The decline of the Khmer Empire

During this time, the kings of Angkor sustained their empire with vast canal systems and enormous man-made lakes; honoured the spiritual realm with statues of gold and jewels; and built monumental temples celebrating their gods, ancestors and kin. It has been calculated that, combined, the monuments and buildings of Angkor used more stone than all the pyramids of Egypt.

Yves Coffin, [Wat Ek, comprehensive view, southern side], nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140371255

Yves Coffin, [Wat Ek, comprehensive view, southern side], nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140371255

However, like many great empires throughout history, the Khmer Empire eventually began to fracture. Internal unrest and growing external pressures gradually undermined its stability.

Signs of decline

By the time the Chinese envoy Zhou Daguan visited Angkor in 1296, the empire was already in decline. Following the reign of Jayavarman VII (1181–1218), there was a noticeable drop in new building projects and inscriptions. Records and artworks became rarer—an indication that the cultural and economic strength of the empire was fading.

Yves Coffin, [Preah Vihear, Library H, seen from the east], nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140370657

Yves Coffin, [Preah Vihear, Library H, seen from the east], nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140370657

Despite this, the Khmer Empire’s 629-year reign places it among the longest-lasting empires in world history.*

| Empire | Modern location of historical power centre | Approx. foundation | Approx. end | Total duration (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sumer | Iraq | 4500 BCE | 1900 BCE | 2600 |

| Byzantine Empire | Turkey/Greece | 330 CE | 1453 CE | 1123 |

| Ghanaian | Mali | 300 CE | 1240 CE | 940 |

| Holy Roman Empire | Central Europe/Germany/Italy | 962 CE | 1806 CE | 844 |

| Zhou Dynasty | China | 1046 BCE | 256 BCE | 790 |

| Khmer | Cambodia | 802 CE | 1431 CE | 629 |

| Ottoman | Turkey | 1299 CE | 1922 CE | 623 |

| Dutch | The Netherlands | 1568 CE | 1975 CE | 407 |

| British | England | 1603 CE | 1997 CE | 394 |

| Russian | Russia | 1721 CE | 1917 CE | 196 |

*This list is not exhaustive.

External threats

From the 13th century, the kingdom faced mounting threats from its neighbours. In the west, the Thai kingdoms of Sukhothai and Ayutthaya were growing stronger, launching increasingly frequent raids into Khmer territory. These incursions disrupted trade and undermined the safety of the empire’s borders.

In the north, the kingdom of Lan Xang (in modern-day Laos) also became more aggressive. Repeated military campaigns unsettled the population, and over time, people began to migrate away from Angkor in search of greater safety.

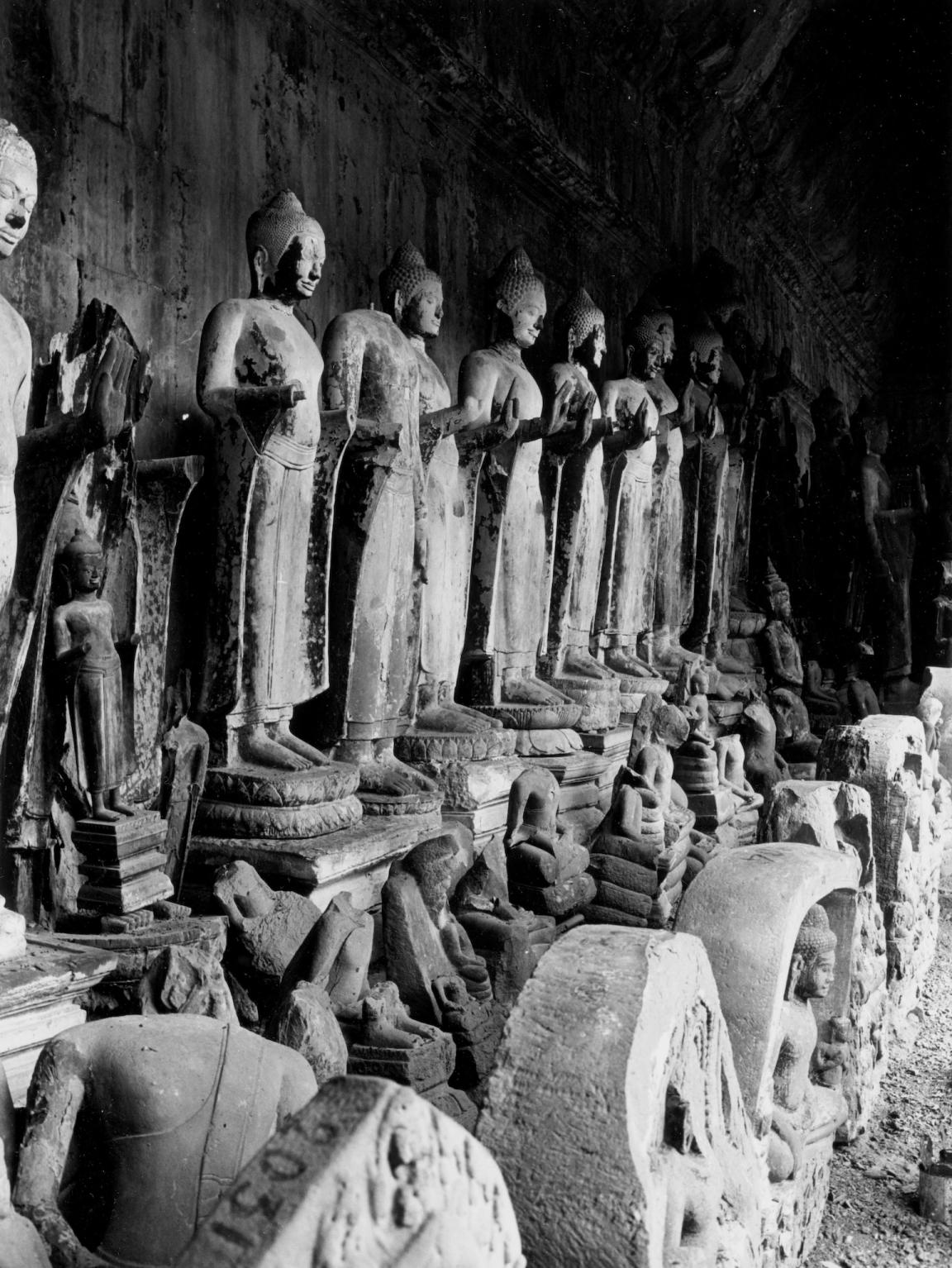

Yves Coffin, [Angkor Wat, Buddhas], nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140371553

Yves Coffin, [Angkor Wat, Buddhas], nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140371553

Environmental change

Environmental factors likely played a key role in the decline of the Khmer Empire. Some historians connect the empire’s fall with the arrival of the ‘Little Ice Age’, a period of rapid climate change that began around 1300 CE, following the warmer and more stable Medieval Warm Period.

In Europe, this climate shift brought freezing rivers and poor harvests. In South-East Asia, the effects were equally severe. The regular wet–dry seasonal pattern became erratic. Years of drought were followed by heavy, destructive rainfall. This climatic instability made traditional Khmer rice farming less reliable.

To compensate, farmers cleared more forest for fields. But this had unintended consequences: when the rains returned, sediment that had once been held in place by forest trees now flowed into the barays. These great reservoirs, along with the canals and dykes that fed them, began to clog with silt.

Some scholars believe that, by the end of the empire, so much sediment had accumulated that many barays and canals were no longer functional. With reduced food production and a shrinking workforce, it became harder to repair and maintain the water system—a system on which Angkor depended for survival.

Internal pressures and religious change

The Khmer Empire also faced internal divisions. For centuries, the people had practised a blend of Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism, philosophies that supported ancestor worship, royal cults and social hierarchy.

Over time, however, there was a major religious shift toward Theravada Buddhism, a belief system that emphasised simplicity, personal reflection and social equality. This presented a challenge to the traditional class structure and divine authority of the kings. Tensions grew between the spiritual ideals of Theravada and the rigid structures of royal power.

Yves Coffin, [Tep Pranam, Buddha], nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140372004

Yves Coffin, [Tep Pranam, Buddha], nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140372004

Final collapse

In 1353, Angkor was conquered by Thai forces, who briefly set up a government in the city. Although the Khmer regained control, repeated attacks by Ayutthaya and other Thai kingdoms led to further destruction. The city was sacked and burned multiple times. Raids from the Lan Xang in the north continued to weaken Khmer control of its provinces.

The final blow came in 1431, when the Thais laid siege to Angkor and captured it once more. With trade routes disrupted and the capital in ruins, many residents abandoned the city. What remained of the Khmer court moved south to present-day Phnom Penh.

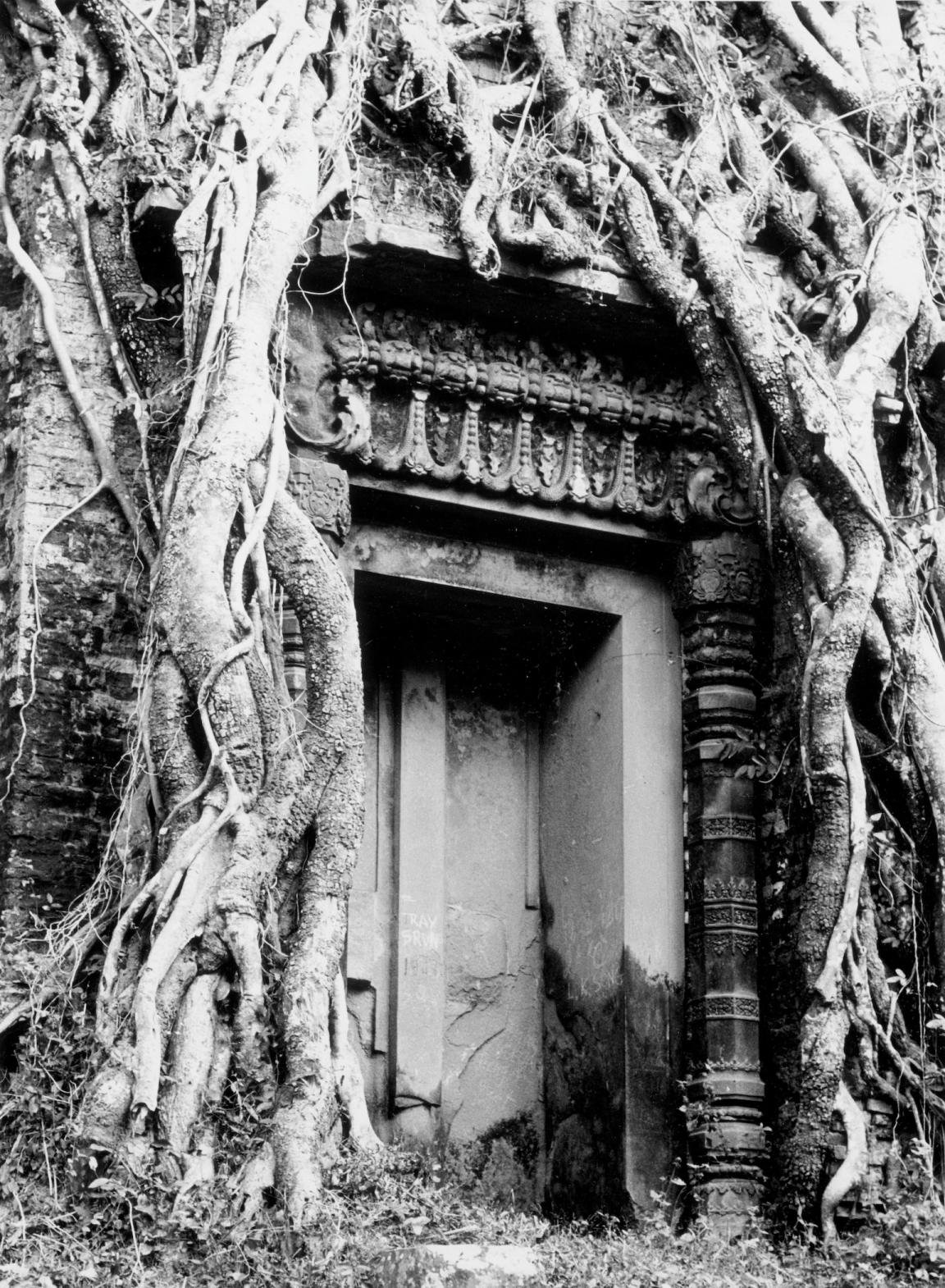

Yves Coffin, [Sambor Prie Kuk, view of false door on western side of temple], nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140373054

Yves Coffin, [Sambor Prie Kuk, view of false door on western side of temple], nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140373054

Following the move, there was a marked decline in the political, military and cultural influence of the Khmer Empire. Though the memory of Angkor lived on, the city itself faded from prominence.

Learning activities

Activity 1: Explore the effects of religious change on power

Research the core beliefs of Theravada Buddhism. How might a shift toward these beliefs have challenged the power and position of the Khmer royal court? Think about how a new belief system could change the way people view rulers and government.

Activity 2: Investigate how climate may have caused collapse

Some historians argue that a change in climate contributed to the downfall of the Khmer Empire. How could a long period of drought or flooding affect an empire that depended on farming and complex water systems? Make a list of the possible impacts on food, society and leadership.

Activity 3: Connect past climate change to other empires

The Earth’s climate has gone through natural changes many times in history. Research another ancient empire that declined during a major climate shift. What happened to it? What reasons have been suggested for its collapse?

Activity 4: Think about the future of food and climate

Today, the climate is changing faster than at any other point in human history. What could this mean for future food production and stability around the world? Write a short paragraph predicting some of the risks we might face if the climate continues to change.

Activity 5: Imagine the loss of a capital city

Imagine Canberra suddenly disappears and everyone who lived and worked there has to leave. What problems would this cause for Australia? How would the government continue to run? What would happen to the economy? How would people in other cities be affected? Write your ideas as a short response or discuss them as a class. You could also apply this activity to a state or territory capital instead.