Religious and social significance

A view from Tahiti and the Society Islands

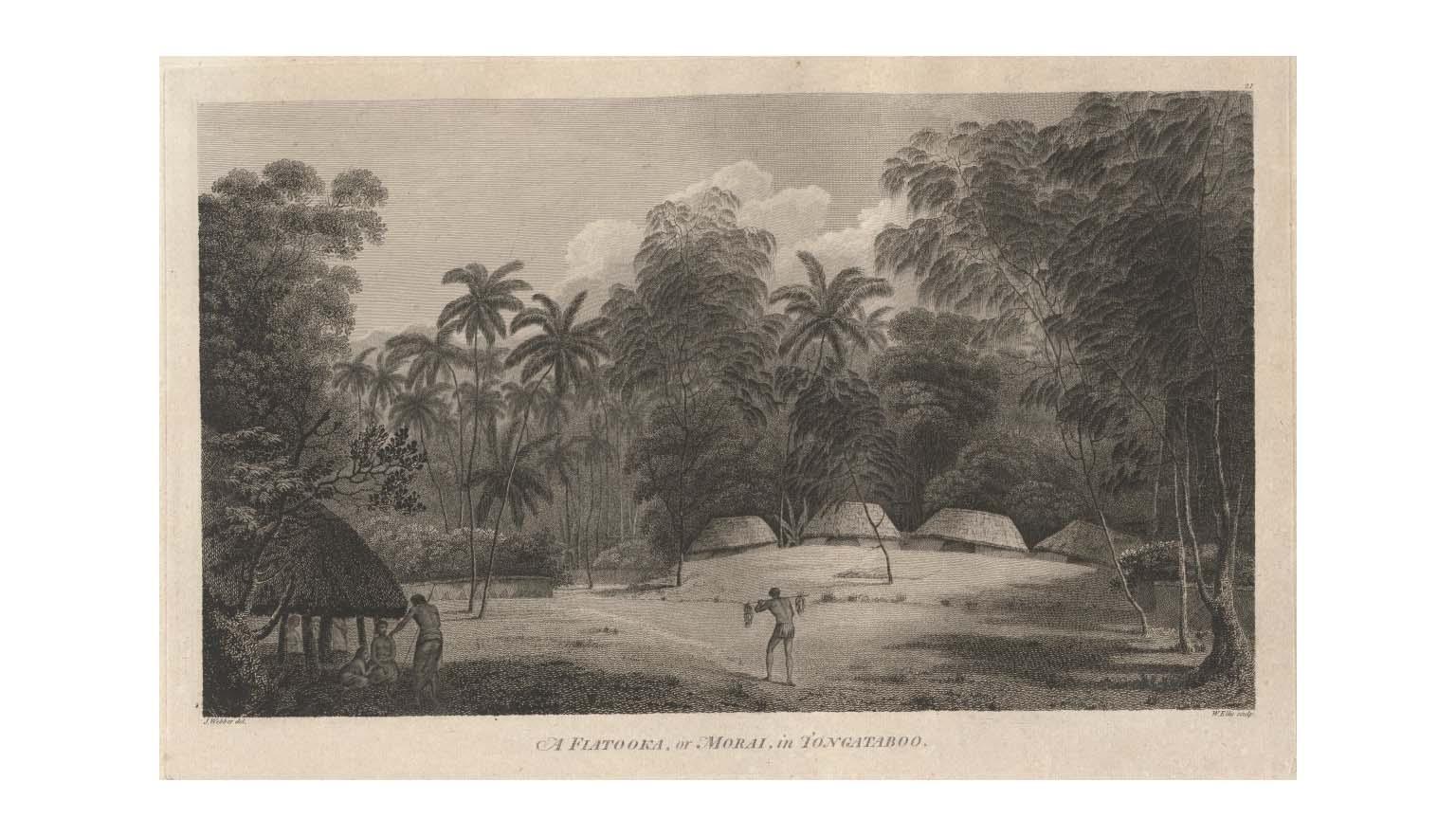

Open-air temples built of stone and coral were known as marae in the Cook Islands, Tahiti, the Tuamotu Islands and Aotearoa, me’ae in the Marquesas Islands, heiau in Hawaii, and ahu moai on Rapa Nui. Tongan mala’e and Samoan malae also refer to ceremonial plazas.

Despite linguistic and architectural variations across the region, all of these sites pertain to the pan-Polynesian marae concept: a sacred (tapu) place of interactions between the ao, the world of the living, and the pō, the world of deities and ancestors.

Nowadays, thousands of marae ruins are scattered in the island valleys and attest to their prominence in ancient chiefdoms.

The elements of a Tahitian marae

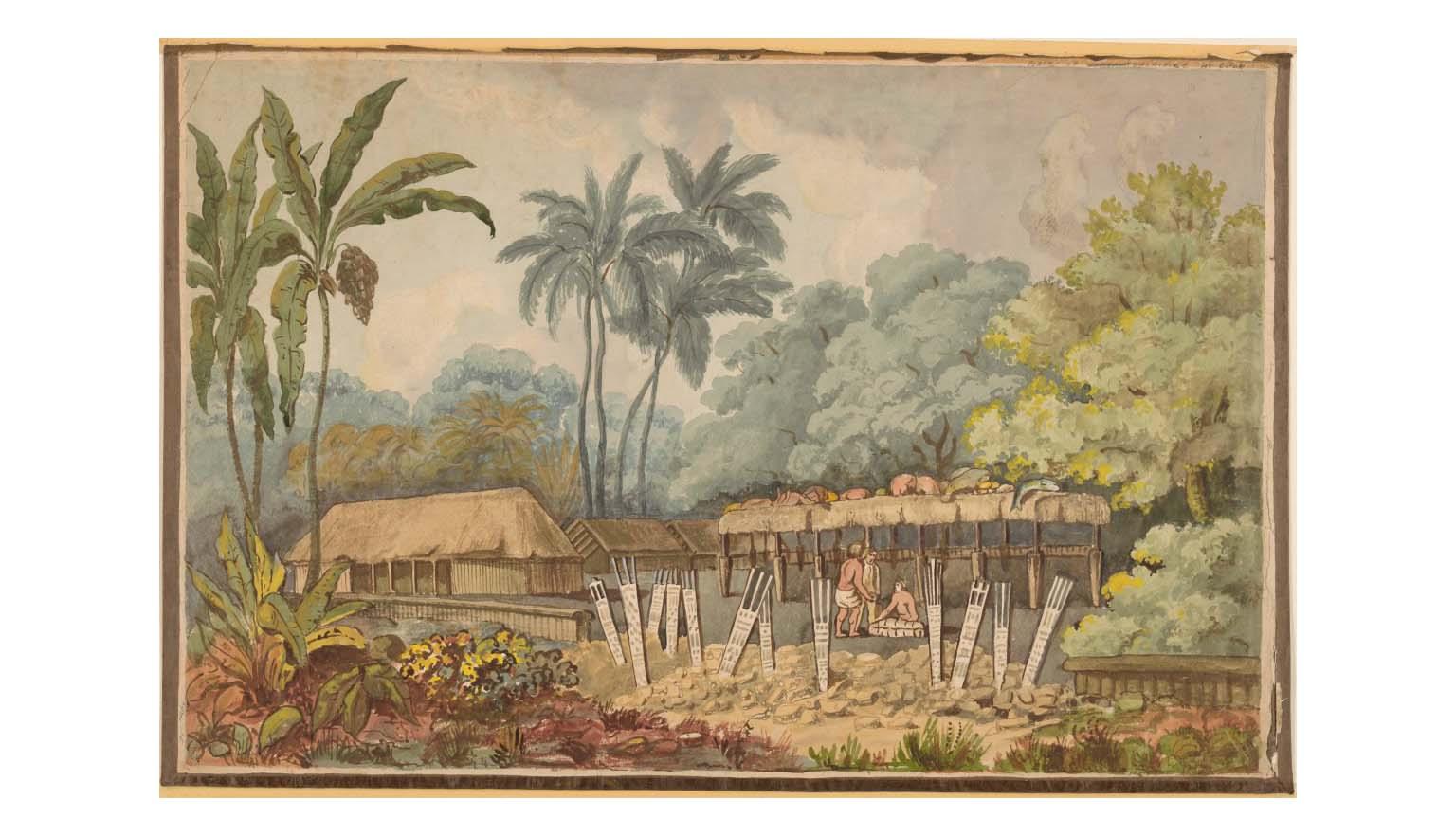

In the Society Islands, including Tahiti, marae were ceremonial spaces built around a central courtyard, often enclosed by low walls. At one end stood the ahu—a platform made from stone or coral, like an altar. The largest marae in Tahiti, Maha‘iatea, had a stepped ahu that reached 80 metres in length and 10 tiers high.

People placed upright stones—sometimes carved to resemble human figures—on the ahu. These stones represented the spirits of gods or ancestors, and priests decorated them with flower garlands and offered them food. Other stone seats in the courtyard showed each person’s rank and position during ceremonies.

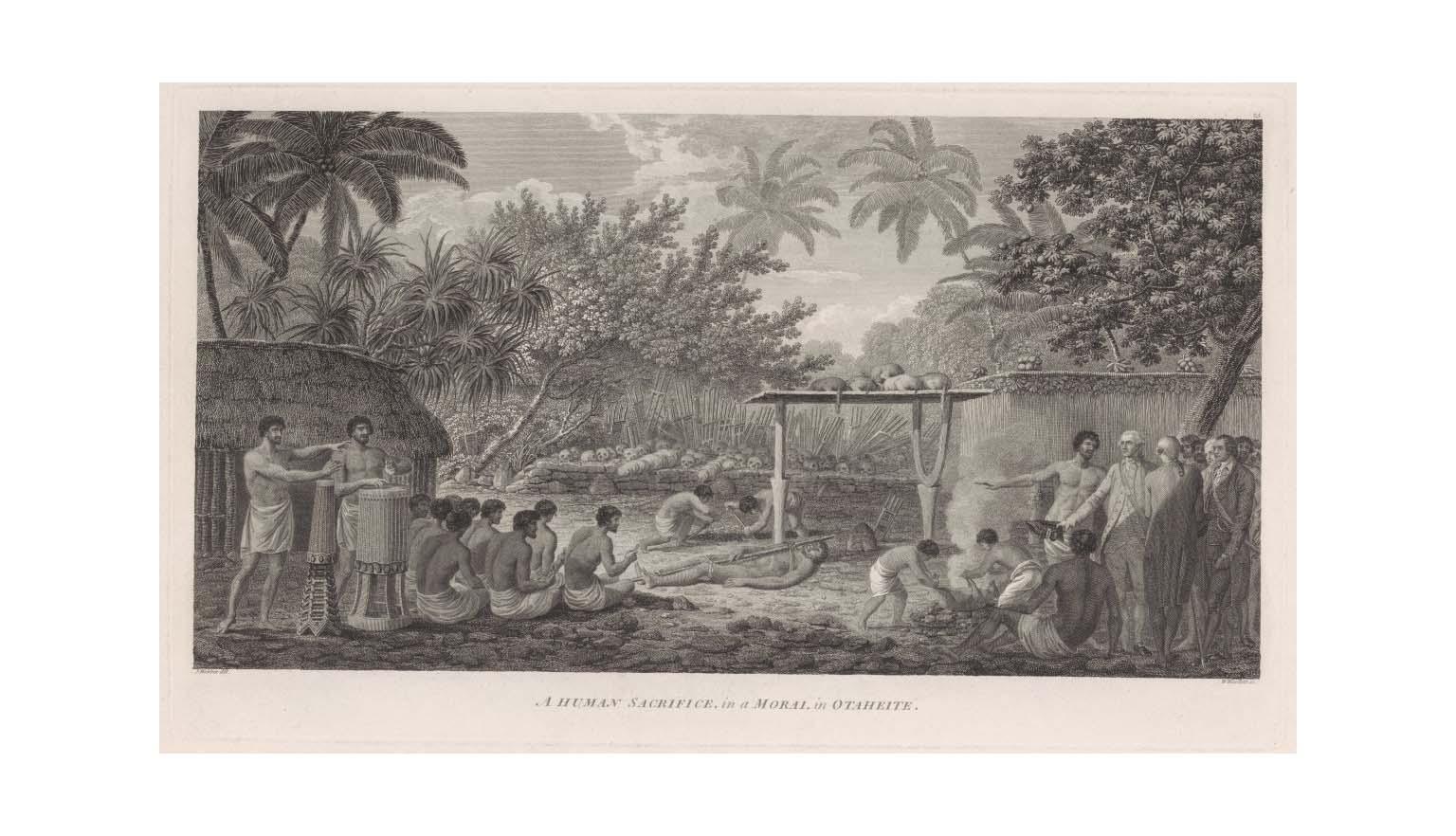

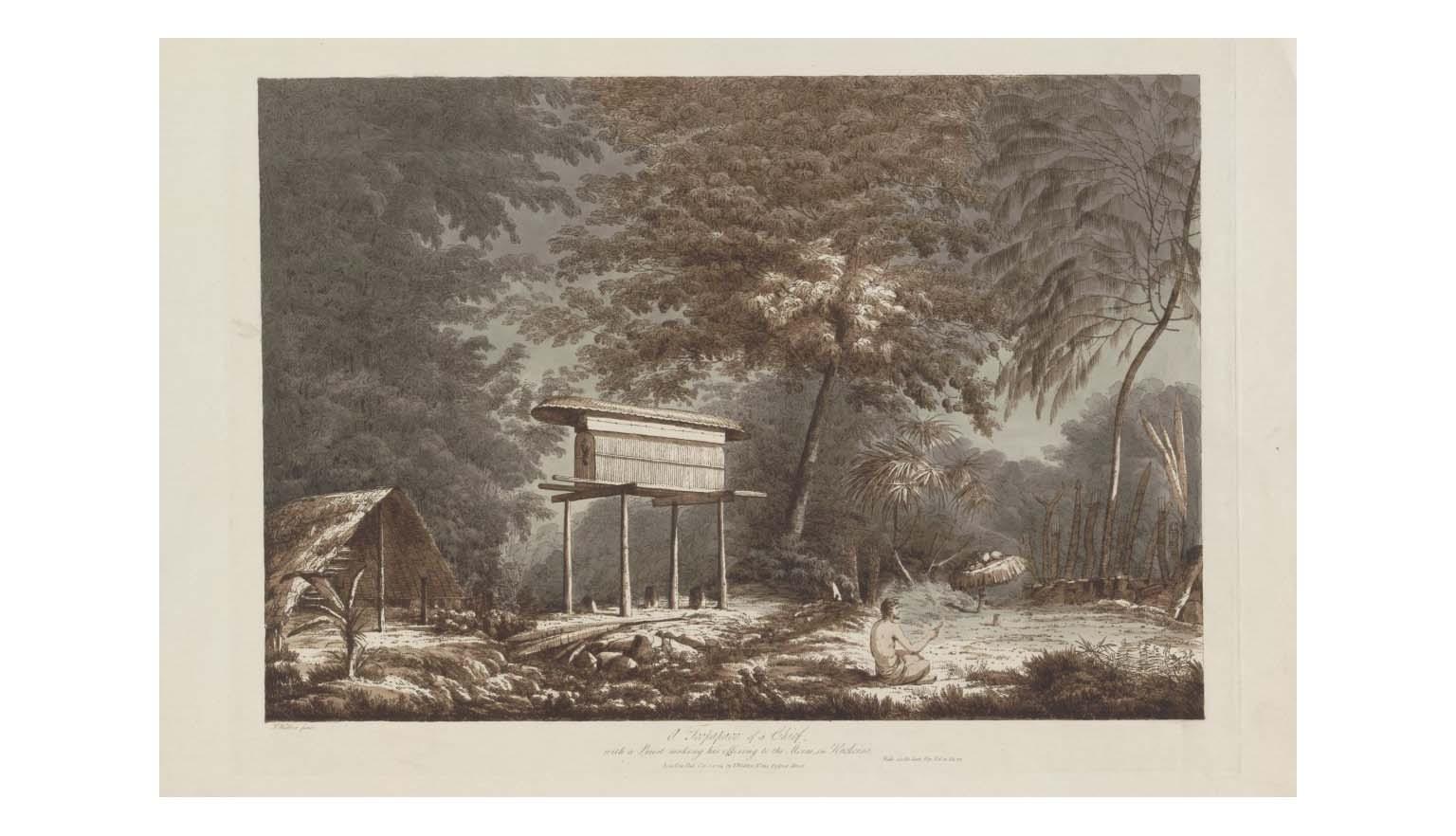

Although only the stone elements remain today, people also built other parts of the marae using wood, fibre and leaves. They stored sacred items such as plates, drums and carved to‘o figures in a building called the fare ia manaha. They placed offerings of bananas, pigs and fish on raised wooden platforms with conical posts designed to stop rats from reaching the sacred food. Carved boards called unu featured animal designs that showed group identity.

The rituals conducted at the marae

Before European contact, people held many rituals at the marae. Catholic and Protestant missionaries later banned these so-called ‘pagan’ practices, and many communities abandoned or destroyed their marae.

Oral traditions still describe how different groups—families, skilled workers and high-ranking chiefs—used ceremonies for spiritual and social purposes.

Some rituals focused on fertility and abundance. People prayed for good harvests or successful fishing trips. The rise of the Pleiades constellation, known as matari‘i i ni‘a, signalled the start of the abundance season. People celebrated this event at the chief’s marae. In the Tuamotu Islands, communities treated the season’s first turtles as ancestral gifts. They sacrificed, cooked and shared these turtles during ceremonies.

Other rituals prepared warriors (to‘a) for battle or celebrated peace after conflict. Skilled workers (tau‘a), such as canoe builders, performed trade-based rituals. Before building a new canoe, they brought their adzes to the marae and ritually ‘put them to sleep’, giving the tools mana—spiritual power.

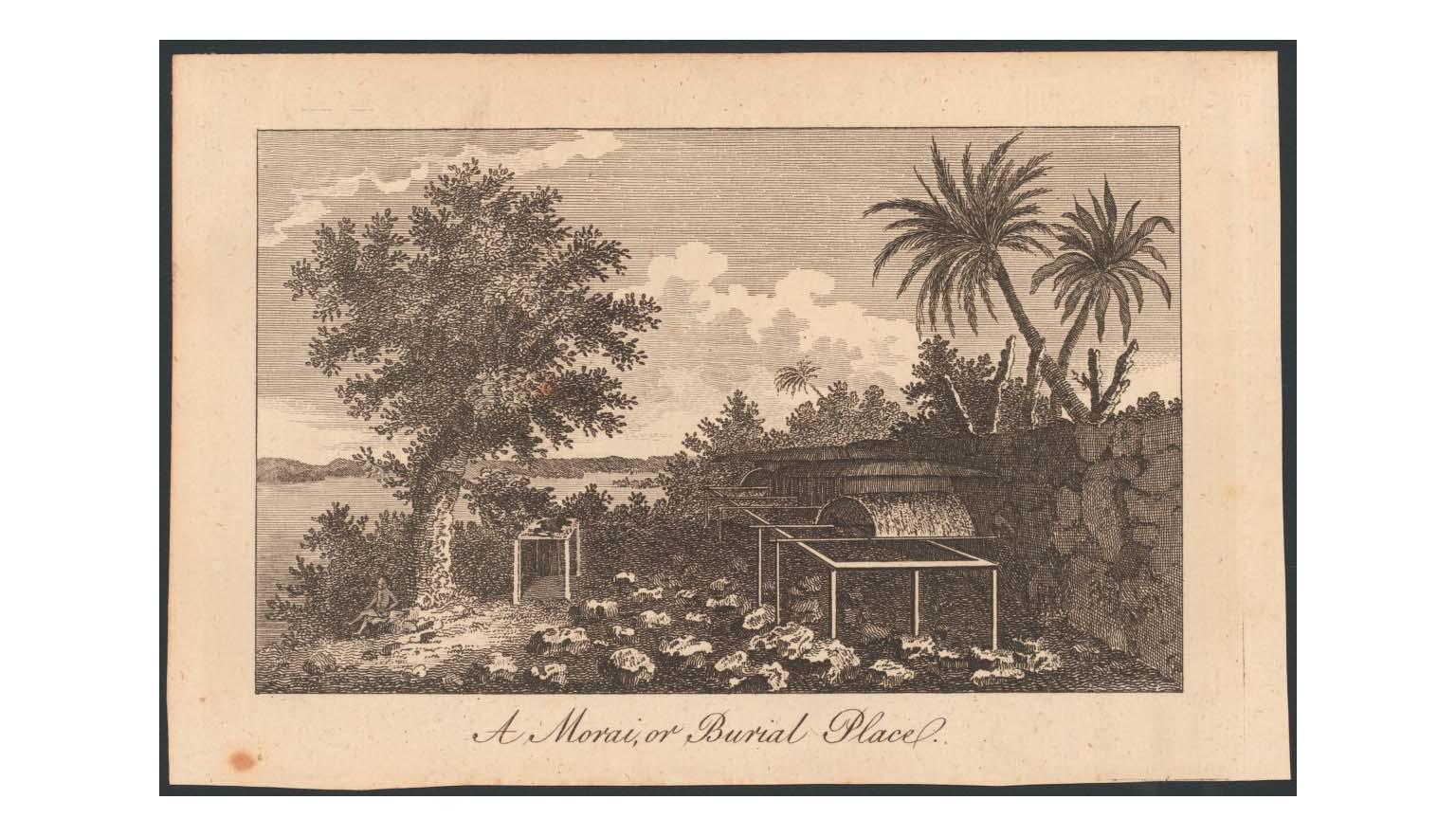

Marae also served as ancestral shrines. European drawings show funerary platforms (fara tupapa‘u) where people laid the bodies of important chiefs for weeks or months. During mourning, priests wore barkcloth (tapa) costumes decorated with pearl shell. Later, they collected the bones and hid them in niches or mountain caves.

Families continued to visit their marae to offer food and recite genealogies in honour of their ancestors. They remembered these deified ancestors in stone carvings, such as the tiki of the Marquesas Islands and the moai statues of Rapa Nui.

The marae as places of socio-political power

Powerful chiefs (ari‘i nui) built the largest and most elaborate marae, using their scale and complexity to assert authority and influence.

On Raiatea, the Tamatoa dynasty ruled from the Taputapuātea marae complex. Chiefs and navigators from across Polynesia gathered at the main marae, which they dedicated to the war god ’Oro. One section, Hauviri, hosted inauguration ceremonies for new chiefs.

During these events, the chief sat with his back to a large white stone while priests presented him with the maro ‘ura—a sacred red-and-yellow feathered belt. They also revealed the god ’Oro’s sacred figure, usually kept hidden. These figures (to‘o) were wooden forms wrapped in plaited rope (sennit) and decorated with feathers.

UNESCO recently recognised the cultural importance of Taputapuātea on the World Heritage List.

Marae were thus more than just ceremonial sites. Their hierarchy mirrored the social organisation of the chiefdom, from the small family shrines to the large temples that cemented political alliances. Marae further represented the connection of a group to their ancestral lands, the history of their clan: in other words, their identity.

The restoration of many marae sites, conducted by archaeologists and cultural bodies, contributed to the Polynesian renaissance in the 1970s. Marae embody Polynesian origins, histories and traditional connections, and they are progressively reinvested as places of sharing and celebrations of the Polynesian identity and living culture.

Learning activities

Activity 1: Symbols of Power and Belief

Various materials in Polynesian societies held symbolic connections to gods and ancestors. Treasured items such as boar tusks symbolised strength and were worn by warriors, while woven human hair from ancestors reinforced family ties. The pursuit of these symbolic treasures sometimes involved dangerous journeys or conflict between rival villages.

Research a traditional ceremony from a Polynesian society.

- What is the purpose of the ceremony?

- What special materials are worn or used?

- Are there ceremonial objects or spaces?

- What symbols are present, and what do they represent?

Encourage students to present their findings through a short report, a presentation, or a creative visual representation such as a poster or digital collage.

Activity 2: Stories in the Skin

In many Polynesian and Pacific societies, body marking is a deeply meaningful tradition. Using bone chisels and natural pigments, artisans created intricate tattoos representing identity, status, and cultural stories. In Samoa, tattoos marked the transition from adolescence to adulthood, while in Māori culture, women's facial tattoos (such as the moko kauae) symbolised lineage and social standing.

Investigate the traditional tattooing practices of a Polynesian or Pacific Island culture.

- What do the symbols and patterns mean?

- Who is allowed to receive certain tattoos?

- Are some designs reserved for specific genders or social roles?

- Are there rituals or conditions that must be met before receiving a tattoo?

- Are similar symbolic tattoos found in other cultures around the world?

Students can compile their research into a visual chart or create a fictional profile of a person from that culture, explaining the meanings behind their tattoos.

Activity 3: Marked for Life

Have students reflect on the concept of permanent symbols, such as tattoos, in expressing cultural identity.

- Why might someone choose to carry a symbol on their body for life?

- How do these symbols connect people to their ancestors or cultural history?

- What are the similarities and differences between traditional Polynesian tattoos and modern body art?

Students could write a short reflection or participate in a classroom discussion about how culture and identity are expressed through physical symbols.

About Guillaume Molle

Guillaume Molle is a Senior Lecturer in Pacific Archaeology, an Australian Research Council DECRA Fellow at the Australian National University, and Deputy Director of the International Centre for Polynesian Archaeological Research (CIRAP) in Tahiti. His doctoral research at the University of French Polynesia (2007–2011) focused on the pre-contact history of Ua Huka in the Marquesas Islands. He is particularly interested in human settlement across the Pacific and is developing an archaeological approach to ritual to better document ancient Polynesian religious systems. He has led or co-led numerous research missions in the Marquesas, the Gambier and Tuamotu Archipelagos, and on the atoll of Teti’aroa. He has published extensively in scholarly journals and monographs and is currently preparing a volume on the archaeological history of the Marquesas Islands, to be published by the University of Hawai‘i Press.

Learn more about Guillaume Molle and his research