Cowra

Cowra Prisoner of War camp

Opened in 1941, the Cowra camp was established to house the growing number of Prisoners of War (POWs) from the Mediterranean theatre, primarily Italian and German troops.

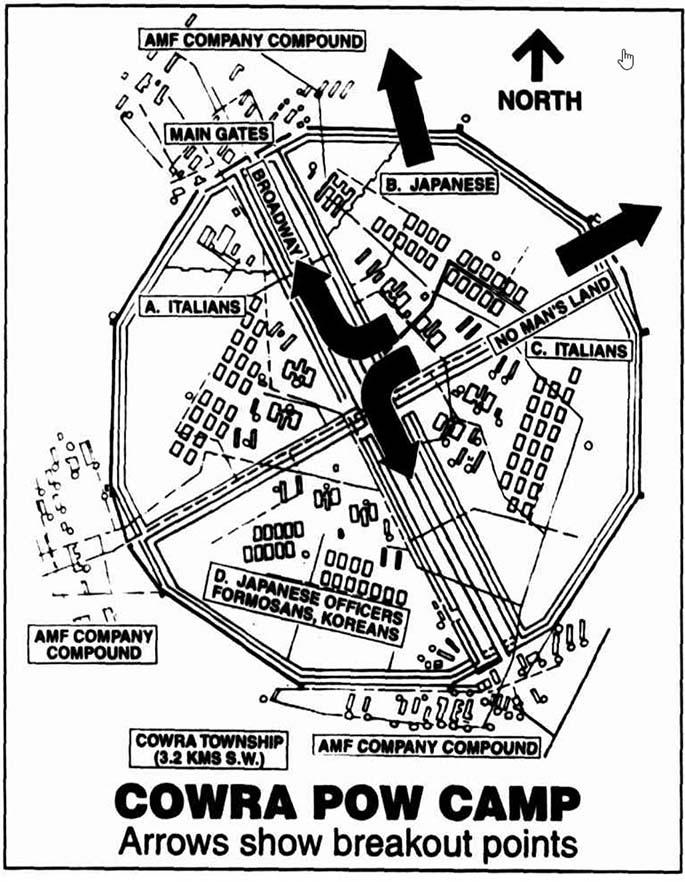

The camp layout followed a standard design:

- A perimeter fence enclosed approximately 28 hectares

- Two intersecting roads divided the area into four compounds

- One road, known as Broadway, was wide enough for vehicles

- Each compound was separated by wire and barbed fences

Although primarily a POW camp, Cowra also housed civilian internees, including:

- Local Italian Australians

- Nearly 500 Indonesians

Cowra is best known as the site of the largest prison breakout of World War II—and the bloodiest.

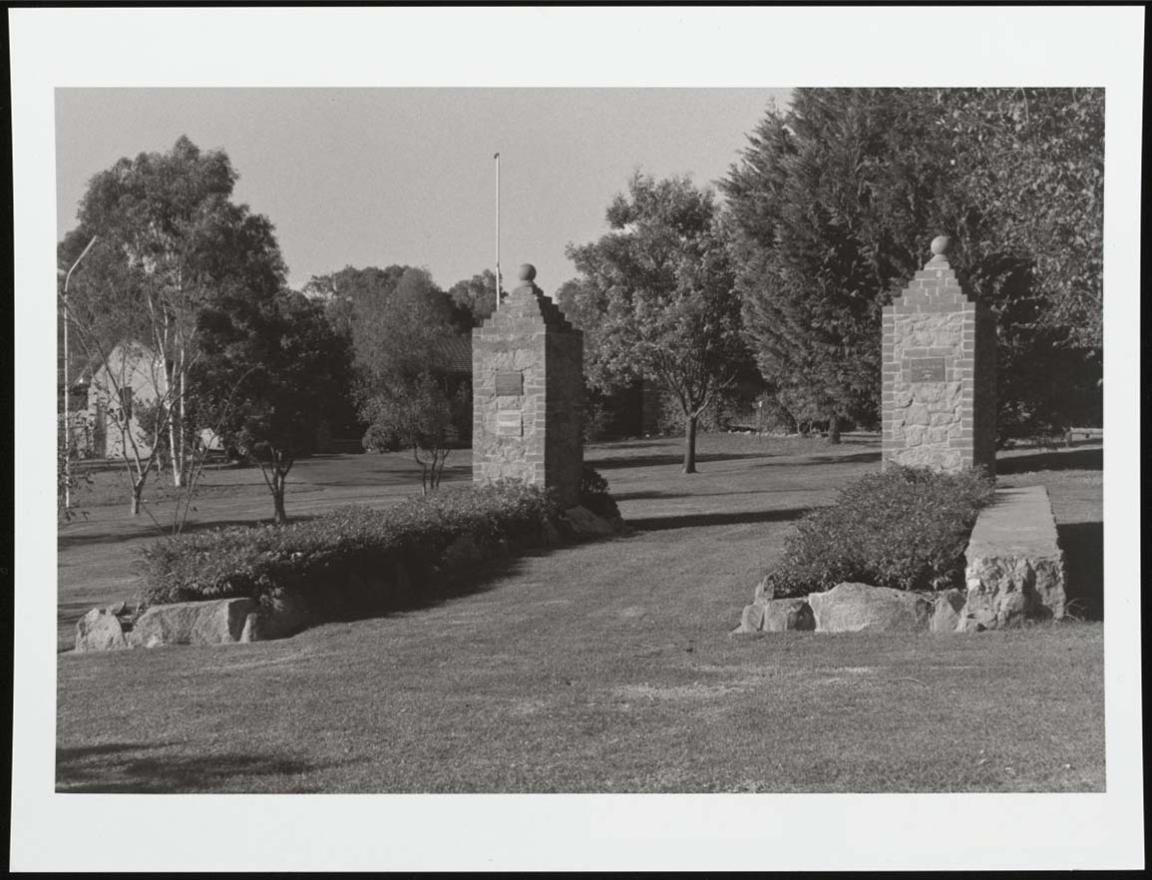

Brendon Kelson, Garrison Gates Memorial (former entrance to POW camp), Binni Creek Road, Cowra, 1996, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-143115748

Brendon Kelson, Garrison Gates Memorial (former entrance to POW camp), Binni Creek Road, Cowra, 1996, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-143115748

Unrest

In August 1944, a dramatic and tragic event unfolded at the Cowra POW camp in NSW. Japanese prisoners, driven by cultural beliefs that saw capture as a deep dishonour, launched a mass breakout that would leave a lasting mark on both survivors and their captors.

Unlike German or Italian POWs, many Japanese soldiers viewed surrender as a fate worse than death. Suicide was often preferred, and those who were captured typically refused to give their real names or contact their families—believing it more honourable for loved ones to think they had died in battle.

By mid-1944, Cowra’s Japanese compounds were overcrowded, housing not only military personnel but also around 500 merchant seamen. As Japan’s position in the war weakened, the prisoners faced the prospect of returning home in disgrace. For some, escape—even at the cost of their lives—offered a chance to reclaim lost honour.

When Australian authorities announced plans to transfer 700 prisoners to another camp in Hay, tensions boiled over. The men had formed a close-knit community, and the threat of separation sparked unrest. In B Compound, talk of rebellion turned into action.

Despite knowing the odds were against them—Cowra was remote, and escape routes were limited—the prisoners voted to act. On the night of 5 August, they launched a coordinated assault: some targeted machine gun posts, others aimed to breach the perimeter, and a third group planned to storm the guards’ quarters.

The breakout was ultimately unsuccessful, but its impact was profound. It revealed the deep cultural divide between captors and captives, and the lengths to which men would go to preserve their sense of honour.

The breakout

Just before 2 am on 5 August 1944, a bugle call signalled the start of the Cowra breakout. Japanese prisoners surged into Broadway, the main road through the camp, catching the guards by surprise. A key guard tower, equipped with a Bren gun, was unmanned.

The prisoners forced open the gate. At the same time, fires were lit in the Japanese huts. These fires consumed the buildings—and the bodies of around 20 prisoners who had taken their own lives rather than face the shame of capture.

FEATURES The night the sky was glowing red (1994, July 9). The Canberra Times (ACT : 1926 - 1995), p. 42. nla.gov.au/nla.news-article118189979

FEATURES The night the sky was glowing red (1994, July 9). The Canberra Times (ACT : 1926 - 1995), p. 42. nla.gov.au/nla.news-article118189979

Resistance and sacrifice

Two Australian soldiers, Ralph Jones and Ben Hardy, played a critical role in halting the breakout. Both were posthumously awarded the George Cross.

They realised that whoever reached the unmanned machine gun first would determine the outcome. The two men raced to the gun, ahead of more than 200 Japanese POWs armed with makeshift weapons.

Jones and Hardy opened fire. Some prisoners were killed, others took their own lives, but many breached the final fence and attacked the gun. The two Australians continued firing until they were overpowered and killed. The Japanese were unable to operate the gun and fled.

Chaos and casualties

Fires raged through the camp. Australian guards took positions at both ends of Broadway and fired into B Compound. Some prisoners reached D Compound, where Japanese officers were held.

Ichiro Takata, a survivor, later described the moment:

As I was running I was praying for a bullet … I could see my comrades going down like dominoes … I tried to take my own life with a knife … I shut my eyes quietly … I was becoming satisfied that I would finally die … I felt proud again to be a soldier of the Japanese Army.

By 6:20 am, a ceasefire was called. Around 500 prisoners had been rounded up, but 300 had escaped into the surrounding countryside.

Although there were fears that the escapees posed a threat to civilians, Japanese military code did not permit violence against non-combatants. However, Australian soldiers were considered legitimate targets.

Some escapees chose suicide over recapture. One, Shoichi Yamamoto, attempted to shoot himself with an unloaded rifle. He was recaptured but later died in hospital.

Aftermath

The first round-up began before dawn. Many prisoners surrendered to patrols made up of:

- Australian soldiers

- Police officers

- Civilians

One Australian soldier, Harry Doncaster, was killed during the search. A member of the Volunteer Defence Corps also died from accidental gunshot wounds.

In total:

- 234 Japanese prisoners died

- 334 were recaptured, including 25 who had died after escaping

- No one successfully escaped

Cowra today

Today, Cowra is a place of remembrance and reconciliation.

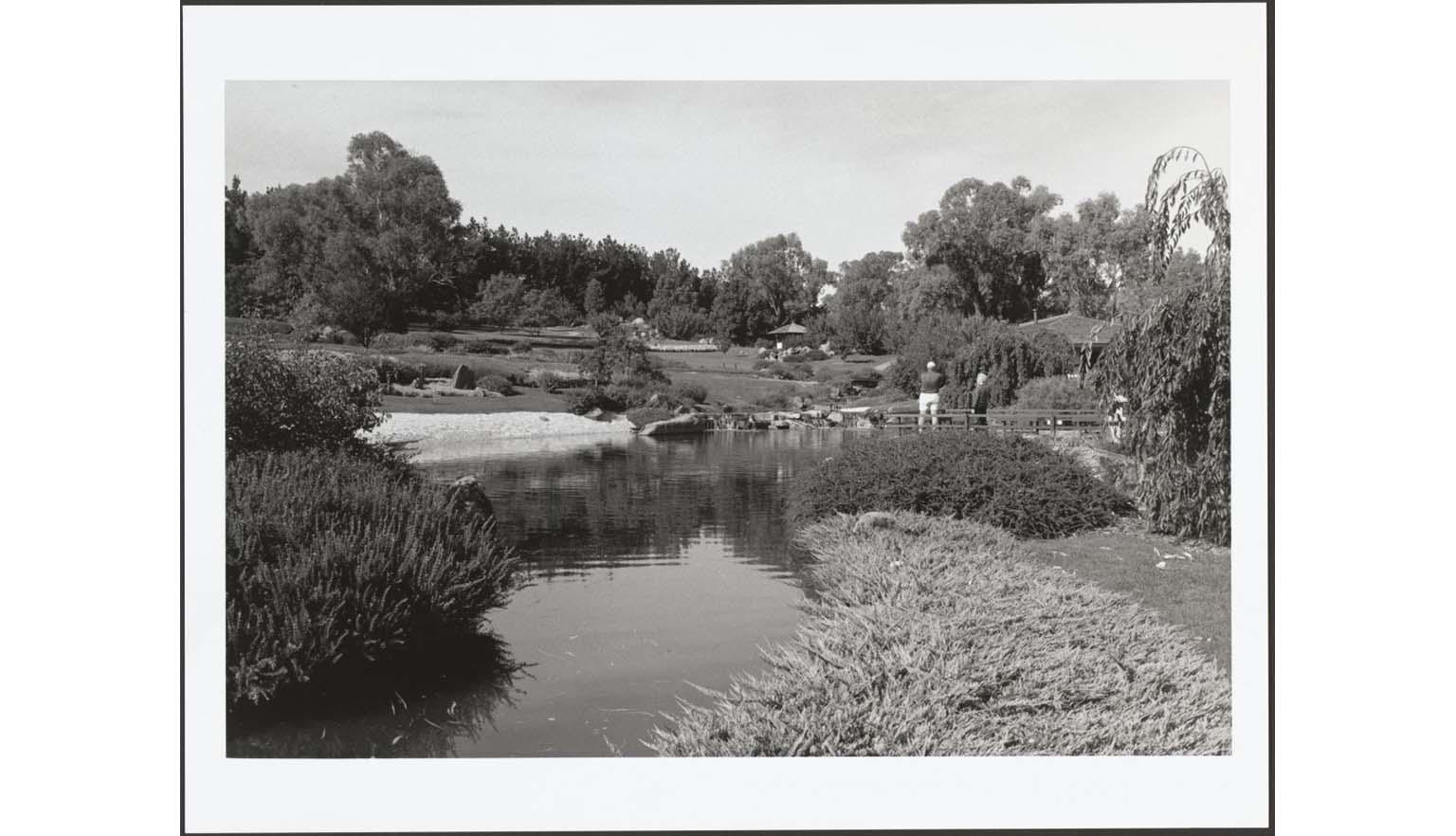

The town is home to:

- The Japanese Garden and Cultural Centre, which hosts the annual Sakura Matsuri (Cherry Blossom Festival)

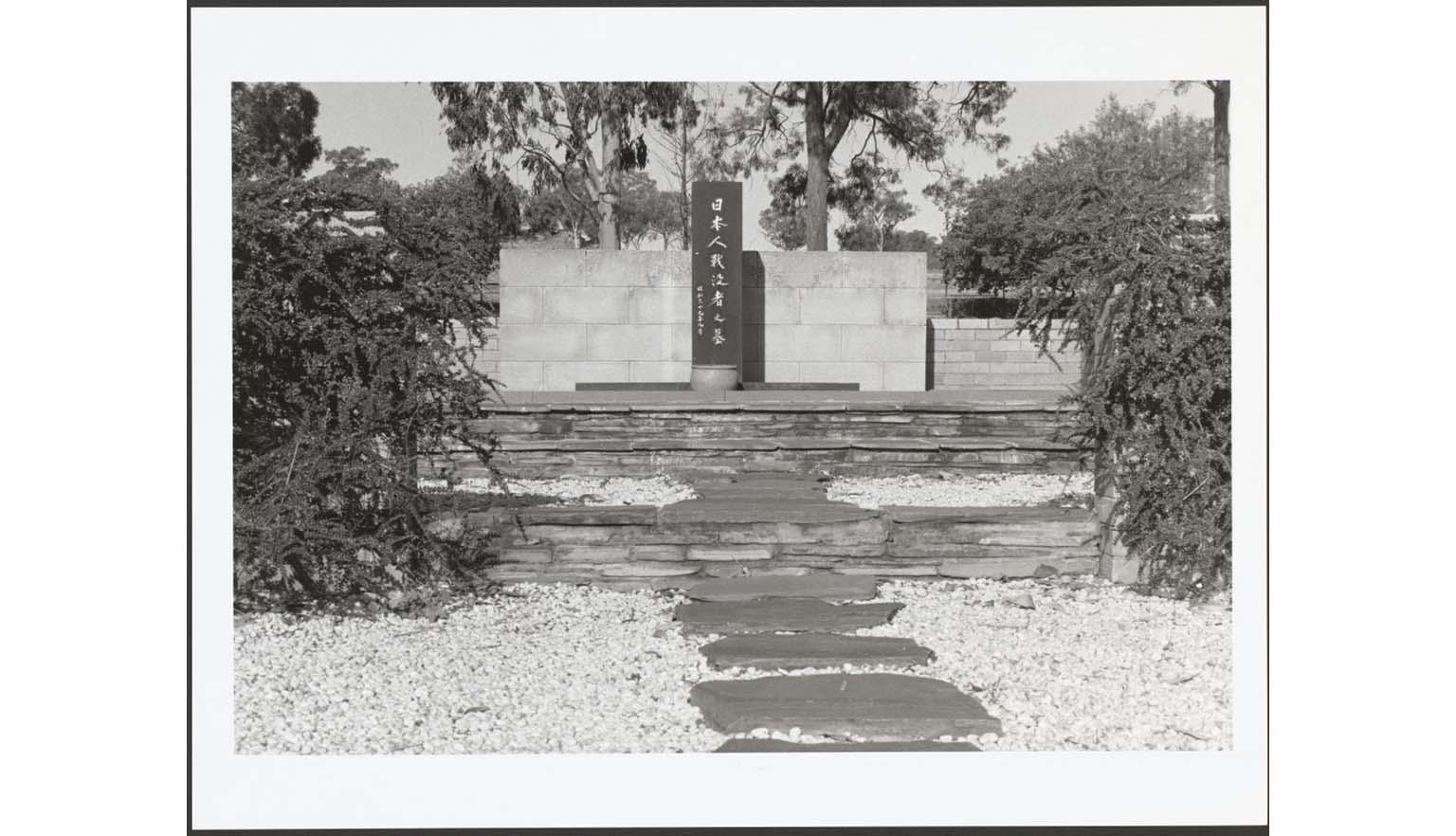

- The Japanese War Cemetery, the only one of its kind in Australia

- The Australian War Cemetery, where the four Australians killed in the breakout are buried

- A memorial plaque honouring the Australian soldiers who died during the breakout

Learning activities

These activities explore the internment of prisoners of war in Australia during World War II, focusing on the Cowra camp, its local impact, and the legacy of remembrance and reconciliation.

Activity 1: Why Cowra?

Cowra, in central western New South Wales, was chosen as the site of a large internment camp during World War II.

- Begin by locating Cowra on a map. It is approximately 300 kilometres inland from Sydney.

- Ask students to consider:

- Why might this remote inland location have been chosen for a camp?

- What strategic or security reasons might have influenced this decision?

- Using Trove, or other online map sources, find and examine a map of internment camps across Australia during World War II.

- As a class, discuss:

- Are there patterns in where these camps were located?

- What do the locations suggest about government priorities and public concerns?

Activity 2: Life inside and outside the camp

Internment could be a source of uncertainty and fear—for both prisoners and local residents.

- Ask students to reflect on how prisoners might have felt when told they were being transported to a new camp:

- What might cause them stress or anxiety?

- Would they have had information about where they were going or why?

- Invite students to take the perspective of a Cowra resident in 1941–1944:

- How would you feel knowing several thousand ‘enemies’ were being held near your town?

- What concerns might residents have had?

- What impacts—economic, social or emotional—might the camp have had on Cowra?

- Use Trove Newspapers to locate articles about the Cowra breakout and its aftermath.

- Ask students to summarise how the event was reported in the media.

- Discuss how tone, headlines and language reflect public attitudes at the time.

Activity 3: Remembering Cowra and reconciliation

Cowra is home to both the Australian War Cemetery and the Japanese War Cemetery—a rare example of shared remembrance between former enemies.

- Introduce students to the existence of the Japanese War Cemetery in Cowra.

- Ask them to explore and discuss:

- What does the creation and care of the Japanese cemetery suggest about changing attitudes after the war?

- Why is it significant that these graves are looked after on Australian soil, near those of Australian soldiers?

- Extend the activity:

- Are there other known examples of former enemies caring for the graves of those they once fought against?

- What might this say about forgiveness, respect and the long-term impact of war?