War in Europe again - 'My melancholy duty'

Prime Minister Menzies’ 1939 radio address

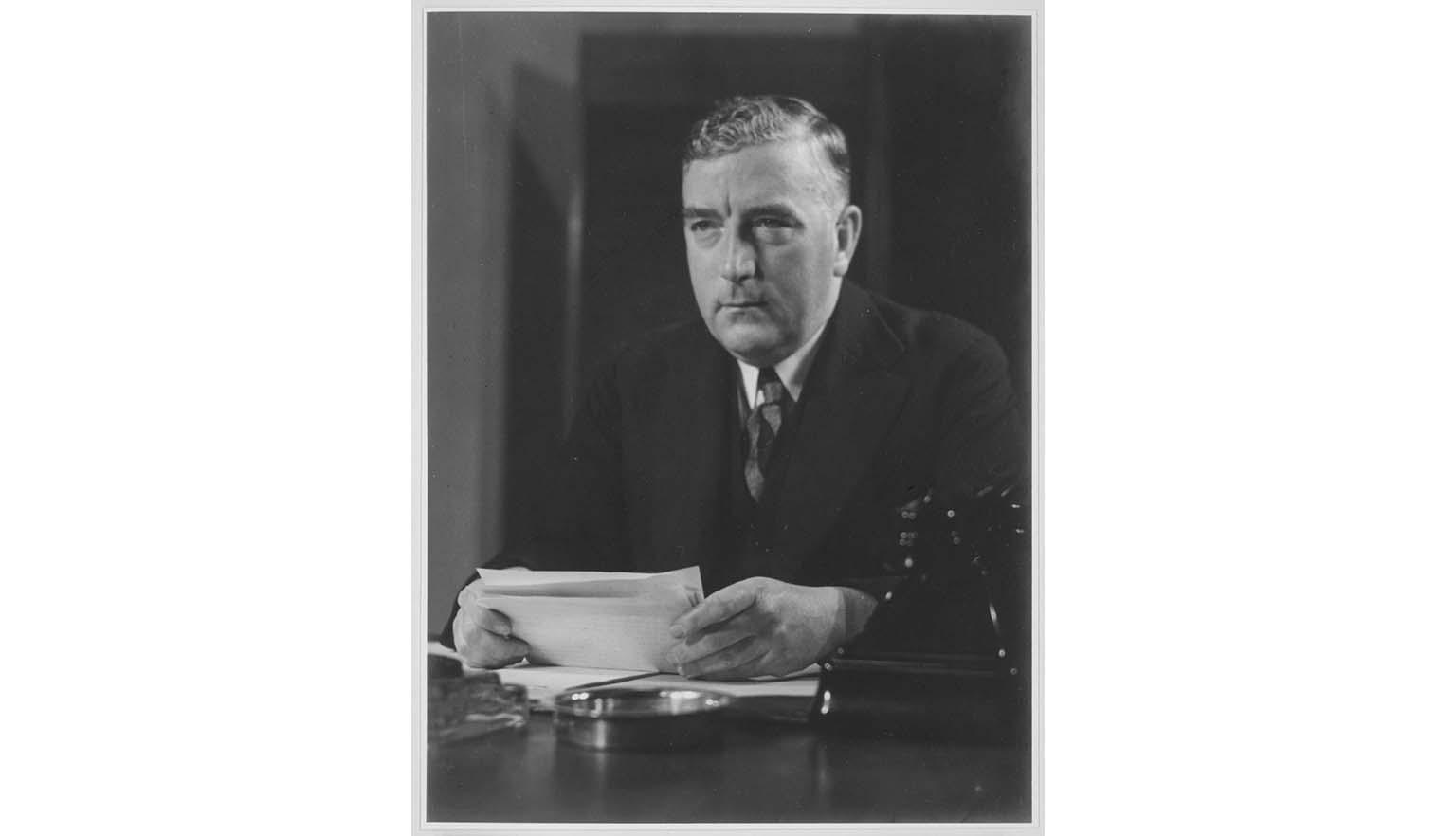

At 9.15 pm on Sunday 3 September 1939, Prime Minister Robert Menzies addressed the nation by radio to announce that Australia was at war with Germany.

At 9.15 pm on Sunday 3 September 1939, Australia’s Prime Minister, Robert Menzies (1894-1978), gave a radio address, announcing that Australia was at war with Germany:

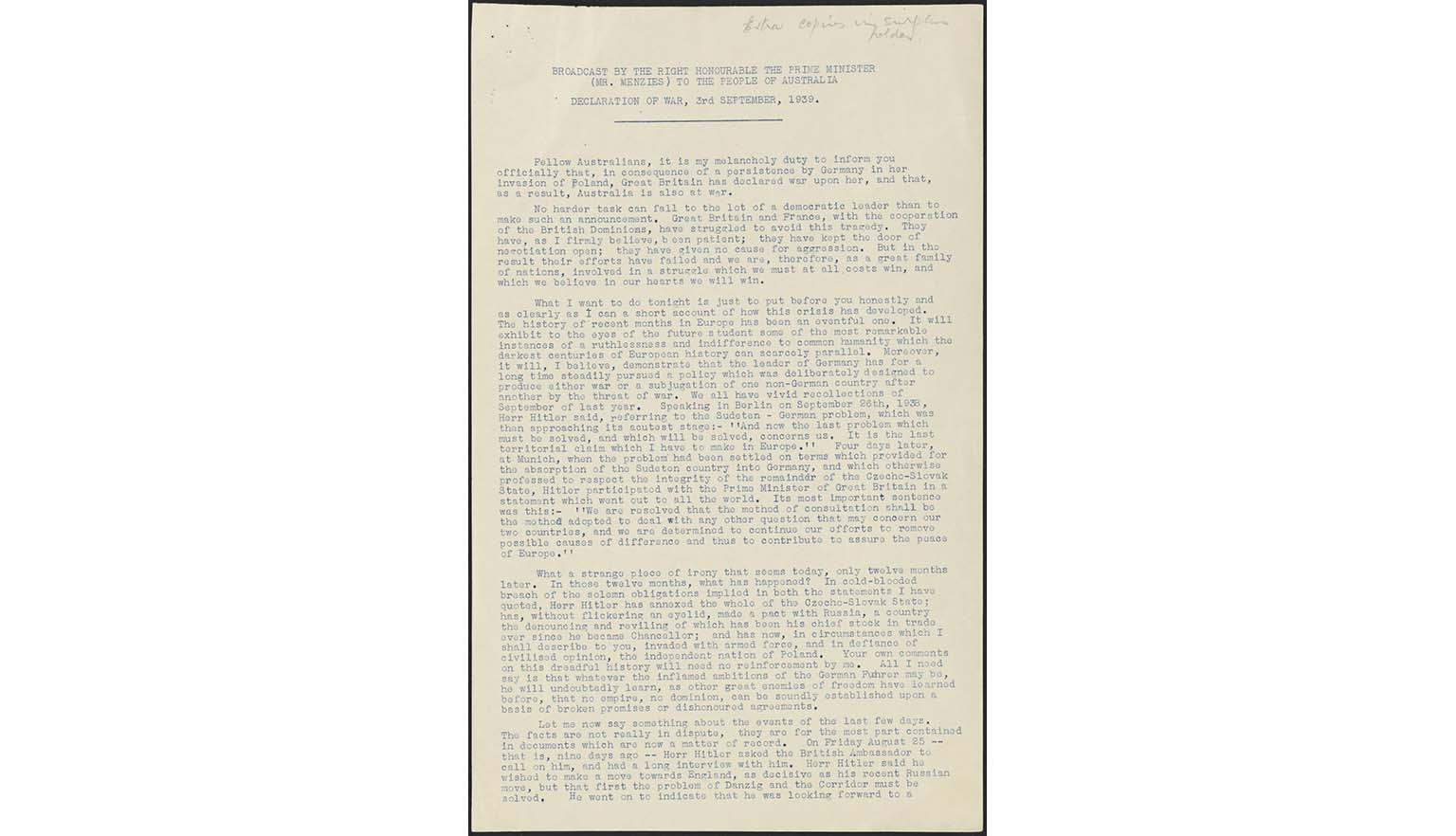

Fellow Australians, it is my melancholy duty to inform you officially that, in consequence of a persistence by Germany in her invasion of Poland, Great Britain has declared war upon her, and that, as a result, Australia is also at war.

The National Library of Australia holds key primary sources from this moment, including:

- A photograph of Menzies delivering the speech

- A sound recording of the broadcast

- A typed transcript of the address

In his speech, Menzies explained the two major events that led to Australia’s declaration of war. The first was the invasion of Poland by Germany.

German aggression

In 1933, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (better known as the Nazi Party), led by Adolf Hitler, came to power in Germany. Hitler quickly consolidated power and eliminated political opposition.

By the mid- to late 1930s, Nazi Germany had begun a program of militarisation and territorial expansion, justified by:

- Historical claims to neighbouring lands

- A desire for Lebensraum (living space) for the German people

Germany seized and annexed:

- Austria (1938)

- The Sudetenland (1938–39), a German-speaking region of Czechoslovakia

These actions were permitted under the Munich Agreement, an attempt by Britain and France to appease Germany.

When Germany threatened Poland, Britain and France signed a treaty guaranteeing Polish sovereignty. On 3 September 1939, after Germany invaded Poland, Britain and France declared war.

In cold-blooded breach of the solemn obligations … Hitler has annexed the whole of the Czechoslovak state; has, without flickering an eyelid, made a pact with Russia … and has now, under circumstances which I will describe to you, invaded with armed force and in defiance of civilised opinion, the independent nation of Poland.

Australian ‘Britishness’

The second reason Menzies gave for Australia’s declaration of war was Britain’s own declaration. At the time, Australia was a self-governing dominion of the British Empire. As such, Australia was expected to support Britain in war.

Menzies believed strongly in the Commonwealth, describing it as a “great family of nations” united by ancestry and allegiance to the Crown.

There can be no doubt that where Great Britain stands, there stand the people of the entire British world.

There was no parliamentary debate before the declaration. However, Menzies later wrote that the decision reflected the will of the people:

My announcement expressed the overwhelming sentiment of the Australian people … in 1939 neutrality for Australia in a British war was unthinkable unless we were prepared to add secession to neutrality.

In the 1930s, many Australians saw no conflict between being Australian and being British. Menzies referred to Britain as the “Mother Country”, reflecting a shared identity common at the time.

A just war?

In his speech, Menzies put forward arguments to justify why Australia should go to war. He outlined a commitment to an international cause - fighting fascism, German expansion and militarism:

It is plain, indeed it is brutally plain, that the Hitler ambition has been not, as he once said, to unite the German peoples under one rule but to bring under that rule as many European countries, even of alien race, as can be subdued by force.

If such a policy were allowed to go unchecked there could be no security in Europe and there could be no just peace for the world. A halt has been called. Force has had to be resorted to, to check the march of force. Honest dealing, the peaceful adjustment of differences, the rights of independent peoples to live their own lives, the honouring of international obligations and promises, all these things are at stake.

‘No harder task can fall to the lot of a democratic leader’

At the time he gave his famous address, Robert Menzies had been Prime Minister for just over four months. Following the death in office of Joseph Lyons in 1939, Sir Earle Page, leader of the Country Party, had been appointed as a caretaker prime minister while the governing United Australia Party (UAP) chose a new leader.

When Menzies, the former Attorney-General and Minister for Industry was voted in narrowly by the UAP party room, Page refused to serve with him (he would have preferred the return of Stanley Bruce to politics and the party leadership). Page resigned and withdrew his Country Party from the coalition and Menzies became prime minister.

Falk Studios (Firm), Portrait of Sir Earle Page, 1939, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136266546

Falk Studios (Firm), Portrait of Sir Earle Page, 1939, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136266546

Less than two weeks after his radio address, Menzies formed a War Cabinet. This collection of Government ministers would shape Australia’s decision-making in relation to the conflict.

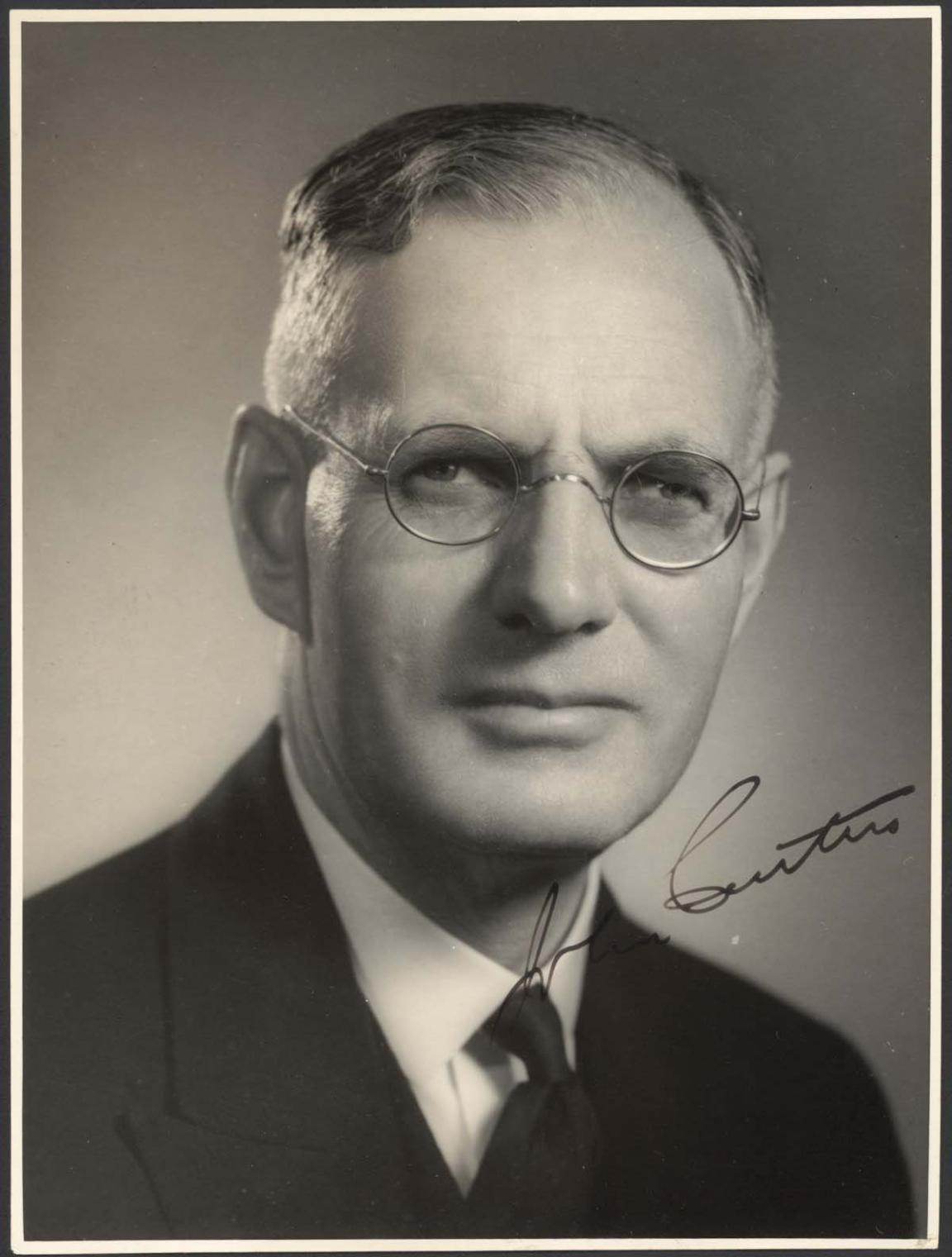

Autographed portrait of John Curtin, Prime Minister of Australia, 1941-1945, 1941, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-137128033

Autographed portrait of John Curtin, Prime Minister of Australia, 1941-1945, 1941, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-137128033

When the 1940 election resulted in a hung parliament and a minority UAP government, Menzies suggested a government of national unity to see out the duration of the war. The ALP had decided at a conference before the election that it would not support such a move:, its leader John Curtin suggesting instead an Advisory War Council, where the Government and opposition would have equal representation.

‘What may be before us we do not know, nor how long the journey’

During Menzies’ wartime prime ministership (1939–1941), Australia sent Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) aircrews and a number of Royal Australian Navy (RAN) ships to fight for Britain.

The Australian Army did not engage in combat until 1941, when three divisions joined the fight in the North African and Mediterranean zones of conflict, most famously halting the Wehrmacht (Germany’s armed forces) at Tobruk, in North Africa.

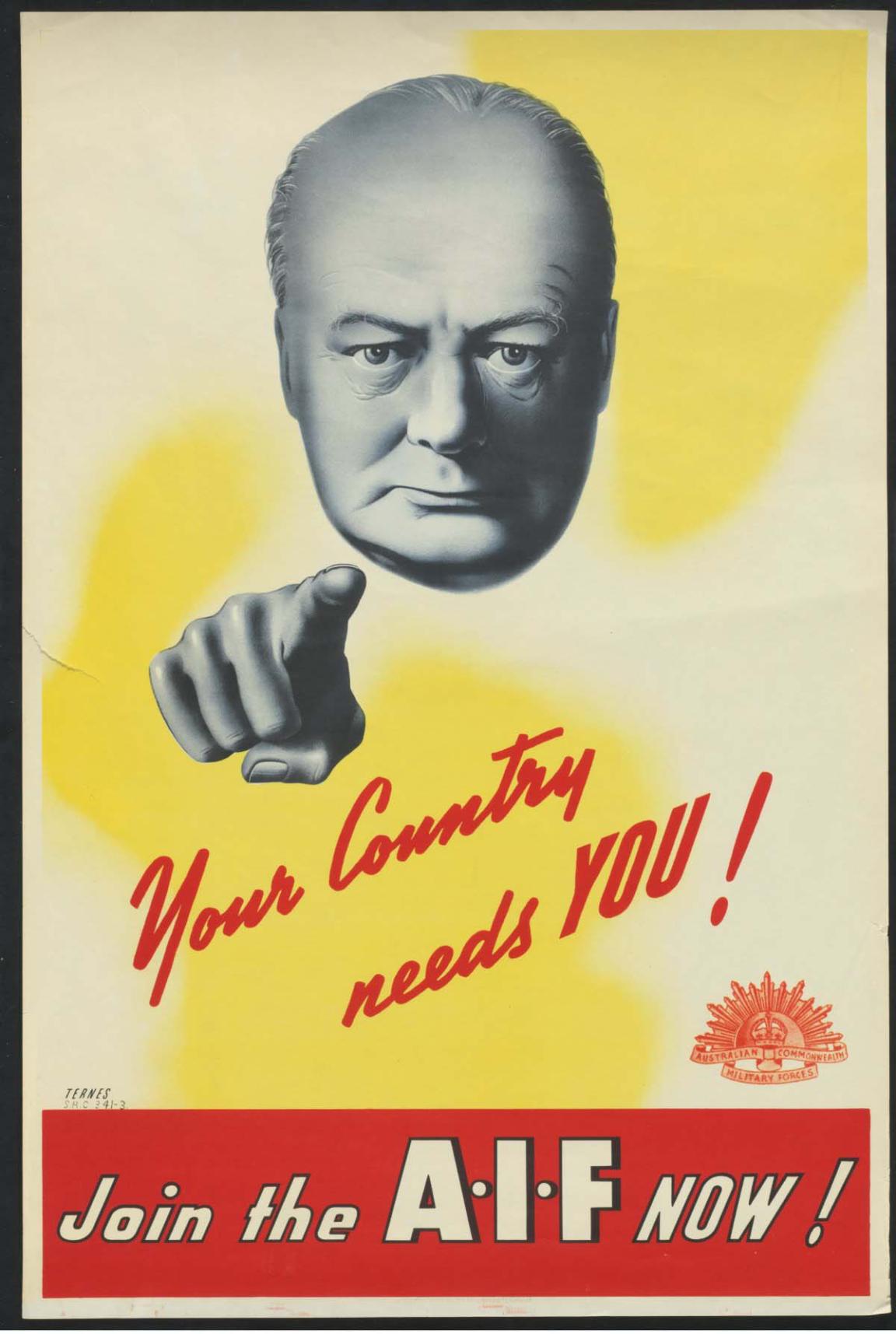

Australia. Army. Australian Imperial Force, 2nd (1939-1946) & Ternes. (1940). Your country needs you! Join the A.I.F. now!, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-137975181

Australia. Army. Australian Imperial Force, 2nd (1939-1946) & Ternes. (1940). Your country needs you! Join the A.I.F. now!, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-137975181

Australia became inextricably committed to the war. Posters were an easy way to recruit for the armed forces. This striking Australian recruitment poster features British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. It echoes the famous World War 1 British recruitment poster, which had so successfully used Lord Kitchener’s steely gaze, his pointing finger and the same words.

Despite the general support for Australian involvement, in the early years the war still seemed distant. People were reluctant to make sacrifices.

This was especially the case during the period between the Allied declaration of war in September 1939 and the beginning of major military operations, a time often referred to as the ‘Phoney War’.

Menzies had called for a business-as-usual attitude during this period, but in mid-1940, as German troops marched through Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg on their way to Paris, the Prime Minister would have great difficulty shifting the nation’s outlook to that of a ‘total war’ home front.

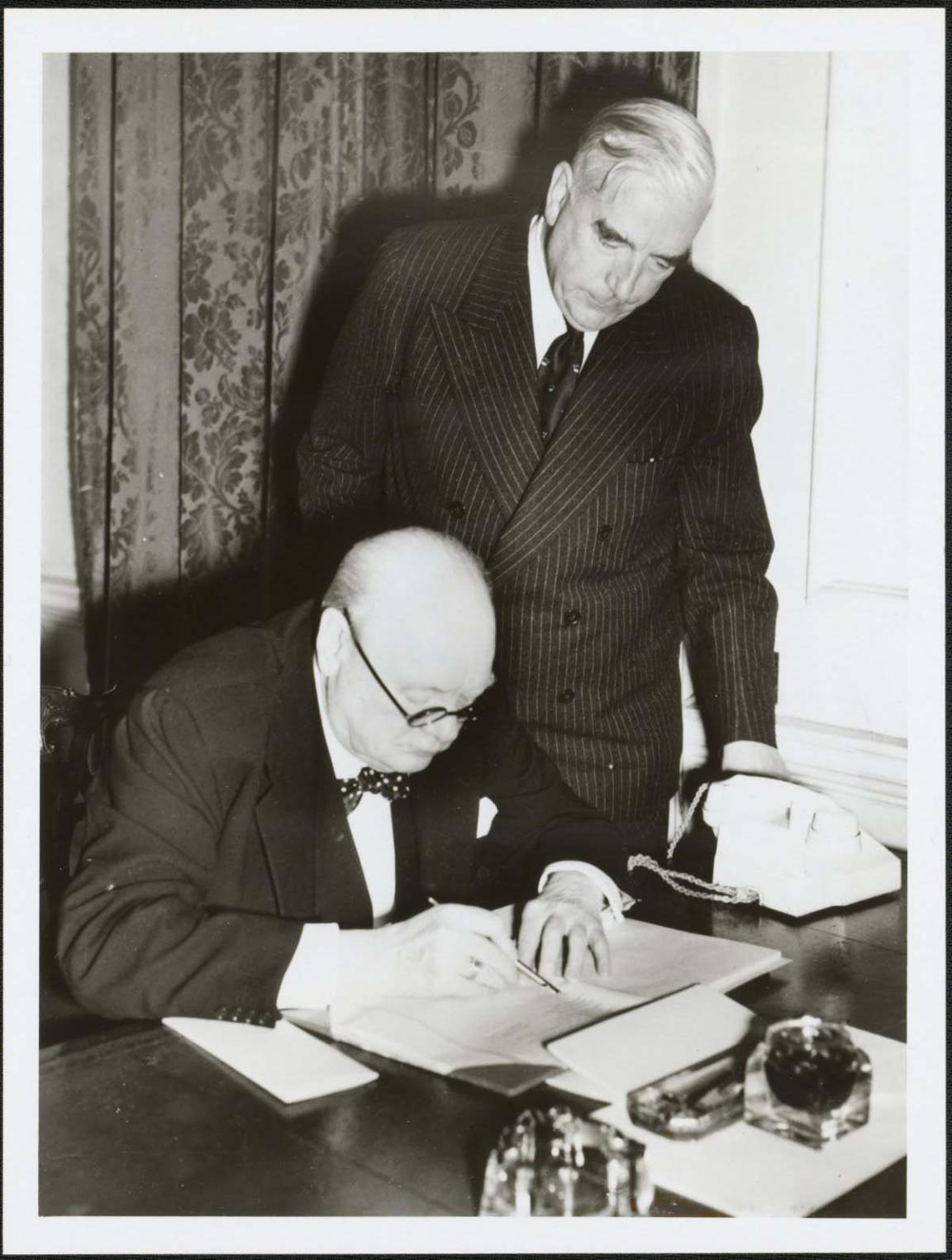

Portrait of Prime Ministers R.G. Menzies and Winston Churchill at Downing Street, London, 1941, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-137388175

Portrait of Prime Ministers R.G. Menzies and Winston Churchill at Downing Street, London, 1941, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-137388175

In January 1941, Menzies travelled to London. He spent four months:

- Attending Churchill’s War Cabinet

- Seeking reinforcements for Singapore

- Lobbying the United States for support

His extended absence drew criticism. Some speculated he aspired to replace Churchill as British Prime Minister. On returning to Australia, Menzies found he had lost the support of his party. The independents who had supported his minority government withdrew, and John Curtin became Prime Minister.

Learning activities

Use these activities to explore Australia’s relationship with Britain during World War II, the idea of a "just war", and how leaders communicate in times of crisis.

Activity 1: Australia and Britain: A colonial connection

Australia’s entry into World War II was closely tied to its strong historical ties with Britain.

- Start with a class discussion:

- Why did Australia follow Britain into war in 1939?

- What does this suggest about Australia’s political identity at the time?

- Introduce Menzies’ statement: “British to my boot heels.”

- Ask students to investigate Menzies’ family background and political beliefs.

- Were most Australians seen—or did they see themselves—as British?

- Was there a conflict between being ‘British’ and being ‘Australian’?

Activity 2: What is a ‘just war’?

Throughout history, philosophers have tried to define what makes a war morally acceptable.

- Divide the class into small groups. Ask each group to:

- Research the concept of a just war, with reference to Cicero and Thomas Aquinas.

- Discuss what makes a war ‘just’ or ‘unjust’.

- Have each group consider and respond to the following questions:

- Can a war ever truly be just?

- Was World War II a just war?

- How does it compare to later conflicts like Vietnam, Iraq or Afghanistan?

- Would you have chosen to enlist in each of these wars? Why or why not?

Activity 3: Write a wartime address

World leaders use speeches to rally, comfort and inform the public during crises. In 1939, Prime Minister Robert Menzies addressed the nation to declare war on Germany.

- Ask students to imagine they are a speechwriter for a head of government in September 1939.

- Their task is to draft a short national address in response to the outbreak of World War II.

- What tone would they use—serious, hopeful, determined?

- What key words, values or emotions would they include?

- Compare their speech with the one delivered by Menzies.

- What’s similar? What’s different?

- How does language reflect leadership and national identity?

- Have students:

- Swap speeches with a classmate

- Read each other’s speeches aloud to the class