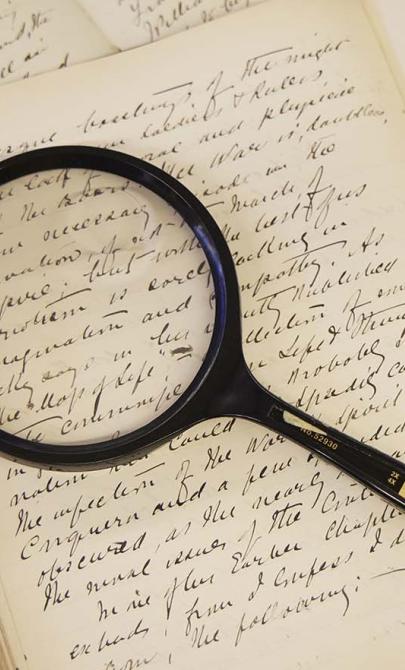

Documentary evidence

About documentary evidence

Documentary evidence includes written and visual records that provide insight into the past. These sources help us understand what life was like, what people thought, and what challenges they faced.

Examples include:

- Diaries

- Letters

- Contracts

- Wills

- Official documents

- Drawings and paintings

- Newspapers (later periods)

- Photographs and film (modern times)

These sources can reveal details about:

- Daily life and personal experiences

- Social and political structures

- Economic conditions

- Health and wellbeing

- Cultural and religious practices

Literacy and access

Throughout most of history, literacy rates were low. In medieval western Europe, fewer than 20% of people could read or write.

Those who were literate were usually members of the upper classes, royalty or the church. As a result, most surviving documents reflect the lives of the wealthy and powerful.

However, historians can still learn about everyday life through:

- Contracts and receipts

- Church records

- Court documents

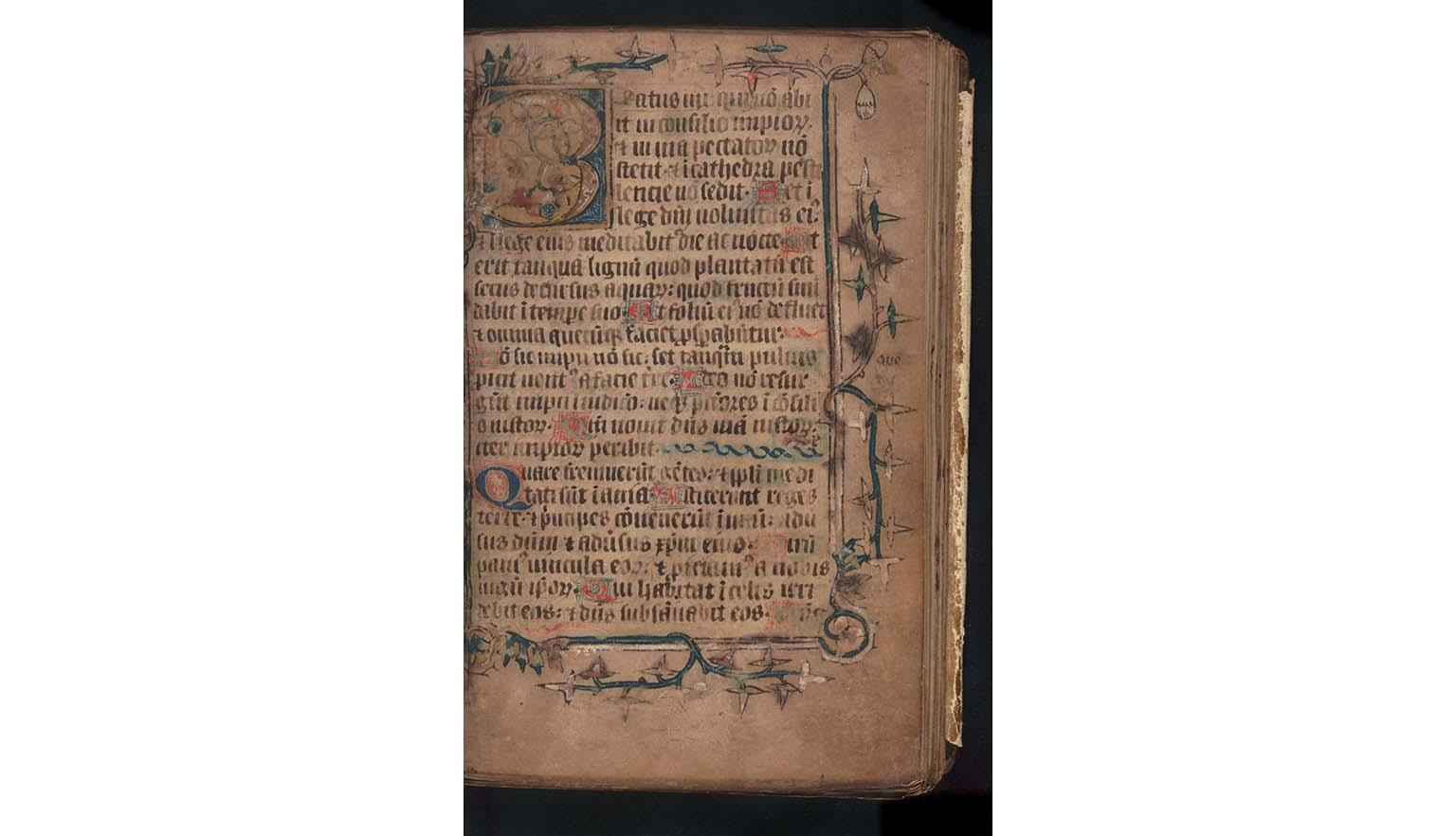

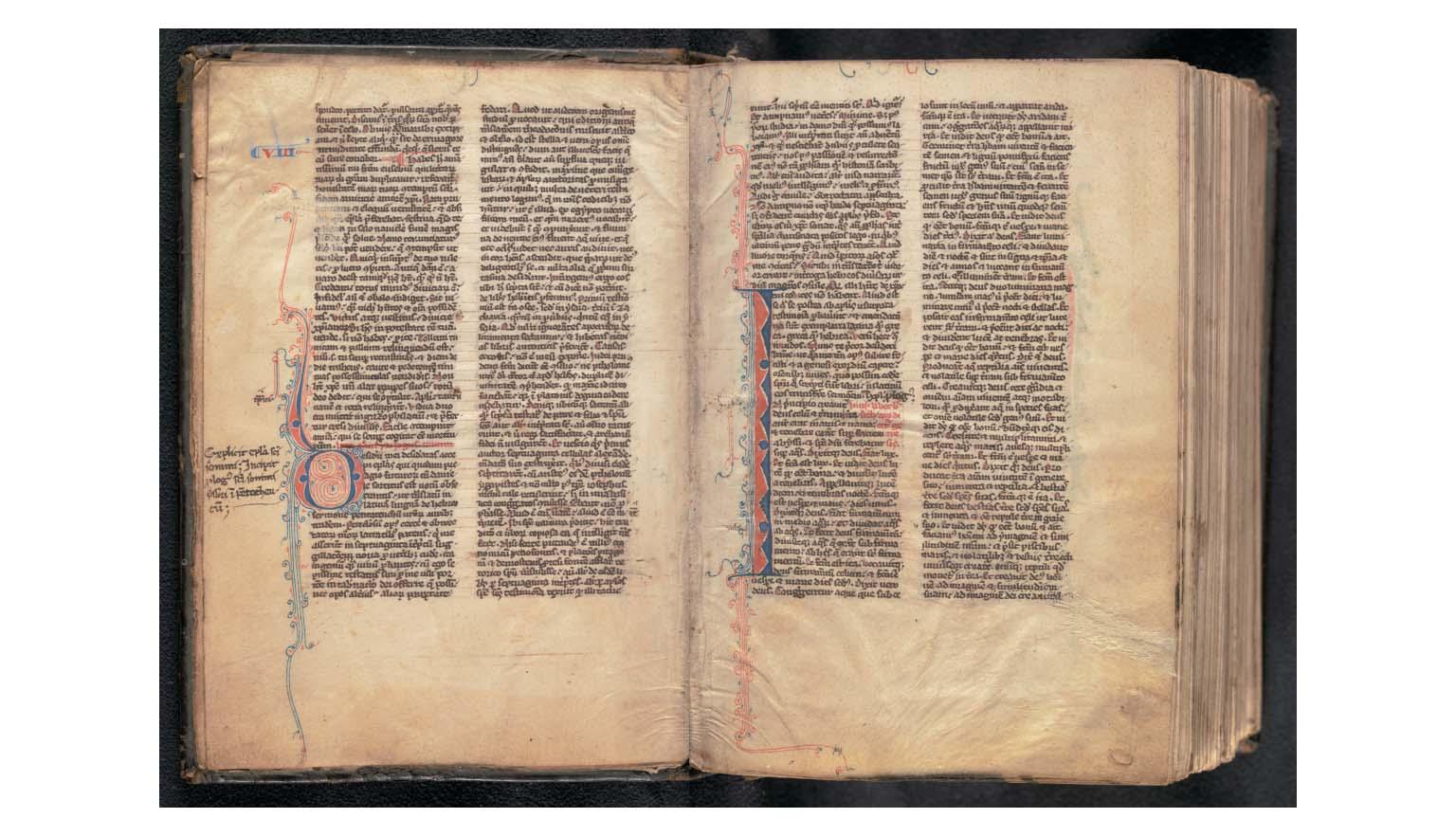

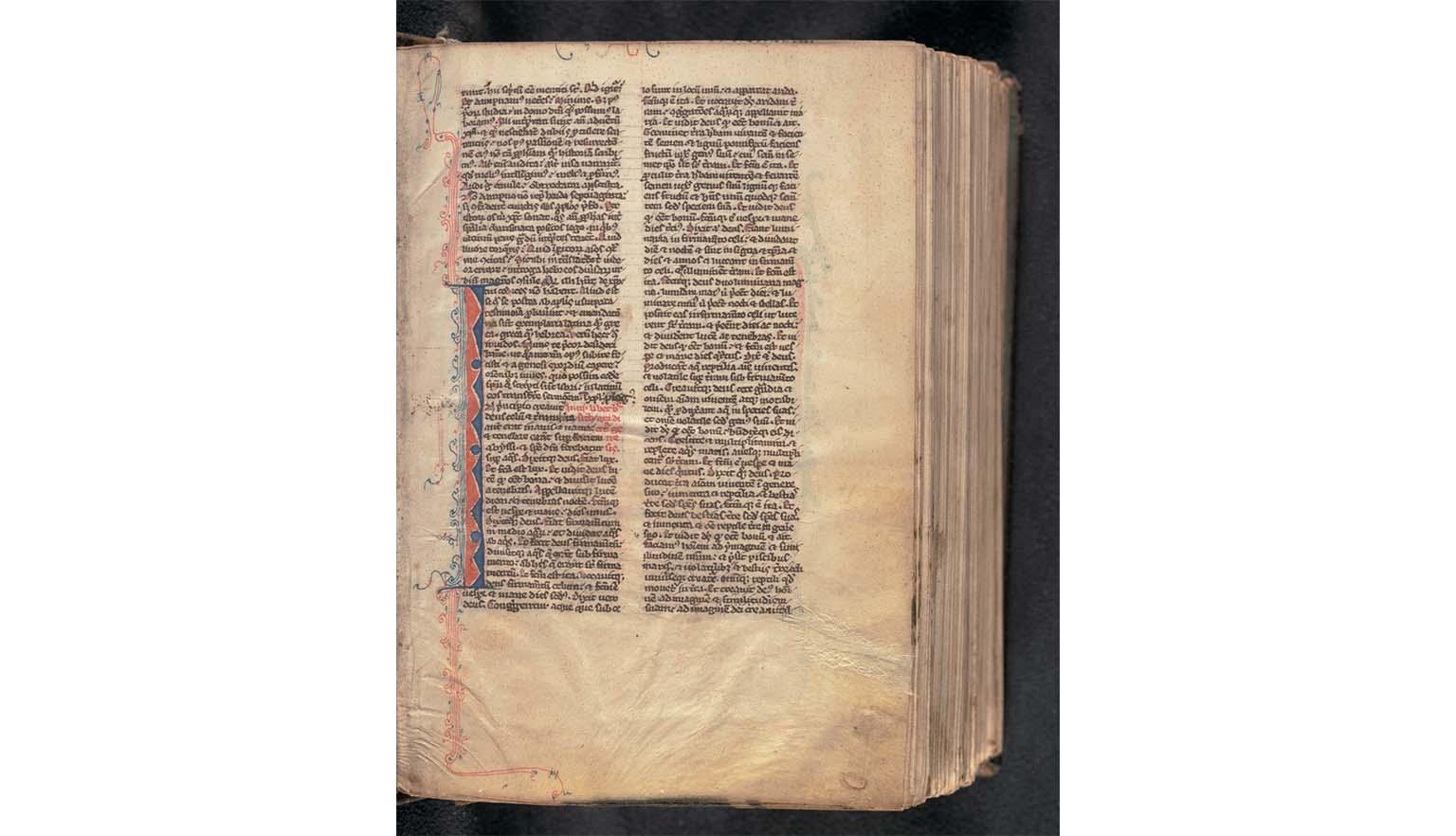

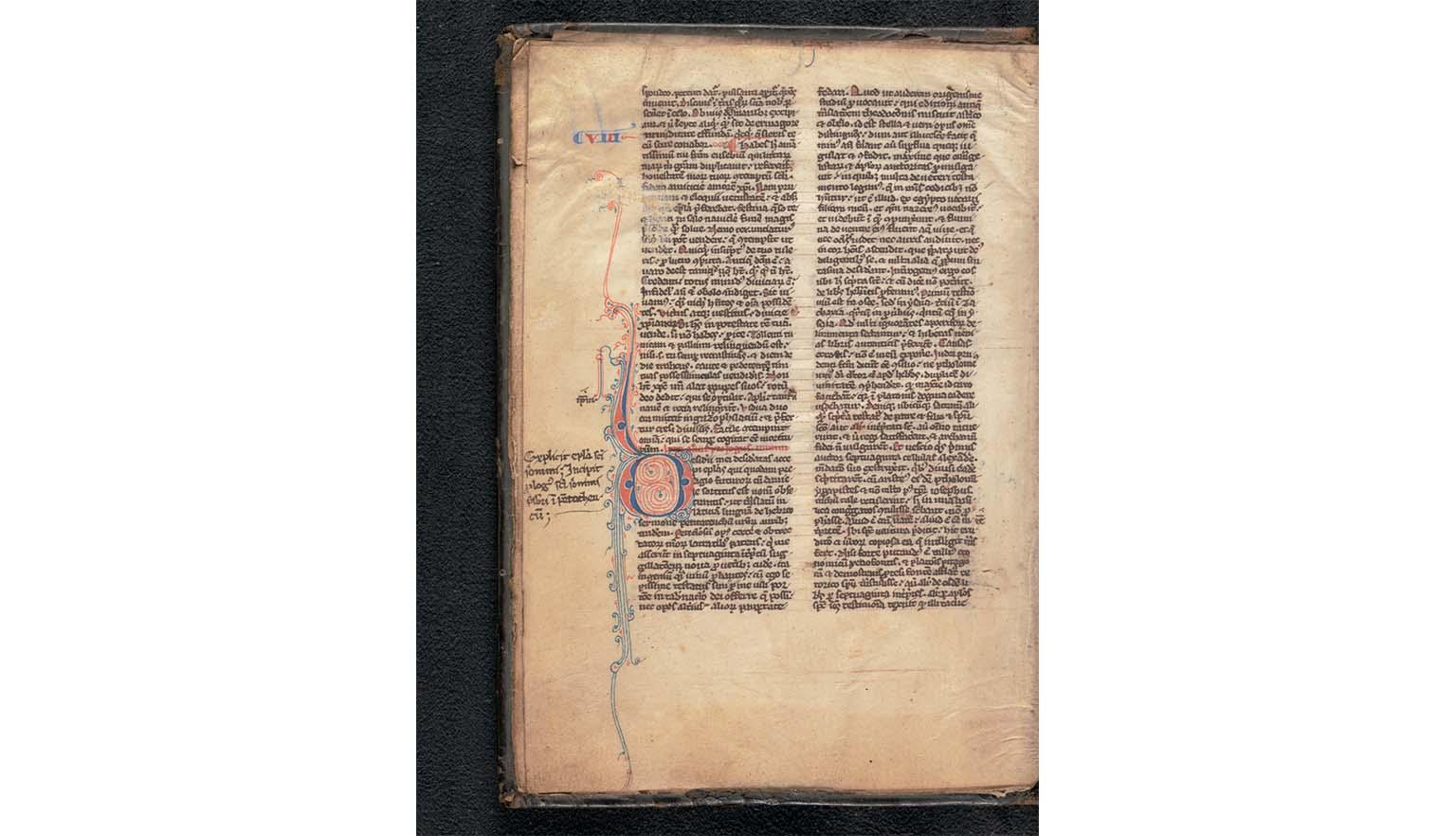

The Library holds a rich collection of medieval manuscripts and early books, both religious and secular, dating from the 11th century CE to the Renaissance. These items have been acquired through donations, bequests and purchases.

A faithful history

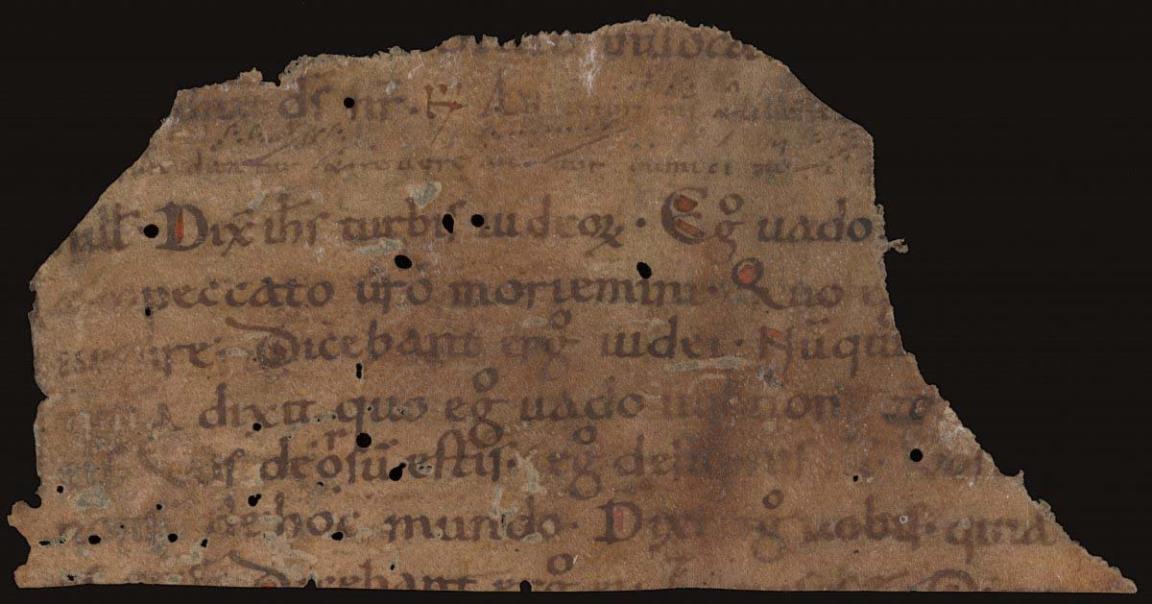

The oldest item in the Library’s collection is a small fragment from a breviary—a book of prayers used by clergy. It dates from the 10th century and comes from England.

The text is from the Book of John (chapter 8, verses 21–29), where Jesus predicts his death and speaks of his divine mission. The musical notation is a gradual, a sung part of a Catholic mass.

MS 4052-Medieval manuscripts and documents from the Nan Kivell calligraphy collection, circa 10th century-1819/Series 2/Item 16/Recto 16. Musico-litergical documents/ Fragment from a missal. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-214214193

MS 4052-Medieval manuscripts and documents from the Nan Kivell calligraphy collection, circa 10th century-1819/Series 2/Item 16/Recto 16. Musico-litergical documents/ Fragment from a missal. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-214214193

This religious text helps us understand how faith was practised and experienced in medieval times.

Digital Classroom: Fragment from a Breviary

Language and change

Another document, written two to three centuries later, is also a gradual or missal—a guide for conducting religious services. It contains musical chants used during mass.

Latin remained the official language of the church and government in medieval Europe long after the fall of Rome. It is still used today in Vatican City and some Catholic services.

Early English examples

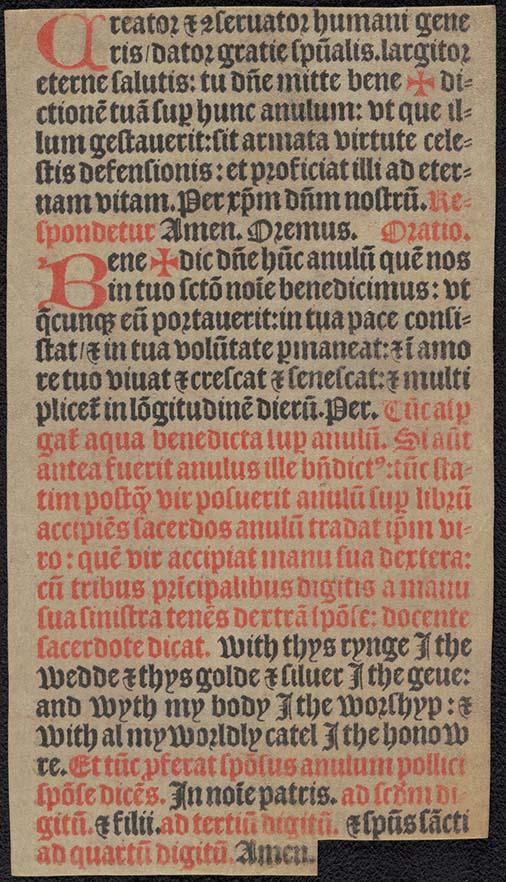

By the early 16th century, English began appearing alongside Latin in religious texts. One example is a wedding ceremony script from England. While most of the text is in Latin, the responses spoken by the couple are in early English.

The passage reads:

With this ring I thee wed and this gold and silver I thee give: and with my body I thee worship: and with all my worldly catel [chattels] I thee honour.

Rex Nan Kivell, Medieval manuscripts and documents from the Nan Kivell calligraphy collection, Series 3/Item 36/Verso 36 Religious Text, 1819, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-229328970

Rex Nan Kivell, Medieval manuscripts and documents from the Nan Kivell calligraphy collection, Series 3/Item 36/Verso 36 Religious Text, 1819, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-229328970

This early English is still understandable today, though the spelling is inconsistent. Before the late 19th century, there were no standard spelling rules. Words were often written phonetically, which helps historians understand how people may have spoken.

For example, the phrase “With this ring” appears as “Wyth thys rynge”. The use of “Y” instead of “I” was common in early English. Latin, however, did not use the letter “Y” in native words.

Administration of the land

Laws help those in power govern effectively. They set expectations for everyone—including the monarch—and outline consequences for breaking them. In medieval times, the legal system was complex. Laws, policies and decrees were written down and distributed across the kingdom. Because most people could not read, a herald would read new laws aloud in public places.

A record of the economy

A strong economy relied on trade and a network of industries. To keep the system running smoothly, it was important to record contracts, debts, indentures and business agreements.

Since farming and production were the main sources of employment for ordinary people, economic and legal documents offer valuable insights into their lives.

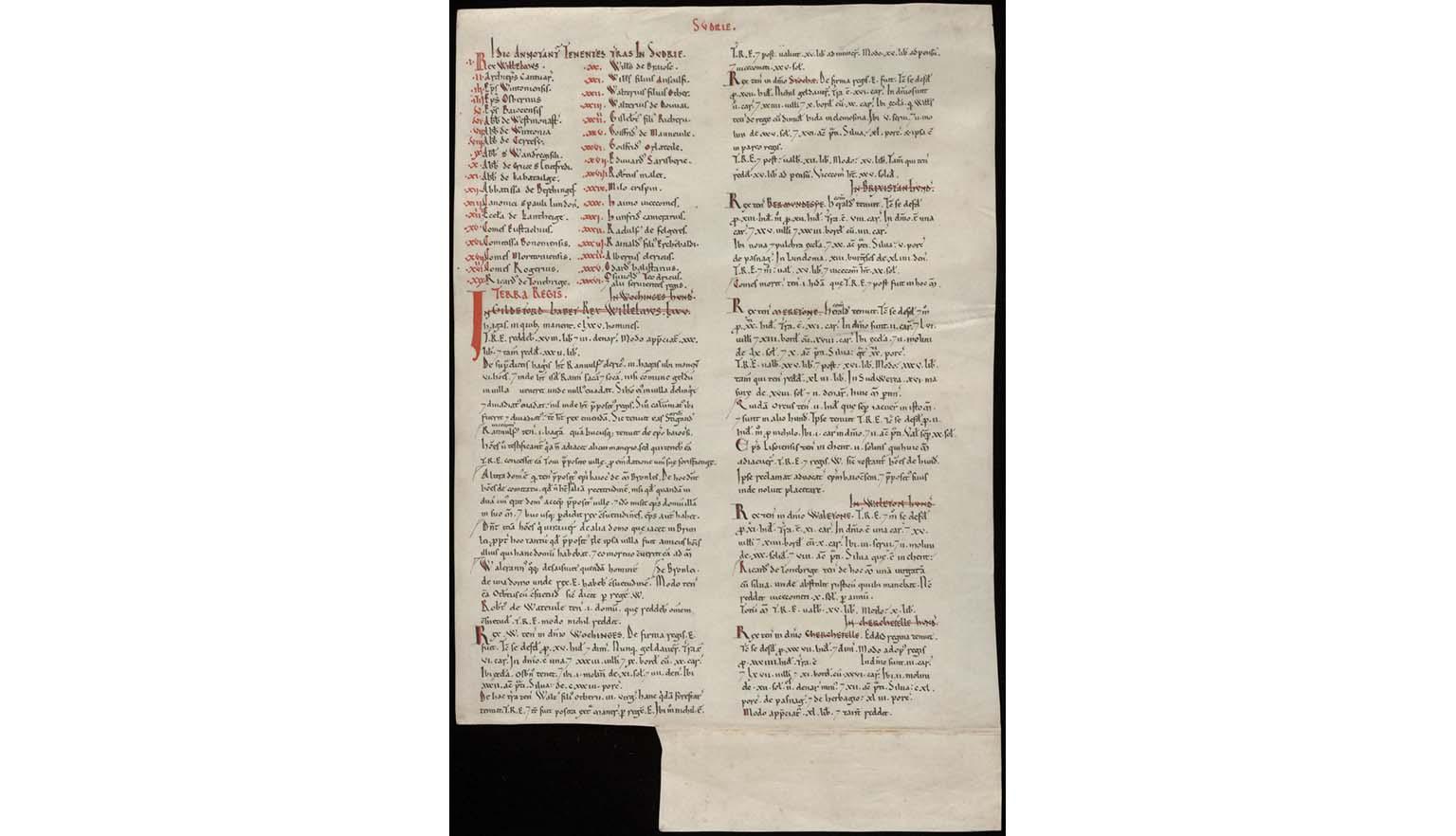

The Domesday Book

One of the most significant administrative records from medieval England is the Domesday Book (also spelled Doomsday Book). It was commissioned by William the Conqueror in 1086 CE to survey land ownership in England and parts of Wales.

The Domesday Book recorded:

- Who owned which land

- How much land was held

- How many people lived there

- What taxes were owed to the Crown

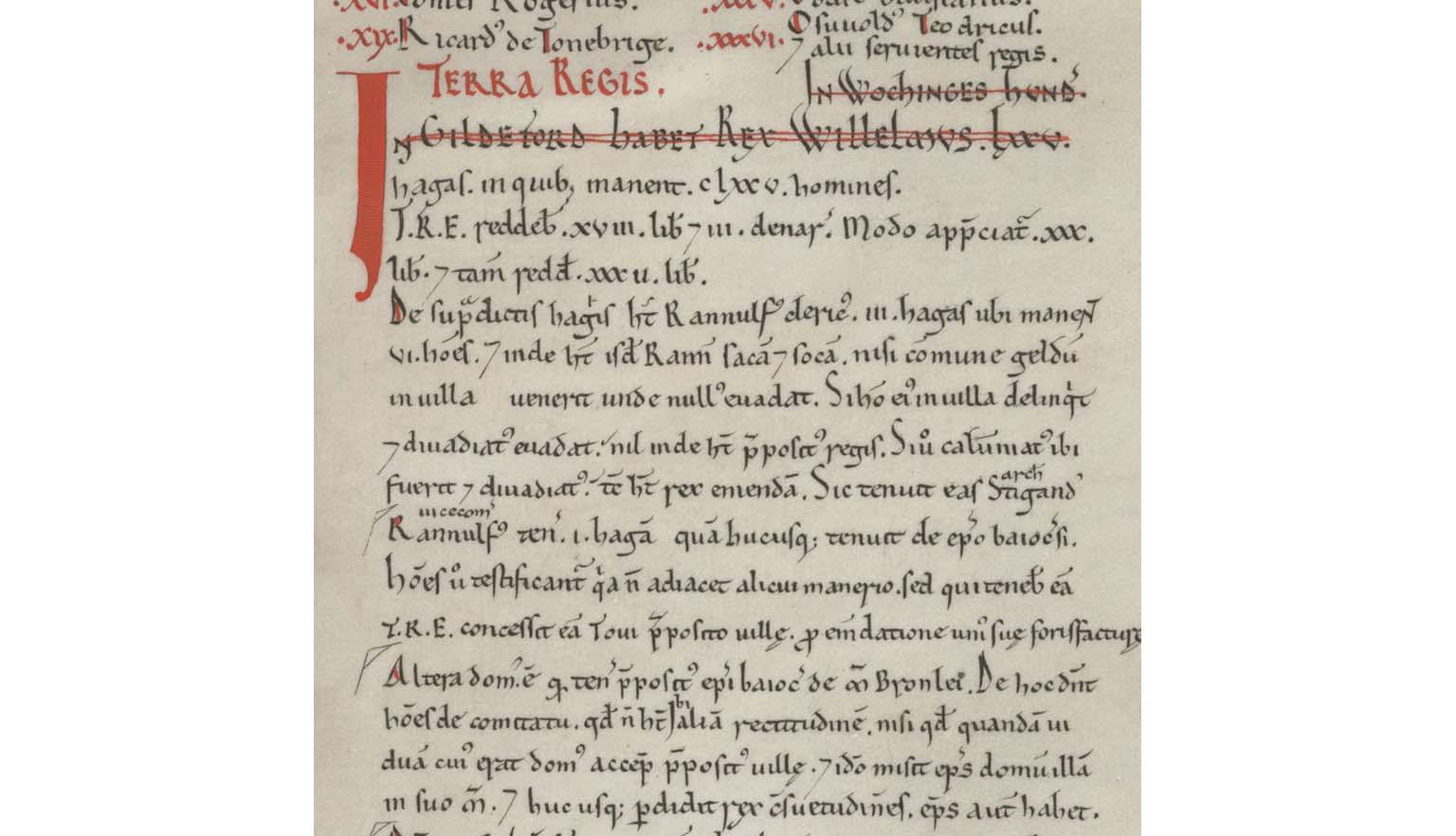

The Library holds a copy of a page from the Domesday Book, printed around 1861. While not medieval itself, it closely resembles the original. This page lists landholders in the county of Surrey (Sudrie), with King William (Rex Willelmus) at the top.

Historical context

The Domesday Book includes the abbreviation T.R.E., which stands for Tempore Regis Edwardii—“in the time of King Edward”. This refers to Edward the Confessor, who died without an heir in January 1066.

Several claimants to the throne emerged:

- Harold Godwinson, Earl of Wessex (England)

- Harald Hardrada, King of Norway

- William, Duke of Normandy (France)

Harold was crowned king, but both Harald and William invaded. Harald was killed at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in September 1066. Harold was killed at the Battle of Hastings in October 1066. William became king in December 1066—an event known as the Norman Conquest.

Excerpts

The Domesday Book provides detailed information about land ownership, population, and taxation.

In Woking Hundred:

In Guildford, King William has 75 sites, whereon dwell 175 men.

Before 1066 they paid 18 0s 3d; now they are valued

at 30; however, they pay 32.

This entry shows how land value and taxation changed after the Norman Conquest.

The document also records:

- The number of ploughs and tools on each estate

- The presence of churches, mills and woodlands

- How land changed hands

Ranulf the sheriff holds one site which he held hitherto from the Bishop of Bayeux.

But the men [of the County] testify that it is not included in any manor, but that before

1066 its holder granted it to Tovi, the town reeve, in payment of one of his fines.

Units of land measurement

The Domesday Book used terms unfamiliar today:

- Hundred – A subdivision of a shire or county (similar to a modern council area)

- Hide – A unit used for tax purposes, roughly equal to 50 hectares

- Virgate – A smaller unit; four virgates made up one hide

Changes in taxation

The Domesday Book shows how taxes increased after 1066. For example:

In Wallington Hundred:

Archbishop Lanfranc holds Croydon in lordship.

Before 1066 it answered for 80 hides; now for 16 hides and 1 virgate.

Land for 20 ploughs. In lordship 4 ploughs;

48 villagers and 25 smallholders with 34 ploughs. A church.

A mill at 5s; meadow, 8 acres; woodland at 200 pigs.

Total value before 1066 and later 12; now 27 to the Archbishop; to his men 10 10s.

Women and land ownership

Although the system favoured men, some women held land in their own names:

In Elmbridge:

Aldgyth of Elmbridge, a woman, holds 1 virgate from the King. Value 3s.

-------

The Bishop also has 1 further hide there. A widow holds it and

held it before 1066; she could go where she would. Then it

answered for 1 hide; now for nothing. Value 10s.

The University of Hull has an English transcription of the Domesday Book.

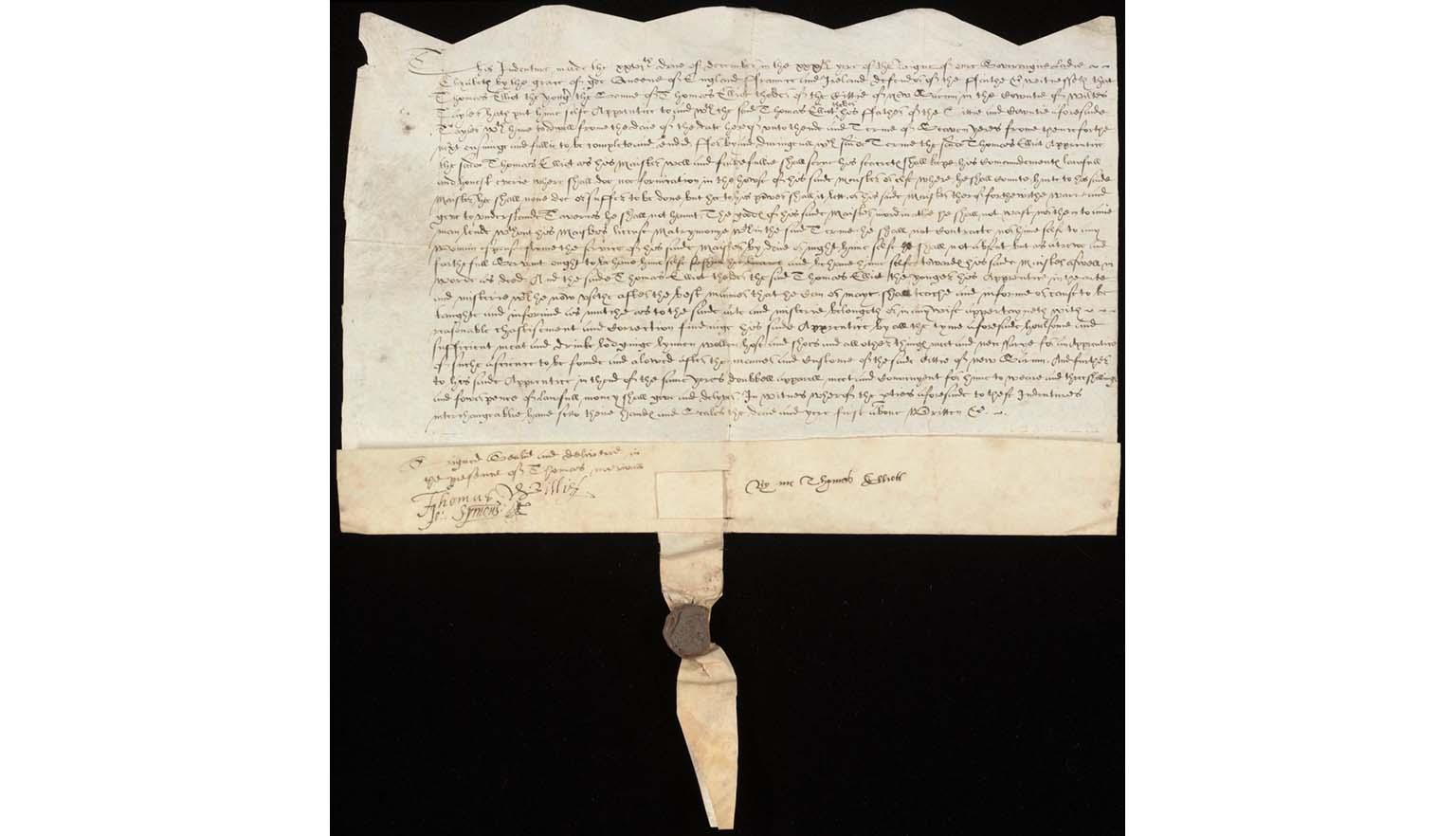

Indentured service

One of the key features of the medieval European feudal system was the use of indentured service.

The word indenture refers to a deed, contract or sealed agreement between two or more parties, where one person is bound to serve another. Originally, indentures described agreements between a master and an apprentice. Over time, the term came to include any system where a person was bound to work for someone else, often with limited choice.

The word comes from the Middle English endenture, derived from the Old French endenteure. It refers to the jagged or indented edges of these documents, which were used to verify authenticity. Only the original copies would fit together perfectly.

Digital Classroom: Lease of Indenture

A historical example

These documents are a pair of indentures dated 26 December 1587, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. They are between Thomas Elliot the younger and his father, Thomas Elliot the elder.

Each party would have received a copy. The contract with the long seal tag is signed “by me Thomas Elliot”, while the other is signed “X Ellyott Senioris” (Elliot Senior).

They are written in English and many words are readable; however, the old style of handwriting makes it very difficult to decipher. The documents are made of parchment, a writing surface made from the specially prepared skins of sheep or goats.

The contract reads:

Thomas Elliot the yonger the sonne of Thomas Elliot thelder of the cittie of New Sarum, in the countie of Wiltes, 'tayler', to Thomas Elliott thelder, his father of the city and county aforesaid.

Today, “the cittie of New Sarum, in the countie of Wiltes” is known as Salisbury, in Wiltshire, England.

Terms of the indenture

Thomas the younger agreed to become his father’s apprentice for 7 years to learn the trade of tailoring.

This is a modern transcription of the contract’s terms but it preserves the original spelling, punctuation and grammar.

Thomas Elliot the Younger promises:

- to serve his master well and faithfully,

- to keep his secrets,

- to do his lawful and honest commandments,

- to do no fornication in his master's house or elsewhere,

- to do no hurt to his master or suffer any to be done, but shall lett or warn his master thereof,

- not to haunt taverns,

- not to waste his master's goods, nor lend them to any man without his master's licence,

- not to contract matrimony within the said term,

- not to absent himself from the service of his said master by day or night, and to bear himself as a true and faithful servant in word and deed.

Thomas Elliot the Elder promises:

- To teach his apprentice the trade of tailoring to the best of his ability

- To provide reasonable discipline and correction

- To supply food, drink, lodging, clothing and other necessities

- To give his apprentice double apparel and 3 shillings and 4 pence at the end of the term

Transcript of an apprenticeship indenture.

This transcript is the whole contents of the document. It includes original spelling, punctuation, and grammar.

(// indicates the end of a line of script as it is written on the original document)

This Indenture made the xxvith Daie of December in the xxxth yere of the Raigne of our Soveraigne Ladie// Elizabeth by the grace of god Queene of England Fraunce and Ireland defender of the Faithe ec. witnesseth that// Thomas Elliot the yonger the Sonne of Thomas Elliot thelder of the Cittie of New Sarum in the Cowntie of Wiltes// Tayler hath put himselfe Apprentice to and wth the said Thomas Elliot thelder his father of the Cittie and Cowntie aforesaide// Tayler wth hime to dwell frome the daie of the date hereof unto thende of Terme of Seaven yeres from thence for the// next ensuige and fullie to be completed and endid for by and duringe all wch saide Terme the saide Thomas Elliot Apprentice// the said Thomas Elliot as his Maister well and faithefullie shall serve his secretes shall kepe, his comaundments lawfull//and honest… where shall doe no fornication in the howse of his saide Maister or elsewhere he shall comite hurte to his same// Maister hee shall none doe or suffer to be done but hee to his power shall it lett or his saide Maister thereof forthewiuthe warne and// gerve to understande. Taverns he shall not haunt, The goodes of his saide Maister inordinatlie he shall not wast nor them to anie// man lende wthout his Maister's license Matrymonye within the saide Terme he shall not contracte, nor himself to any// woman espouse frome the service of his said Maister by daie or night himself he shall not absent but as a trewe and// faithefull Servant orght to behave himselfe so shall he bear and behave hime selfe towards his said Maister ans well in/ Worde as Deed And the saide Thomas Elliot thelder the said Thomas Elliot theyounger his apprentise in the arte// and misterie wch he nowe usethe after the best manner that he can or maye shall teache and informe or cause to be//taught and informed as mutche as to the said arte and misterie belongeth or in any wise appertayneth with//reasonable chastisement and correction findinge his said Apprentice by all the tyme aforesaid houlsome and// sufficient meat and drink lodginge lynnen wollen hose and shoes and all other things meet and necessarye for an Apprentice// 155 of such a science to be found and alowed after the manner and custome of the said cittie of New Sarum. And further// to his saide Apprentice in thend of the same yeres doubbell apparell meet and convenyent for him to weare and three shillings// and fowerpence of Lawfull money shall geve and delyver. In witnes whereof the parties aforesaid to these indentures// interchangeablie have sette their hande and seales the daie and yere first above written. Signed Sealid and deliverid in// the presence of Thomas Murivall// Thomas Willis// Jo: Symons// By me Thomas Elliott.

Land lease contracts

In medieval times, contracts were also used when landowners leased their land to others to manage and work. These agreements usually required the tenant to pay rent or tax to the landowner.

A lease by indenture

This example is a lease by indenture dated 20 May 1553, between:

- Robert Howlesse, a draper (a seller of fabric or clothing), and

- Henry Burge, a carrier (a transporter of goods or provisions).

The lease was for a period of 26 years, beginning on the Feast of the Nativity of St John the Baptist (24 June 1553) and ending in 1579.

Rent was to be paid 4 times a year, on the following feast days:

- Michaelmas – 29 September

- Christmas – 25 December

- Lady Day (Feast of the Annunciation) – 25 March

- Midsummer (Nativity of St John the Baptist) – 24 June

The contract states:

All that his messuage or tenement with all Stables, Sellers, Sollers, Chambers, Romes, Edyfices & buyldynges to the same messuage or tenement belonging with all & Synglar thappurtenances set lying and beying yn the Citye of New Sarum afforesaid yn the countye afforesaid yn the north syde of a Strete there called Chypperland Strete between a tenement of the said Robert Howlesse on the East partye & garden in the tenure of John Plather on the west partye & tenement of John Eyer and the said Strete on the South parte.

Term:

From the feast of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist next after the date hereof for the term of twenty-six years.

Rent:

Yielding sixteen shillings at the four usual feasts, namely Michaelmas, Christmas, Ladyday and Midsummer in four equal parts.

Learning activities

Activity 1: Spelling by sound

Spelling a word by how it sounds can help—but it doesn’t always match the correct spelling. For example, “phone” might be spelled “fown” if written purely by sound.

- Ask students if they’ve ever been told to “sound it out” when spelling a word. Did it help?

- Write a short passage using common words familiar to the class. Include a few unfamiliar or complex words.

- Read the passage aloud slowly while students write what they hear.

- Ask them to cover their work.

- Read the same passage two more times, using a different speaking style each time—change your tone, stress different syllables, or pronounce some words slightly differently.

- Have students compare all three versions of their writing.

- Did their spelling change based on how you spoke?

- What did they learn from that?

- Ask students to compare their writing with a classmate’s.

- How did their spellings differ?

- Discuss how this reflects the inconsistent spelling seen in historical documents.

Activity 2: Read a historical document

Spelling and writing styles have changed over time. Explore how people wrote in the past and how we can still understand it today.

- Provide students with a short section from the contract of Thomas Elliot the younger, written in its original form (check the content for age-appropriateness).

- Ask students to read the text aloud, sounding out words as they are written.

- Discuss:

- Can they understand what the document says?

- Can they identify modern equivalents of older spellings?

Activity 3: What evidence do we leave behind?

In the past, people left behind letters, contracts and diaries. Today, most of our communication is digital.

- Conduct a class survey:

- What kinds of documents or records do we create today?

- Think about texts, emails, social media, online searches and photos.

- Ask students to reflect on:

- What might future historians learn about us from these digital records?

- What do they share online without thinking?

- Introduce students to how the Australian legal system defines documentary evidence and electronic communications.

- Discuss what kinds of digital content could be used as evidence in court.

- Ask students to reflect on their own electronic footprint.

- What does it say about them?

- How might it be used or misunderstood in the future?