in to Australia.

Leigh Henningham, Portrait of Everest Pitt, Fijian-Australian Collecting Project in Cairns, Northern Queensland, 2022, 1, nla.obj-3110047380

Leigh Henningham, Portrait of Everest Pitt, Fijian-Australian Collecting Project in Cairns, Northern Queensland, 2022, 2, nla.obj-3110047460

Margaret Yung Kelly talks about her first impressions of Sydney after migrating from Shanghai in 1950. Her father was born in Lismore, New South Wales so he was a British subject who was able to bring members of his family to Australia.

Anna Zhu, Margaret Yung Kelly, Sydney, New South Wales, 25 March 2022, 1, nla.obj-3050300746

Anna Zhu, Margaret Yung Kelly, Sydney, New South Wales, 25 March 2022, 2, nla.obj-3050300826

Michael Harvey, born in Westminster, England talks about his experiences as a child migrant to Tasmania after World War II. He was eventually able to find his mother in 1995 through the Child Migrant Trust and travelled to England with his twin brother to meet her.

Caroline Evans, Portrait of Michael Harvey for the Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrants oral history project, 2012, nla.obj-228953399

Barat Ali Batoor, who belongs to the Hazara ethnic group talks about his journey fleeing Afghanistan through Pakistan, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia to Australia in 2012. He was granted refugee status in 2013 and continues his work as a freelance photographer.

Barat Ali Batoor, Towards the main vessel, 2012-2013, nla.obj-2963497309

Barat Ali Batoor, Island of hope, 2012-2013, nla.obj-2963497720

Barat Ali Batoor, Scrambling off the boat, 2012-2013, nla.obj-2963497748

Experience the Library's 2024 Enlighten illuminations for more stories of migration, multiculturalism, sadness, joy and courage told through our oral histories and pictures.

Visit us

Find our opening times, get directions, join a tour, or dine and shop with us.