Information sources

We constantly make decisions about the information we consume. Sometimes we take it in, sometimes we dismiss it. It may or may not interest us. It might be relevant to a task we’re working on, or we might just dislike the way it’s presented. These judgments—conscious or not—are an important part of how we engage with information.

Media, information and digital literacy skills help us understand these choices and give us the tools to evaluate and manage the sources of information around us.

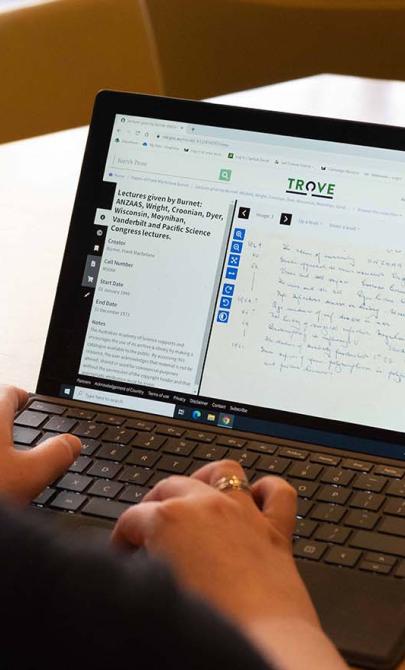

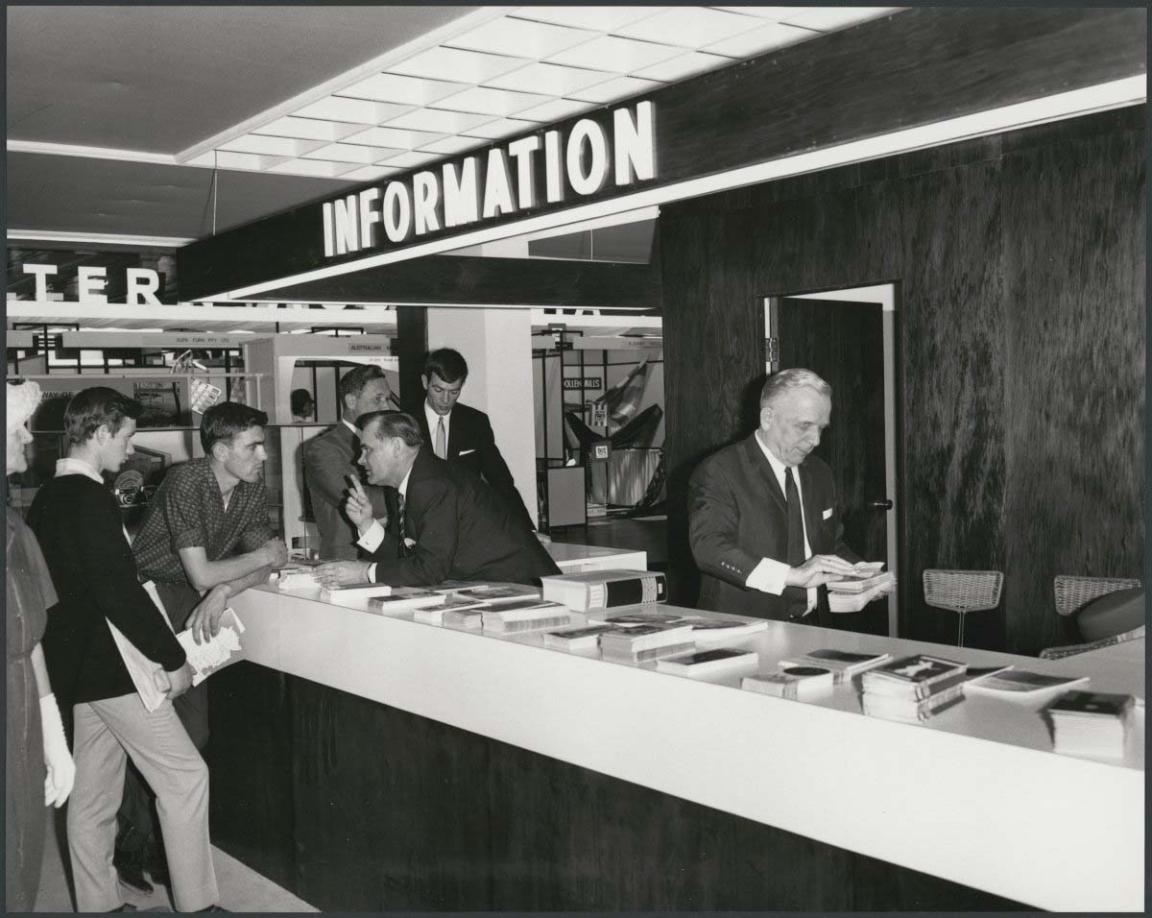

Wolfgang Sievers, Information desk at German stand, Exhibition Building, Melbourne, Victoria 1966, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-161478886

Wolfgang Sievers, Information desk at German stand, Exhibition Building, Melbourne, Victoria 1966, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-161478886

Understanding sources

A source is the origin of information. It can be anything—from books and television programs to people or social media posts.

Sources are commonly grouped into 3 types, depending on how closely they are linked to the original information.

| Primary | Secondary | Tertiary |

|---|---|---|

First-hand, original material Examples:

| Interpretation or analysis of primary sources Examples:

| Collections or indexes of information

|

After identifying the type of source, it’s important to assess how trustworthy and reliable it is.

Where to start when critically engaging with media and identifying sources with students (with Michelle Ciulla Lipkin)

Media Literacy Basics Bias & Agenda - Media Literacy And Student Engagement

Finding sources and information

Physical sources

Libraries are a good starting point for finding printed material such as books, magazines and newspapers. They are usually free to access and staffed by people who can help guide your search.

The National Library of Australia collects items that tell the Australian story—materials created by Australians, in Australia, or about Australia and its people.

Under the Copyright Act 1968, the Library is responsible for collecting all material published in Australia through legal deposit. This means it holds a wide range of views and perspectives, not selected based on value judgments.

This diversity allows researchers to explore many viewpoints and use primary sources to help assess the reliability of information. An example of this approach can be seen in Interpreting the Collection – Art: The Death of Cook.

Digital sources

Loui Seselja & E. A. Crome, Internet terminals, International Terminal, Cairns Airport, Cairns, Queensland, 18 June 2005, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-131314479

Loui Seselja & E. A. Crome, Internet terminals, International Terminal, Cairns Airport, Cairns, Queensland, 18 June 2005, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-131314479

Using a search engine can return thousands of results. When researching online, it's important to think critically about each site. Domain suffixes can help indicate the source's reliability.

Some common Australian domain suffixes include:

- .au – An Australian website hosted on the Australian Web Domain

- .gov.au – An Australian Government Agency

- .org.au - a registered Australian organisation

- .edu.au – an accredited Australian educational institution or associated organisation

- australia.gov.au – Official website of the Australian Government

- library.gov.au – website of the National Library of Australia

- acara.edu.au – the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA)

- redcross.org.au – official site of the Red Cross organisation in Australia

Once a website has been entered, the information within can be appraised with the criteria in the following section “What is a trusted or credible source”.

The domain suffixes above are examples of Australian sites. Examples from other countries include:

- natlib.govt.nz – National Library of New Zealand

- nationallibrary.gov.in – National Library of India

- bl.uk – British Library

- loc.gov – Library of Congress (USA)

Note: Many US websites do not include a geographic suffix.

Indentify a trusted or credible source

A trusted source is one known to consistently provide reliable and accurate information, regardless of whether it’s primary, secondary or tertiary.

When evaluating a source, consider the following:

Authority:

- Who created the work?

- What are their qualifications?

- Is the work peer reviewed?

- Does the author have cultural authority on the topic?

Currency:

- When was the source published?

- Is it the most up-to-date version?

- Are cited sources current?

Accuracy:

- How accurate does this information seem?

- Are there any indications of hyperbole, exaggeration, generalisations, or impossibilities?

- Does the author cite the source of their information?

- Is there any exaggeration or misleading language?

NOTE: Even high-quality sources can become outdated over time and are superseded by new information and findings.

Bias:

- Is the information objective?

- Is the language neutral or persuasive?

- Does the source show all sides of an argument?

- Does the work make critical judgements about a person or idea without facts?

- What do I know about the author/creator and their authority on this subject?

- What do I know about the publisher of this work? Do they have a history of only presenting certain types of information?

Purpose:

- Why was this work created? What was the motivation? (can be multiple)

- Entertainment?

- Information sharing?

- Persuasion?

- Political gain?

- “Likes”/“hits”/clicks?

- Something else?

- How is the information presented? What kind of format(s) does it exist in?

- Who initiated this work? Was it the creator’s idea or was it commissioned/ordered by someone else?

- Who is the target audience of this work?

- What kind of language is being used (academic, plain language, industry specific)?

- Who benefits from people engaging with this work?

Not every source will clearly answer all these questions. Use your judgement to decide how trustworthy and relevant it is for your needs. For example: A 1950 census is a reliable historical record, but not useful for current demographic information.

Learning activities

Activity 1: Categorise sources

Give students a range of sources and a guiding research question. Ask them to categorise each source as primary, secondary or tertiary.

Activity 2: Reassess sources with a new topic

Change the topic and have students reassess the same sources using the five criteria for evaluating sources. Discuss how a source’s classification can change depending on the context.

Activity 3: Discuss source reliability

Talk about how the reliability of a source can shift based on the situation or question being asked. Ask students to reflect on sources they’ve encountered today or this week—such as websites, news articles or social media—and explain how they judged whether those sources were reliable.