Enemy aliens and war with Japan

Enemy aliens

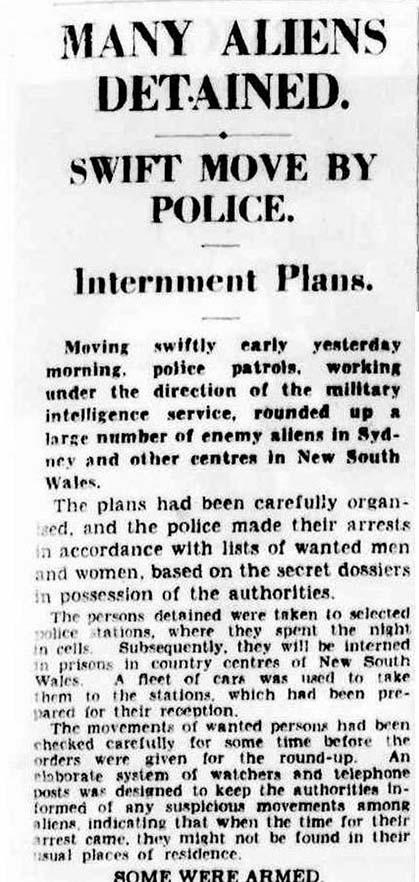

When war was declared in 1939, police across Australia acted quickly to address concerns about national security. German residents labelled as ‘enemy aliens’—a term also used during World War I—were detained based on pre-prepared lists.

Within hours, 257 people were taken from their homes. Many more would follow.

MANY ALIENS DETAINED, The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 11., 5 September 1939, nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17631257

MANY ALIENS DETAINED, The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 11., 5 September 1939, nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17631257

The announcement caused fear among German communities in Australia. Memories of World War I internments were still fresh. The early arrests signalled that residency in Australia offered no protection from suspicion.

Some Australians, however, warned against hysteria. Maurice Blackburn, a Melbourne lawyer and politician, urged restraint:

I warn Australians against being provoked into any discrimination against the vast number of people of German extraction in this country.

Legal basis for internment

The National Security Act 1939, passed on 8 September, gave the government broad powers. These included:

- Internment

- Surveillance

- Restrictions on movement and property

This legislation was more extensive than the War Precautions Act 1914 used during World War I.

Initially, military instructions stated that internment should only occur when other forms of control were inadequate. However, membership in Nazi or Fascist organisations was considered sufficient grounds for detention.

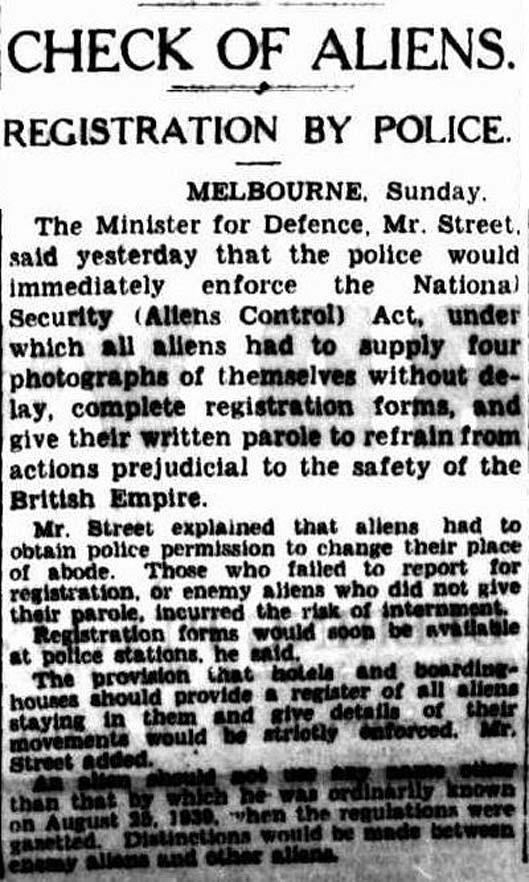

Registration and restrictions

As in World War I, widespread registration of ‘aliens’ was enforced. People over the age of 16 had to:

- Register at local police stations

- Report regularly to Aliens Registration Officers

Non-compliance could result in arrest or internment.

Restrictions increased over time. Without a special permit, registered aliens could not own:

- Firearms

- Cameras

- Cars or boats

- Carrier pigeons

CHECK OF ALIENS. (1939, September 11). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 11. nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17644712

CHECK OF ALIENS. (1939, September 11). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 11. nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17644712

Civilian internees and prisoners of war

Unlike World War I, international law during World War II required a clear distinction between:

- Civilian internees

- Prisoners of war (POWs)

Although both groups were to be treated humanely, they were held in separate facilities under different regimes.

Escalation of internment

Initially, the government intended to intern only a select few. But as the war intensified, internment increased.

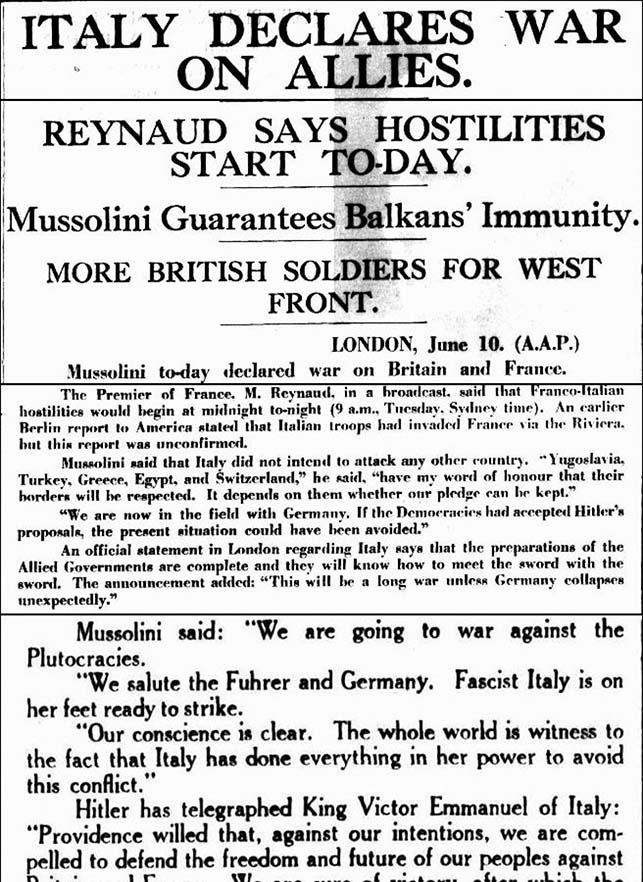

In April 1940, Germany invaded Denmark and Norway. By June, France had surrendered and Italy had joined the war. Britain stood alone, and fears of invasion grew.

Rumours of a ‘fifth column’—enemy sympathisers working to undermine Australia—spread rapidly. This led to increased internment of Germans and, after Italy’s entry into the war, Italians.

ITALY DECLARES WAR ON ALLIES. (1940, June 11). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 9. nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17679159

ITALY DECLARES WAR ON ALLIES. (1940, June 11). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 9. nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17679159

In Queensland, 103 Italians were arrested within a day. Many more followed, including women and children. Even British subjects—by birth or naturalisation—were not exempt.

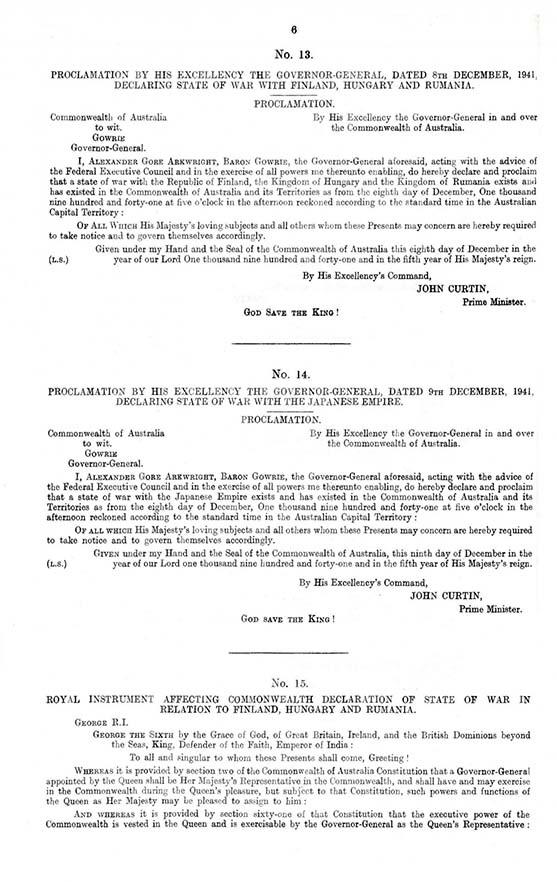

Australia. Parliament. (1941). Declaration of existence of state of war with Finland, Hungary, Rumania and Japan 8th December 1941 : documents relating to procedure of His Majesty's government in the Commonwealth of Australia. Canberra : Printed and published for the Government of the Commonwealth of Australia by L.F. Johnston, Government Printer nla.gov.au/nla.obj-1928613644

Australia. Parliament. (1941). Declaration of existence of state of war with Finland, Hungary, Rumania and Japan 8th December 1941 : documents relating to procedure of His Majesty's government in the Commonwealth of Australia. Canberra : Printed and published for the Government of the Commonwealth of Australia by L.F. Johnston, Government Printer nla.gov.au/nla.obj-1928613644

War with Japan

Worse was to follow. While Britain stood firm and avoided a German invasion, the Axis powers - including not just Italy but also Hungary, Rumania (now spelled Romania), Bulgaria and Finland - gained control of the front line from Dunkirk in France to the outskirts of Moscow, and from the coastal plains of Libya to the ports of Norway.

Then, with the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese in December 1941, Japan entered the fighting. A European war became a world war, and Australia felt threatened as never before. With the fall of Singapore in February 1942 and the bombing of Darwin just four days later, Australian anxieties reached fever pitch.

Internment numbers surged. By the end of the war, around 12,000 people from various backgrounds had been held in Australian internment camps.

Learning activities

These activities help students critically examine wartime language, propaganda, and the powers granted to governments during national emergencies.

Activity 1: Understanding the term ‘enemy alien’

During the world wars, people from certain backgrounds were labelled as enemy aliens—even if they had lived in Australia for many years.

- Ask students to reflect on the terms enemy alien or simply alien.

- What images or ideas do these words bring to mind?

- Do these terms carry fear, suspicion or other strong emotions?

- Discuss as a class:

- How can language like this influence public opinion or spread panic?

- Are there modern examples of language being used in a similar way?

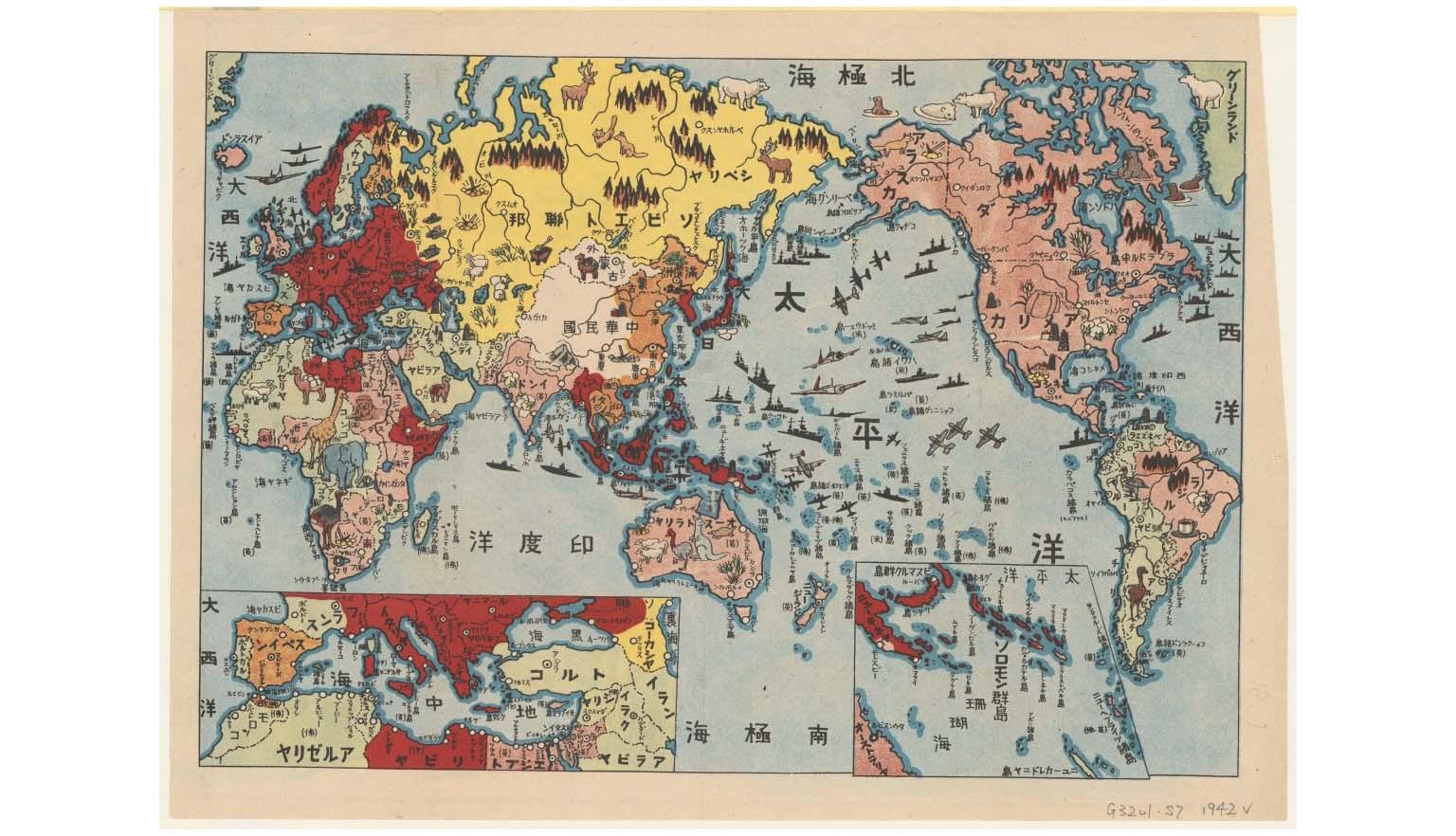

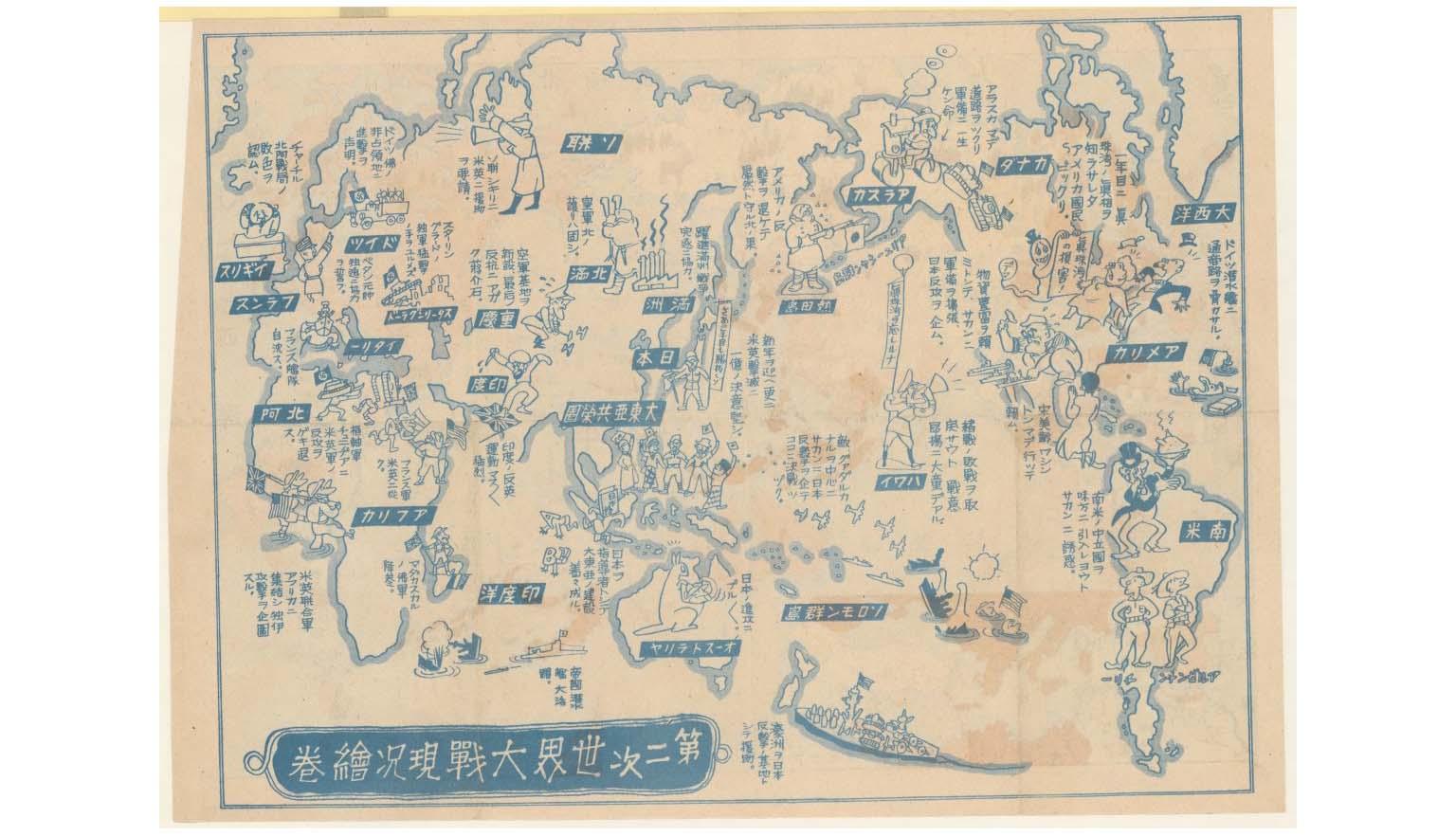

Activity 2: Analysing wartime propaganda

Maps and visuals were used during the war to shape public opinion, both in Australia and overseas.

- Provide students with a copy of the coloured Japanese map referenced in the resource.

- Ask them to examine the map closely and respond to the following questions:

- What is the purpose of this map?

- Who is the intended audience?

- How might someone living in Australia in 1941 have felt seeing this map?

Encourage students to think about fear, propaganda, and the emotional impact of visual material in wartime.

Activity 3: Government powers during crisis

Emergencies often lead to governments being given temporary powers that go beyond normal laws. This happened in both World Wars, and in other situations since.

- Ask students to research what powers the Australian Government had during:

- World War I

- World War II

- more recent crises (for example, COVID-19, bushfires, terrorism-related laws)

- Compare and discuss:

- How do the wartime powers compare with powers in modern emergencies?

- Were the powers temporary or long-lasting?

- What checks were in place to limit the government’s power?

This activity can be extended into a written reflection or group presentation.