Dunera

Enemy aliens

In the years leading up to World War II, the Nazi regime’s antisemitic policies became increasingly violent. Many German Jews fled to Britain and other countries to escape persecution. However, when war was declared between Germany and the United Kingdom, these refugees were reclassified as ‘enemy aliens’.

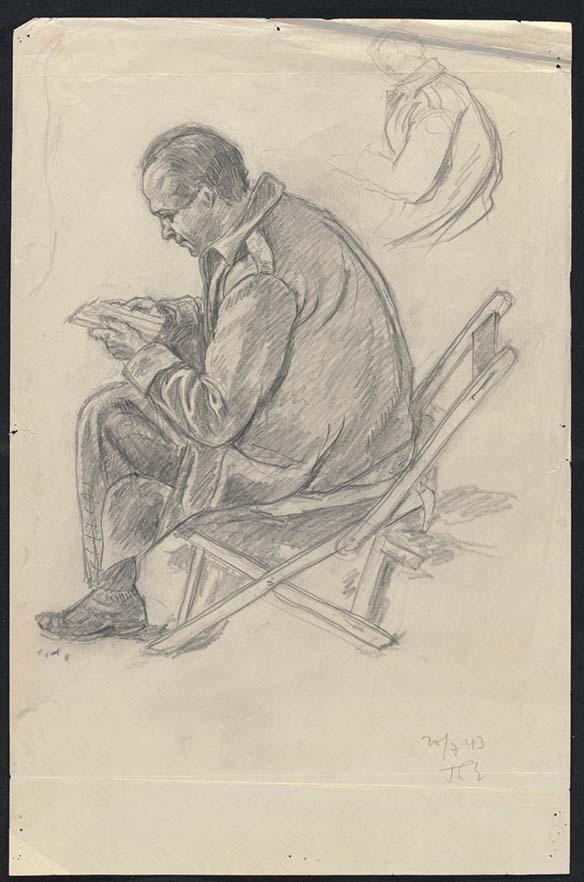

Theodor Engel, Study of a Dunera boy in a deck chair, 20 July 1943, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-153000808

Theodor Engel, Study of a Dunera boy in a deck chair, 20 July 1943, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-153000808

Initially, this reclassification had little effect, as it was understood that these individuals were fleeing Nazi oppression. But after Germany’s victories in France and the Low Countries, panic set in. The British Government ordered the mass arrest of enemy aliens, regardless of their religion, politics or personal history.

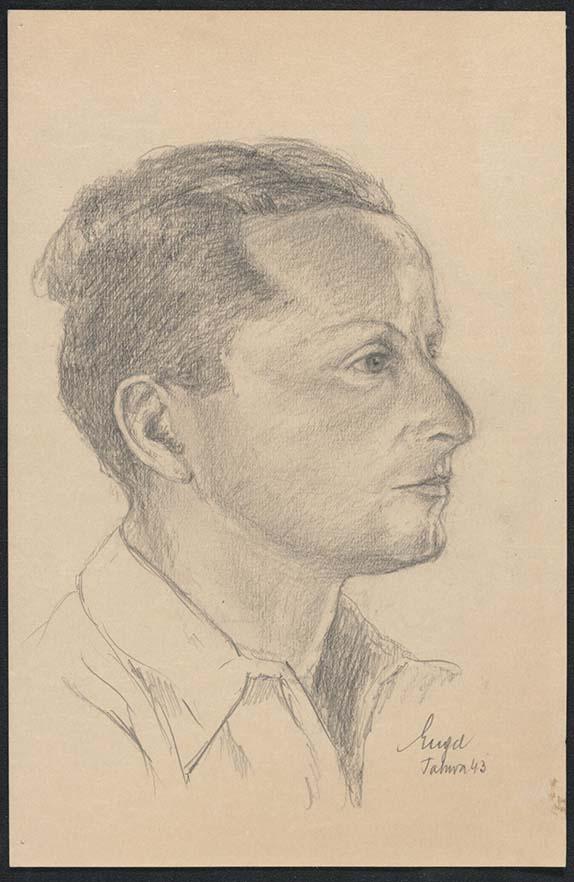

Theodor Engel, Study of a Dunera boy at Tatura, Victoria, 1943, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-152997802

Theodor Engel, Study of a Dunera boy at Tatura, Victoria, 1943, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-152997802

HMT Dunera

To reduce the number of internees in Britain, the government arranged for some to be transported to dominions such as Australia. Passenger ships were repurposed for this task, including the HMT Dunera.

The Dunera carried 2,542 people, including:

- 2,036 anti-Nazi refugees, most of whom were Jewish

- 200 Italian prisoners of war

- 251 German prisoners of war

- A small number of Nazi sympathisers

Tensions were high on board. Fights broke out, and the 300 British guards assigned to the voyage were often violent toward the passengers.

The ship departed Liverpool on 10 July 1940. Originally a luxury liner, the Dunera was dangerously overcrowded. Hygiene supplies were scarce, disease spread rapidly, and the threat of German U-boat attacks loomed constantly.

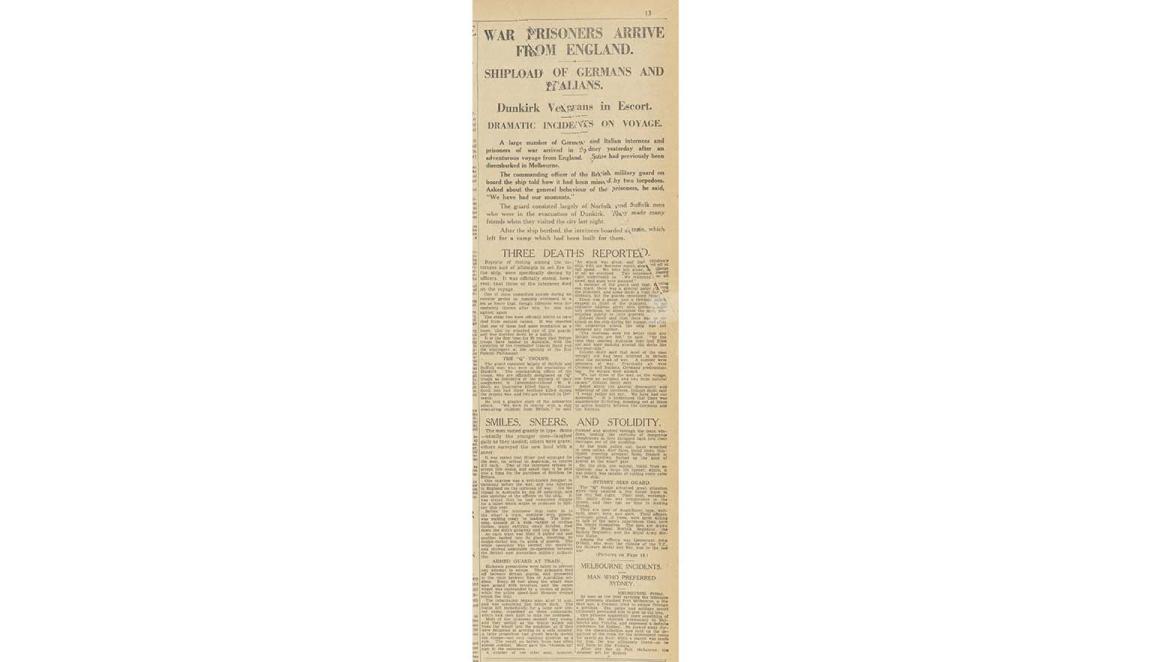

WAR PRISONERS ARRIVE FROM ENGLAND. SHIPLOAD OF GERMANS AND ITALIANS, The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 13, 7 September 1940, nla.gov.au/nla.news-article27947256

WAR PRISONERS ARRIVE FROM ENGLAND. SHIPLOAD OF GERMANS AND ITALIANS, The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 13, 7 September 1940, nla.gov.au/nla.news-article27947256

An Australian officer who boarded the ship in Fremantle was shocked:

All these internees … were dumped on the ship and told to get out to Australia, without any thought of documents or anything else. The whole show is terrible, if you could see these Huns and Dagos behind the wire after 2 months at sea, with rough weather all the way, you would wonder how on earth they survived it.

Arrival in Australia

When the Dunera docked in Sydney, the passengers were transferred to a train bound for Hay, New South Wales. For many, this marked the first moment of kindness since their ordeal began.

Eric Eckstein, one of the internees, recalled:

Once we were on the train everyone was friendly, especially the guards... George thought it was ‘bloody rotten’ to trick people like that... George was the first person to appear genuinely interested in what had happened to us... All he could do was shake his head and say: ‘Well I never, the rotten bastards’.

The internees had little idea where they were going. Walter Kaufmann, one of the youngest aboard, described the journey:

We travel into the darkness … At dawn the train halts. In black on the grey station wall is emblazoned the word HAY … Under a cloudless sky and scorching sun … we march from the station … toward the watch-towers.

The Italians aboard the Dunera

The Italian internees aboard the Dunera disembarked earlier than the others, arriving in Melbourne before being transported to internment camps in Victoria. Like many of the Germans, these Italians were anti-fascists who had lived in Britain for years before being deported.

Marco Gazzi, one of the Italian passengers, recalled a surprising moment of kindness:

The sergeant came into our compartment and spoke to us and we all answered in English, and he said to us, ‘Ohrrr you speak better English than we do’. We were all Italian, but we all spoke with a different accent, Welsh, Scottish and London, and he said to us, ‘Do you all smoke?’ and he went off and bought a packet of Woodbine cigarettes, and gave us all one. I said, ‘You can give mine to one of the others - I don’t smoke’, and off he went and bought me a two ounce [60 gram] block of Nestlé’s chocolate. And my thought was: ‘If an Army Sergeant can do that for me, it must be a wonderful country.’

However, not all experiences were positive. Vittorio Tolaini, another Italian internee, was sent to Loveday internment camp in South Australia. He described his treatment there:

Our treatment in Camp 10 was very harsh. Bashed with the butts of rifles we were pushed into a large hall and forced to strip naked whilst the guards thoroughly examined each piece of clothing. Some of us were coerced to submit to an extremely degrading investigation. We were forced to bend forward while medical staff closely handled and explored the most intimate parts of our bodies to ensure that we didn’t have anything hidden there. It was a terrible experience.

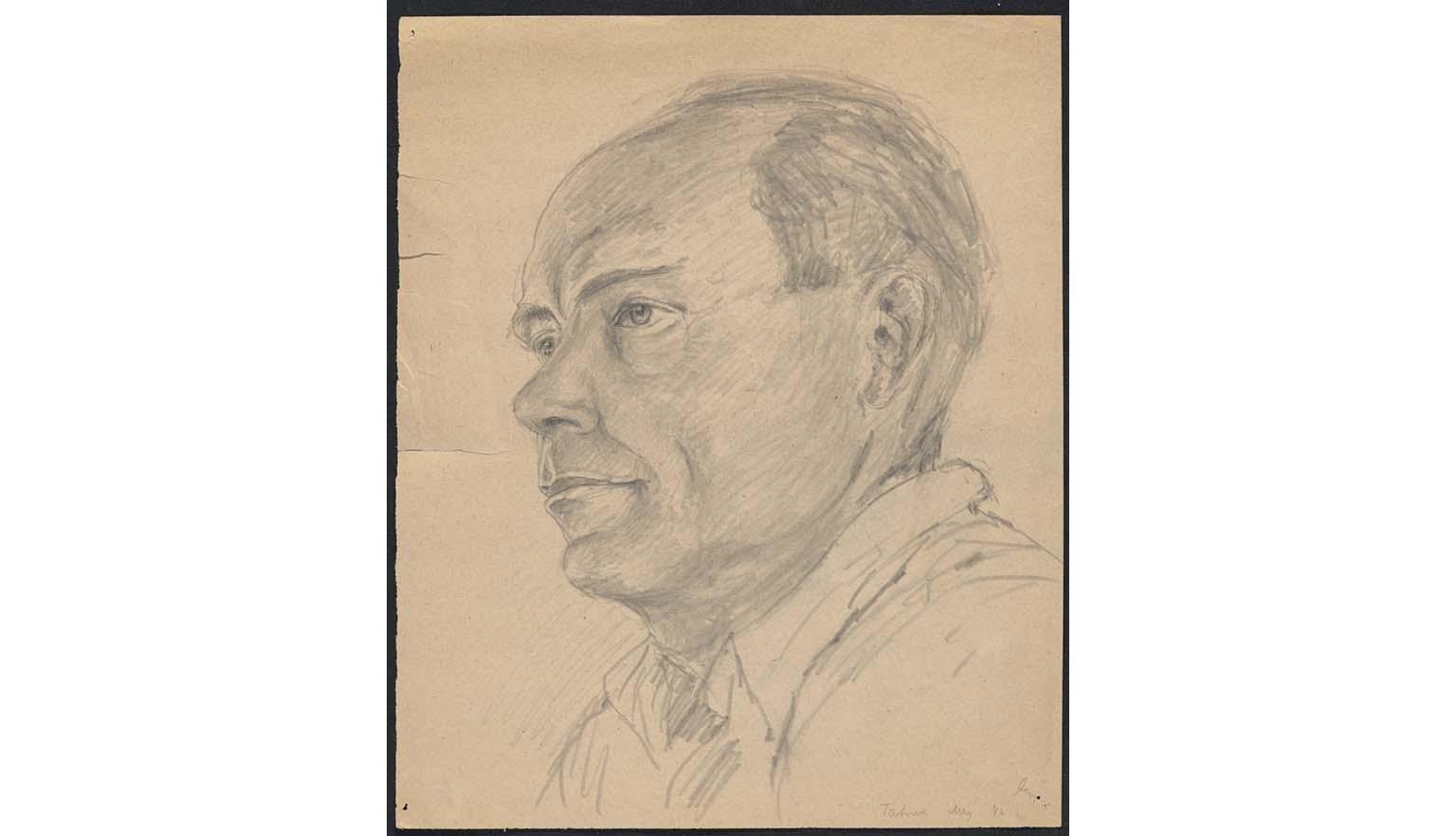

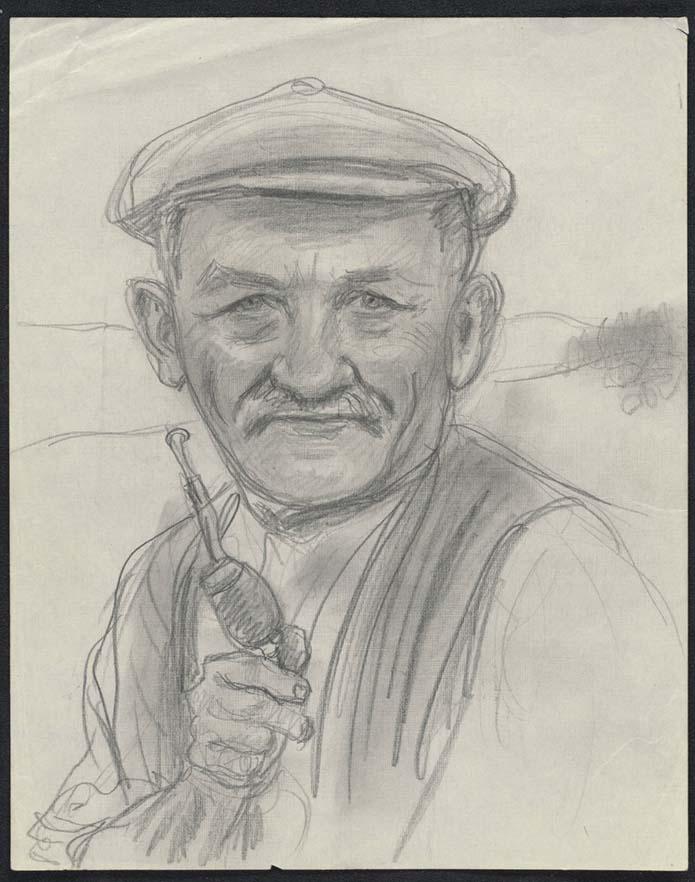

Theodor Engel, Study of a Dunera boy holding a pipe, 1942, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-152997209

Theodor Engel, Study of a Dunera boy holding a pipe, 1942, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-152997209

Aliens distinguished

On 30 July 1941, the Australian Government announced it would accept 300 Japanese internees if required. Eventually, 3,160 Japanese people were transported to Australia from Allied-controlled territories, including:

- New Zealand

- New Caledonia

- The New Hebrides (now Vanuatu)

- The Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia)

At the start of the war, 1,103 Japanese residents in Australia were also interned. By November 1946, when the last internees were released, 3,268 Japanese people remained in Australian camps.

In February 1942, the government introduced new classifications under the National Security Regulations, distinguishing between:

- Allied nationals

- Enemy aliens

- Neutral aliens

- Refugee aliens

This change led to the release of many Dunera Boys, who were reclassified as refugee aliens. Many of them volunteered for service in the Australian armed forces. Although they were not permitted to serve overseas, they joined the 8th Australian Employment Company, working alongside more than 500 other Jewish refugees to support the war effort.

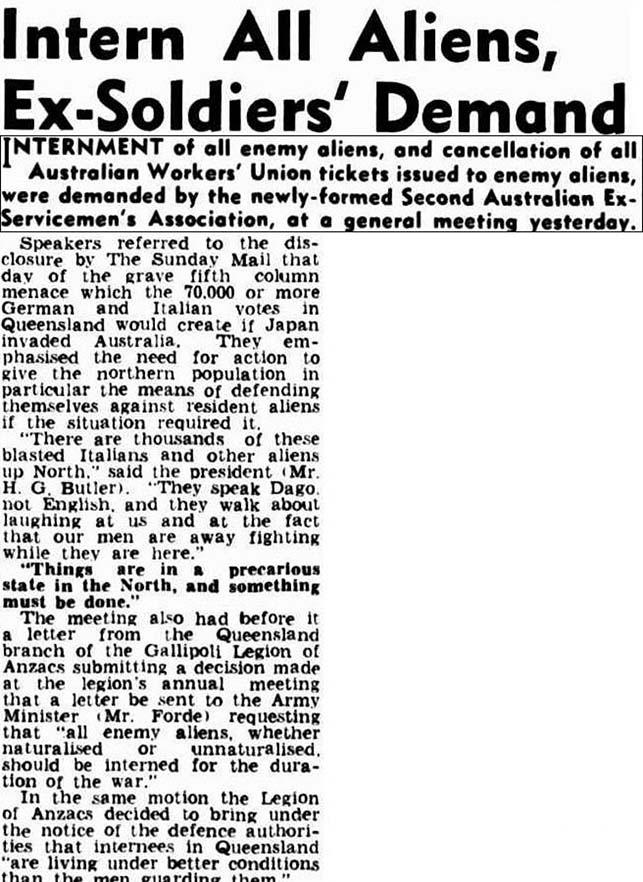

Despite their contributions, some Australians opposed the release of internees. Ex-soldiers and members of the public called for the internment of all aliens, regardless of their status.

Intern All Aliens, Ex-Soldiers' Demand (1942, February 2). The Courier-Mail (Brisbane, Qld. : 1933 - 1954), p. 3. nla.gov.au/nla.news-article50137810

Intern All Aliens, Ex-Soldiers' Demand (1942, February 2). The Courier-Mail (Brisbane, Qld. : 1933 - 1954), p. 3. nla.gov.au/nla.news-article50137810

Legacy of the Dunera Boys

After the war, the men who had been interned at Hay and endured the Dunera voyage maintained strong bonds. They held regular reunions, gathering from across Australia to reconnect and reflect on their shared experiences.

Learning activities

These activities explore British wartime policies on internment and transportation, and how these decisions reflect broader attitudes toward colonies, refugees and perceived enemies.

Activity 1: Comparing wartime transportation of prisoners

During World War II, Britain transported prisoners to overseas territories due to overcrowded prisons—similar to earlier practices in colonial history.

- Introduce students to the historical context of prisoner transportation, including:

- Britain’s transportation of convicts to Australia in the 18th and 19th centuries

- The transportation of ‘enemy aliens’ during World War II

- Ask students to compare these two practices:

- What were the reasons behind each decision?

- What do these actions suggest about how the British government viewed its colonies or dominions at the time?

- Hold a class discussion on:

- Whether the use of overseas territories for imprisonment was a practical, political, or cultural decision

- What these decisions might reveal about Britain’s attitudes toward non-British subjects

Activity 2: Animosity toward ‘enemy aliens’

Even when people had fled persecution or supported the Allies, some Australians still demanded their internment.

- Provide students with background on the changing classification of ‘enemy aliens’ after February 1942.

- Those fleeing persecution or from allied nations were legally distinguished from enemy sympathisers and POWs.

- Ask students to reflect on and discuss:

- Why might some Australians still have demanded that all ‘aliens’ be imprisoned?

- What fears, assumptions or justifications were used to support these views?

- Are there modern parallels in how refugees or minority groups are treated during crises?

Activity 3: Listening to Michael Brent’s oral history

First-hand accounts help bring historical experiences to life.

- Introduce students to Michael Brent, a Dunera Boy whose story is recorded in the National Library of Australia’s oral history collection.

- Listen to part of his interview, starting at 1 hour and 7 minutes, where he begins discussing the Dunera voyage and internment in Hay.

- Ask students to:

- Use the subject headings to identify sections of interest

- Take notes on Brent’s experiences, impressions, and reflections

- Consider how this personal story adds to their understanding of the time period

- Hold a follow-up discussion or written reflection:

- What surprised them about his account?

- What emotions or perspectives did they take away?