An enlightened world

The Americas

British colonisation of the Americas began in 1606 with the chartering of the Colony of Virginia. Establishing colonies overseas was strategically important to England and other European powers. Colonies provided:

- Access to land and trade routes

- Defensive positions

- Resources such as timber, cotton, furs and labour

The British also used the Americas as a destination for penal transportation. Overcrowded jails and harsh sentencing in 17th- and 18th-century England led to the Transportation Act 1717, which allowed convicts to be sent to the colonies for up to 14 years. Returning before the sentence ended was a capital offence.

The American Revolution

Between 1765 and 1783, the British colonies in North America staged a revolt against the British Crown. The colonists objected to:

- Taxation without representation

- Laws imposed by a parliament in which they had no voice

The Stamp Act 1765 imposed a direct tax on printed materials. In response, nine colonies convened the Stamp Act Congress, issuing the Declaration of Rights and Grievances, which included:

- The right to trial by jury

- Objections to Admiralty Courts

- The principle that only colonial assemblies could impose taxes

Although the Stamp Act was repealed in 1766, the Declaratory Act asserted Britain’s right to legislate for the colonies “in all cases whatsoever”.

The conflict escalated from civil disobedience to war. The American Patriots, as they called themselves, with support from France and Spain, ultimately defeated the British and won independence.

Antoine Phelippeaux and Jacques Grasset de Saint-Sauveur, Tableau des decouvertes du Capne. Cook & de la Perouse, 1798, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135227083

Antoine Phelippeaux and Jacques Grasset de Saint-Sauveur, Tableau des decouvertes du Capne. Cook & de la Perouse, 1798, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135227083

Stamp Act 1765

In March 1765, the British parliament passed the Stamp Act, imposing a direct tax on the colonies. It required that legal papers, newspapers, cards and pamphlets be printed on specially taxed paper from London. The tax had to be paid in British currency, not colonial currency.

In response, 9 colonies convened the Stamp Act Congress in October 1765. They issued the Declaration of Rights and Grievances, which set out 14 objections. These included:

- colonists owed to the Crown ‘the same allegiance’ owed by ‘subjects born within the realm’

- colonists owed to the parliament of Great Britain ‘all due subordination’

- colonists possessed all the rights of Englishmen

- trial by jury was a right

- the use of Admiralty Courts was abusive

- without voting rights, the British parliament could not represent the colonists

- there should be no taxation without representation

- only the colonial assemblies had a right to tax the colonies.

After petitions and Benjamin Franklin’s speech to parliament, the Stamp Act was repealed in 1766. But on the same day, parliament passed the Declaratory Act, asserting its authority to legislate for the colonies “in all cases whatsoever”.

The Treaty of Paris (1783)

In 1783, representatives of the British government and the soon-to-be United States signed the Treaty of Paris) in France. The treaty formally ended the American Revolutionary War and outlined the conditions for peace. Its first article recognised the United States as an independent nation and successor to the former colonies. Britain also agreed to relinquish all claims to territory east of the Mississippi River, north of Florida, and south of Canada.

Some historians argue that the treaty favoured the United States. Others suggest that British Prime Minister Lord Shelburne saw the potential for the United States to become a valuable economic partner. By ceding large areas of land and allowing the new nation to grow, would open lucrative trade options.

This proved correct. Britain gained access to American resources without the burden of governance. The war had cost Britain an estimated £12 million per year, and by 1783, its national debt had reached £250 million—equivalent to approximately £28.6 billion or A$51.3 billion today.

The Treaty of Paris

Preamble.

Declares the treaty to be ‘in the name of the most holy and undivided Trinity’, states the bona fides of the signatories, and declares the intention of both parties to ‘forget all past misunderstandings and differences’ and ‘secure to both perpetual peace and harmony’.

- Britain acknowledges the United States (New Hampshire, Massachusetts Bay, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia) to be free, sovereign, and independent states, and that the British Crown and all heirs and successors relinquish claims to the Government, property, and territorial rights of the same, and every part thereof;

- Establishing the boundaries of the United States, including but not limited to those between the United States and British North America;

- Granting fishing rights to United States fishermen in the Grand Banks, off the coast of Newfoundland and in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence;

- Recognising the lawful contracted debts to be paid to creditors on either side;

- The Congress of the Confederation will ‘earnestly recommend’ to state legislatures to recognise the rightful owners of all confiscated lands and ‘provide for the restitution of all estates, rights, and properties, which have been confiscated belonging to real British subjects’ (Loyalists);

- United States will prevent future confiscations of the property of Loyalists;

- Prisoners of war on both sides are to be released; all property of the British army (including slaves) now in the United States is to remain and be forfeited;

- Great Britain and the United States are each to be given perpetual access to the Mississippi River;

- Territories captured by Americans subsequent to the treaty will be returned without compensation;

- Ratification of the treaty is to occur within six months from its signing.

Eschatocol.

‘Done at Paris, this third day of September in the year of our Lord, one thousand seven hundred and eighty-three.’

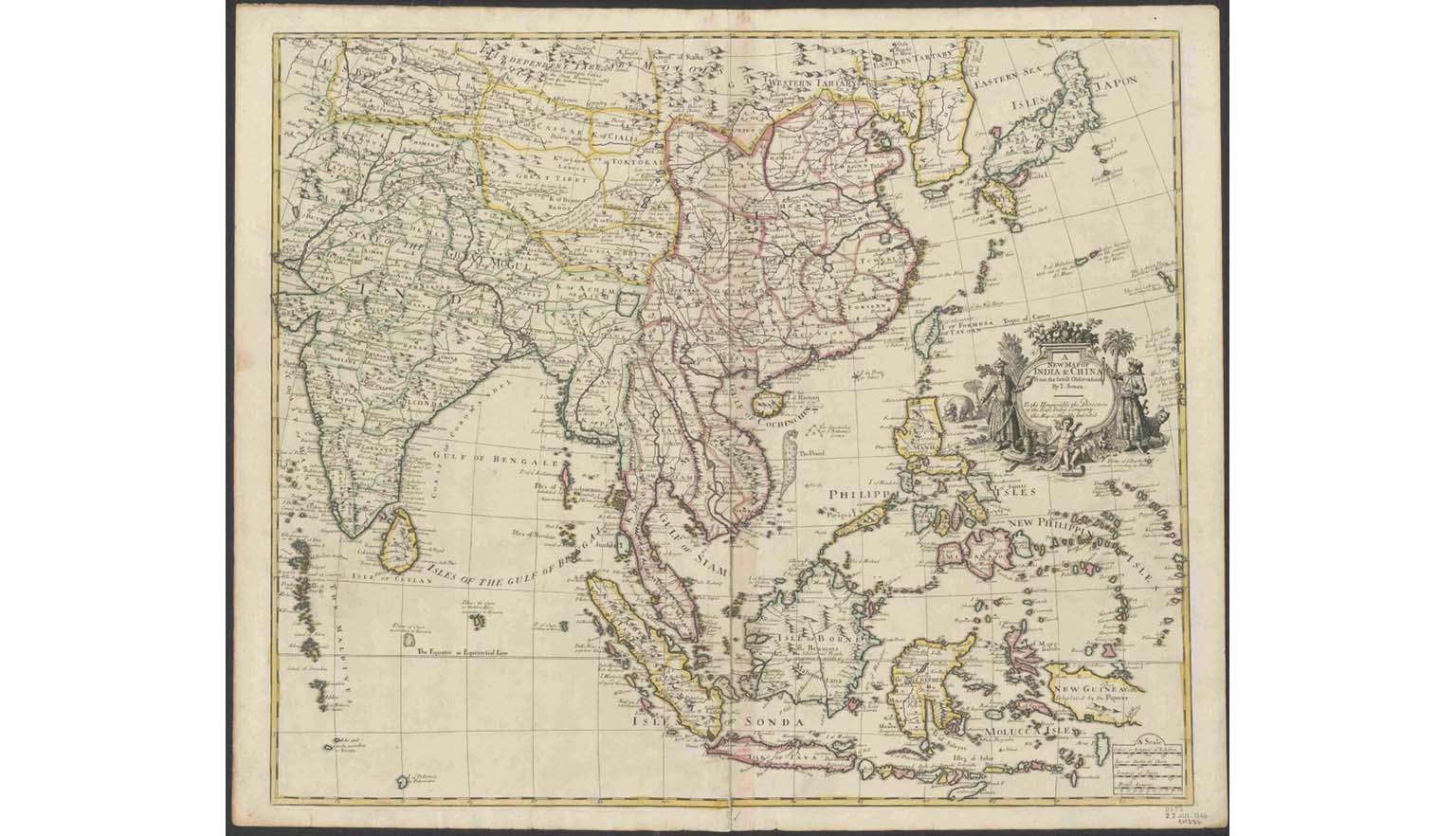

Asia

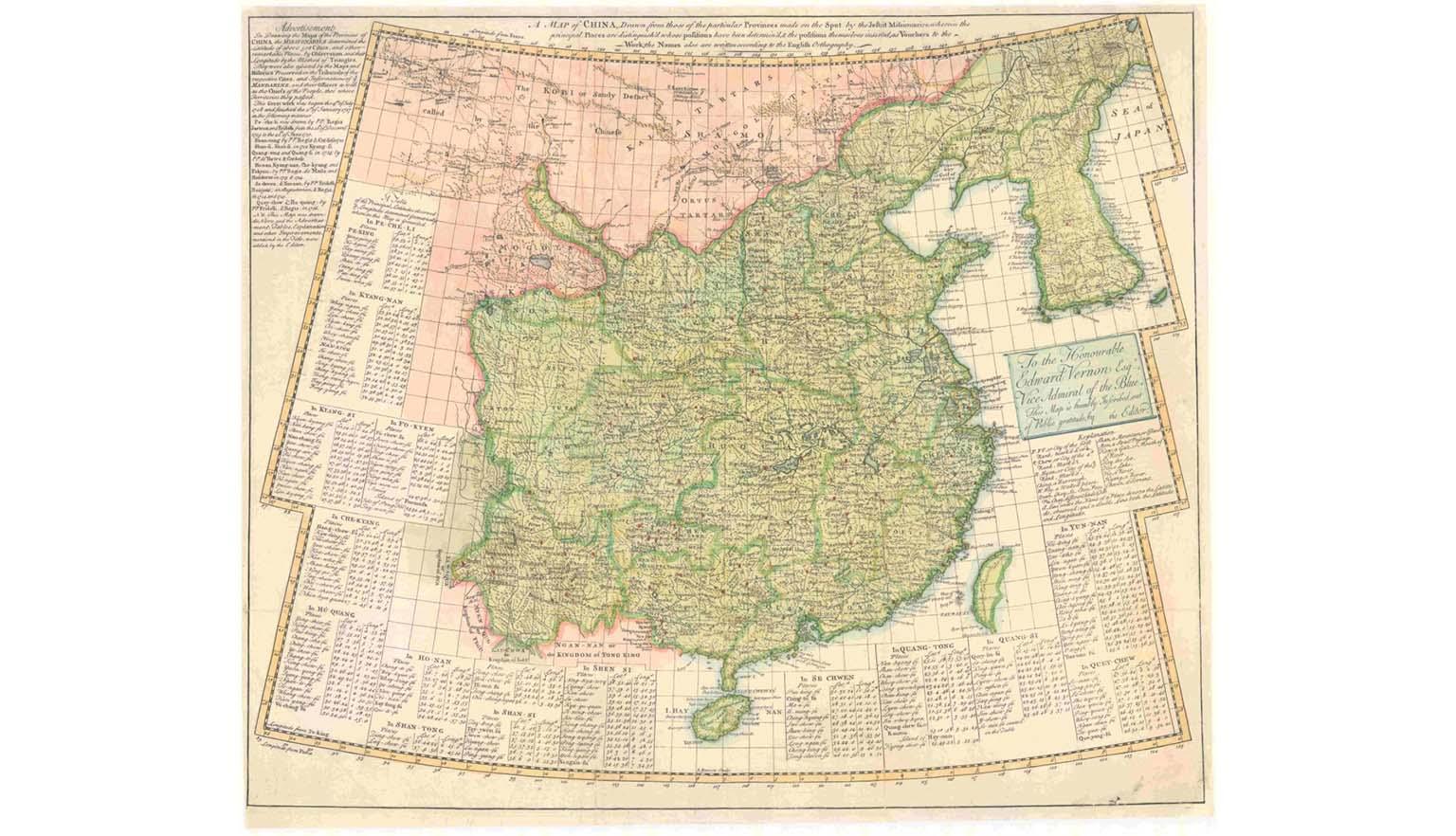

The 18th century in China was defined by the reigns of two of its longest-serving emperors in Chinese history: the Kangxi Emperor (ruler from 1661 to1722) and his grandson, the Qianlong Emperor (ruler from 1735 to 1796). During this period, the Qing dynasty reached the height of its power, ruling over approximately 13 million square kilometres. For comparison:

- Modern China covers 9.6 million square kilometres

- Russia spans 17.1 million square kilometres

- Australia covers 7.74 million square kilometres

Reform and control

Throughout the 1700s, the Qing government launched major reforms to strengthen internal governance and secure its borders. After Kangxi’s death in 1722, his son, the Yongzheng Emperor, reversed many of his father’s edicts. He promoted Confucianism, expelled Christian missionaries, and outlawed Christianity in 1723. Several anti-Manchu writers previously pardoned by Kangxi were executed.

Yongzheng also expanded the Palace Memorials system—direct communication between local officials and the emperor. This bypassed the bureaucracy, allowing the emperor to receive uncensored reports and impose decisions without interference.

Population growth and agricultural pressure

China’s population remained relatively stable during the 17th century due to internal conflict and epidemics. However, under Qing rule, peace and prosperity led to rapid growth. Between 1700 and 1800, the population tripled—from 100 million to 300 million.

The introduction of New World crops such as potatoes and peanuts improved food security. But as all arable land was eventually used, farmers were forced to cultivate smaller plots more frequently. This led to soil degradation and declining crop yields.

Foreign trade and resistance

By the late 18th century, European powers—particularly Britain and France—sought stronger trade relationships with China. Under the Canton System, foreign merchants were restricted to trading in Canton (Guangzhou). The system:

- Controlled where trade could occur

- Imposed fixed prices on imports and exports

- Required foreign merchants to pay taxes

- Limited Chinese citizens’ contact with foreigners

To further restrict foreign influence, the Qing government issued the Five Counter-Measures Against the Barbarians.

Five Counter-Measures Against the Barbarians (Fáng yí wŭ shì, 防夷五事)

Also known as the Vigilance towards Foreign Barbarian Regulations (Fángfàn wàiyí guītiáo, 防范外夷规条), these measures included:

- Trade by foreign barbarians in Canton is prohibited during the winter.

- Foreign barbarians coming to the city must reside in the foreign factories under the supervision and control of the Cohong.

- Chinese citizens are barred from borrowing capital from foreign barbarians and from employment by them.

- Chinese citizens must not attempt to gain information on the current market situation from foreign barbarians.

- Inbound foreign barbarian vessels must anchor in the Whampoa Roads and await inspection by the authorities.

The Macartney mission

By the 1790s, European frustration with China’s trade restrictions had grown. China demanded silver in exchange for goods and refused to accept foreign products in return. This created a trade imbalance that drained European silver reserves.

In 1793, Lord George Macartney, representing the British East India Company, travelled to China to request a free trade agreement. Britain viewed trade as essential to its economic strategy. China, however, did not rely on foreign trade and saw little value in foreign goods.

The Qianlong Emperor rejected the proposal, stating:

The kings of the myriad nations come by land and sea with all sorts of precious things … there is nothing we lack.

Learning activities

These activities help students explore the causes of the American Revolution, the significance of political representation, and the broader influence of the European Enlightenment.

Activity 1: Representation and revolution

The American colonies revolted in part because they had no representation in the British Parliament.

- Begin with a class discussion:

- Why would the colonists have been angered by their lack of representation?

- What benefits might they have gained by having a representative in the British Parliament?

- Discuss the broader idea of political representation:

- Why is it important for people to have a voice in government?

- What are the risks when groups are excluded or under-represented?

- Ask students to consider:

- What could Britain have done differently to reduce the risk of revolution, while still maintaining administrative control?

- Could compromise or reform have changed the outcome?

- Extend the conversation with historical or modern parallels:

- Can students identify other examples—past or present—of people who lacked representation?

- Are there groups in Australia or other countries today with little or no voice in government?

Activity 2: Global impacts of the Enlightenment

The European Enlightenment was a powerful intellectual movement. Its ideas travelled far beyond Europe.

- Ask students to choose a country or region outside of Europe.

- Have them research and respond to the statement:

“The European Enlightenment had repercussions for the world.” - Students should consider:

- How Enlightenment ideas (such as individual rights, reason, liberty or scientific inquiry) may have influenced people, movements or institutions in that region.

- Whether the impacts were positive, negative, or both.

Activity 3: Enlightenment timeline project

Students will work in groups to build a class timeline of key events and figures from the Enlightenment.

- Divide the class into groups. Assign each group a focus area:

- Key thinkers and philosophers

- Scientific discoveries and inventions

- Social or political revolutions

- Conflicts or resistance to Enlightenment ideas

- Ask each group to research and contribute:

- 4 to 6 milestones for their area

- A short explanation of why each item is significant

- As a class, create a shared timeline (on paper or digitally).

- Together, develop and apply criteria for inclusion:

- What makes a person, idea or event influential or ‘worthy’ of inclusion?

- How do we judge the long-term impact of an idea?