Dutch experiences in Australia

The MacRobertson Trophy Air Race

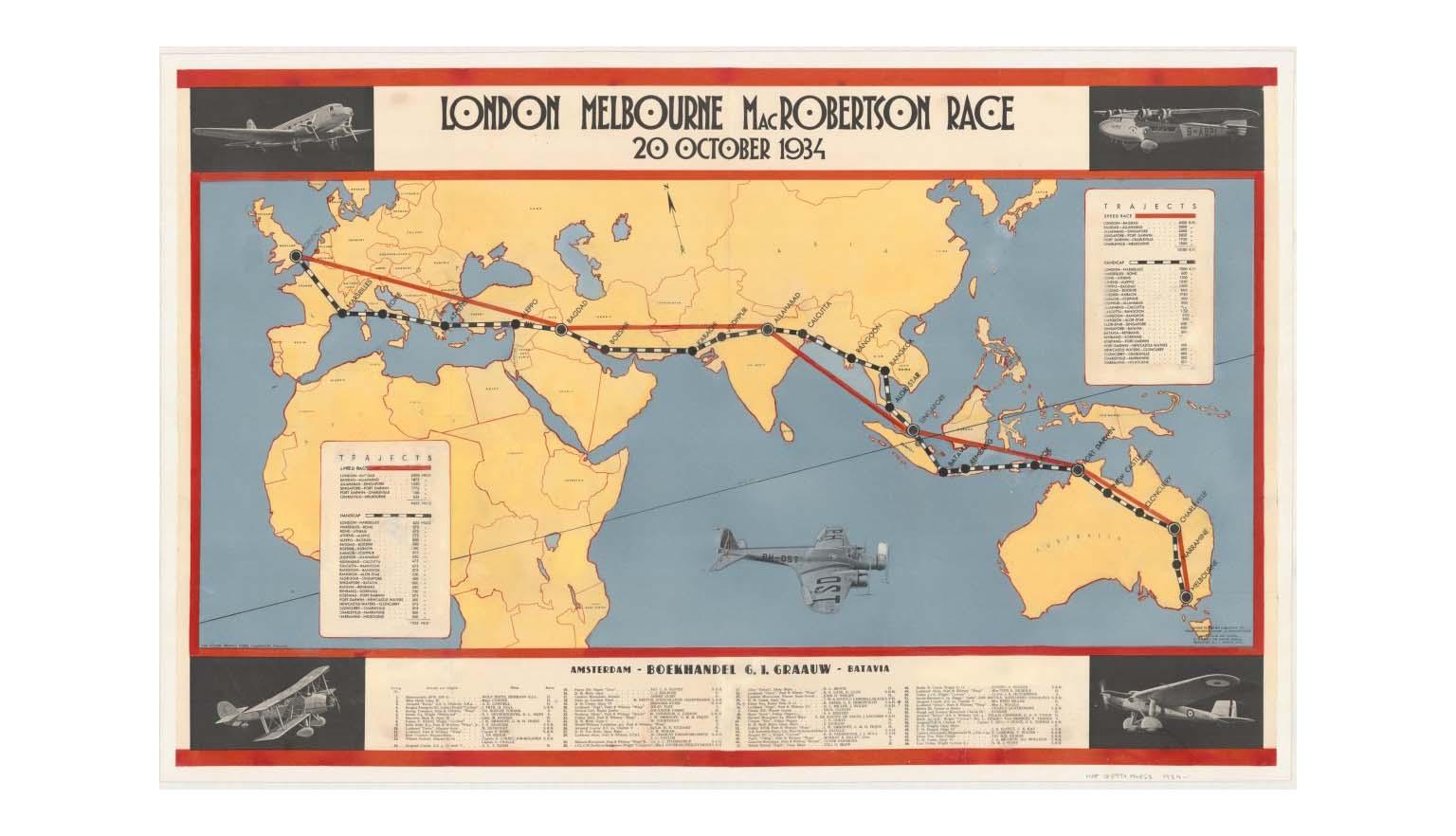

In October 1934, just 15 years since the first flight from London to Australia, Australian confectionery magnate and philanthropist Sir Macpherson Robertson sponsored an air race to commemorate the centenary celebrations of the state of Victoria.

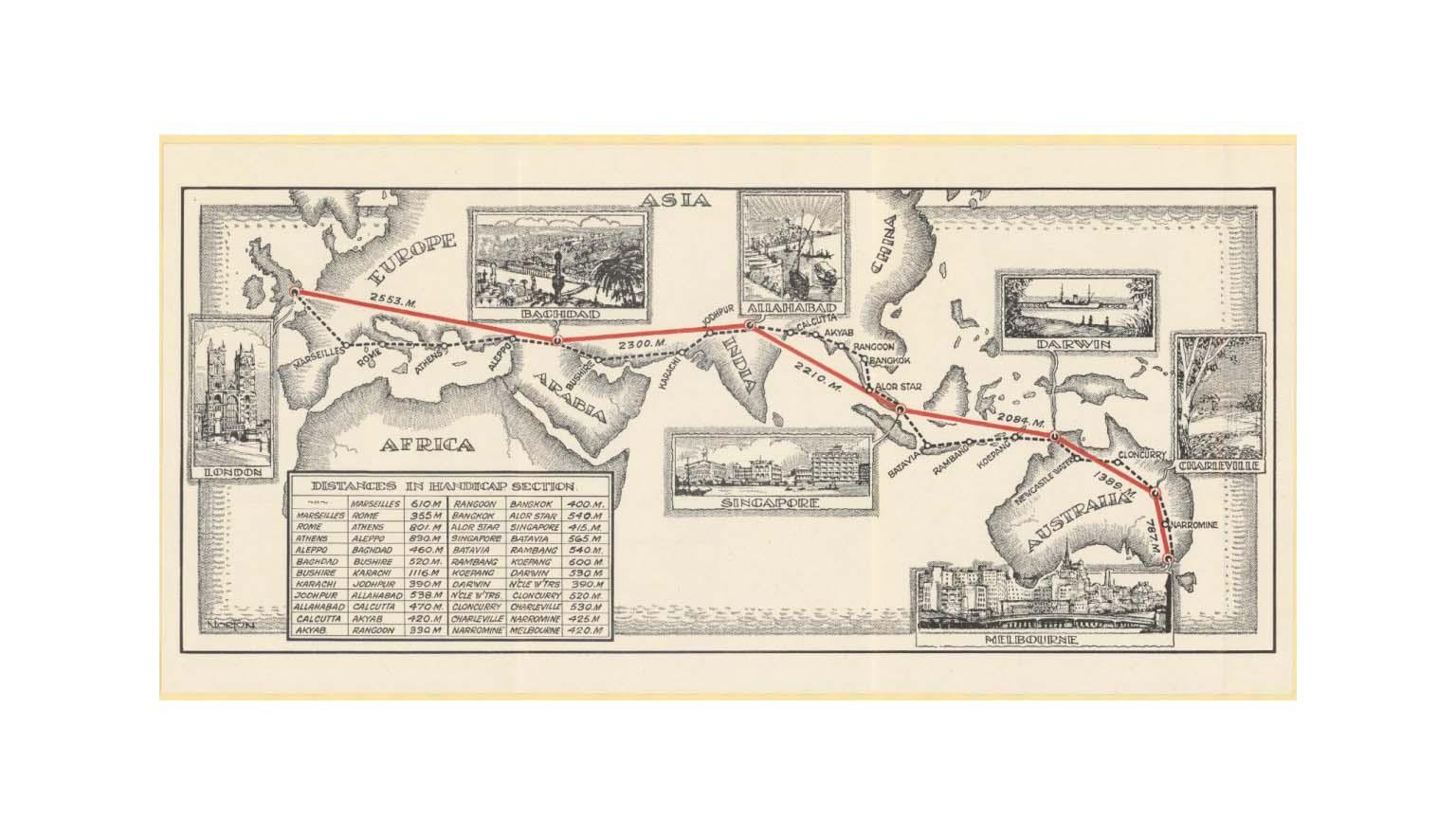

The MacRobertson Trophy Air Race, with a prize worth £15,000, attracted 20 entries from seven countries. Following the path featured in this map, contestants set out on a three-day journey from London to Melbourne. The race captured the attention of millions of people worldwide, who listened to wireless reports of the planes’ progress.

The Dutch entered the Uiver (the plane pictured above, meaning ‘Stork’), a DC2 newly purchased by KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, and took on three fare-paying passengers, alongside the four crew. Making good time and well positioned in second place, a thunderstorm threw the plane into chaos over southern New South Wales, disrupting communications and impeding the visibility of the crew. They were now in grave danger, low on fuel and flying in the rain across mountainous terrain. The world listened and waited on the edge of their seats.

Communities across Victoria and New South Wales rallied in the night to help guide the Dutch crew, listening for the plane and turning on their lights. Naval ships on the coast used searchlights to light the night sky.

Lyle Ferris, chief electrical engineer at the Albury post office, used the town’s entire streetlight system as a giant Morse code signal, messaging the name of the town repeatedly. Captain Parmentier and navigator Johannes Moll saw that message through the clouds, and the crew suddenly knew where they were. However, with no airstrip, Albury would not be a suitable place to land.

Albury radio announcer Arthur Newnham rose to this challenge. He encouraged all residents to flock to the racecourse, which they did, despite the late hour and pouring rain. Turning on their headlights in two rows, they formed between them a landing strip flooded with light.

With room to spare, the Uiver landed on the racecourse around 1.20am. The town celebrated, but the race was still on, and they also had more work to do to help the Dutch plane on its way. Three hundred townsfolk helped dig out the wheels of the plane, which were bogged in the mud, and worked together to lighten the load of cargo, excess crew and passengers. Having refuelled the Dutch plane, the townsfolk of Albury waved it on its way in the early morning. Arriving safely in Melbourne, the Uiver came second in the race and was declared the winner in the handicap category.

KLM made a large donation to Albury Hospital in gratitude for the town’s help. In a subsequent flight just two months later, the Uiver tragically crashed in the Syrian desert, killing all on board. The people of Albury collected donations to pay for a memorial in the Netherlands to the plane and its crew.

Post war Dutch migration to Australia

After World War II, the people of the Netherlands found themselves with a long journey ahead of them, resurrecting a war-ravaged country that was struggling to overcome recent famine and mass casualties in the Holocaust.

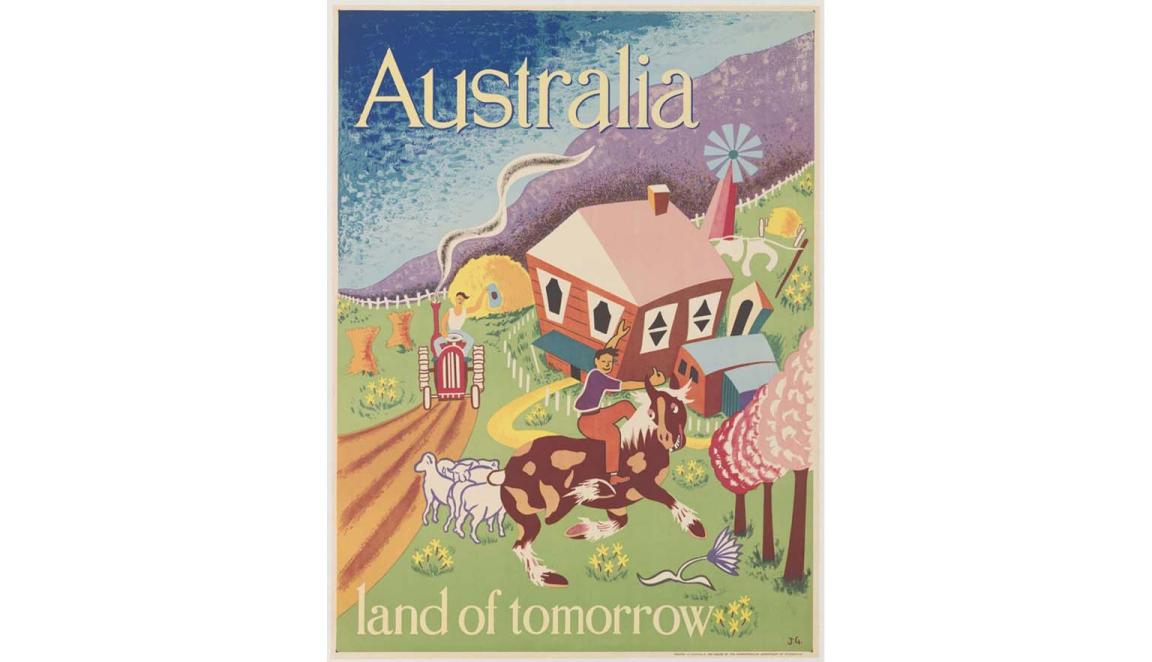

Australia sought to build its own nation in the aftermath of war with bold immigration programs designed to bolster population and, in 1951, a migration agreement was negotiated with the Netherlands. Enticed by passage assistance and promises of wealth, homes, employment and the opportunity to live in an agreeable climate as presented in advertisements such as this immigration poster, many Dutch nationals migrated to Australia to make a new life.

However, Dutch migrants able to pass the strict health, age, security and racial requirements for migration - the White Australia Policy was firmly in place - didn’t have their expectations met.

Arriving with limited funds, they found themselves in the midst of a housing shortage.

The transition to Australian life was difficult with many starting their new lives in migrant camps such as those found at Bonegilla and Bathurst, unaware that they would need to build their own home on arrival. The enticing image of one’s own home furnished with brand new whitegoods was replaced with the grim reality of living in Nissen huts and cleaning old bricks for use as building materials.

Added to this, migrants felt the need to hide their cultural identity in an effort to assimilate and fit in: a distinctive Dutch quality termed Aanpassen.

It took time for the Australian dream to reveal itself.

J. G & Australia. Department of Information, Australia land of tomorrow, 1950, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-137199963

J. G & Australia. Department of Information, Australia land of tomorrow, 1950, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-137199963

Dutch contributions to Australian success

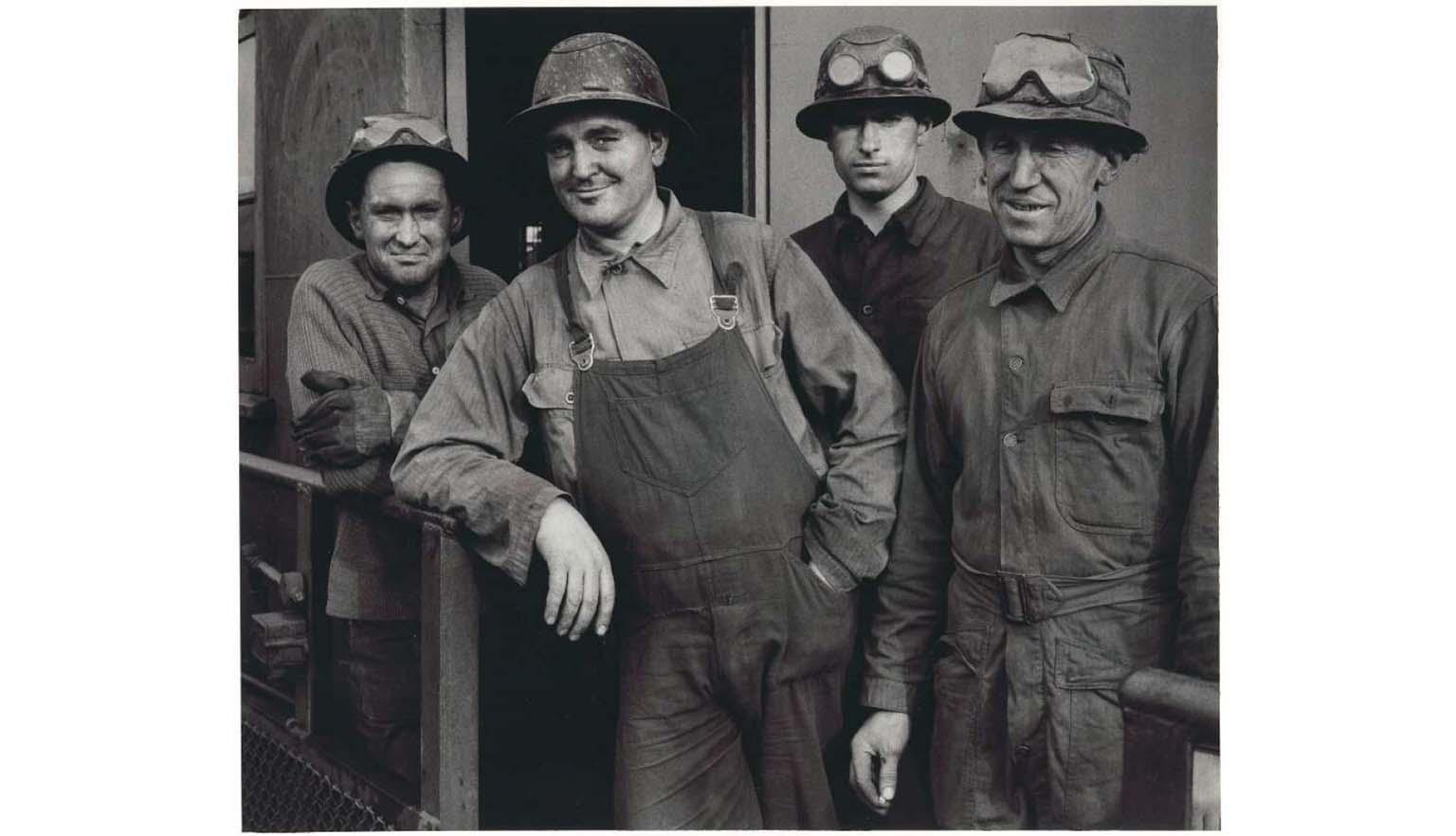

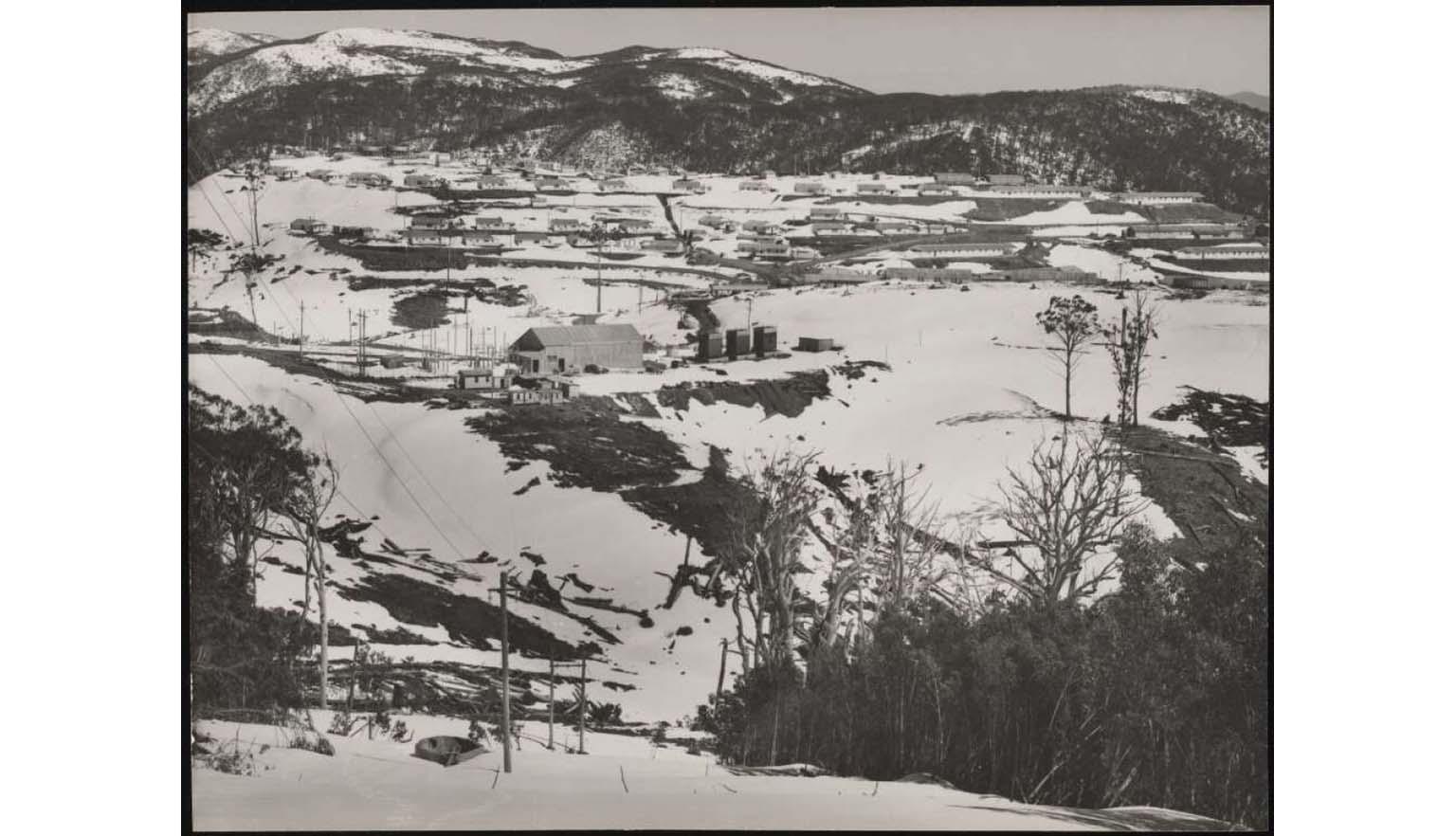

Many migrants found themselves working for the Australian Iron and Steelworks in Wollongong, BHP in Newcastle and the Snowy Mountains Hydroelectric Scheme near Cooma. The Snowy Hydro town of Cabramurra was created with prefabricated houses erected by Dutch tradesmen, when Gerard Dusseldorp formed the company, Civic and Civil. Dusseldorp’s company went on to construct the first part of the Sydney Opera House, among other significant projects.

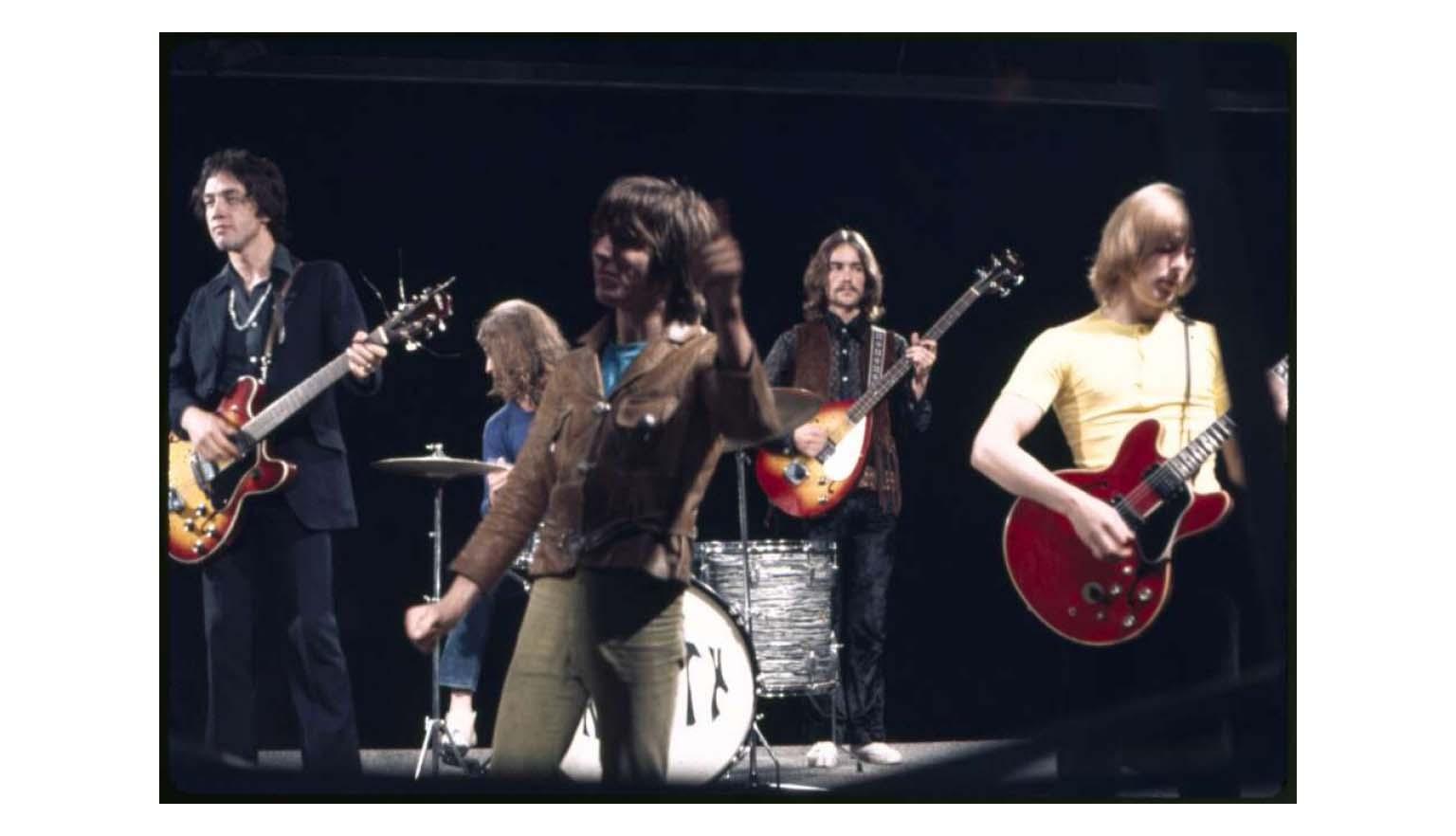

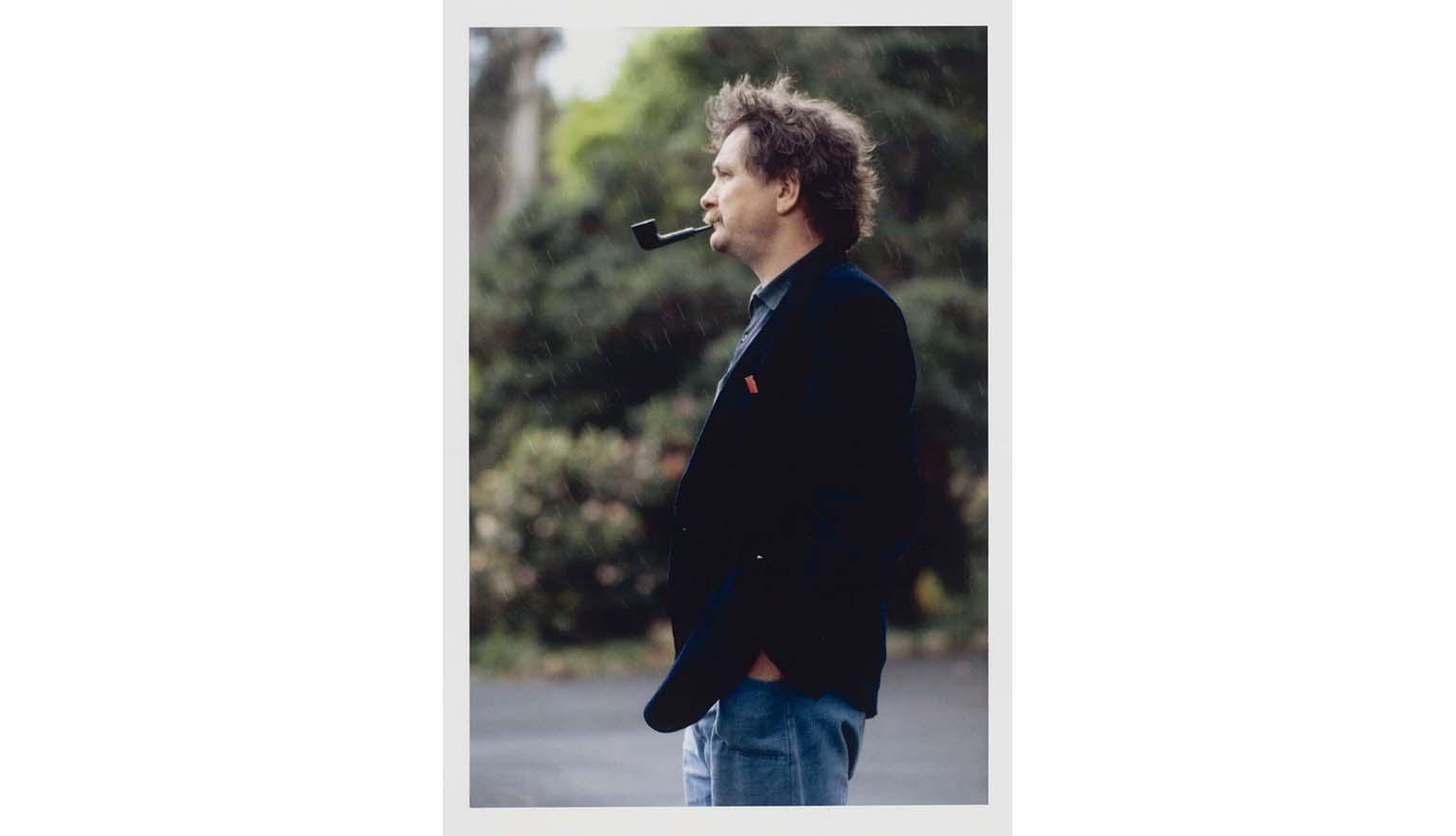

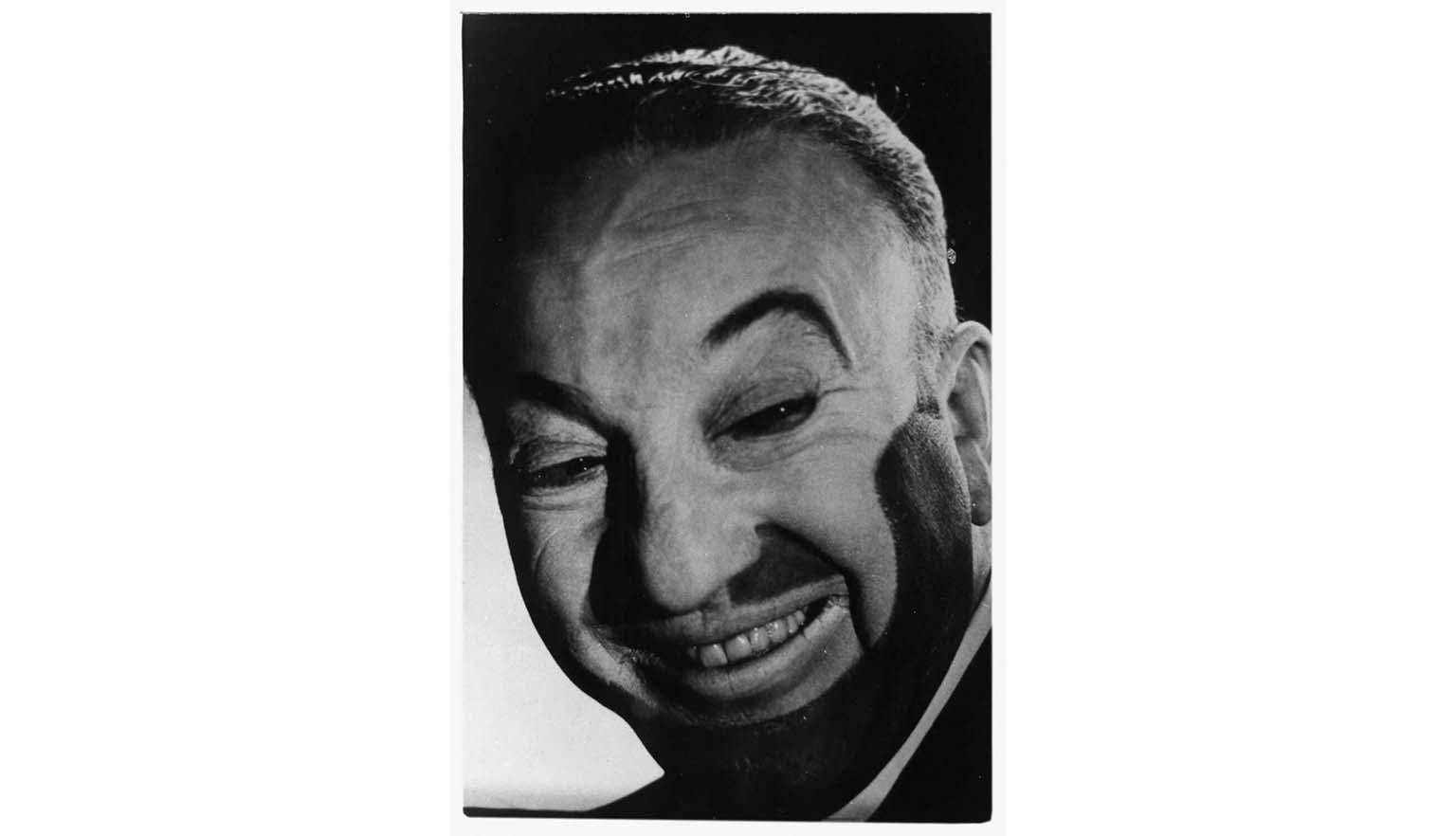

In time, Dutch migrants have found themselves as a vibrant and connected sector of the Australian multicultural community. Weaved into the Australian identity are the success stories of many migrants of Dutch background. In the arts, Rolf de Heer and Paul Cox are award-winning film directors, Harry Vanda was lead singer of the Easy Beats and Roy Rene was one of the most well-known and successful Australian comedians of the twentieth century.

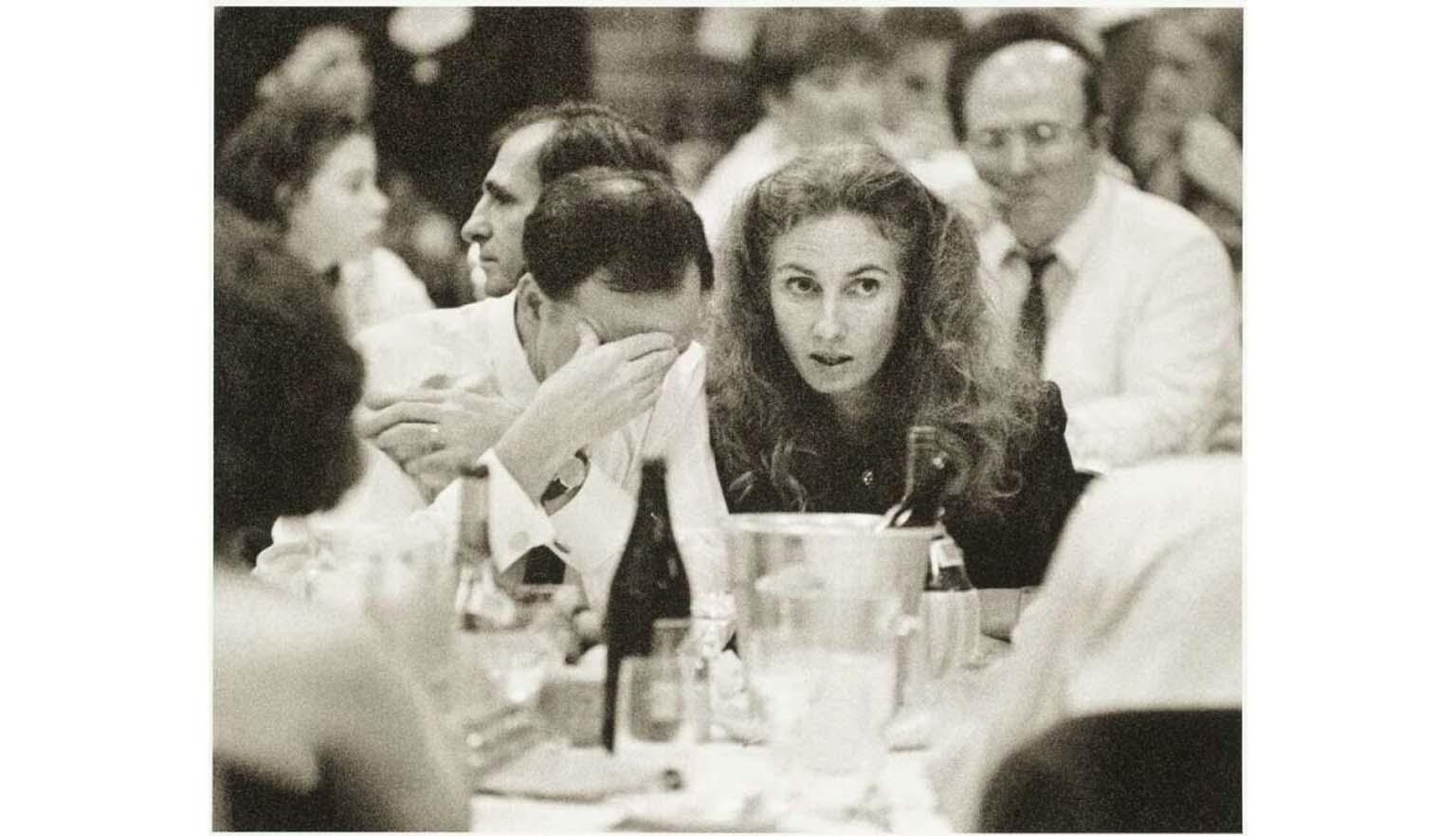

When Paul Keating was prime minister, his then wife, Annita, celebrated her Dutch heritage. Acclaimed academic Nonja Peters now works to showcase these and other success stories, as Australia celebrates 400 years of Dutch connections.

Learning activities

Activity 1: Cracking the code

Introduce students to Morse code using a simple key. Ask them to figure out how to spell ‘Albury’ in Morse. Then, reveal the story of how Albury helped the Uiver during the 1934 London to Melbourne Air Race — a perfect example of community spirit in action.

Activity 2: Mapping the race

Show students the race map with the original 64 entrants.

Students investigate:

- Who made it to the final 20?

- What aircraft did they fly?

- What were the strengths of those planes?

Using Google Maps, students pinpoint the five compulsory stops and the handicap destinations. Each student chooses one aircraft to explore in detail, then join a class discussion on what made certain planes more successful than others.

Activity 3: Game on!

Show students the Dutch commemorative game, inspired by the race.

In groups, students design their own game using:

- The 1934 air race route

- Real competitor profiles

- Challenges like weather or fuel delays

After building their games, they play them in groups and reflect on how different factors shaped the race.

Activity 4: Then and now – shared sorrow

In July Activity 3: 2014, 80 years after the Uiver’s impromptu visit to Albury, the Netherlands and Australia were united in the wake of an air disaster that saw a renewed demonstration of the same mateship and compassion shown in Albury in October 1934. When passenger flight MH 17 was shot down by a missile over Ukraine, Dutch and Australian authorities led an investigation into the causes for the tragedy, united by the desire to hold accountable those responsible.

Have students research and examine the Dutch–Australian relationship in the aftermath of this event, and the combined effort of both countries to ensure accurate and responsible analysis of the disaster. In researching these events, have them answer the following questions:

- What do the Netherlands and Australia have in common with regards to this tragedy?

- What was the nature of the Netherlands–Australia relationship prior to this event? What events had led to this relationship status?

- What has each country contributed to the investigation, in the wake of the MH 17 disaster?

Activity 5: Why migrate?

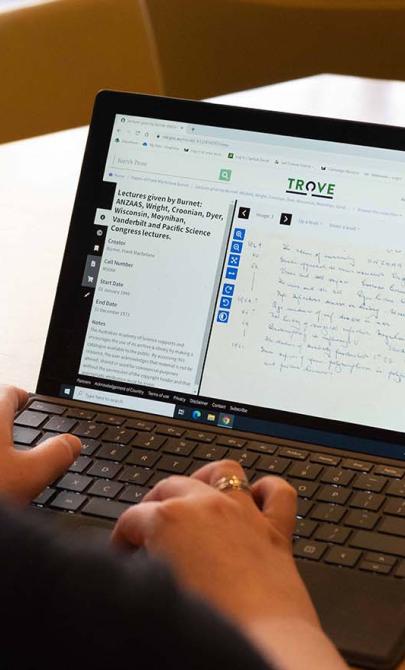

Students conduct a historical inquiry into post-WWII Dutch migration to Australia. Their response could be an essay, mini-exhibition or report. Using Trove and other sources, they explore:

- What pushed/pulled Dutch migrants to Australia

- Government agreements and migration rules

- Where people were housed and what jobs they took

- The 1952 Bonegilla riot

Activity 6: A letter from Bonegilla

Watch the short 3Hands Studios animation about life at Bonegilla.

Although this film does not feature Dutch migrants, it offers two perspectives of ‘displaced person’ migrants (those received from 1947) on their experiences at Bonegilla, which would have been similar for Dutch people in that same centre as ‘assisted migrants’ (those received from 1951).

Students should use this as inspiration to write a letter from the perspective of a Dutch migrant, either a child or an adult, living at Bonegilla. They should include:

- What life was like before Australia

- Their hopes, disappointments and ambitions

- How they were adjusting to life in a new country

Activity 7: Dutch footprints

Having left the government provided accommodation centres, many migrants assimilated quickly into Australian life, starting their own businesses or contributing to established industries and companies. They had children of their own, starting a new generation of Australians with Dutch ancestry. Share with students, stories of the notable Dutch migrants featured above, giving a brief account of their life in Australia.

Students should research one or more Dutch migrants (or the migrant heritage of a first generation Australian with Dutch ancestry) and the contribution they have made to Australian life. This person need not be famous, and students should be encouraged to discover people of Dutch origin in their own community, or those less well known. You may consider approaching a local Dutch community group, and have students write interview questions and make contact, if appropriate. They should present their findings in a suitable format for sharing with the rest of the class, which might include a video presentation, should students be able to interview people in person. In forming a list of interview questions, or, in structuring their research, they should consider:

- The age that the migrant was on arrival

- Whether they spent time in a migrant accommodation centre

- The life they left behind

- Their prior skill set

- Their chosen profession

- Their initial impression of life in Australia

- How they went about finding or creating work for themselves

- Their chosen location for settlement and why

- Whether they celebrate their Dutch heritage

- The contribution they have made in Australia.

Activity 8: Welcome kit

Have students create a “Welcome to Australia” kit for modern Dutch migrants.

Include:

- Suggested places to settle

- Events and community groups

- Dutch-Australian newspapers and websites

They can present their kit as a brochure, poster, or digital guide.

Acknowledgement

This resource has been generously supported by the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Australia, to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the arrival of Dirk Hartog on the West Australian coast in 1616.