The way of life in the Khmer Empire

What we know — and what we don't

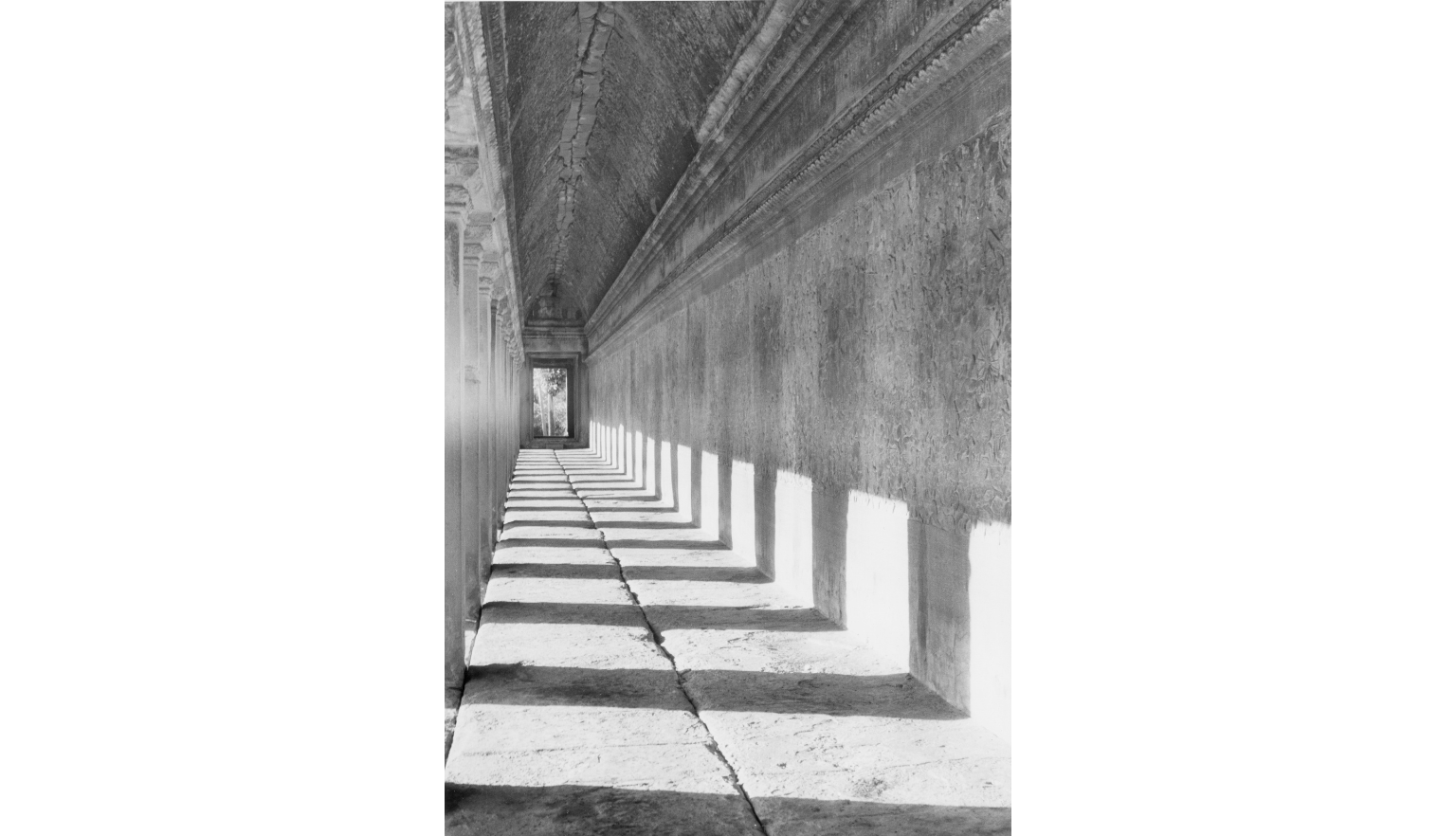

For all its splendour, there is very little primary source information relating to the day-to-day life of the people or the workings of government. Most of what modern scholars know of life at Angkor comes from the stone carvings found on temple walls.

During the Khmer Empire, records were kept on paper made from leaf fibres, rice paper or vellum. The climate of Cambodia is tropical, with hot humid summers and only slightly less humid winters.

Without proper preservation and storage, fibrous material such as wood, leaves and paper are susceptible to decay in these conditions. As such, the paper-based administrative records of the Angkor empire no longer exist. This leaves large gaps in our knowledge of what daily life was like in the empire.

What scholars do know about the day-to-day life of the Khmer people comes from foreign visitors to the kingdom.

The account of Zhou Daguan

The most well-known and comprehensive record of life in the Khmer Empire is that of Zhou Daguan. Zhou was part of a diplomatic mission sent to Cambodia by Temür Khan, the second emperor of the Yuan dynasty of China, in 1296. His account is believed to have been compiled sometime after his return to China, but before 1312. It was first transcribed from Chinese to French in approximately 1820. It was not translated into English until 1967.

Note: Zhou’s writing has been translated many times — sometimes from second-hand versions — which affects accuracy. Scholars continue to revise and reinterpret his descriptions.

The walled city

Zhou described the impressive city of Angkor Thom:

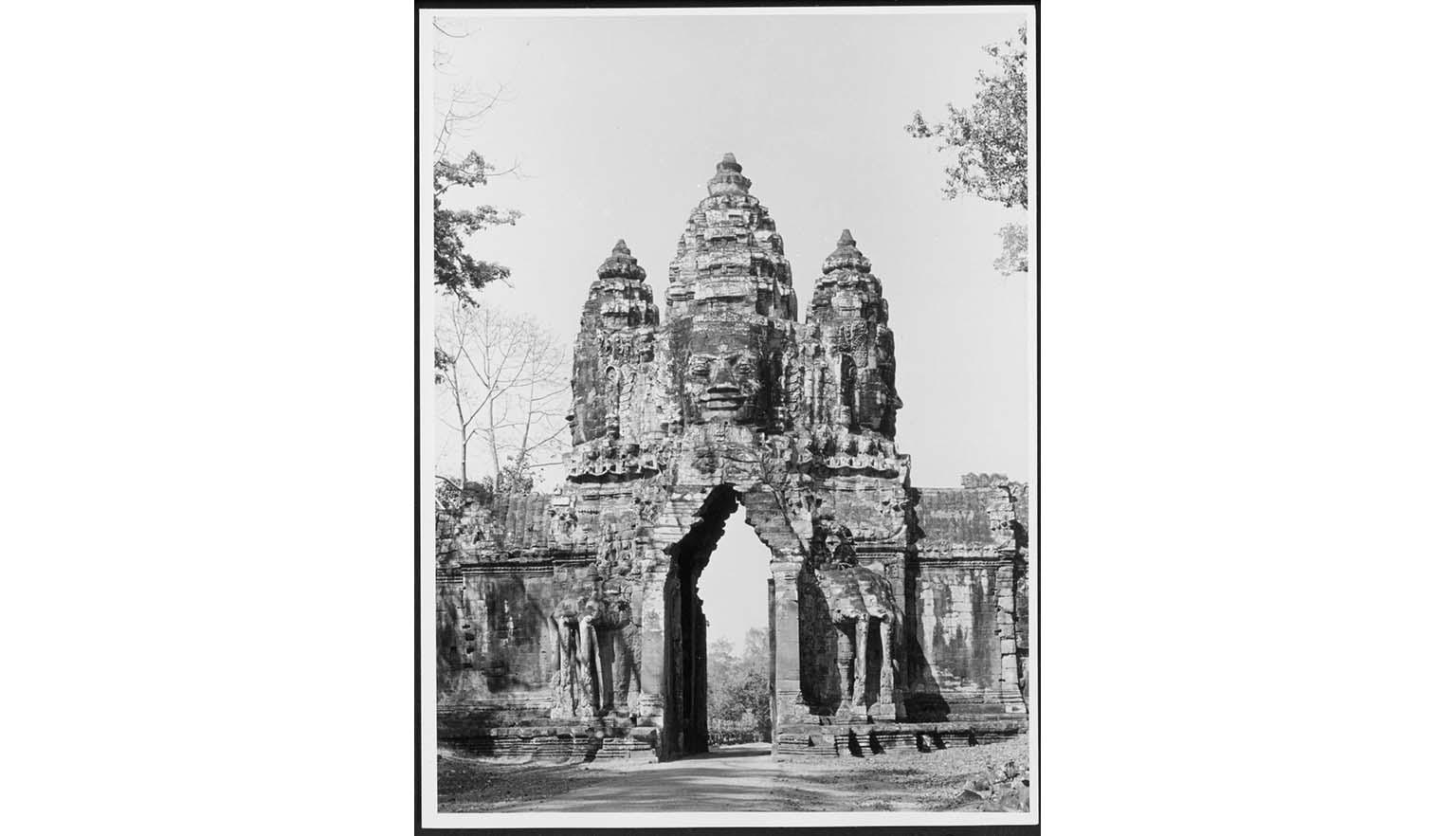

'The walls of the city are about twenty li in circumference. There are 5 gateways, each of them with 2 gates, one in front of the other.’

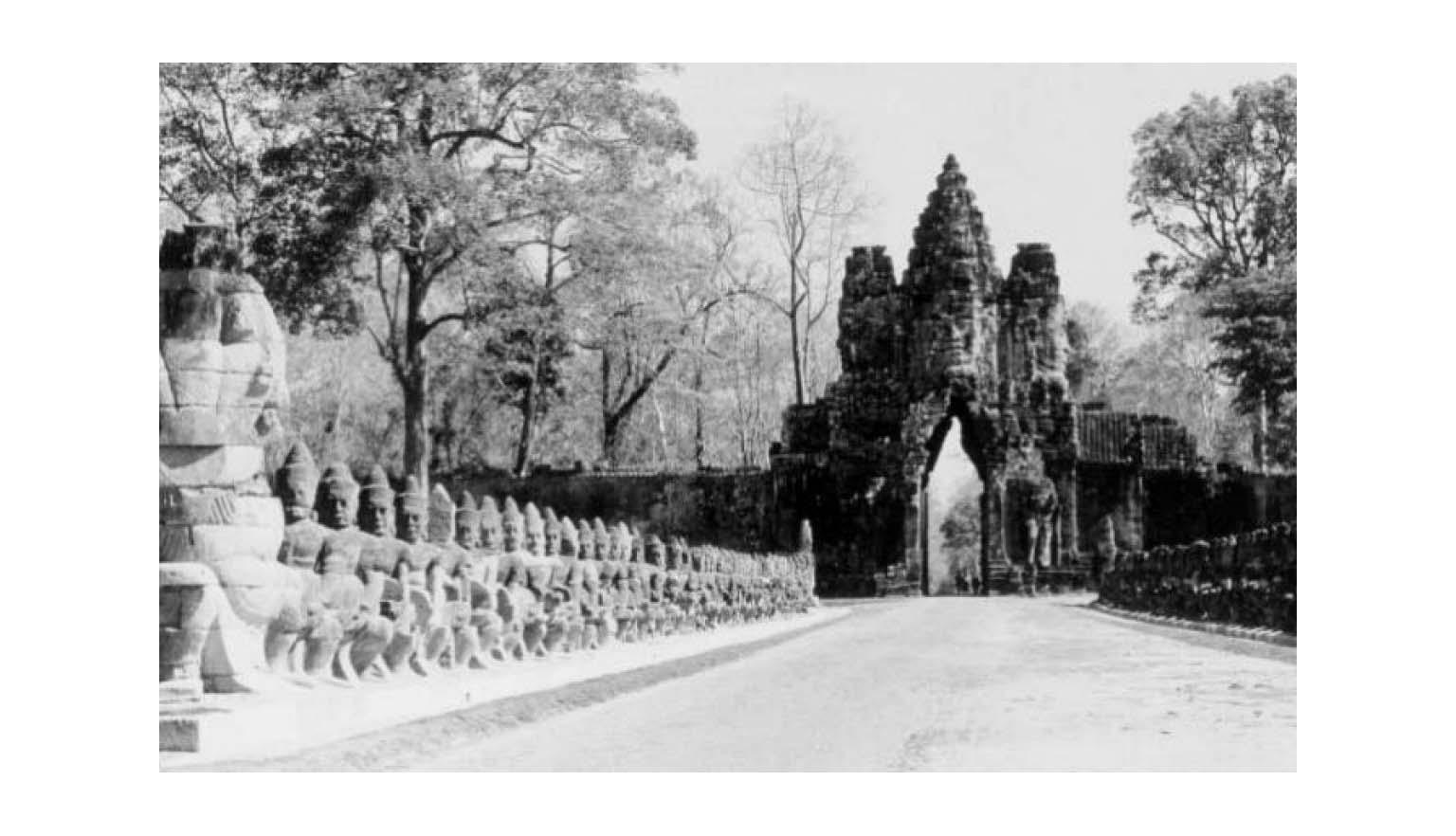

‘Around the outside of the city walls there is a very large moat. This is spanned by big bridges carrying large roads into the city.’

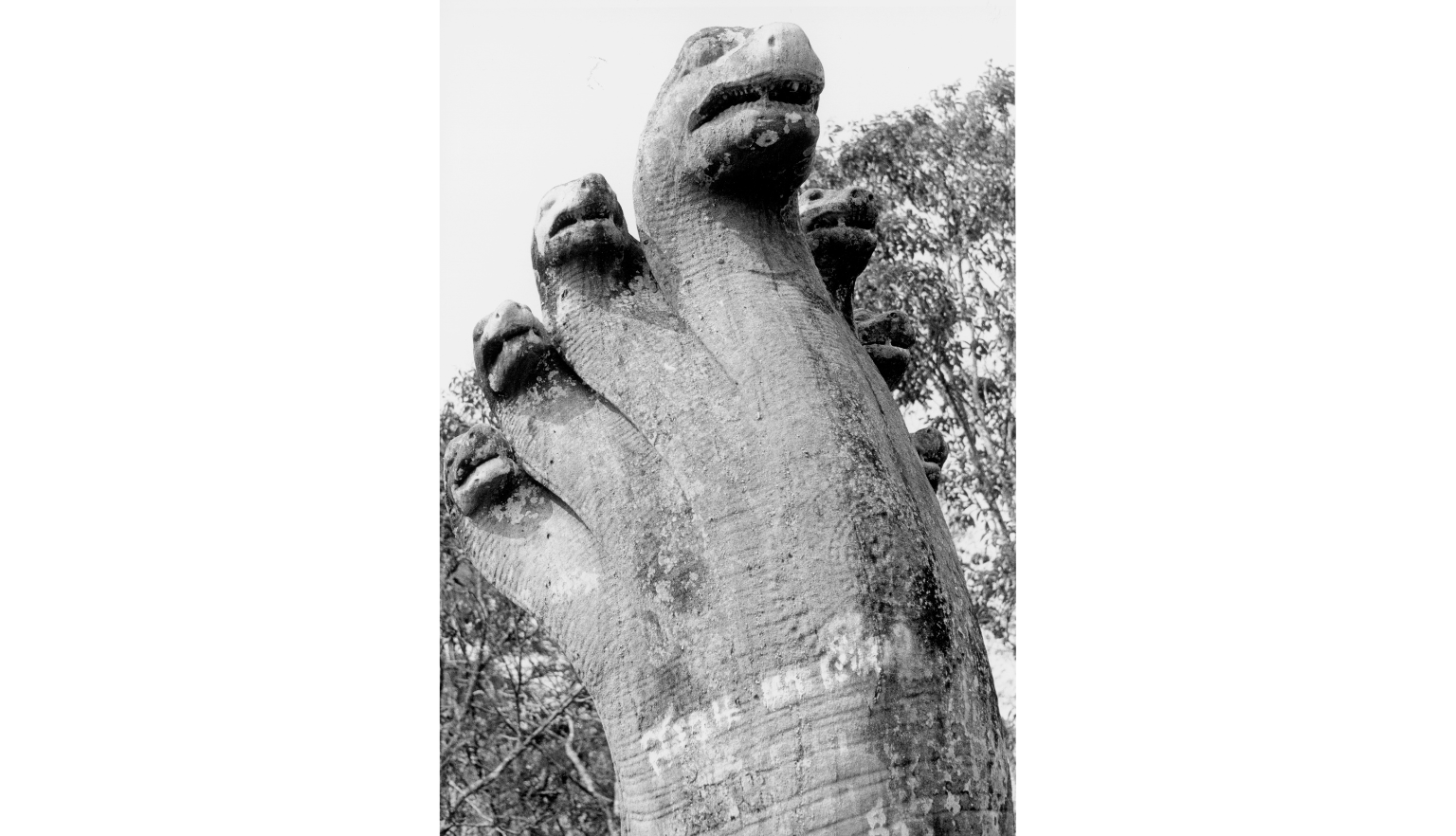

‘The five gateways of the city are all alike; the parapets of the bridges are all made of stone and carved into the shape of snakes, each snake with nine heads. Fifty-four deities are all pulling at the snake with their hands, and look as if they are preventing it from escaping.’

He also mentioned nearby landmarks:

‘Lu Ban Tomb [Angkor Wat] is about one li beyond the south gate. It is about ten li in circumference and has several hundred stone chambers.’

‘Ten li east of the city wall lies the Eastern Baray. It is about a hundred li in circumference. In the middle of it there is a stone tower with stone chambers. In the middle of the tower is a bronze reclining Buddha with water constantly flowing from its navel.’

Dwellings

Zhou noted major differences between royal and common homes:

‘The Royal Palace, officials’ residences, and great houses all face east. The Palace lies to the north of the gold tower with the gold bridge, near the northern gateway. It’s about five or six li in circumference.’

‘Inside the palace, there is a gold tower, at the summit of which the king sleeps at night. The local people all say that in the tower lives a nine-headed snake spirit which is lord of the Earth for the entire country.’

‘The dwellings of the king’s relatives and senior officials are large and spacious in style, very different from the ordinary people’s homes. The roofs are made entirely of thatch, except for the family shrine and the main bedroom, both of which can be tiled.’

‘The homes of the common people have roofs made only of thatch. They dare not put up a single tile. Although their houses vary in size depending how wealthy they are, they dare not build houses to rival the official residences.’

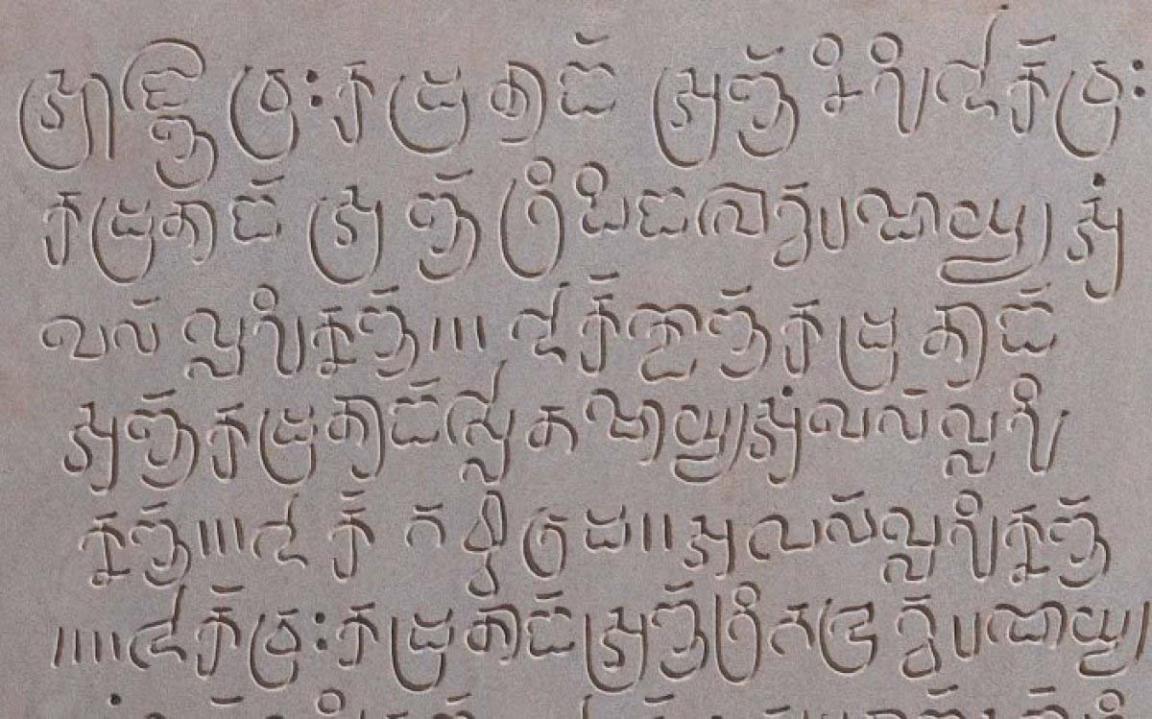

Writing

The Khmer people used a unique writing method:

‘Everyday writing and official documents are all done on the skin of muntjacs, deer, etc, that is dyed black.’

‘To write, people use a kind of powder like chalk, which is rolled into a little stick called suo. The markings can be erased using something wet.’

(2010). [Replica of Inscribed Khmer stele]. Siem Reap, Cambodia : [S.n.] nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn4823973

(2010). [Replica of Inscribed Khmer stele]. Siem Reap, Cambodia : [S.n.] nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn4823973

Trade

Zhou was impressed by the daily markets:

‘The local people who know how to trade are all women.’

‘There is a market every day from around six in the morning until midday. There are no stalls, only a kind of mat laid out on the ground. I gather there is a rental fee to be paid to officials.’

‘Market transactions for items of small value are paid for with rice or other grains. Higher value transactions are paid for with cloth. The largest transactions are done with gold and silver.’

Sought-after Chinese goods

Although Cambodia didn’t produce gold or silver, Zhou noted that Chinese imports were highly prized:

‘They do not produce gold or silver in Cambodia, I believe, and so they hold Chinese gold and silver in the highest regard..’

‘The people of Cambodia value items made of fine double-threaded silk in various colours. They also value such things as pewter ware from Zenzhou, lacquerware dishes from Wenzhou and celadon ware from Quanzhou.’

‘Beans and wheat are particularly sought after, but they cannot be taken there.’

Learning activities

Activity 1: Think about the limits of a single source

Zhou Daguan’s account is the only surviving eyewitness record of life in the Khmer Empire. It’s a vital source, but relying on just one account can be risky. What problems might come from using only one point of view? Make a list of possible issues that could affect how we understand the past.

Activity 2: Explore how language changes over time

Zhou wrote his report in Chinese in the late thirteenth century. While it’s still understandable today, some of the words and dialects he used have changed or disappeared over time. What problems could this cause when reading or translating his work? Discuss how meaning might shift over hundreds of years.

Activity 3: Investigate the effect of multiple translations

Zhou’s original text was translated into French in the 1800s, and later from French into English. How might these layers of translation affect the accuracy of the account? Try this for yourself: take a short quote from Zhou, paste it into Google Translate, and translate it into a different language. Then translate that result into another language before finally translating it back to English. Compare the final version to the original. What changed? What stayed the same? Does the meaning still hold?

Activity 4: Think about preserving information for the future

There are no surviving original Khmer documents — most were written on materials that didn’t last in Cambodia’s climate. Think about the materials we use to store information today. What conditions help things last over time? A lot of our information is now stored digitally. What problems might this cause in the future? What could we do to make sure digital data stays safe and accessible?