Building Angkor

Monumental temples and royal power

Like Indravarman I, many began building temples, shrines and public buildings almost immediately after ascending the throne. These buildings were often dedicated to gods or the king’s ancestors. Constructing temples was a way to show piety and continue the cult of the king’s divine status. Monument building was both a spiritual and political statement.

Architecture and materials

Most Khmer buildings and houses were made of wood with thatched roofs. Stone walls and tiled roofs were expensive and generally reserved for high-ranking officials and the royal court.

By building magnificent stone temples decorated with intricate carvings, a king could proclaim his power and wealth. These structures also ensured the king’s name would live on after death.

Wooden buildings decayed quickly in the warm, humid climate of Angkor, while stone structures endured. Today, only the stone buildings remain. These often feature sculptures and carved texts that record the deeds of the kings who built them, but little evidence of daily life for the lower classes survives.

Yves Coffin, [Angkor Wat, perron of main temple and sculptures], nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140376052

Yves Coffin, [Angkor Wat, perron of main temple and sculptures], nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140376052

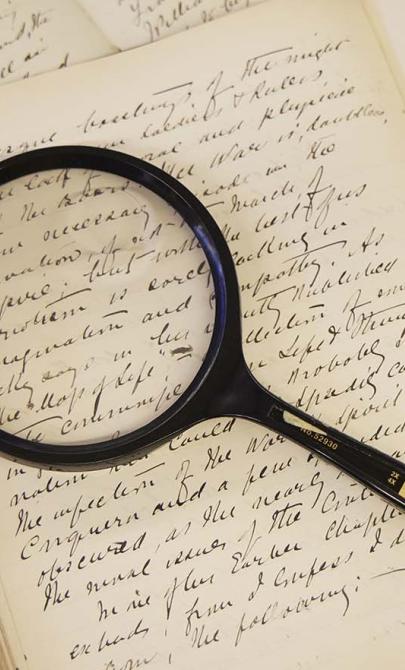

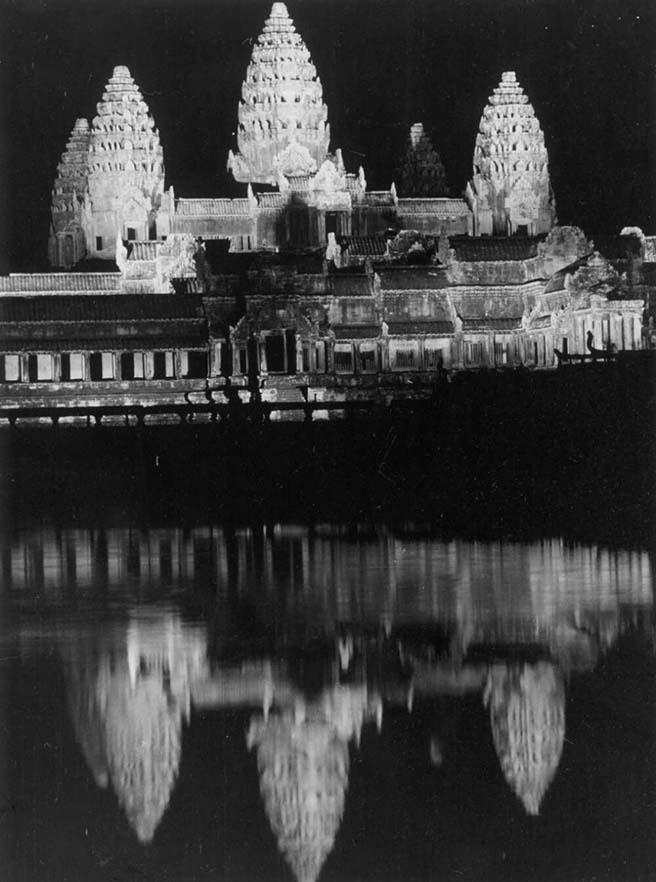

Angkor Wat

The most iconic structure from the Khmer Empire is Angkor Wat (meaning City-Temple). Commissioned by Suryavarman II (1113–1150) in the early 12th century, it was originally his state temple and personal mausoleum. It was later dedicated to the Hindu god Vishnu and eventually became a Buddhist place of worship toward the end of the Angkor period.

Yves Coffin, [Angkor Wat, view of main temple from western side], nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140376204

Yves Coffin, [Angkor Wat, view of main temple from western side], nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140376204

Angkor Wat is located in the south-east of the city built by Yasovarman I. Like many official structures of the time, it features striking symmetry. Its three main towers are intricately carved, with the central tower being the tallest. The temple buildings and galleries are surrounded by a series of walls.

Yves Coffin, [Angkor Wat, aerial view from the south-west], nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140375907

Yves Coffin, [Angkor Wat, aerial view from the south-west], nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140375907

This style of construction is known as temple-mountain architecture. The temple symbolises Mount Meru, the mythical home of the gods in Hindu cosmology.

The outer wall of Angkor Wat measures nearly four kilometres in perimeter. Today, the space between the inner and outer walls is filled with grass and trees, but at its peak, it was part of the city—home to houses, markets and palaces.

Yves Coffin, [Angkor Wat, view of main temple at night], nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140373200

Yves Coffin, [Angkor Wat, view of main temple at night], nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140373200

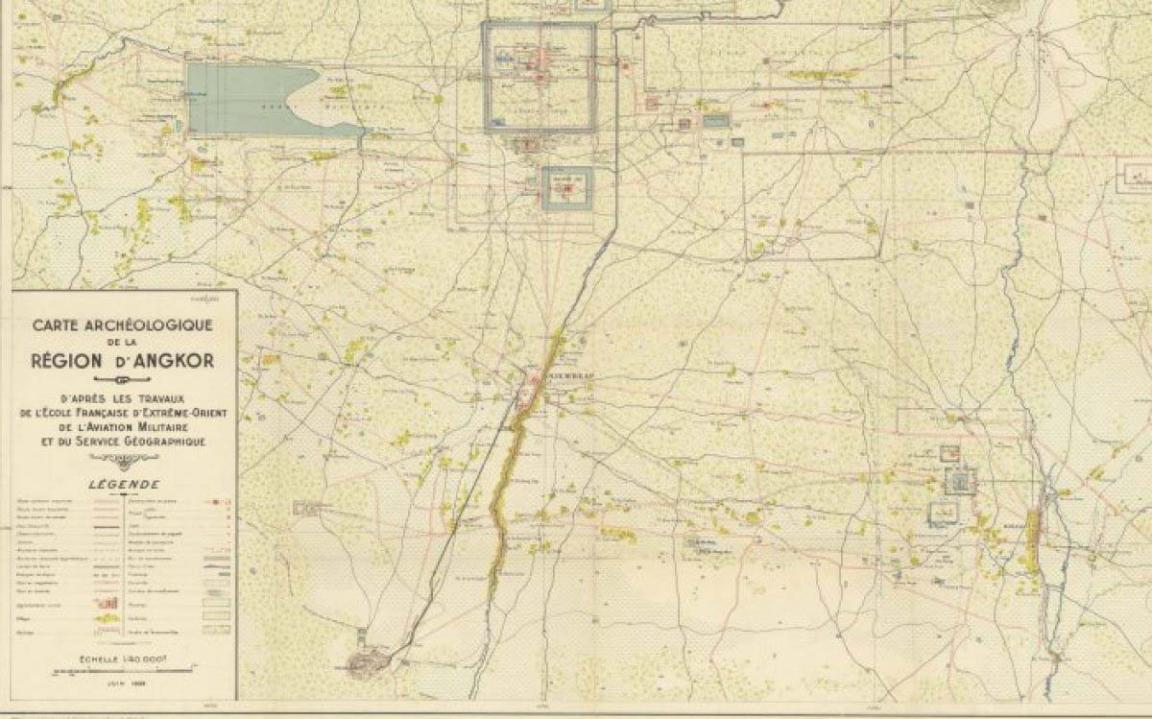

Archaeologists believe Angkor, along with neighbouring Angkor Thom, may have rivalled the largest cities in the world at the time, with estimated populations ranging from 750,000 to one million people.

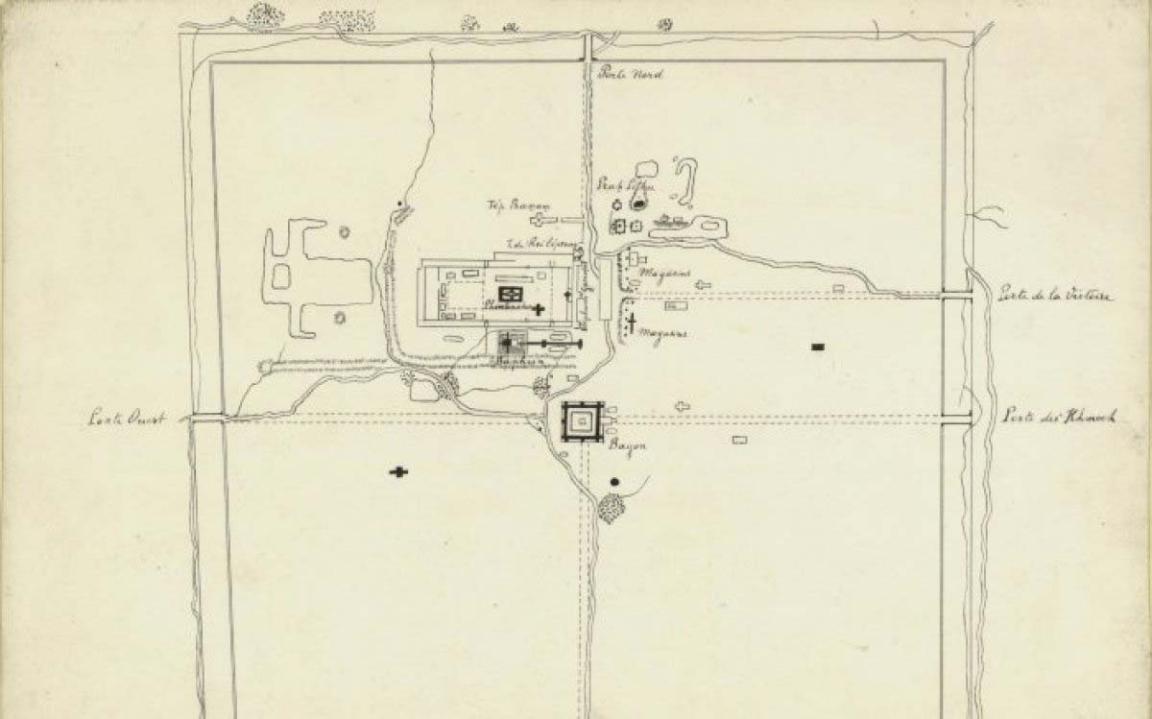

French Indochina. Service géographique. (1939). Carte archeologique de la region d'Angkor [cartographic material] / d'apres les travaux de l'ecole francaise d'Extreme -Orient de l'Aviation Militaine et du Service Geographique. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-2928032724

French Indochina. Service géographique. (1939). Carte archeologique de la region d'Angkor [cartographic material] / d'apres les travaux de l'ecole francaise d'Extreme -Orient de l'Aviation Militaine et du Service Geographique. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-2928032724

A square moat surrounds the entire temple complex, measuring 1.7 kilometres east to west and 1.5 kilometres north to south. It is almost 200 metres wide. A wide sandstone causeway links the temple to the mainland.

Angkor Wat has been a religious, spiritual and cultural centre since its foundation. It remains a powerful national symbol, featured on the Cambodian flag and recognised by royal decree.

Hydrology and public works

In addition to building temples, the Khmer kings were skilled engineers and hydrologists. Major cities throughout the empire included large-scale hydrological works such as reservoirs (barays), canals and sluices. Scholars are divided on whether these were primarily practical or spiritual in function.

An inscription from Preah Ko temple records a promise made by Indravarman I (877–889):

I will begin to dig five days from today [the day of his coronation].

He made good on this promise by building the Indratataka reservoir—a man-made lake 3.8 kilometres long and 800 metres wide. It could hold up to 7.5 million cubic metres of water (about three Olympic-sized swimming pools). Though dry today, the reservoir once supplied water to the capital, Hariharalaya.

During the monsoon, the reservoir collected excess water; in the dry season, the water was used to irrigate rice fields via channels and sluices. Later kings built even larger reservoirs. When Yasovarman I moved the capital to Yasodharapura (Angkor), he connected the old and new capitals with a waterway.

Reservoirs were built using huge labour forces drawn from the civilian population. The Khmer built strong earthen dykes from clay and soil dug from within the reservoir site. They even diverted rivers to fill the barays.

The Western Baray and West Mebon

The largest baray built during the Angkor period is the Western Baray. It dwarfs earlier efforts, measuring 8 kilometres by 2 kilometres (16 square kilometres) and holding about 53 million litres of water—roughly 21 Olympic swimming pools. It remains one of the largest hand-built bodies of water in the world.

(1901). [Angkor Thom, Cambodia]. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-234588572

(1901). [Angkor Thom, Cambodia]. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-234588572

At its centre is West Mebon, a small temple built in the 11th century by Udayadityavarman II. When the reservoir was full, the temple became an island. It was dedicated to the Hindu god Vishnu.

In 1936, archaeologists uncovered fragments of a colossal reclining bronze statue of Vishnu from the site.

Scholars believe that when the statue was intact, the temple would have appeared to show Vishnu reclining on the waters of the lake—symbolising the primordial ocean from which the gods created life. This symbolism has fuelled academic debate over whether the barays were spiritual, practical or both.

The legacy of Khmer engineering

For many Khmer rulers, building monuments and managing water resources were central to their rule. Kings known for effective infrastructure projects are often remembered as the most capable.

The building of monuments dedicated to the gods and ancestors, as well as managing the vast water resources of the kingdom was a major platform for many Khmer rulers.

Learning activities

Activity 1: Explore why the Khmer built on a grand scale

Khmer rulers placed great importance on large-scale building projects. Why do you think they invested so much in these constructions? What might these buildings have represented? Can you think of other ancient empires that also used large building projects to show their power or influence?

Activity 2: Solve a water crisis in Angkor

The canals and reservoirs (barays) of Angkor were massive engineering achievements. How would keeping these water systems running smoothly have helped a king to rule well? Imagine you’ve just become king and discover that many of the canals are blocked, the reservoir is leaking, and the sluice gates are broken. In a month, there will be no water left in the Western Baray. What problems might this cause for your people and your rule?

Activity 3: Find traces of ancient canals and barays

Use the map provided (Carte archéologique de la région d’Angkor, 1939) and compare it with a satellite view using an online map service. Search for Angkor Wat or use the coordinates 13.412007, 103.866856. What signs of the old canal systems can you still see from above? Can you find any disused barays? What do these features tell you about how the Khmer people managed water?

Activity 4: Walk through Angkor Wat and write from a visitor’s perspective

Use an online map service to explore the grounds of Angkor Wat at ground level. Walk through the temple complex and imagine what it would have been like to visit the city when it was still thriving. Write a short creative piece describing your experience. What do you see? What are the sounds and smells? How do you feel standing in front of such an impressive structure? Use historical terms where you can.