Exploring the universe: Australia’s history with astronomy

Every August, Australia celebrates National Science Week. The 2025 National Science Week falls on 9 to 17 August and the theme for this year is ‘Decoding the Universe – Exploring the unknown with nature’s hidden language.’

Philip Gostelow, Amateur astronomers gazing through telescopes into the night sky during the Murchison Astrofest, Western Australia, 17 August 2013, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-153314469

Philip Gostelow, Amateur astronomers gazing through telescopes into the night sky during the Murchison Astrofest, Western Australia, 17 August 2013, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-153314469

Australia’s history of ‘decoding the universe’ is a tale of international collaboration and innovation. This National Science Week, take a look back through some of the people and places which have shaped our understanding of the universe.

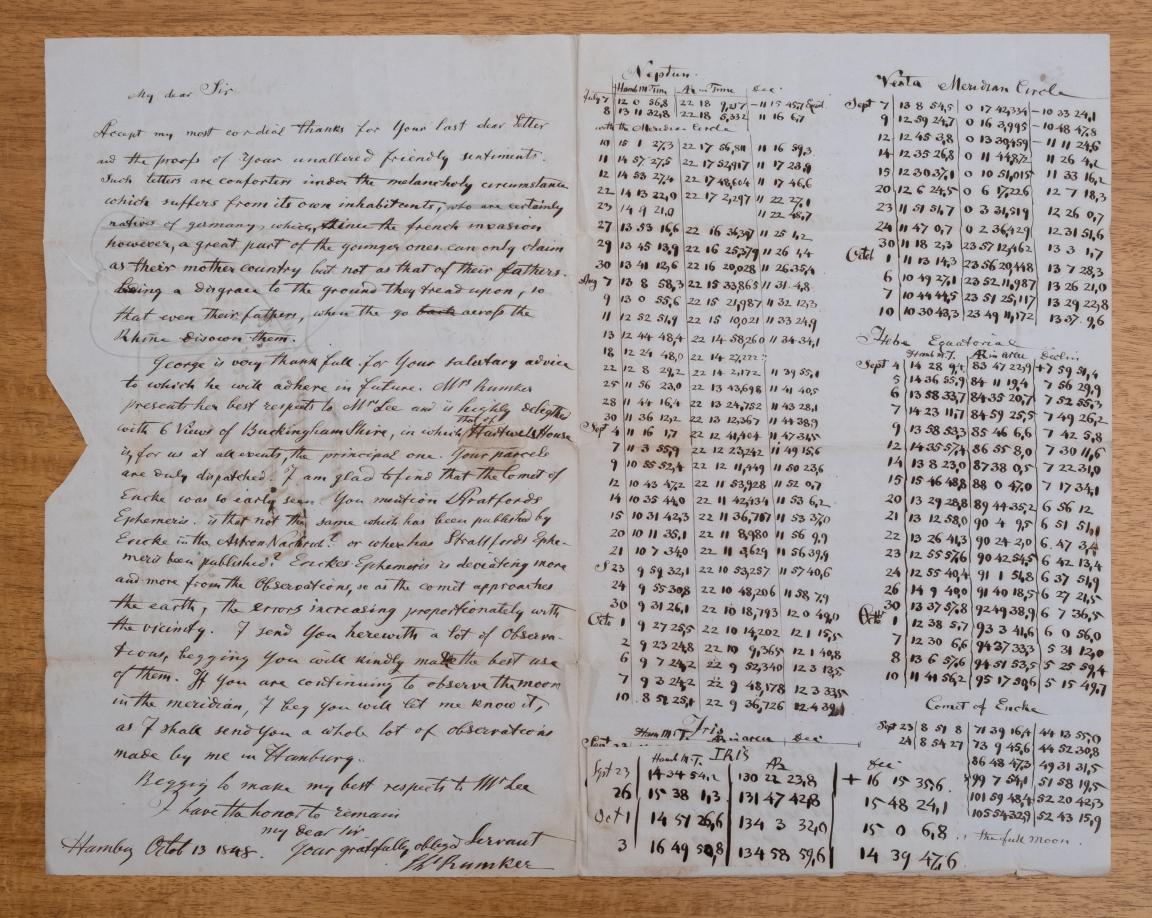

Corresponding about the stars

We recently acquired a collection of letters by Charles Ludwig Christian Rümker (1788-1862), Australia’s first Government Astronomer from 1827 to 1830. Rümker worked at the Parramatta Observatory in Sydney. These letters, written after Rümker’s return to Europe, provide important insight into how Rümker recorded and communicated his observations with peers.

Letters by Australia's first government astronomer, Carl Ludwig Christian Rümker

My name is Lilia and I’m a collection researcher at the National Library.

I'm here to talk about a brand new acquisition: letters written by Australia’s first government astronomer, Charles Ludwig Christian Rümker.

These letters were written between 1844 and 1864, after he returned to Europe. But they're an incredible example of of early science communication.

Rümker put Australian astronomy on the world stage, when he first observed the return of Encke's Comet in 1822, at the Parramatta Observatory in Sydney.

You can see these letters at the National Library now. They're available in the Special Collections Reading Room and there's also a finding aid online.

Shortly after his arrival in Australia in 1821, Rümker gained international recognition for his rediscovery of Encke’s Comet. Like Halley’s Comet, Encke’s Comet is a periodic comet, which means it orbits the sun and reappears about every 3 years. This comet was the second periodic comet ever recorded (the first being Halley’s Comet).

While it was JH Encke who first calculated its orbit in 1819 and predicted its reappearance, it was Rümker at the Paramatta Observatory who observed its return in June of 1822, catapulting Australian astronomy onto the world stage.

Christian Carl Ludwig Rümker, Letter to John Lee, 13 October 1848, nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn10101751

Christian Carl Ludwig Rümker, Letter to John Lee, 13 October 1848, nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn10101751

Despite his scientific brilliance, Rümker was known to clash with many of his fellow scientists as well as the government officials who employed him. He left the Parramatta Observatory in 1823 after disagreements with peers.

Frank Hurley, Site of Old Observatory Parramatta (Governor Brisbane), between 1910-1962, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-160078413

Frank Hurley, Site of Old Observatory Parramatta (Governor Brisbane), between 1910-1962, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-160078413

He was briefly called back and appointed as the first Government Astronomer in 1827, before further clashes with the British government eventually lead to his dismissal from service. He returned to Europe in 1830.

Rümker’s time in Australia stayed with him for much of his remaining career. He continued to publish on his observations made at the Parramatta Observatory including his Preliminary catalogue of fixed stars. A year before he died, he dispatched his observations at Paramatta to John Lee, president of the Royal Astronomical Society in London.

Words cannot express my gratitude for the kindness which you have in furthering the principal objects to which I have devoted the best time of my life … without your intercedence I should have probably lost all chance of having been able to contribute towards the benefit of science.

Despite Rümker’s difficulties with his peers, the desire to share his knowledge was an intrinsic part of his work. His letters demonstrate the collaboration and communication at the centre of scientific practice. They also highlight the important connections between Australia and the international astronomy community.

The right tools for the job

Everyone thinks it’s satellites, or it’s the moon, or it’s Mars, but really when you’re talking about a space-based capability it’s everything from the capability itself… building the satellites and getting them launched… right through to ground stations… right through to how we process the data and get it to the end users.

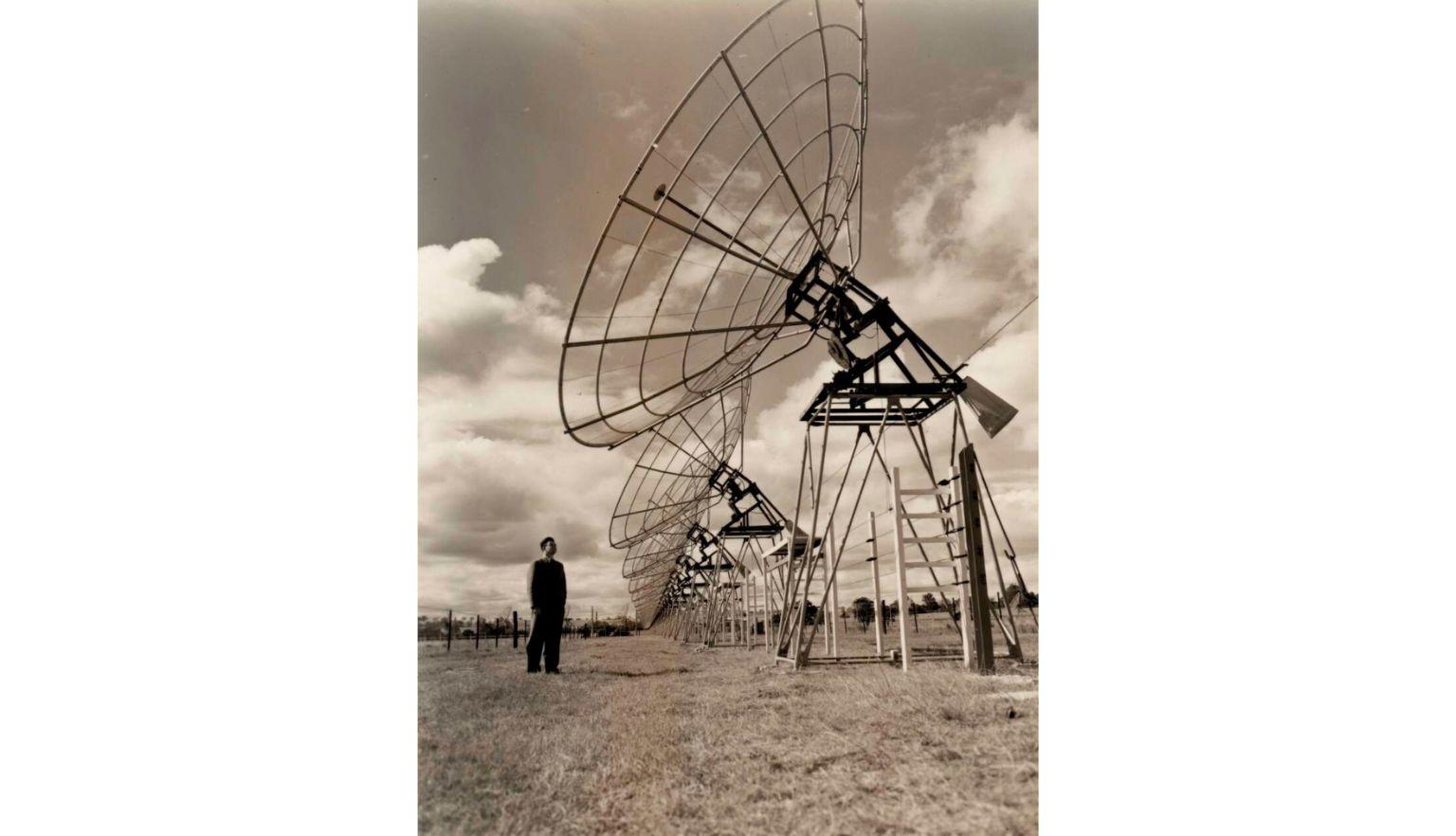

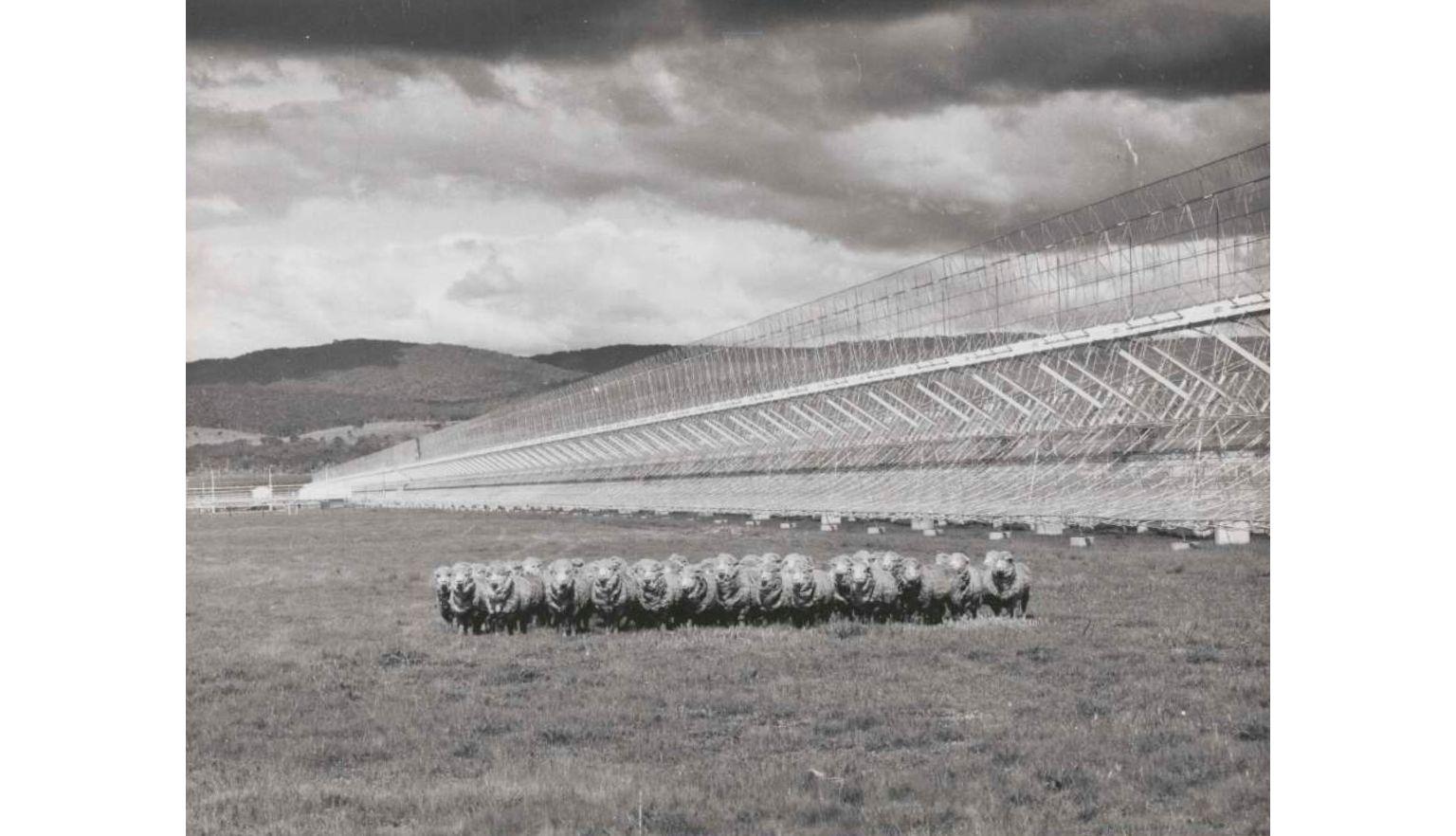

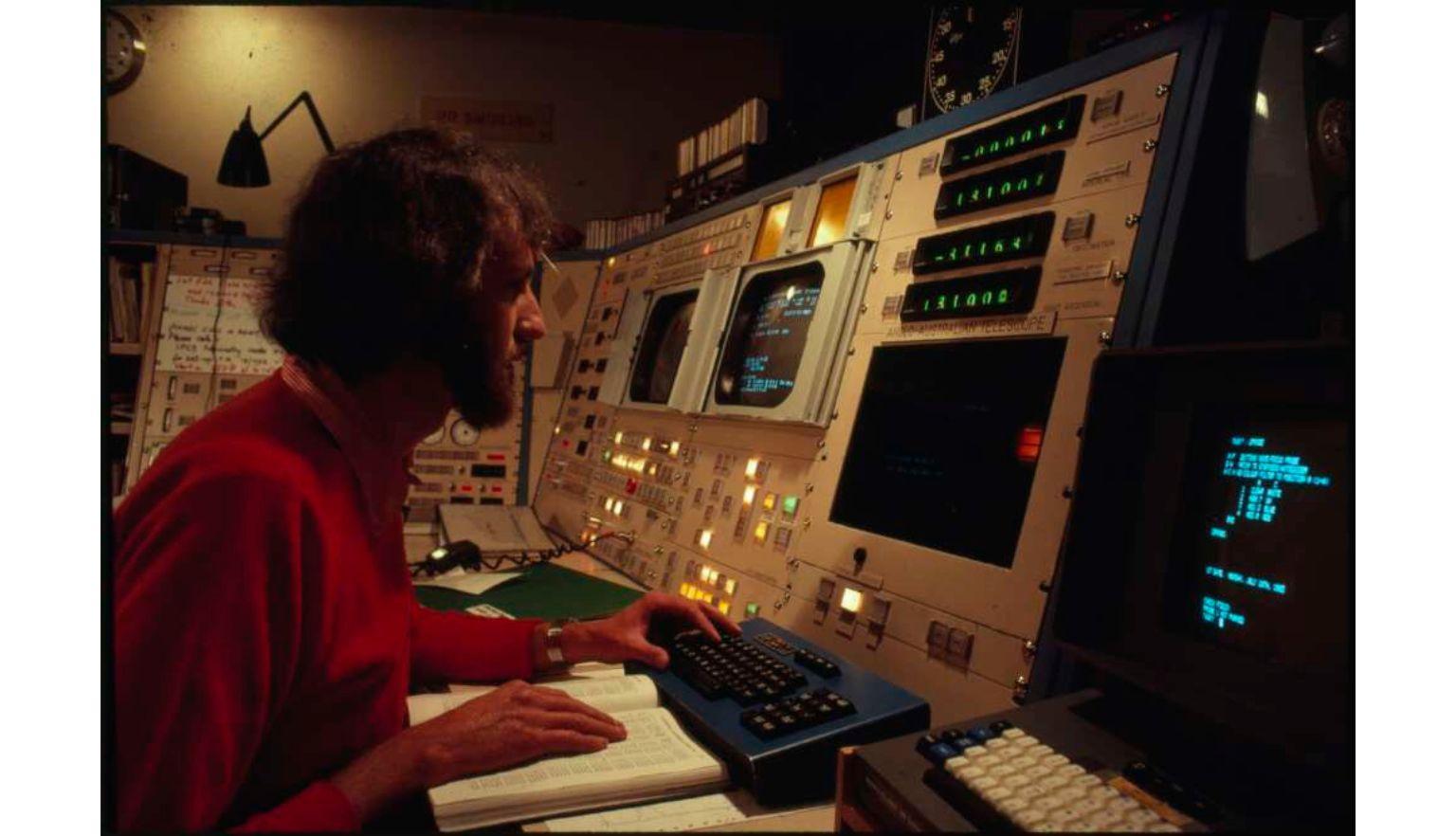

Australia continues to be a world leader in observational and radio astronomy thanks some of the most recognisable scientific instruments in the country: our telescopes.

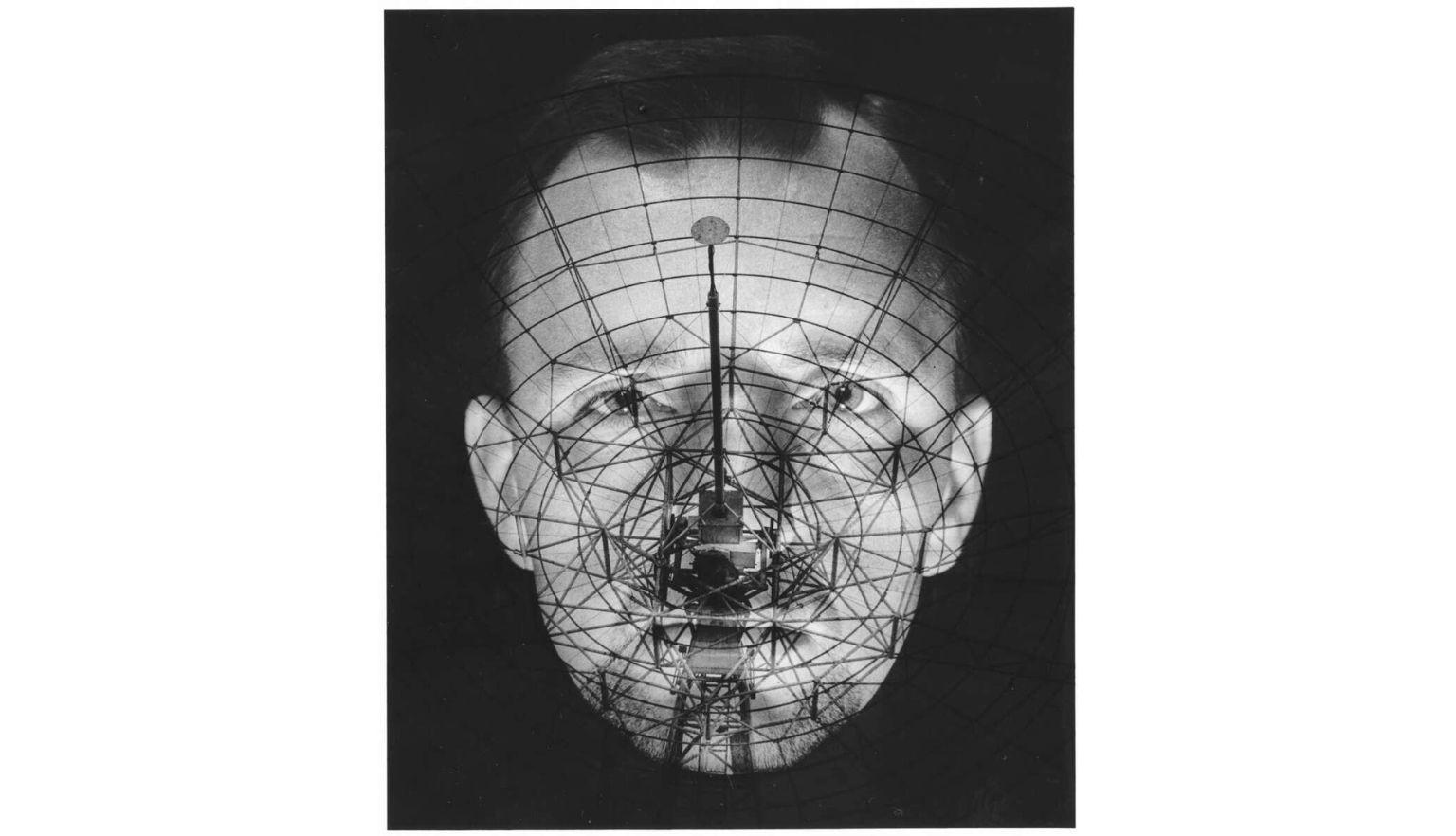

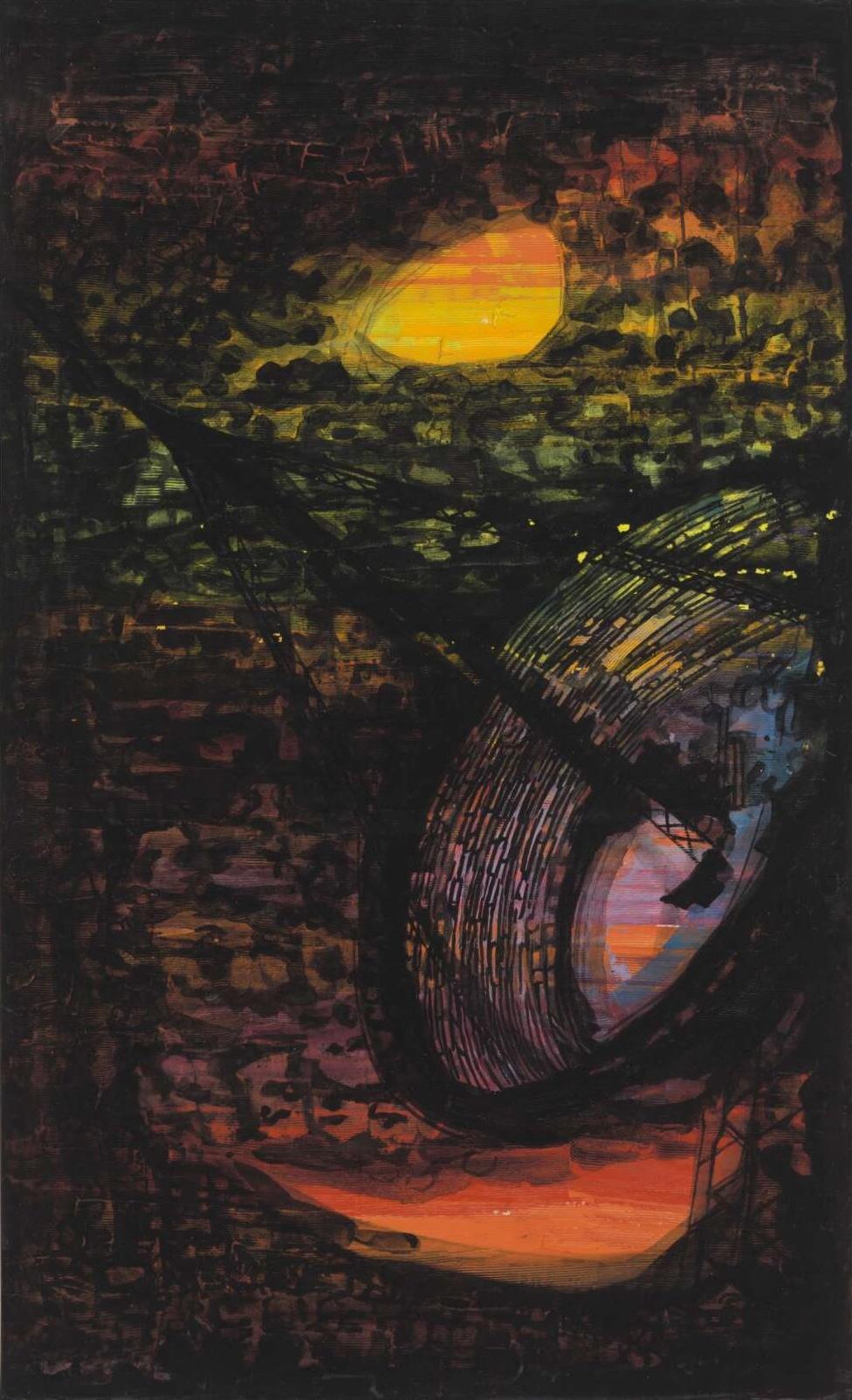

Mathieu Matégot, Study for the Woomera radio telescope tapestry, c.1968, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-138141059

Mathieu Matégot, Study for the Woomera radio telescope tapestry, c.1968, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-138141059

If you’ve visited the Library recently, you might recognise the Woomera radio telescope from the Mathieu Matégot tapestry in the foyer. This telescope in South Australia was the first NASA deep-space station outside of the United States. It is symbolic of the technological era in which the Library was built and participation in the international astronomy community. Learn more about our building art.

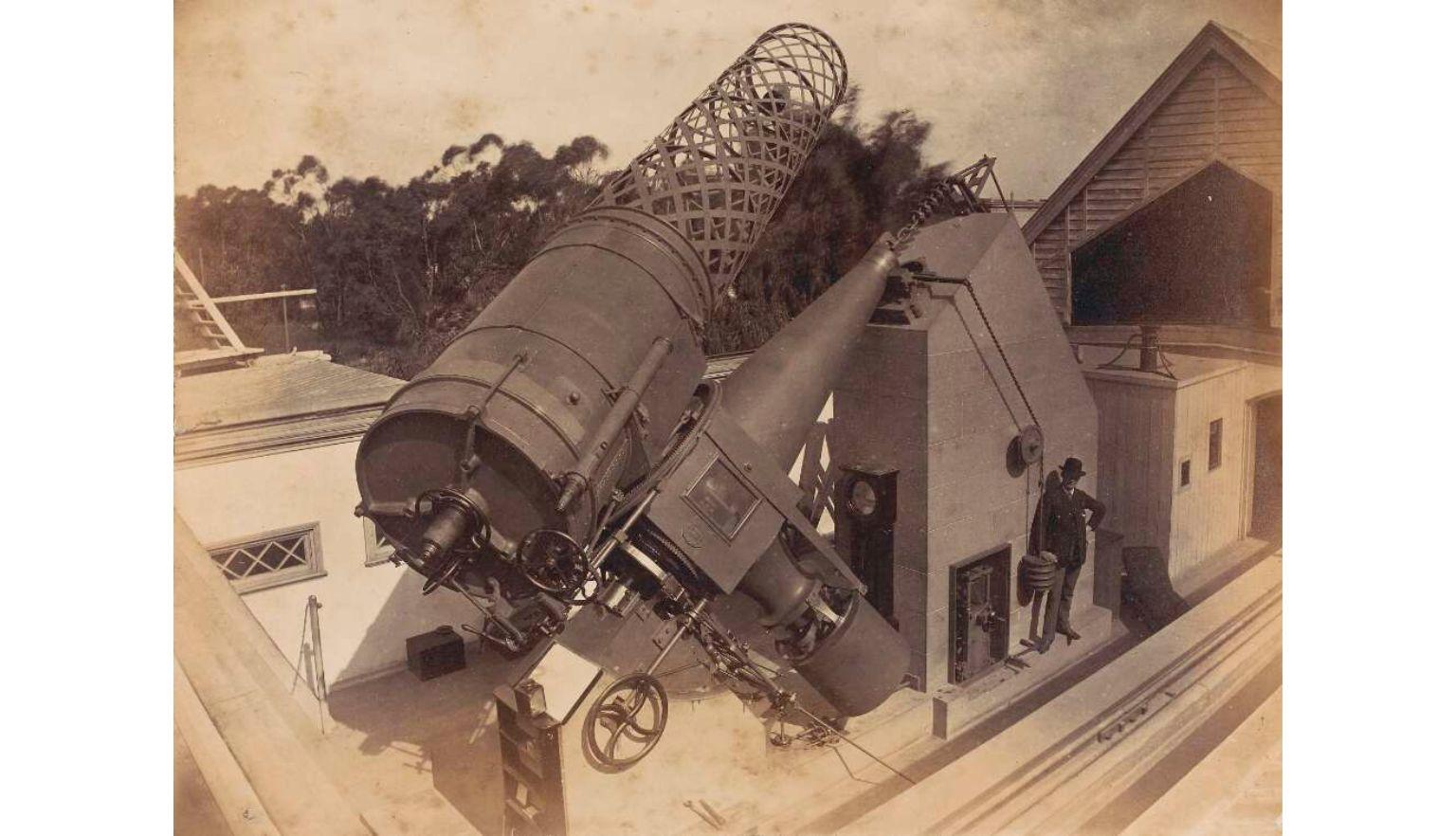

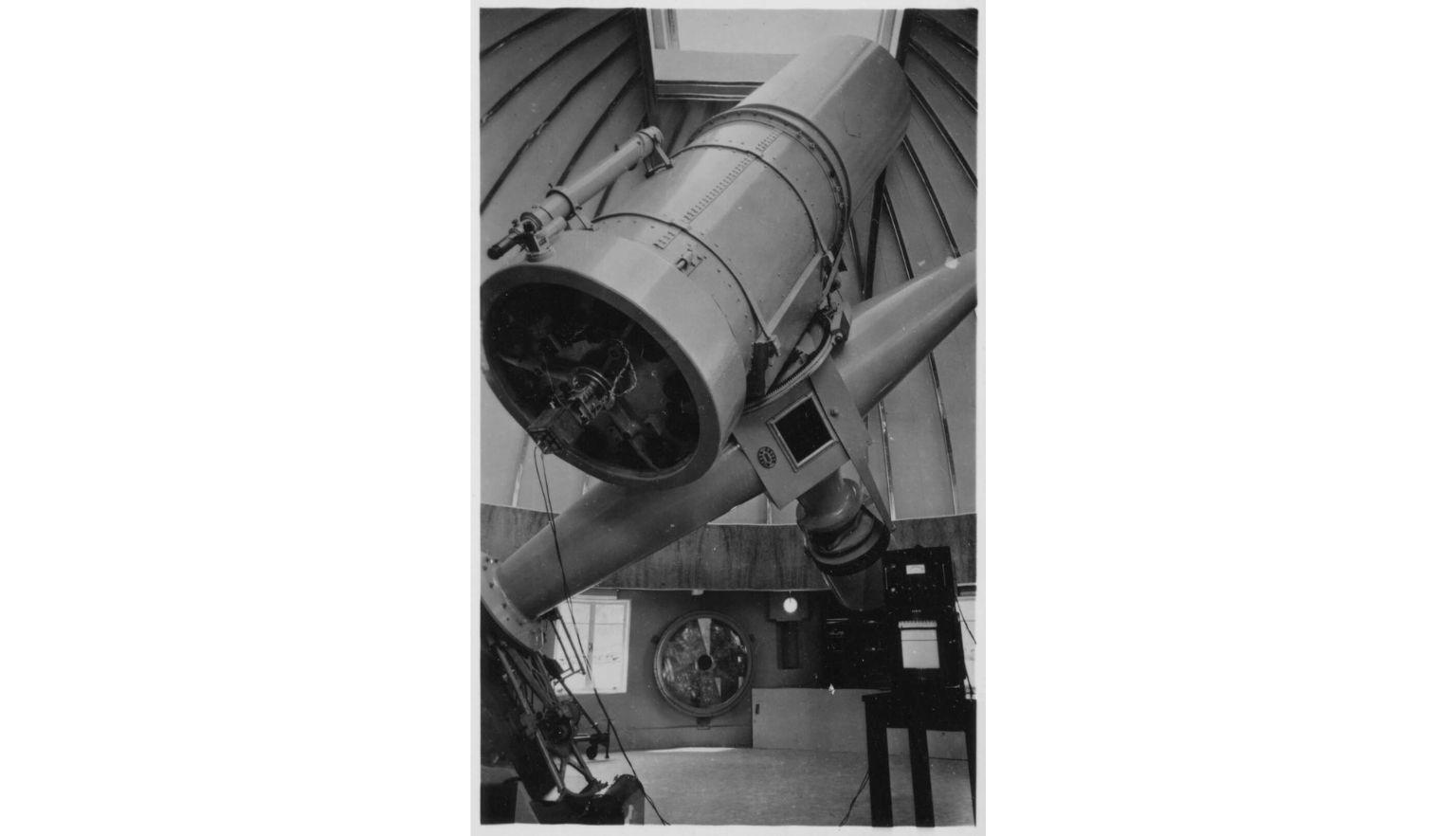

The Great Melbourne Telescope is another instrument with over 150 years of history. When installed in the Melbourne Observatory in 1868, it was the second largest optical telescope in the world and the largest telescope that could be fully steered. It was moved to the Mount Stromlo Observatory in 1945, where it underwent further upgrades to keep pace with ever-changing technical requirements. It was still in use at Mount Stromlo until 2003, when it was damaged in the Canberra bushfires.

Its destruction is a reminder that exploring the universe requires listening to the needs of this planet as well. Nevertheless, the current efforts to restore it highlight the resilience and innovation that has driven the space industry in Australia for nearly two centuries.

D. Moore, Radio telescope, 210 foot, Parkes, New South Wales, October 1961, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-137743535

D. Moore, Radio telescope, 210 foot, Parkes, New South Wales, October 1961, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-137743535

Perhaps the most famous of Australia’s telescopes is the Parkes Observatory, known for its involvement in the moon landing and its starring role in the iconic film The Dish. Around 8 minutes after Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station in the ACT broadcast Neil Armstrong’s first steps, the moon came in range and the signal was transferred to Parkes for the remaining two hours of the broadcast.

Lesser known is the fact that the Parkes Observatory was also instrumental in reestablishing communication with Apollo 13 after its accident in 1970.

We weren't actually supposed to take part in that mission because the moon would have been below our, our horizon at the time… And then of course when it broke down halfway there was no communication with it until Parkes was brought into the network that night…

Stories like these highlight the essential part that Australian space technology has played in connecting the international community to the southern skies.

Past and future

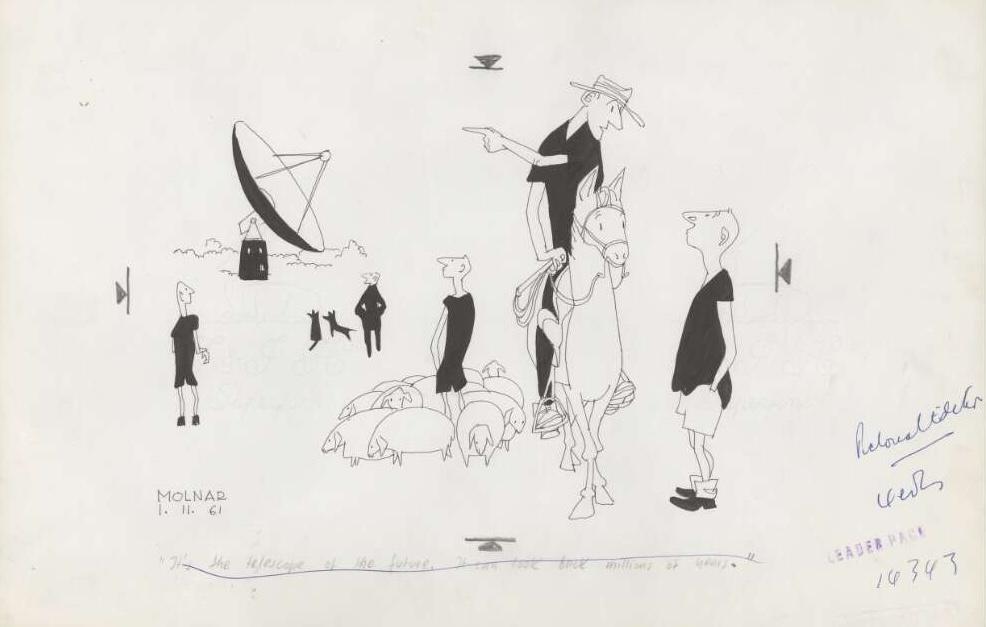

George Molnar, "It's the telescope of the future. It can look back millions of years.", 1961, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-147553167

George Molnar, "It's the telescope of the future. It can look back millions of years.", 1961, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-147553167

When looking through a telescope, you are seeing the light from stars from thousands of years ago. There is even more to discover when looking towards the future.

We can look into the future for a while, but life around us changing… you don’t do this in isolation. You’re always curious but also I think we’re so responsive.

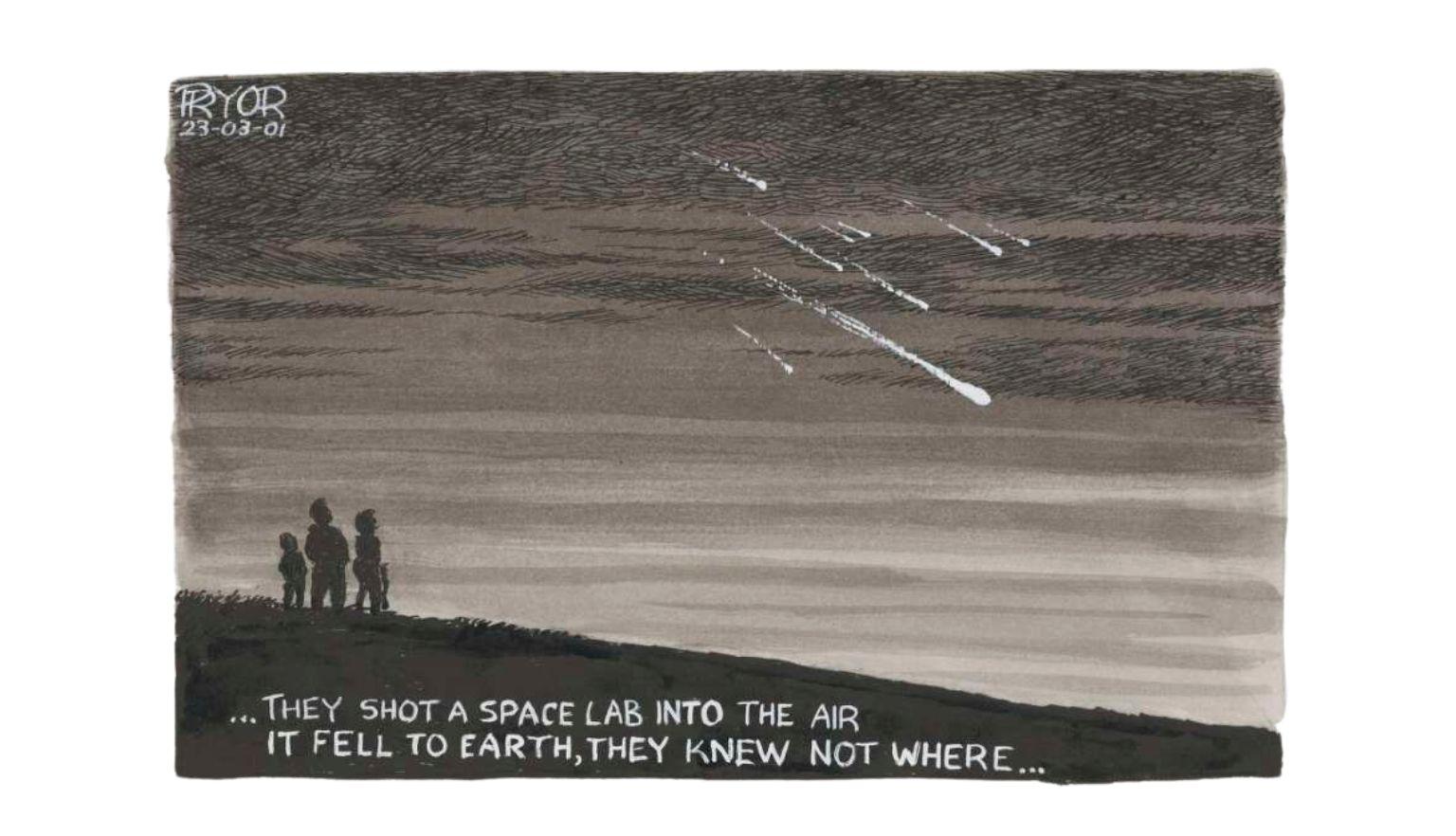

While you await the next appearance of Encke’s Comet – scheduled for February 2027 – why not discover more stories from the 1973 Australian astronomers oral history project, or listen in to where Australia’s space industry is heading with the ongoing Women in the space industry oral history project.

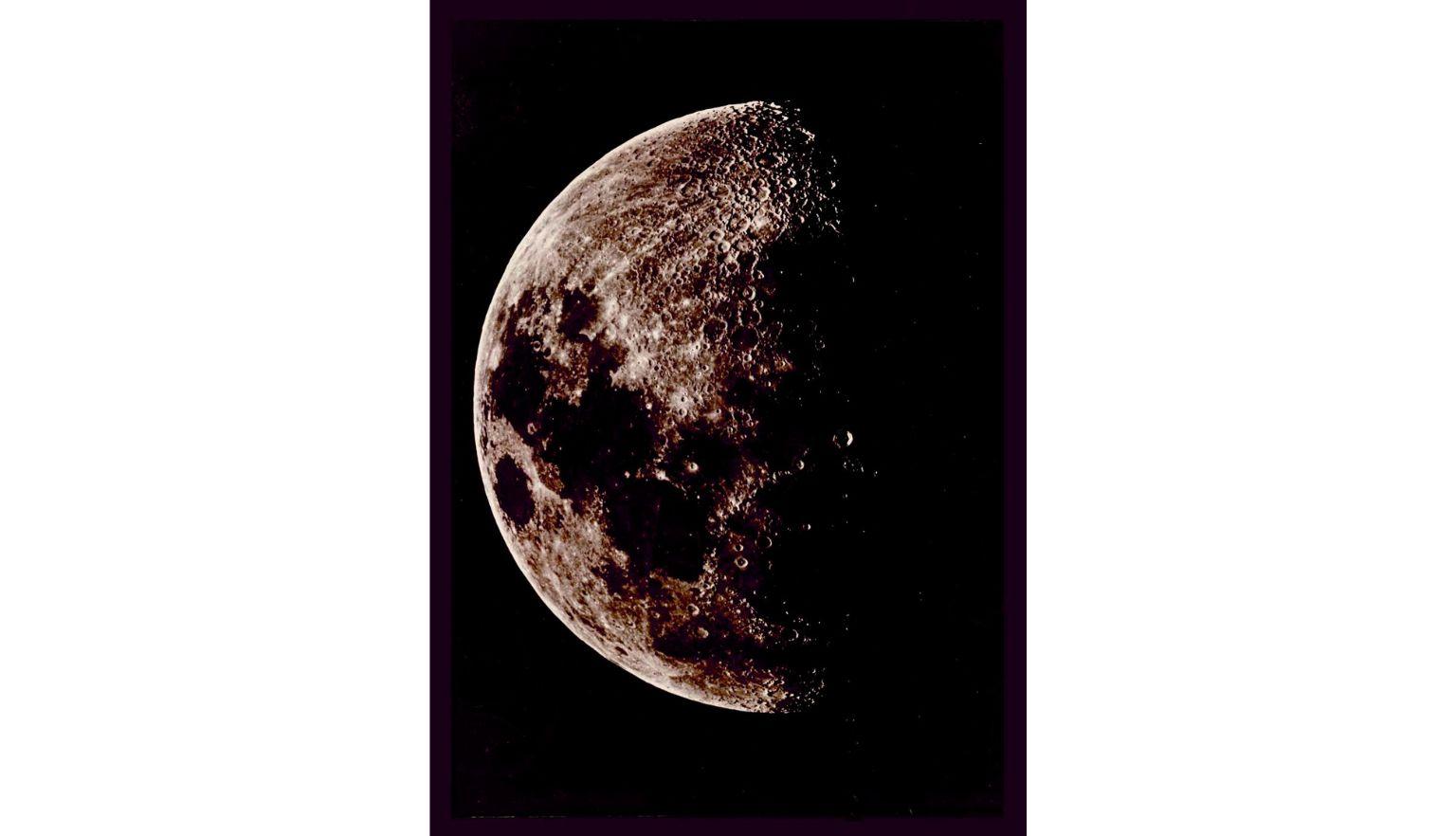

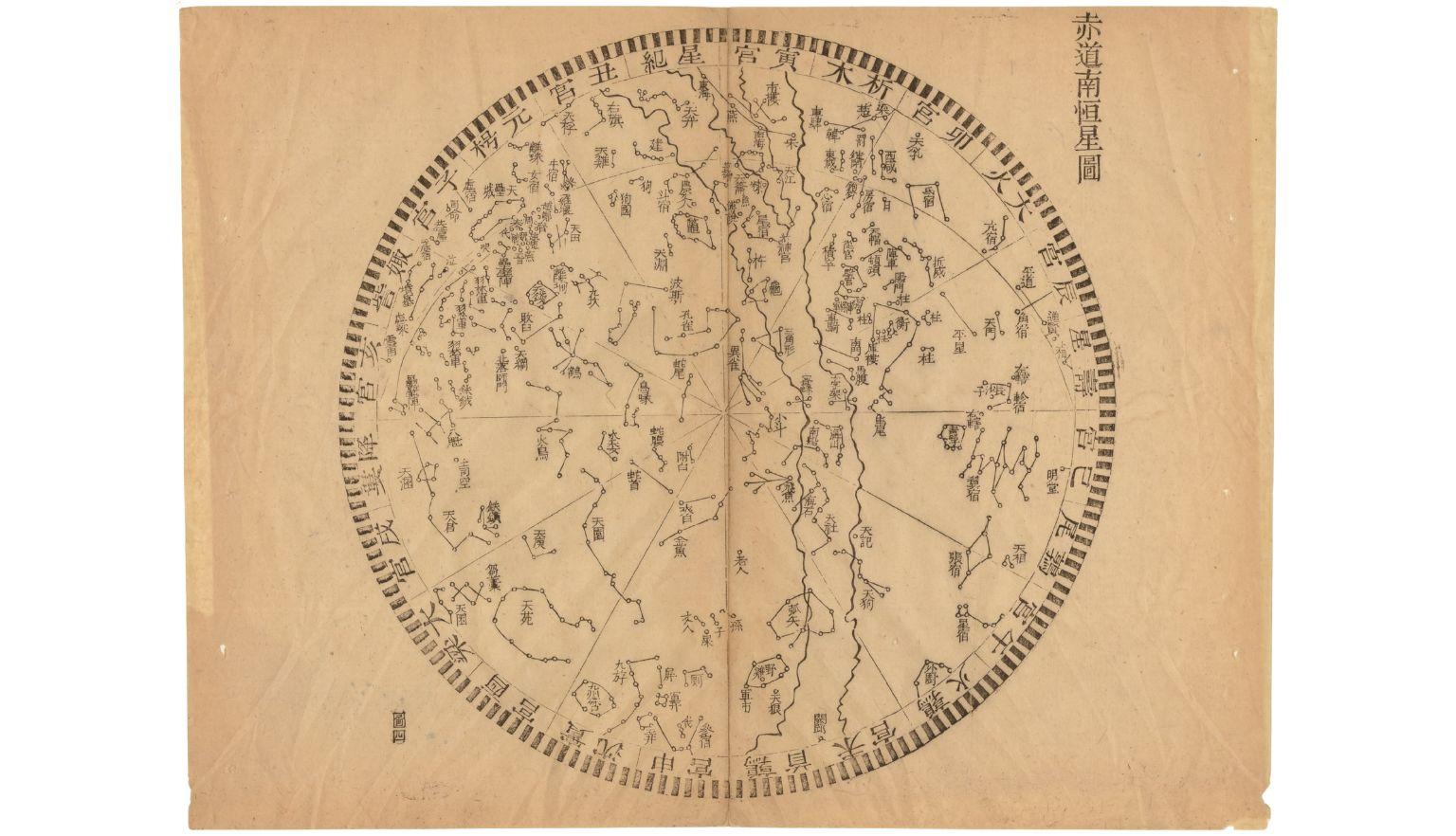

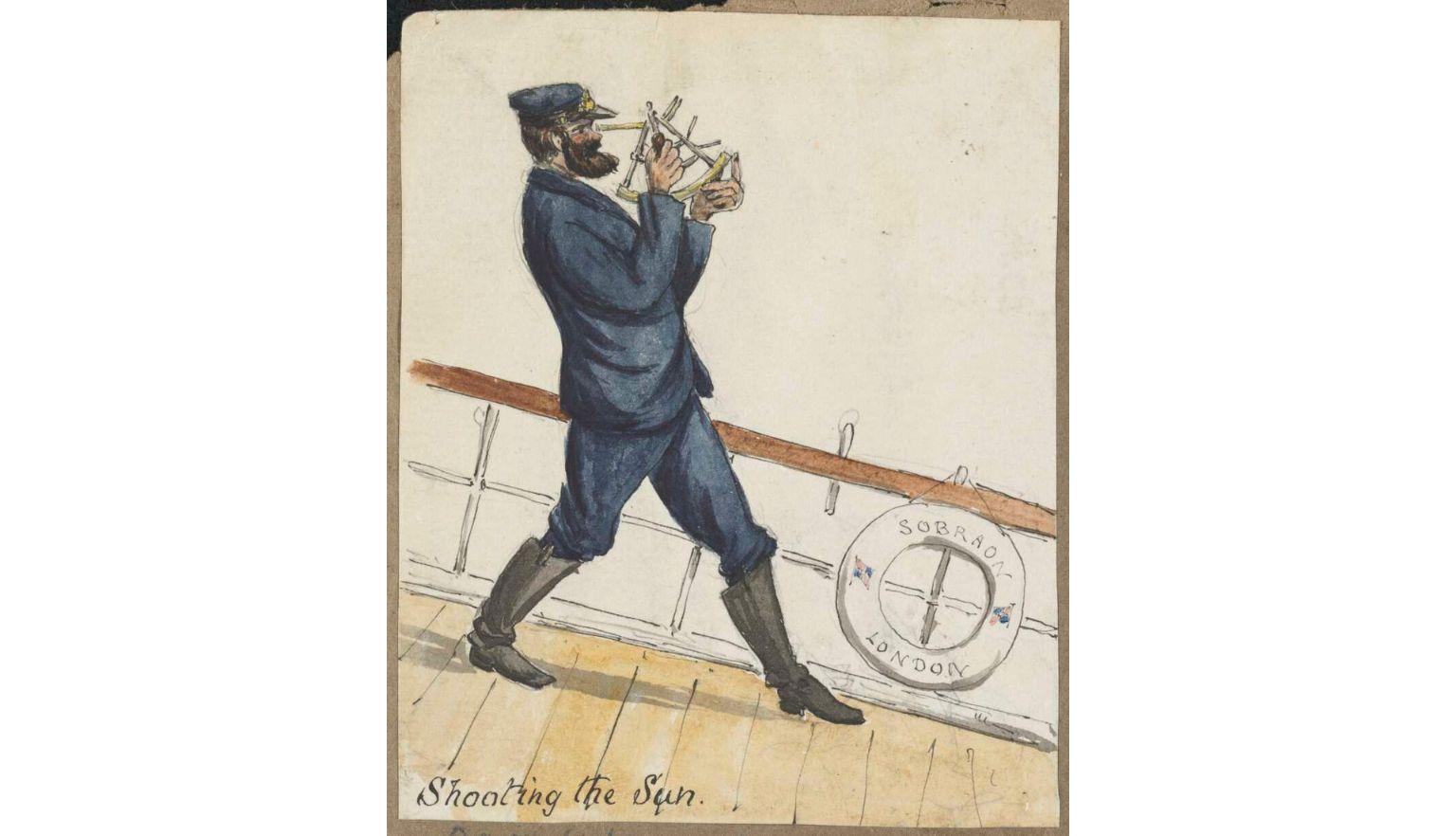

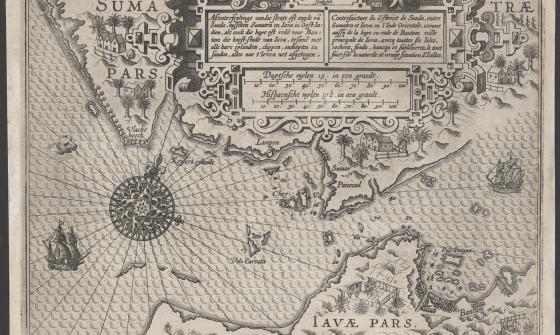

Alternatively, take a step back in time and follow our efforts to understand the southern skies through our collection of celestial maps, atlases, and astronomy texts from around the world.

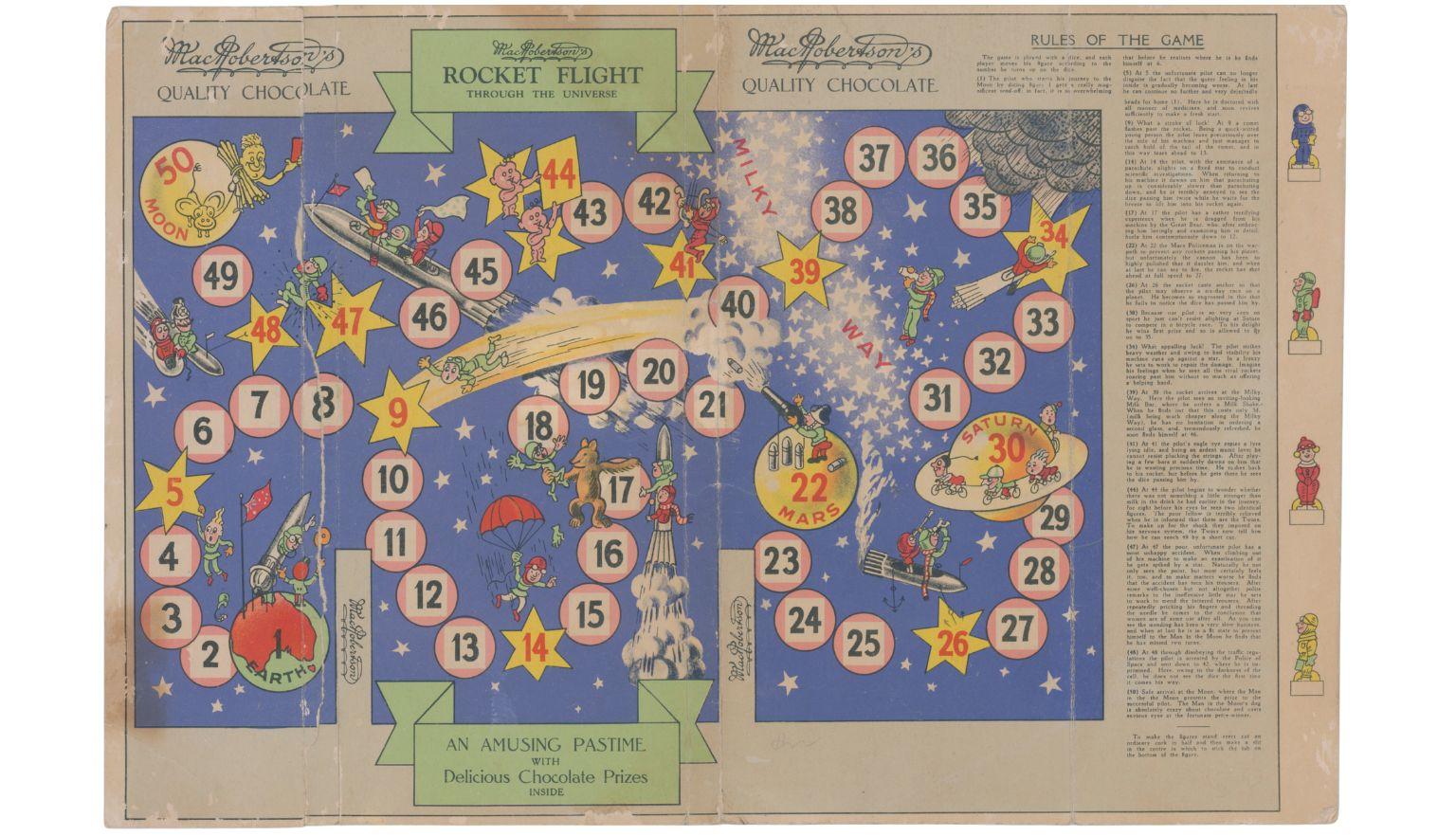

There’s also much more to explore in our digital collection from the many millennia of astronomers, navigators, artists, photographers and even the intrepid board-gamers who have found themselves fascinated with the stars.