Personalities

About the principals

It was Ashton, Fullwood, Mahony and their fellow artist–illustrators who created the images most often seen by Australians. Their work led art historian Bernard Smith to describe Australia in 1945 as ‘one of the most important centres of black-and-white art in the world’ (Place, Taste and Tradition).

Although many Australian artists contributed to the Atlas — including William Macleod, Constance Roth, Ellis Rowan, W.C. Piguenit, Livingston Hopkins and George Ashton — the publication was largely produced by American artists, cartographers, engravers, printers and canvassers. This collaboration between American and British–Australian talent led The Freeman’s Journal in 1886 to call the Atlas ‘the birth of Art … beneath the Southern Cross’.

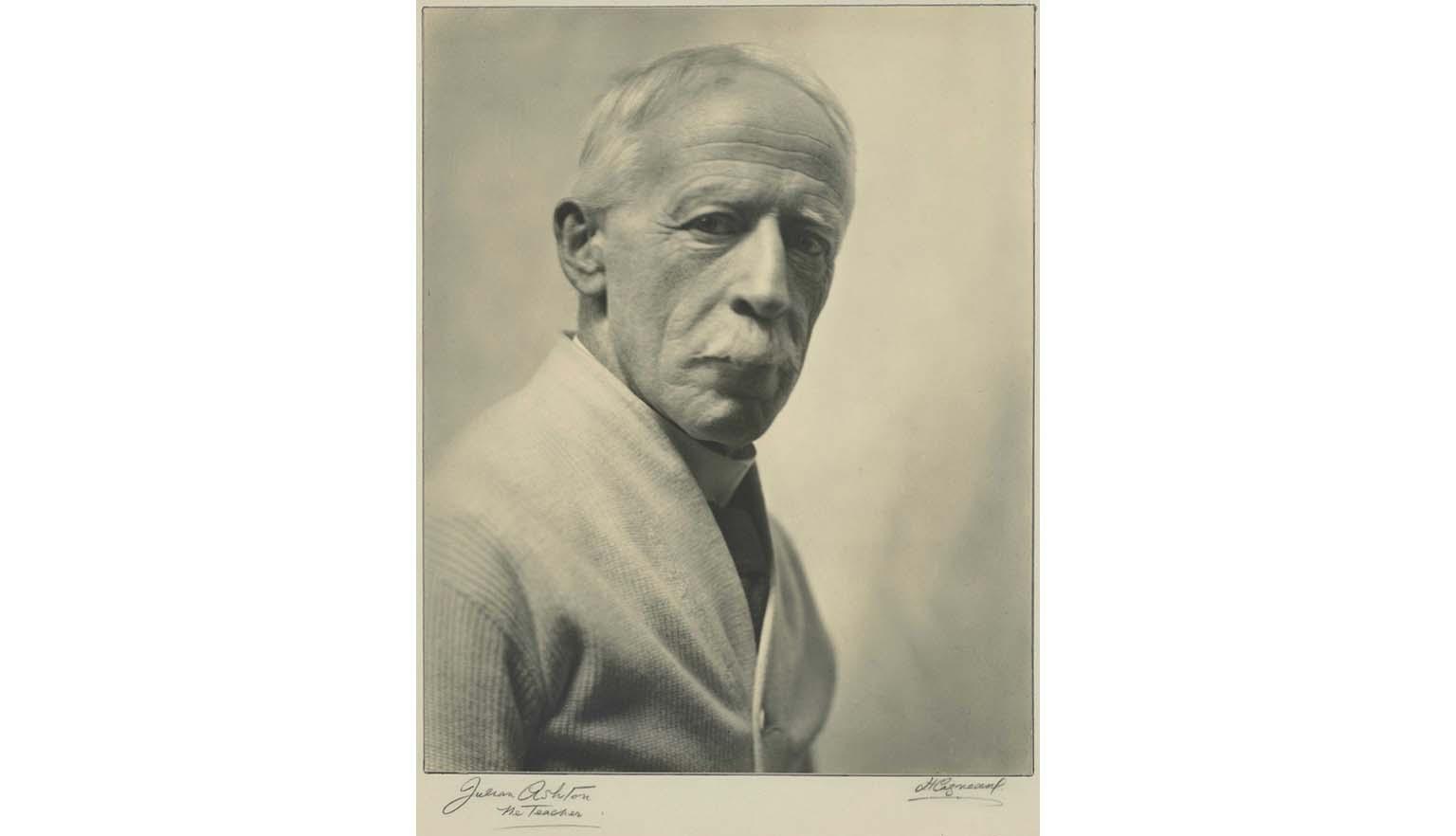

Julian Ashton, the father of Australian art

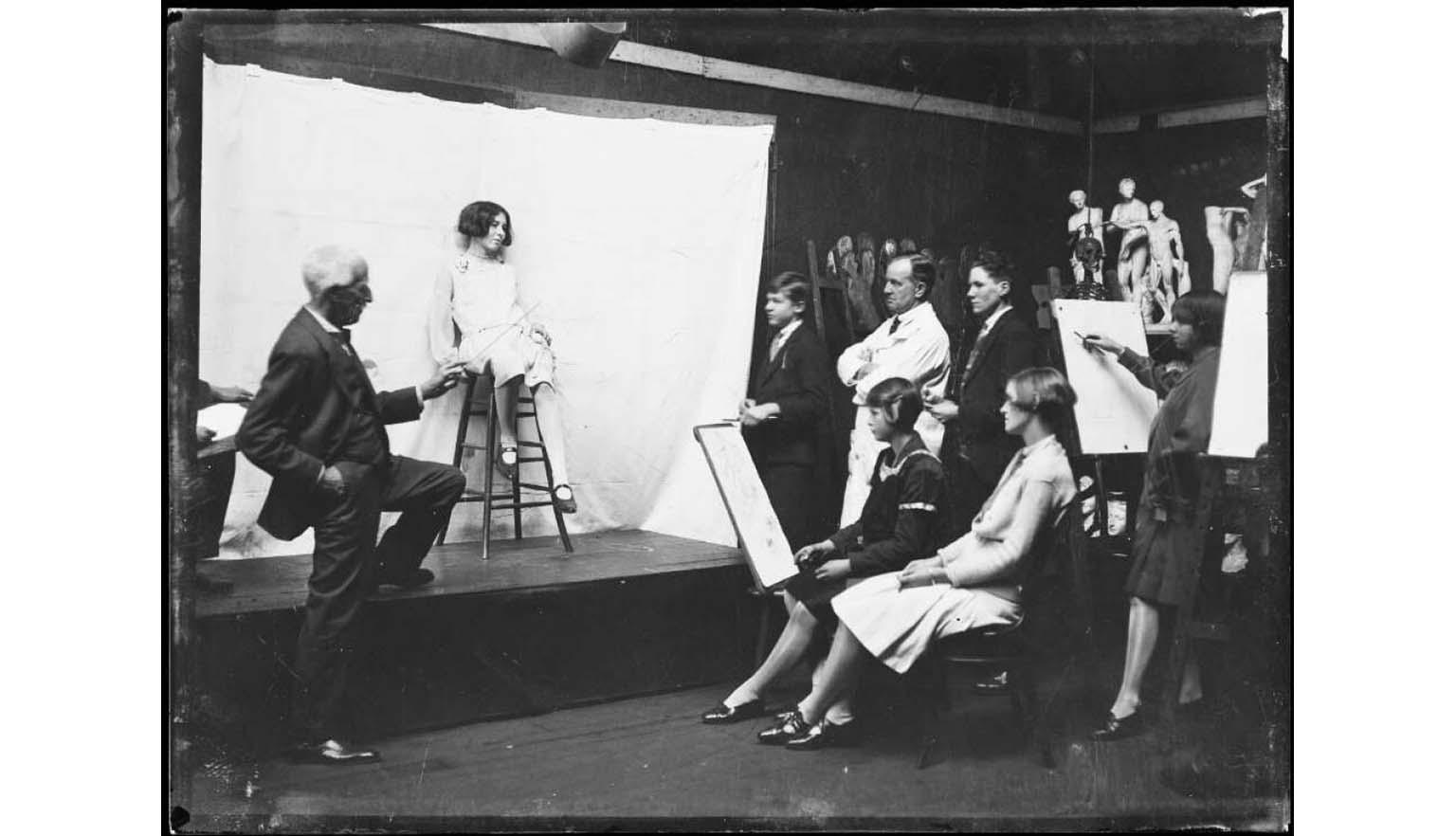

Julian Ashton wanted to form a school of Australian artists who would draw inspiration from the land in which they lived.

As president of the Art Society of New South Wales and a trustee of the National Art Gallery of New South Wales, Ashton persuaded the government to provide £500 each year to purchase works by Australia’s settler colonial artists.

In 1895, he established his own art school. He taught students who later became well-known artists, including George Lambert, Sydney Long, Grace Crowley and Thea Proctor.

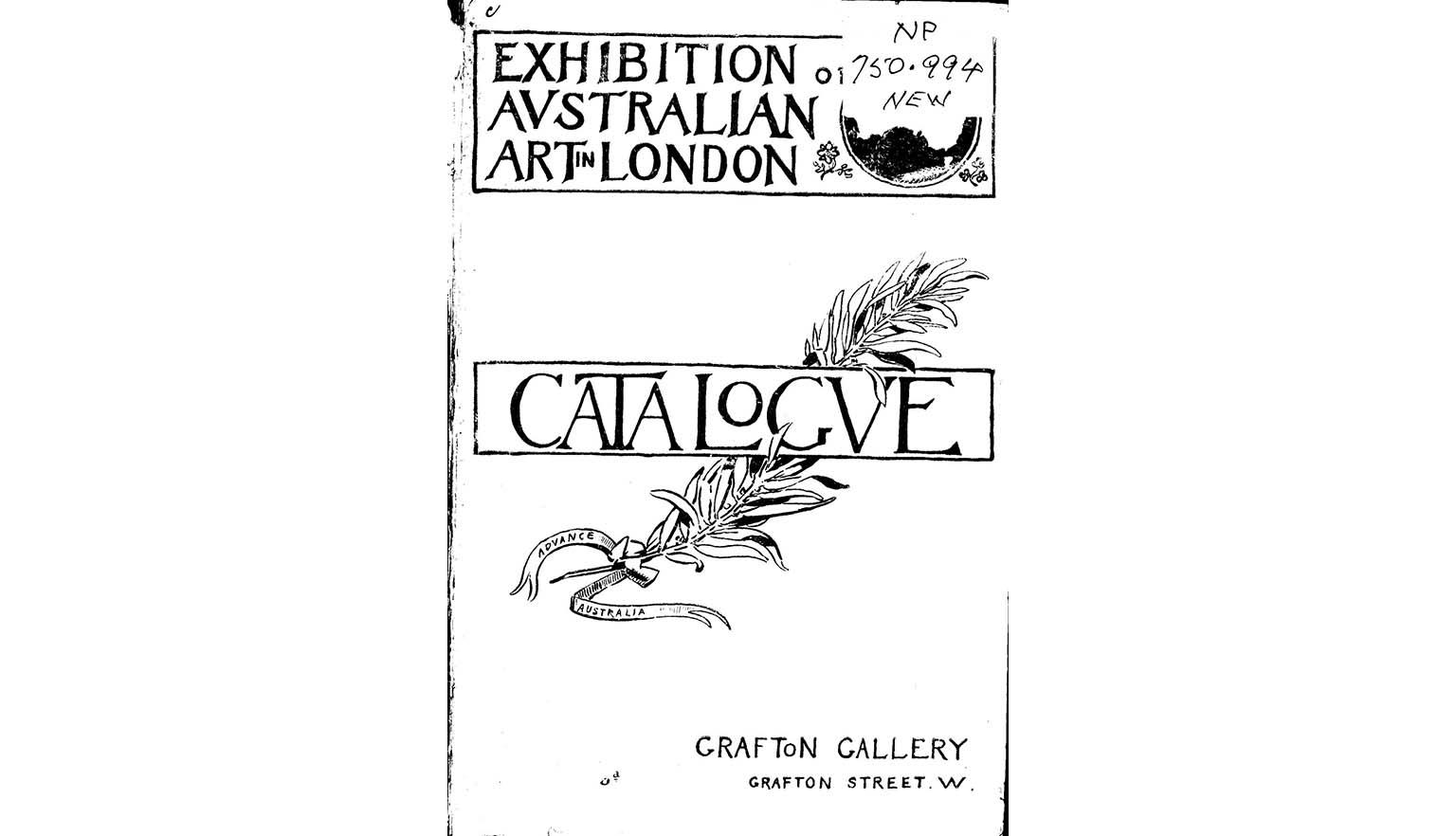

Ashton helped promote Australian art internationally. He exhibited works at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago and the 1898 Exhibition of Australian Art in London. These included drawings and engravings from the Atlas, as well as works by Ashton, Fullwood and Mahony.

Today, Ashton is better known as ‘the father of Australian art’ than for his own paintings.

Albert Henry Fullwood, a Sydney impressionist

Albert Henry Fullwood became the principal artist at The Sydney Mail. He was also a successful impressionist painter and a strong advocate for the rights of professional artists.

A collapse in the Australian art market forced Fullwood to move to London, where he had limited success. He later returned to prominence as one of Australia’s official war artists during the First World War.

The Art of Henry Fullwood (18 September 1927), The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW : 1883 - 1930), p. 22. nla.gov.au/nla.news-article247925885

The Art of Henry Fullwood (18 September 1927), The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW : 1883 - 1930), p. 22. nla.gov.au/nla.news-article247925885

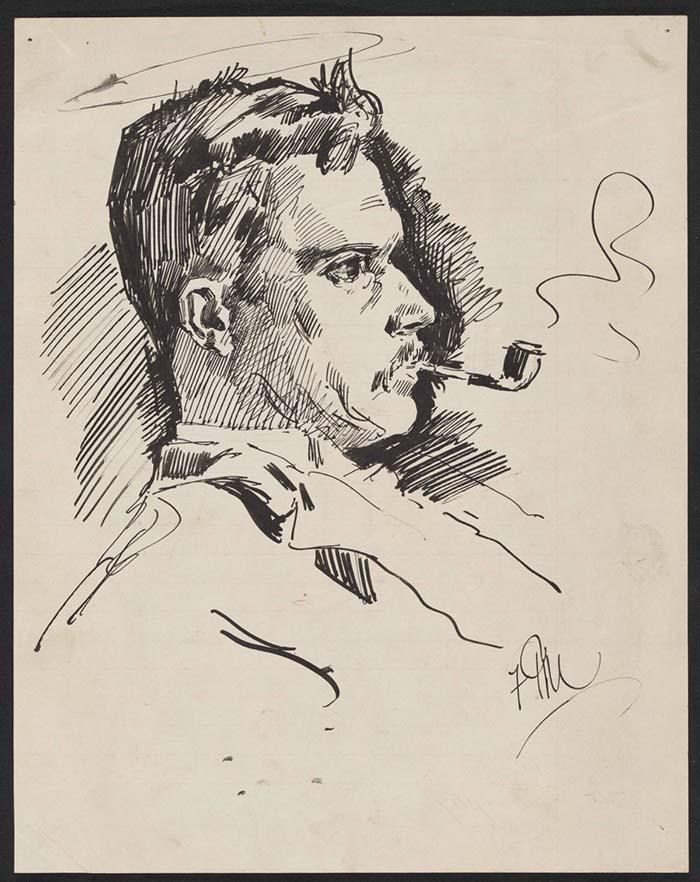

Frank Mahony, our man at The Bulletin

Australian-born and trained, Frank Mahony was already recognised by The Illustrated Sydney News in 1889 as someone on whom ‘Australia … depends for artistic name and fame’.

His success with the Atlas led to regular work with The Bulletin. His cartoons of bush life reflected the rough humour — often racist and misogynist — of what became known as the ‘bushman’s bible’. His illustrations for works by Henry Lawson, ‘Banjo’ Paterson and Steele Rudd helped define The Legend of the Nineties.

Mahony is best remembered for his paintings of livestock, bushrangers and stockmen.

Frank Mahony, [Self-portrait] [picture] / F.P.M., 1900, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136050024

Frank Mahony, [Self-portrait] [picture] / F.P.M., 1900, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136050024

Learning activities

Activity 1: Influential school

Have students investigate the history of the Julian Ashton Art School, and its alumni. Why has it produced so many successful Australian artists? As a starting point, search Trove.

For example, you might allocate an artist who attended the School to each student for a short research task. They should briefly outline the artist’s association with the School, and their career highlights following.

Activity 2: Fullwood’s landscapes

We hold a collection of 34 landscape oils attributed to Fullwood, painted around 1904.

- Assign one painting to each student for analysis and annotation.

- Students should identify features of the Australian impressionist or Heidelberg style and reflect on any influence the work may have had on their own artmaking.

- Present findings in a slideshow.

Activity 3: Our man at The Bulletin

Frank Mahony contributed artwork to the publication from the 1890s. Have students use the Trove Digital Library viewer to locate examples of his work in the full digitised set of issues of The Bulletin.

Watch our The Best of The Bulletin Cartoonists video (2019), where Dr Guy Hansen discusses cartooning in The Bulletin. At [17:45], he talks about ‘gag cartoons’ — short, humorous sketches often drawn by Mahony.

After watching the video or listening to the audio (linked below), have students:

- Create their own ‘gag cartoon’ in the style of Mahony and The Bulletin.

- Write a very short humorous conversation between two characters and

- Swap it with a classmate to illustrate, mirroring the process at the late nineteenth-century serial.

Best of the Bulletin - Dr Guy Hansen

*Speakers: Stuart Baines (S), Dr Guy Hansen (G)

*Audience: (A)

*Location: National Library of Australia

*Date: 12/7/2019

S: Welcome to the National Library. I'm Stuart Baines, Acting Director of Community Outreach Branch here at the Library. As we begin I would like to acknowledge and celebrate the first Australians on whose traditional lands we meet. I pay my respects to the elders of the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people past and present for caring for this land we are now privileged to call our home.

I myself grew up on the lands of the Awabikal people and was in a position to attend a primary school where they recognised and valued the first nations people and exposed us to their culture. I've now lived and worked for many years on the land for the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people. I am proud to be part of a national institution that plays a part in sharing the collections, cultures and languages of indigenous Australians through its events and education programs.

It's my pleasure today to welcome you all to the Library. For today's event we are here to celebrate the exhibition, Inked: Australian Cartoons which will close its doors next Sunday so I hope if you haven't visited yet that you'll visit today after we've finished, after Guy has inspired you and if you have already visited visit again.

Inked features a selection of the best cartoons from the National Library of Australia's extensive collection. Drawing from over 14,000 cartoons the exhibition is curated by Dr Guy Hansen who is also Director of Exhibitions here at the Library.

Today Guy's lecture will provide a short history of Australian cartooning from The Bulletin and investigating the emergence of cartoonists as serious social commentators of the 20th century. Please join me in welcoming Dr Guy Hansen.

Applause

G: Thanks very much, Stuart, for the introduction. As Stuart said I am looking specifically at The Bulletin today and that is a subset of the cartoons which are on display upstairs. We go far beyond The Bulletin upstairs but there is a – in the early section of the exhibition there's some lovely examples of Bulletin cartoons in there.

So The Bulletin is perhaps one of the most famous periodicals in Australian print history so I'll put up a cover for you, I think. There we go. That might be the sort of thing you think of when you think of The Bulletin. This weekly magazine was produced from 1880 to 2008. Sometimes known as The Bushman's Bible it quickly established a reputation as a national publication, prided itself on presenting the very best of Australian cartooning and writing.

While it was based in Sydney it always sought to transcend the parochial interests of New South Wales and articulate a unique Australian view of domestic and international events.

Reading The Bulletin from the 1880s is both familiar and strange at the same time. It's like looking through an old family photo album. You recognise many of the people and events depicted. They relate to stories that you've heard from family and friends. Many more of the images however relate to events and personalities long forgotten. Looking at these images raises as many questions as it answers.

Commentators writing about The Bulletin often point to it's important as a nursery for Australian black and white art. In particular the period dating from the 1880s through to the first world war is often seen as the golden age of Australian cartooning. For some this argument is taken even further to suggest that The Bulletin of this period produced some of the best cartoonists in the world.

This is one of those statements often asserted but rarely tested. Very few people today have actually gone back and looked in detail at The Bulletin and its cartoons. Today I'm going to take you on a guided tour of The Bulletin during its golden age and draw some modest conclusions about the significance of this periodical.

To give some structure to this story I'm going to concentrate on some of the key artists who were published in the magazine at this time. I'm going to look at Livingston Hopkins or Hop as he was known, Phil May, Norman Lindsay, B E Minns, David Souter and David Low. This is just a small number of the hundreds of cartoonists who worked for The Bulletin in the lead-up to the first world war. The Library is very lucky to hold examples of original artwork by all of these artists and some of the best of them are on display in the exhibition upstairs.

Before jumping into this story of The Bulletin's star cartoonists I need to do a short advertisement for Trove. Some of you will be aware that The Bulletin is now digitised and available at your desktop. The digital humanities scholar, Tim Sherratt, who's at University of Canberra, has written some very clever code which tracks down Bulletin cartoons from the digital archive and presents them in a very digestible fashion. Tim's cartooning guide allows you to see the Bulletin's title page cartoons in isolation while also giving you the opportunity to dive back into The Bulletin to see it in its original context. This does not capture all of the cartoons in The Bulletin but it does point to some of the most important ones.

Previously this kind of research would have taken months but now thanks to Tim's shortcut can be done in a matter of days. So literally I looked at something like 4,000 cartoons in preparation for this paper and I was just able to quickly do this clicking through copies of The Bulletin. So traditionally what I would have done is sat in the reading room and called up the bound volumes of The Bulletin and slowly flicked my way through but now I can do it very efficiently at my desk. I have to thank Tim for this but I also have to admit that I miss the older, more leisurely type of research.

One more thing that I need to do before beginning our guided tour of The Bulletin is to provide a warning that some of the images that I'm going to show are by today's standards offensive. Many of them are quite explicitly racist. While I'll be discussing these images in their historical context I'm very much aware they can be deeply offensive to a modern audience. Indeed some of the images I would argue were deeply offensive at the time that they were drawn. My aim in showing these images is not just to stand in judgement of the past nor to generate a gratuitous shock but rather to provide a clear-eyed assessment of what The Bulletin was like. Exploring how Australian cartoonists depicted Asians and Aborigines is still very relevant today. You cannot look at these cartoons without recognising that racism is very deep in the DNA of modern Australia.

So let's begin our tour of The Bulletin. As I mentioned before The Bulletin was established in 1880. Its founding editors were John Feltham Archibald and John Hayes. It quickly grew to be one of the major magazines distributed throughout the colonies. At this time there were approximately 600 newspapers and magazines being produced in Australia. These include country papers, town papers, suburban papers, metropolitan dailies and metropolitan weeklies. Many of these publications were short-lived or had a limited audience. The Bulletin however was different, it would last for over 100 years and develop an audience across Australia both in the cities and in the bush.

I think it's important to remember that this was a period in which Australians were voracious consumers of print media. High levels of literacy and the beginnings of gas light and electricity meant that reading was the main leisure activity for the population. This is long before there's competition from radio and television. Richard Twopeny, a well known commentator, described Australia of the 1880s as the land of newspapers. Print was king. When I think about this period I think of it as peak reading in Australian history.

In terms of cartooning it's important to remember that at the time The Bulletin was established photographs were not a major feature of magazines and newspapers. Daily newspapers did not for the most part feature illustration. The weeklies however did often have drawings and illustrations. It wouldn't be until the late 1890s that photos started regularly appearing.

So to kind of – you're looking at a period where there's no photographs and it's really only the weekly magazines which can have these more lavish illustrations and that's to do with the production processes required. Later on of course illustration, both photographically and black and white art would become an increasing part of newspapers and magazines.

So let's go back a little bit before The Bulletin, I want to give a little bit of a history before The Bulletin so we can go back to Punch. Now Punch was a precursor of The Bulletin and had started in England in the 1840s. Punch was good at echoing the tradition of political satires and prints that had been popular during the Georgian era. If you go up to the exhibition you'll see some of these earlier Georgian satires. Punch was heavily illustrated and it was in fact Punch that popularised the term, cartoon, as a descriptor for satirical drawings and caricatures.

The word originally referred – it's an Italian word and it originally referred to large drawings which were usually done on paper on a wall in preparation for a mural. It was in 1843 that part of the British Houses of Parliament, they were preparing a mural on a wall and these large cartoon paper drawings had been prepared, a very worthy – subjects for that mural. It was at that time that the Punch artist, John Leech, gleefully appropriated the term, mural, from the British Parliament and those drawings to refer to his own drawings. It was of course a joke because his drawings were in no way serious but the term cartoon stuck and it's of course come – people rarely know what it was originally for and it's now become the popular term for these sorts of drawings.

Inspired by the early tradition of satirical prints or caricatures Punch included black and white print in each issue, almost like a little removable centrefold or poster. Punch's prints were much simpler than the earlier Georgian satires. Rather than numerous characters and extended talk balloons the new prints featured only a small number of characters with little text. Limited edition hand-coloured engraving typical of Georgian satires had been replaced by the black and white wood block prints which were produced as a supplement inside the magazine. This new style of cartoon foreshadowed what cartoons would be coming in 20th century.

Punch quickly grew to be one of the most successful humorous magazines of the 19th century. Versions of this magazine could be seen all across the world and in the Australian context there was a Melbourne Punch, a Sydney Punch and I think there was also an Adelaide Punch. So this is sort of a successful business model which exists prior to The Bulletin.

Another important precursor to The Bulletin were selections of print drawings which were sold. One of the most famous of those was those produced by S T Gill and here you can see the cover of one of his collections of humorous drawings of Australia.

Now S T Gill was originally from England, he'd come out to Australia and following the discoveries of gold in Ballarat and Bendigo he made his way to the goldfields and over the next 20 years he published several collections of drawings of life on the goldfields. These were often humorous drawings and picked up on the nice little things which are happening on the goldfields. Some of you might have seen the S T Gill exhibition we had a couple of years ago.

So I just want to get this idea across that you have Punch and you have things like S T Gill had already established that there was an appetite for humorous drawings about Australian culture. Just one example which I have in the exhibition of S T Gill is this lovely drawing of some miners celebrating. They've gone back to Melbourne and they're spending their hard-earned gains drinking the establishment.

So I like to think there's a direct line between Punch and S T Gill in The Bulletin. The founders of The Bulletin wanted to take the elements that Punch and Gill had already demonstrated and use them in a national magazine about Australia.

So The Bulletin formula as such was to have the best writing and the best cartooning available all delivered in the distinctly Australian voice. So it's very ambitious at this time in the 1880s to produce something which would be for all across Australia 'cause we're still in the period of the colonies.

Before I get into the detailed story of the cartoonists I just want to dip my lid to the writers of The Bulletin 'cause indeed it's most probably the writers who are even more famous than the cartoonists and in particular Henry Lawson and Banjo Paterson. They were a very important part of the stable of writers and poets who worked on The Bulletin and helped make it so successful and sometimes the writers came together with the cartoonists and I just include this slide here. Christmas edition of The Bulletin's always a nice one to look at and you can see The Man from Ironbark with the illustrations done as well. So I don't want you in any way to think that I'm forgetting about the writers, it's just not the subject of today's talk.

So returning to the story of how cartooning developed at The Bulletin we can look at the first edition of the magazine in 1880 and we can see a different sort of magazine. It is at this point quite staid so they've just opened, they're still using the traditional wood block technology, it looks very much like many other weekly newspapers at this period, hasn't developed a kind of style that it would later so it wasn't a little bit until the mid-1880s that The Bulletin started to become what we'd think of today as this sort of full of cartoons.

So some of the changes was in 1883 The Bulletin started having the red cover and I've actually brought a Bulletin along here so you can see – it is nice just to see what the old-fashioned Bulletin used to look like and you can also see that a main feature of The Bulletin was the use of - the front page was very much used for advertising and it would often be a couple of pages in before you actually got to the front page of the actual magazine. So I think we forget what these papers used to look like.

So moving from about the mid-1880s let me sort of step you through what The Bulletin was like and how it used cartoons. So The Bulletin would often feature – well nearly in every edition from this, from the mid-1880s onwards have a cover page which was a couple of pages inside the red cover and would be the real cover page. They used their star cartoonists to always illustrate full panel cartoon on this cover and this is what Tim Sherratt's software is so good at finding is these cartoons. Here you can see a classic caricature of Henry Parkes by Livingston Hopkins.

So another aspect of The Bulletin in this period all the way up to world war one was what they called [cartoonlets] 15:22 and these would be kind of like the illustrated news where the writing would be giving you a story from the week 'cause it's a weekly so you're catching up with the events and the artist would do these little tiny humorous drawings of what had happened. That was a big – a constant feature of The Bulletin up until world war one.

It would also often have these supplements or posters which you could remove and they would often be quite a strong, powerful illustration or cartoon. This one of course is a world war one cartoon and it's pretty much a – you can see the German hordes descending on the wounded Australian soldiers and it's a bit of a plea for Australians to recruit, The Bulletin being quite a patriotic paper.

Of course the other aspect of The Bulletin's cartoons were these smaller cartoons which were inserted throughout the newspaper and would often be illustrating to humorous stories or would just have a straight gag so gag cartoons was very common. Somebody would write the gag and then the artist would be asked to just do an illustration.

Now this one here, you most probably can't read it and I'm actually having trouble reading it here but I'll just magnify it so I can just go back and I'll read out the punch line just on one to give you a sense of – it says in the cow country, first cocky. Herd's had terrible bad luck, ain't he? Had a couple of his cows drowned, I hear. Second cocky. Ain't a couple of his cows, it's a couple of his youngsters. First cocky. Oh is that right, is it? Wonderful how rumour exaggerates things, isn't it? So fairly grim colonial sense of humour and you also see here the archetype of the bushie, the big beard so as you went through the – this is a Norman Lindsay – as you went through The Bulletin you'd see these archetypes, characters. It'd be the new chum, the migrant from England or you'd see the bushie and these things and they became really part of the visual vocabulary of The Bulletin.

So there's the sorts of cartoons you'd see, these big editorial cartoons but also these little illustrations often related to some story or theme in the paper. So hopefully I can get back to normal now.

So let me also give you a sense of the editorial line of – I should say the other thing about The Bulletin too if you go back and read it, it's actually quite hard to read 'cause of the way people wrote in the 1800s like a Henry Lawson or Banjo Paterson, that's great but there's actually long editorials, very argumentative, quite florid use of language. It's quite a strange experience reading The Bulletin from this period so if you want to transport yourself to a different time go back and read some of the longer articles and see what you think.

But let me – I won't read out great chunks of The Bulletin to you but I will summarise its editorial line from this period. Here I've just taken the masthead and I just want to emphasise Australia for the white man. That was the slogan on The Bulletin for a very long time, right up until – initially in the 1880s it was Australians for Australians which of course related to the idea of a push for federation and then of course coming into federation it switched over to Australia for the white man which was very much an expression of the white Australia policy. It went all the way until the 1960s with - that slogan stayed on the masthead and then Donald Horne came in and removed it when he became editor of The Bulletin. So it sort of gives you a sense of the way The Bulletin saw the world.

But other major features of the editorial policy of The Bulletin I'll capture now and I'll do that by – I'll illustrate that with cartoons. So here white Australia I just mentioned is on the thing and of course the cartoonists often would draw cartoons specifically extolling the virtues. You can see Edmund Barton here sort of arguing with John Ball about the benefits of white Australia. Of course the Colonial Office did not like the white Australia policy but of course the white Australia policy was very popular in Australia.

The Bulletin was also during this period consistently anti-imperialist and you can see here that you have the English characters trying to persuade the young Australia what to do and the caption down the bottom reads, 'the price of imperialism'. So there was this radical nationalist line in The Bulletin and at times The Bulletin was very much pro a republic and really separating itself from the idea of a – imperial Commonwealth. I mentioned The Bulletin was very pro-federation so you'll find a lot of editorial and cartoons promoting the benefits of Australia and here you have a nice federation kangaroo crossing over the Murray River here helping to unite Australia.

Another thing about The Bulletin was it was very – for most of its time it was very pro-protectionist and it believed in a tariff war so Australia could develop its own industries. Going back to before the existence of the Liberal Party and even before the Labor Party the big political split in Australia was often between free traders and protectionists and The Bulletin very much firmly came down on the protectionists' side of that debate. So that gives you a sense in the context which cartoonists were working in The Bulletin in this so-called golden age.

So I can now turn to some of the cartoonists who are in our collection and are featured in the exhibition. The first one is Livingston Hopkins or Hop and he I think is perhaps the most interesting 'cause he's there from the mid-1880s or early 1880s all the way through until world war one so following Hop you can pretty much see the whole story.

Despite my comments about The Bulletin's ambition for it to be the best of Australian cartooning the editors soon decided that there weren't really people in Australia who could do what was required and they went seeking talent overseas and so they went to America and recruited Hop. Hop had actually fought in the civil war and he was working in New York as a cartoonist for a New York periodical and W T Traill who was the then editor approached him and persuaded him to come over to Australia, offered him a very good living if he'd come to Australia. So he uprooted himself and came over to Sydney.

So you can see here the character carrying the club with Bulletin written on it that's actually a caricature of Hop himself and you can sort of see his attitude to cartooning. He very much saw himself as almost like a hired thug for The Bulletin who would ruthlessly crack the heads of politicians with satirical cartoons so it's a lovely illustration. But his fame was such that he could actually put himself in the cartoons as well.

The thing – one of the advantages that Hop had was there had been a change in technology in printing so The Bulletin had no presses which had photo engraving unlike the old wood block printing process – I showed you earlier an example of that - and Hopkins was able to use this technology much better. You can see how much more lively his drawings are compared to that drawing which was on the first edition of The Bulletin.

This one here you can see he's done a drawing of Edmund Barton and he's holding the newly delivered baby of the Commonwealth there. That's the little baby Australia there. Just as another kind of lovely little illustration of Hop which sort of shows how his type of drawing really freed up how artists could express themselves. Those old wood block prints are very stiff, you start to see much more expressive drawing is in this period. This one here, given we've just got the World Cup Cricket on, I've selected and the caption reads, 'the big scrub team played to see which of them shall be emergency man in the final Australia versus England test match'. So you can see some kids in the country enjoying their cricket.

Okay so Hop – and some of you may have heard me tell this story before but it's such an important story I feel I need to tell it again – Hop is famous for inventing the little boy from Manly and the little boy from Manly, this is the first time he appears in a cartoon and you can see him here. At this stage he's not called the little boy from Manly, he's called the little boy at Manly. The story here is, this cartoon was done on – it was done in 1885 on the occasion of New South Wales deciding to send a contingent to the Sudan in an expression of patriotic and imperial fervour and this was following General Gorton being killed at Khartoum. The response to that was a range of expeditions went over to basically give retribution, revenge for that event and some New South Wales troops went. They didn't see a lot of action and The Bulletin with its anti-imperialist position was very sceptical about whether New South Wales should be involved in this and hence when the New South Wales troops returned this cartoon satirised that event.

I got a little bit of explanation to understand – this is the challenge of cartoons, is you've got to know a lot to understand what's going on in the cartoon and the reason why he's got a little boy is at this time when the troops had left for Africa there had been a little boy who'd written a letter to the Premier of New South Wales. The Premier at this stage was [Daly] 25:54 and in the letter he said how proud he was of seeing the contingent going out through the heads and this letter had been reproduced and helped raise funds for the New South Wales contingent. So the little boy from Manly was seen as this sort of patriotic figure and become a talking point in Sydney at the time.

So Hop has deployed the little boy here playing his little drum and the New South Wales contingent comes back and you can see here they are here and Hop is making reference to a work called the roll call which is a very famous patriotic work which was well known. There was a copy of this painting on display at the New South Wales Art Gallery at this time and in this painting you can see some Crimea – some British troops at Crimea after a battle badly injured but being nobly led and heroically doing their job as soldiers so this is quite a patriotic and noble depiction of service in the imperial cause. Of course that's juxtaposed with Hop's where he's borrowed the major elements of the painting, the officer is now [Daly] but instead of riding a noble war steed he's got an old nag. He's got a bunch of medals on his lap which he's going to hand out. You can see that the worst injury we can see here is a sore tooth so it's quite a satire of imperialism.

Now this idea of the little boy representing Australia really took off and became a feature of Australian cartooning right up until world war two and here you can see Hop using the little boy from Manly again in a later cartoon and in this time he's using the idea of the size of the debt which is a small ball in 1866. You can see by 1906 the size of the debt has become much, much bigger. You can also see the anti-semitic line of The Bulletin with the depiction of the moon here in the end so there's some of these deep ideas at play in The Bulletin and in Hop's work.

Here is another cartoon which I really like which shows the little boy from Manly here standing in front of Hop, Hop is at his easel and the little boy is concerned that Hop's no longer going to draw him because federation has come but Hop is reassuring him that yes, he thinks he needs the little boy for a little bit longer yet. Of course he did 'cause the little boy did continue to appear in cartoons, not only by Hop but by many artists for some years.

Now all of those cartoons illustrated how Hop would regularly just illustrate the editorial line of The Bulletin and really prosecute the kind of the argument which the editors of The Bulletin wanted prosecuted. Another aspect of that was fear of the Japanese and in this cartoon, quite a racist cartoon, you can see Japanese nation is depicted as a monkey and it's on top of a bear and this of course is in 1905 not long after the Japanese had defeated the Russians which was a great surprise to the western powers that Russia could be defeated by the Japanese. The monkey's saying now that my hand is in, shall I go to Manila for some eagle shooting or to Australia for a kangaroo drive? Both very good sport, I should think. So you're seeing The Bulletin wanted to prosecute this argument that we had to be scared of the Japanese.

I thought just as my final – example of Hop – he's getting quite an old man by this stage and his work's not as good as it was earlier but I thought this is nice to show a Canberra audience because it depicts the federal capital site, Canberra – the ACT, basically. Hop's a bit dubious about the site and Santa Claus is flying over in 1912 and he says what, no chimneys to put toys in? No houses? No children? No nothing? We'll try again in another 10 years so Santa Claus at the federal capital.

So that's a few cartoons from Hop. Let me move now to another one of The Bulletin stars, Phil May. Like Hop before him May was also recruited from overseas by William Traill. May who was working in London at the time had achieved some notoriety as an illustrator but was still struggling to establish a career. The offer to join The Bulletin gave him the chance to develop his talents which would allow him to return to England later as a major cartooning talent.

In fact it's really quite weird, you often see things that - people think that May is an Australian and is an example of one of the very successful Australian cartoonists who has gone overseas and proved how good they were but he was actually English, came to Australia and went back. Some of the other Australian cartooning stars as it turns out are not actually Australian, Hop being another one.

The Bulletin used May's extraordinary graphic skills to bolster its editorial commentary. May proved to be an effective propagandist just like Hop and was able to develop the perfect visual metaphor to drive home The Bulletin's message. Which brings me to – well there's an example of Phil May and you can see Phil May was actually even a better draughtsman than Hop and his caricatures and his line work were just amazing and it really set the standard. I think nearly all the artists wanted to approach the quality of line work that Phil May had.

But coming to Phil May as a propagandist this work which you can see in the exhibition, printed in The Bulletin, is the Mongolian octopus cartoon and this comes from the 21st of August edition, 1886 which The Bulletin had devoted to condemning Chinese migration to Australia. It has a series of articles which read like xenophobic rants. Article after article argue that Chinese migrants suppress workers' wages, spread disease and promote gambling and corruption while also encouraging opium use and prostitution. The Bulletin was particularly concerned about the virtue of the colony's young women who robbed of all agency would swoon under the influence of opium.

May's cartoon captures all of these alleged vices in a single drawing. The metaphor of the octopus with its writhing tentacles reaching out to claim its victims is drawn from Victor Hugo's novel, Toilers of the Sea from 1886. Hugo's description of the octopus as a devil fish reflects the fear of sea monsters which loomed large in the 19th century European imagination. In a chapter entitled The Monster Hugo refers to octopuses as devil fish and describes their capacity to kill in bloodcurdling prose.

'No grasp is like the sudden strain of the cephalopod, it is with sucking apparatus that it attacks. The victim is oppressed by a vacuum drawing it at numberless points. It is not a clawing or a biting but an indescribable scarification. So that's fairly powerful political rhetoric there and that's the way The Bulletin was. The Bulletin continued its anti-Chinese policy right up to federation and here's another example by May. A titled cartoon again suggesting the dangers of prostitution and opium. So you can see lots of these sorts of cartoons in The Bulletin if you flick through in the 1890s. May actually left The Bulletin after a fairly short stint and went back first to Paris and then to London in 1890 but he continued to send cartoons for publication. He became very famous for his work in London Punch and became a major cartoonist in England.

So the next artist I want to look at is Norman Lindsay so Lindsay began contributing to The Bulletin in 1901 and he's very well known as a writer and artist in his own right. In some ways that's what he's most probably more remembered for than necessarily his work on The Bulletin but he did work for The Bulletin for about 40 years and was a very consistent cartoonist and illustrator for them.

Again like his predecessors, Hop and May, he was very much a propagandist. When looking at his cartoons you're never left wondering where he stands on an issue, he enthusiastically illustrated The Bulletin's editorial line and in the period after federation this meant he was often on a mission to condemn imperialism and argue for a white Australia. A few examples just to give a sense of his work so this one here is – and I'll just read the caption for you. 'Not wanted.' You have John Ball saying 'ah, I see you've finished with him. Thanks, you can go home, my friends here can do all that is necessary'.

So this is a – interesting cartoon because it's actually about the defeat of the Boers in South Africa – you can see the Boer on the ground there. The Australians of course participated in the war and Lindsay is suggesting it wasn't such a good idea for Australia to get involved and behind – who's behind John Ball? You have basically Chinese and slave labour behind so you begin to see some of the issues of race and anti-imperialism in The Bulletin at this time.

Here is another cartoon from 1905 which is the earliest I found – there most probably are earlier but just in the survey I did recently of Norman Lindsay using the yellow peril so that the caption down here says, 'waking his big brother, the yellow peril to Australia'. So you have like a Japanese admiral who's just defeated the Russian fleet and the concern here is that this leads to a realisation that China will now emerge as a major power so it's sort of looking into the future. So this is this idea of a threat from the north which was very powerful in Australia and indeed still powerful today and you can see that work from Lindsay.

Again on the Japanese question you have all the way right up – indeed right up to world war two you have a constant set of editorials and cartoons of – depicting that Australia isn't taking the threat from Japan seriously. So here you can see the little boy from Manly, he's not wearing his cap on this occasion but he's fallen asleep and you can see a Japanese imperialist military person coming up behind him. So that's the sort of thing that you would see in The Bulletin from Norman Lindsay.

Lindsay – I think some of the most impressive and interesting stuff from Norman Lindsay comes from his work done during the first world war and he particularly liked to use mythic metaphors and gods to depict his story and here you can see the little boy from Manly just hearing the news that the first world war has broken out, looking somewhat confused in the corner and you see the god of war banging his gong above. We're very lucky in the collection to actually have the original of this cartoon as well which has been inscribed by Norman Lindsay and it was done just in 1914 so that's one of the nice things in our collection, we can match up some original works with these – with the publication.

Another work from Norman Lindsay during the war, and you can see here he's deploying his propaganda skills against the Germans rather than the Japanese in this case, and here's a little brief description he has of drawing war cartoons which we actually have an oral history of Norman Lindsay. I must have accidentally knocked it off. We won't worry about that, we'll keep going.

So again more of Lindsay's anti-German cartoons, this depiction of Prussian militarism and the death and destruction of world war one. Counterpoint to this was the square-jawed Australian soldiers who were nobly defending the line. In the background here you can see the slackers who are staying home still playing sport and doing things like that and they need to come to the front line.

So this actual work later became a recruitment poster and here is a cartoon from the very end of the war where you can see – again he's using these mythic – you've got the grim reaper and you've got the devil replete after all the mayhem and massacre they've caused during the first world war. Here's another one of Norman Lindsay's recruitment posters where you can see the German monster. There you can see the original artwork which is in our collection on this side and then on the other side you can see the actual poster. So pretty ferocious stuff.

So I'm going to now move onto another artist, just briefly a couple more artists and then we'll wrap it up. This is B E Minns so he wasn't quite of the rank of some of these other guys that I've been talking but a regular contributor to The Bulletin after federation, very famous watercolourist. He also was English, strangely enough. So few of these guys actually turn out to have come from Australia. Minns, I think – the really interesting thing about Minns was the way he depicted Aboriginal people so The Bulletin was quite affectionate towards - in its depiction of indigenous people but also usually was very patronising and often depicted them as simpletons or figures of fun.

So this is – Minns became very famous for this sort of depiction of Aboriginal people and in some senses when I look at Minns he's a bit of a precursor of that later type of artwork which some of you might be familiar with, the Brownie Downing plates, the ceramic plates which have the illustrations of Aboriginal people. So it is affectionate but deeply racist, deeply patronising. I won't read the joke which is on the joke box here 'cause it is quite racist but that – they would often have these sort of gags where these two characters would say things.

Just as a counterpoint to that I wanted to include this work from Norman Lindsay which shows The Bulletin did have a slightly complex attitude towards indigenous people and there were other cartoons which I could have used to demonstrate this. This is almost like a national museum. I see the figure on the left is almost like a curator here giving a guided tour and here's an indigenous man challenging him and saying, in your story of Australian history where are the Aboriginal people? So you can see the bushranger, you can see the convict, see kangaroo, you can see all these figures but it's kind of like challenging Australia to say well you've left Aboriginal people out of history so I find this a very interesting cartoon from 1912.

I'm going to move to another cartoonist now, David Souter and I've included him because he's the great stylist of The Bulletin, particularly coming into the 20s, lovely art deco-type illustrations so I'll just show you a few examples. So really gorgeous artwork, magnificent artwork and beautiful stuff. Lovely drawings. Now the – I have to tell you they are very sexist so I'll read out the caption on this one. 'But why do you keep calling me Arthur? Didn't I tell you my name was Charlie? Of course, how stupid of me but I keep thinking this is Wednesday.' So yes so The Bulletin was full of a lot of this sort of stuff as well, jokes about married life, about middle-aged men and younger women. Wouldn't past muster these days but it's all there if you want to go back and have a look at it in Trove.

So I will now move to David Low who again, he's a cartoonist often lauded as being an Australian but he's actually a New Zealander and he came from Christchurch in New Zealand, came over to work in The Bulletin just prior to world war one and he broke the mould because all of these other artists we've been talking about have been very willing propagandists. David Low was the first of The Bulletin cartoonists who started saying I'm not really happy with drawing whatever you tell me to draw.

When he first got to The Bulletin he was mainly doing smaller works. He was mainly doing the smaller cartoonlets and things like that but over time he was given permission – here we go, cartoonlets here. You got example of this sort of more minor work inside the paper and he would do that. Over time he got permission to do some of the editorial panels and some of the larger cartoons so here's one of Australians at war and here's another one of Billy Hughes. So the Billy Hughes series is very important because this really makes his reputation as a cartoonist. It's his sort of battle with Billy Hughes and almost like Billy Hughes' nemesis, he's constantly attacking what Billy Hughes is up to and this is a – early front page and this is one from when Hughes was at the peace conference in Paris.

This is the Billy Wog one we just had up before and I'll read this one out. 'Directions for use. Blow up with wind until head expands then release hole in face whereupon Billy will emit loud noises until he goes flat.' Which of course is how Low saw Billy Hughes, was that he was a very sort of – constantly promoting war and very – the way he was prosecuting the peace process, the retribution on the Germans and Low thought that was a bad thing.

There was a story – well all of Low's anti-Hughes cartoons were so popular that he actually was able to produce a book which was – sold 60,000 copies which was one of the bestselling cartoon books ever produced in Australia. It was this book which actually drew the attention of English newspapers to David Low because they'd seen how successful and how good his work was. Apparently Billy Hughes was presented with a copy of this book and he immediately screwed it up and threw it in the bin, didn't like it. During the war the census did try to stop publication of some of Low's cartoons but The Bulletin actually stood by Low and tried to stop it.

But it's interesting in this period, when you read Low's biography which is strangely called, Low's Autobiography, there's a quote which is quite different to the approach of the other cartoonists and I read it out. 'It did not suit me to work in an office drawing ideas to order under the nose of an editor. I began to fall out of the paper's policy and mistrust for the ideas that went with it.' Then another quote. 'There came a day when in a spasm of integrity I refused to draw one of the editor's Jack monkey ideas to his great astonishment. Sit down, he said. I did and explained myself. I got everything off my chest.'

So he wasn't happy at The Bulletin and he didn't like the very polemic nature of The Bulletin and the way it expected its cartoonists to be and he started sending copies of his cartoons and the Billy book to English editors. He was a very ambitious man, he always I think wanted to go to London and eventually Henry Cadbury, one of the owners of The Star in London, was so impressed by his work that he offered Low a position on his paper. Low accepted and went – moved to London and over the next 30 years he'd become one of the best known cartoonists in the English-speaking world. He's perhaps best remembered for his anti-fascist cartoons that he did for the Evening Standard during the second world war and this is one of the most famous ones which is done just after Dunkirk.

So I should wrap up. The Bulletin began to fade in importance after the first world war. There was competition from other newspapers, magazines, particularly Smith's Weekly, that really impacted on The Bulletin's audience. It had a brief comeback in the 1960s under Donald Horne but it was a – by the end of the 20th century it was a bit of a shadow of its former self and in 2008 it ceased publication.

So what can we say about the cartoonists of The Bulletin? I think you can say they were hugely popular and particularly in that early period helped produce one of the most successful national weekly papers in the history of Australia. I think the early cartoonists are very interesting 'cause you can see them grappling with how to articulate a national voice for Australia. They anticipated the formation of the Australian nation and they came up with metaphors like the little boy from Manly to express that.

I think when you look back at the work of The Bulletin artists it gives you a window into how many Australians saw the world at this time, you can see issues like racism, sexism and also pride and nationalism all reflected in their work. So whatever you feel about these images I think it's a very valuable magazine for understanding Australia. Thank you.

Applause

S: Thank you, Guy. I think I'm going to have to get a copy of the Billy book to have a look at it. Now we have time for questions, if you have any questions please raise your hand and wait for the microphone to come to you. That's for the benefit of those people watching live on our Facebook stream and also for those of you using the hearing loop.

A: Thank you very much, that was very interesting. What about Oliphant? Did Oliphant ever work for The Bulletin?

G: I haven't seen his work in – Oliphant went over to America but I think he was – was he South Australian originally?

A: He was, yes.

G: Yeah but I'm not familiar with him being on The Bulletin. For this particular paper I really focused on the period 1880 to 1914 and Oliphant of course is post world war two. Yeah, Oliphant is just a – yeah, you're right, Oliphant is one of the people they point to as being one of the great Australian cartoonists who went overseas.

A: I'm interested in the technology used. When that cartoon of Edmund Barton holding the infant Australia, you said something about a new process that had a photo in it.

G: Yes.

A: How do we actually get from an original artwork which presumably was ink on a piece of paper to a picture printed in a magazine? What are the steps there?

G: Very good question. I'll do my best to answer it but I can't claim I fully understand. So it's – in some ways it's much easier to understand the earlier wood block engraving process because that's a mirror image being cut out of the wood block and then that wood block being used and you see those early Bulletin cartoons have got that quite – and the Punch cartoons have that quite stiff thing. What I think happened with the new photo engraving technology which came in in the 1880s, it allowed artists to draw onto large artboards and you can see the scale of the work. When you go into the exhibitions the cartoons from that period are huge, they're massive and then they went through a photographic process which was transferred to some kind of printing plate.

Exactly how that was done I'm not sure and there's a number of different photo-engraving processes over the years so later on, I think after world war one, you have - letter press printing is replaced by other sorts of printing so this is not the only time that printing technology changes how cartooning looks. But specifically the shift, the reason why you can move – the photo engraving process did allow artists to express themselves much more freely 'cause it wasn't being reinterpreted by a wood block maker and there was just more capacity in terms of showing shades and colour. So the Norman Lindsay cartoons for example, you begin to see shades come into that. That would not be possible in the earlier wood block period. That's hence the crosshatching you see in older wood block cartoons, that's how they do their shade.

A: That was really very interesting, thank you very much. I'm wondering about the use of balloons for dialogue and I don't think we've seen very much of that in the presentation you've given us and I'm wondering whether that was driven more by technological advances or by just the idea someone had that this is a very good way to enrich the picture.

G: Well balloons were used a lot in the earlier Georgian satire cartoons. I may even be able to find you an example. No, I don't know if I have a copy here but the – so you look at the earliest Georgian satirical prints which are people like Gillray, you'll see these massive talk balloons with huge amounts of text written in them and so it was a convention in cartooning. But once they go over to wood block printing I think it's quite difficult 'cause those are actually done as plates, they're not done – they're etchings rather than wood block prints. But once you get to magazines like Punch I think they just try and simplify everything so the number of characters reduces, the use of talk balloons reduces and the captioning is done on the bottom, usually printed on the bottom so you get this different convention of cartooning emerging.

Of course there's a different cartooning history which I'm not talking about today which is comic strips and then in comic strips you start having those talk balloons and things used in those so all through the 20th century you have - another history of cartooning relates to comic books and things like that. So today you'll get artists like Cathy Wilcox and things like that that will use a talk balloon so it's come in and out of editorial cartoon.

A: Sorry, this is going back to my childhood. Grade 6, Loxton Area School. The cartoon that you had with the Japanese man leaning over the boy from Manly and the ink bottle spilt, we were sitting down behaving ourselves. The teacher came in and the ink bottle had been tipped and there was this big splotch of ink and of course he was extremely unhappy, roared, the person who did it was told to come out and clean it up. He went out and it was when plastic was first invented, he picked up the ink blot, the ink bottle itself still had its lid on and it was a situation where you didn't know whether you were permitted to laugh or not because of the reputation of this particular teacher.

G: Wise not to, I think.

A: Guy, thanks for that, very good.

G: We've got an expert in the audience.

A: Just a word about the caption bubble. I don't know when it became more popular in political cartoons but the underlying idea was if you had the caption underneath, and that was quite late in the piece, that could always be subject to editorial change and second-guessing. But if you put a caption bubble in the drawing as part of its composition it was there to stay and it was expected that the cartoonist would not only do the drawing but provide the comment as well.

G: I think that's very interesting, Geoff, 'cause we've got a big Molnar collection in the Library and the – Molnar always liked to write a caption underneath and in The Herald it was printed but we've got his original cartoons where he's written down the caption and then I think sometimes you've got posted over the top an editor's changed it and you can see that playing out.

I don't know, Geoff, if you're able to give a better answer on the printing reproduction process than me 'cause – in terms of the importance – the shift from wood block to photo-engraving and letter press and how that impacted on how artists work.

A: I don't think I can, Guy, that was largely –

G: It had already happened.

A: I think my early days it was photo-engraved and the photographs there was a screen, a dot screen through the image that provided the gradations but – and I think the cartoons and the free hand artwork were subject to the same sort of treatment but then after that it became digitised and it was all different.

S: That looks to be it for questions. Can you all join me in thanking once again Dr Guy Hansen?

Applause

S: If you haven't already done so we now invite you to go upstairs to the ground floor to see the exhibition, hopefully not for the first time that you'll be seeing it and if that's not enough you can go to our bookshop and buy the catalogue for 10% off for those of you viewing on the Facebook stream. It is also available online. I'd also like to encourage anyone watching on the [live] 56:44 stream to go and have a look and for those in the audience as well to go and have a look at our podcast and our other streams on the Facebook page. We have a wonderful big swathe of collection that you can go back and view our previous events.

Thank you, everybody, for attending this afternoon and we'll hope to see you back at the Library again soon. Thank you.

Applause

End of recording