Dutch–Australian connections in World War II

The Fall of the Netherlands East Indies

The Dutch-governed islands to the north of Australia were an essential physical defence between Australia and the looming threat of Japan. The Netherlands and Australia formed a vital alliance, combining forces on land, sea and in the air, in the defence of Australia and the region, as Japan established its foothold in the Pacific.

Despite this alliance, the Netherlands East Indies fell to the Japanese in 1942, giving Japan much needed resources and a valuable naval and air base. Dutch colonials and military staff were put into prisoner-of-war camps, as evacuations hurriedly took place. As the Japanese assumed power, the Netherlands East Indies Government reached an agreement with Australia, and became the only foreign government-in-exile on Australian soil, located for the most part, at Camp Colombia in Queensland.

Dutch Evacuations to Australia

The Netherlands and Australia forged a considerable friendship. Many Dutch in the region fled to Broome on the north coast of Western Australia. Dutch warships were repaired or stationed in Fremantle. The Netherlands donated hospital ships to Australia, such as the Oranje, pictured here. Several joint units were established, such as the No 18 and No 120 RAAF squadrons.

The Bombing of Broome

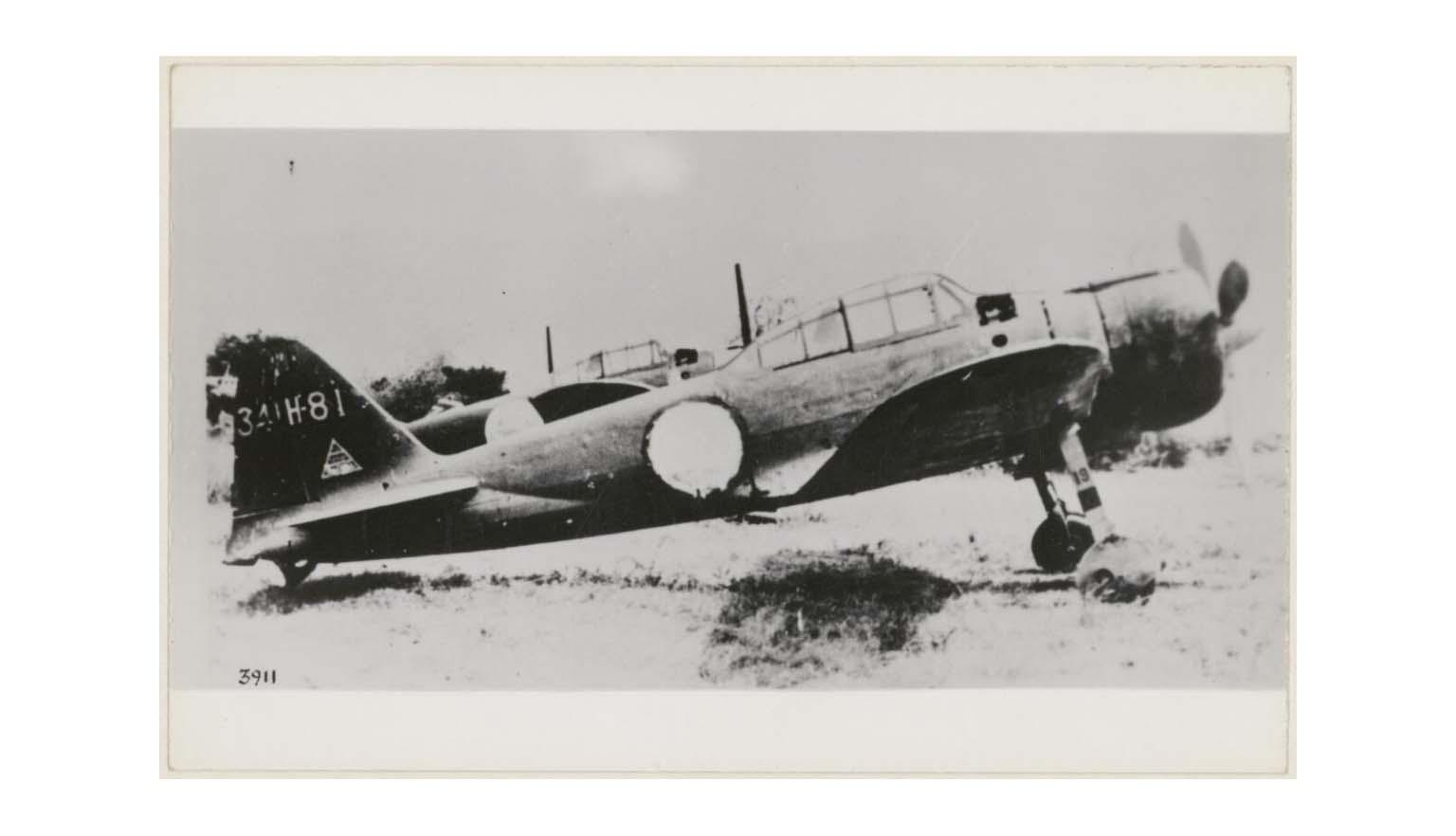

The bombing of Broome in 1942 brought many Dutch casualties. Having just fled Java, Dutch women and children were waiting in crammed flying boats in Roebuck Bay to refuel before heading to other destinations. When Japanese Zero fighter planes attacked, 76 Dutch nationals were killed. Many others were injured.

Broome was unprepared for the attack, but one man was able to return fire. At Broome’s airbase, Dutch pilot Gus Winckel removed a machine gun from his plane and shot down one of the Japanese planes, sustaining burns to his arm. He later received a medal for his efforts.

As the war concluded, Dutch colonial rule in the region was fading and, after three years of occupation by the Japanese, Indonesia resurrected itself as an independent country, bringing to a close the Dutch hegemony that had lasted nearly 350 years.

The case of the Carnot Bay missing diamonds

On 3 March 1942, PK-AFV Pelikaan, a Dutch airliner piloted by Russian WW1 flying ace Captain Smirnoff, was evacuating military personnel and civilian passengers from Bandung in the Netherlands East Indies. Just before its early morning departure, Captain Smirnoff was approached by the airport station manager with a package, wax-sealed by the Dutch Javasche Bank, and instructed to hand it to a representative of the Commonwealth Bank once he reached Australia.

The Japanese Zeros returning to Timor, having just completed their air raid on Broome, were surprised to find the Dutch airliner below them in the sky. They shot down the plane, which crash-landed in the surf at Carnot Bay, about 80 kilometres north of Broome.

Having survived the crash, four passengers were killed, including a mother and her eighteen-month-old baby, when the Japanese returned to strafe the plane. The next day, the Japanese returned to bomb the plane and the survivors, however no further lives were lost. After six days on the beach, the Dutch crew and remaining passengers were rescued by a party from Beagle Bay.

But what of the package handed to Captain Smirnoff before departure? The parcel contained £300,000 worth of diamonds, the equivalent of around $20 million in today’s money. While Smirnoff claims he never knew what the package contained and that it had been lost in the surf, others claim he knew of the package contents and intended to retrieve them. Jack Palmer, a Broome local who visited the crash site days after the rescue, later handed in a number of diamonds, but they were only a small percentage of the entire package. He said that he had found the bag at the crash site, but that most of the diamonds had fallen out, lost to the sand.

Palmer and two colleagues, Frank Robinson and James Mulgrue, were tried and acquitted of diamond theft. Others claim the diamonds were circulated among the local Indigenous children and yet other stories suggest they were found in the fork of a tree, in a fireplace and in the possession of a Chinese trader.

No one has ever been convicted of the diamond theft, and today the whereabouts of the diamonds are still unknown.

Learning activities

Activity 1: Japanese Air Raids on Australia

Research the approximately 100 Japanese air raids on Australia during WWII, focusing on:

- Main targets and their strategic importance

- Types of Japanese aircraft used

- Factors contributing to raid success

- Consequences for Australia’s war effort

- Impact on Australia’s WWII participation

Activity 2: Henk Hasselo’s Oral History

Listen to Henk Hasselo’s Oral History (Session 2, 01:00:09–01:10:00) about the Broome bombing. Answer:

- How did Henk identify the Japanese Zero?

- Where was he during the attack?

- What actions did he take?

- What injury did he sustain?

- Who was in the water, and how did he respond?

- What were the Japanese targeting?

To find additional primary sources, use:

- The library catalogue

- Australian War Memorial

- National Archives

Activity 3: Gus Winckel and the Broome Bombing

Using Trove, locate newspaper articles from March 1942 about the Broome bombing and Gus Winckel’s actions. Reflect on:

- Why is some information repeated across articles?

- What is the likely source of the original information?

- How does war affect published information?

- How do primary sources (e.g., Henk’s interview) compare to secondary sources (e.g., newspapers) in accuracy?

Write a modern-day letter from a 1942 eyewitness (for example, Henk Hasselo, Gus Winckel) to their grandchild, recounting the bombing and reflecting on its impact on their life and Australia.

Acknowledgement

This resource has been generously supported by the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Australia, to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the arrival of Dirk Hartog on the West Australian coast in 1616.