Science

The Enlightenment and science

The Enlightenment was a time of big ideas and bold challenges to tradition. Thinkers of the period believed society could be improved through reason. They called for changes like separating church and state and creating governments based on constitutions.

In science, Enlightenment thinkers promoted the power of rational thought. They questioned religious beliefs and superstitions, arguing that knowledge should come from reason and evidence. Scientists embraced the scientific method and began breaking complex ideas down into simpler parts to understand how the world worked.

The study of nature thrived during this time. Plants, animals, places and peoples were examined with fresh eyes and a logical approach, moving away from the mystical explanations of the past.

Carl Linnaeus

Born in Sweden in 1707, Carl Linnaeus had a love of nature from the start. His father, a keen gardener, introduced him to botany and taught him that every plant had a name. Back then, plant names were long and detailed descriptions in Latin. For example, the plant we know today as Plantago media (hoary plantain) was previous called Plantago foliis ovato-lanceolatus pubescentibus, spica cylindrica, scapo terete (‘Plantain with pubescent ovate-lanceolate leaves, a cylindric spike and a terete scape’) — a mouthful even for experts!.

As Linnaeus studied plants, animals and minerals, he saw the need for a simpler, more organised system. He created a way of classifying living things using just two names — a genus (group) and a species (type within that group). This binomial system was clear, logical and reflected the spirit of Enlightenment thinking.

Linnaeus’ system

All natural things (plants, animals and minerals) can be described using the classification system developed by Linneaus.

- Domain – Archaea, Bacteria, Eukarya

- Kingdom – Animal, Plant, Fungi

- Phylum – Chordata (with spinal cord), Arthropoda (jointed foot), Coniferophyta (plants with cones)

- Class – Vertebrata (with vertebrae), Tetrapoda (with four limbs)

- Order – Primates (first, highest rank), Carnivora (meat eaters), Artiodactyla (even-toed)

- Genus – Homo (man-like), Felis (small to medium cats), Canis (dog-like), Panthera (big cats)

- Species – Homo sapiens (modern humans), Felis catus (domestic cats), Canis lupus (wolves)

Before Linnaeus, a tiger might have been described as a ‘four-legged, meat-eating animal that looks like a cat and has stripes’. Linnaeus grouped animals with shared traits into broader categories, like the big cat genus Panthera.

Linnaeus is remembered as the father of modern taxonomy and one of the founders of modern ecology. His ideas shaped how we understand and study the natural world. His legacy lives on through the Linnean Society, which still promotes research in natural history, evolution and taxonomy.

Daniel Solander

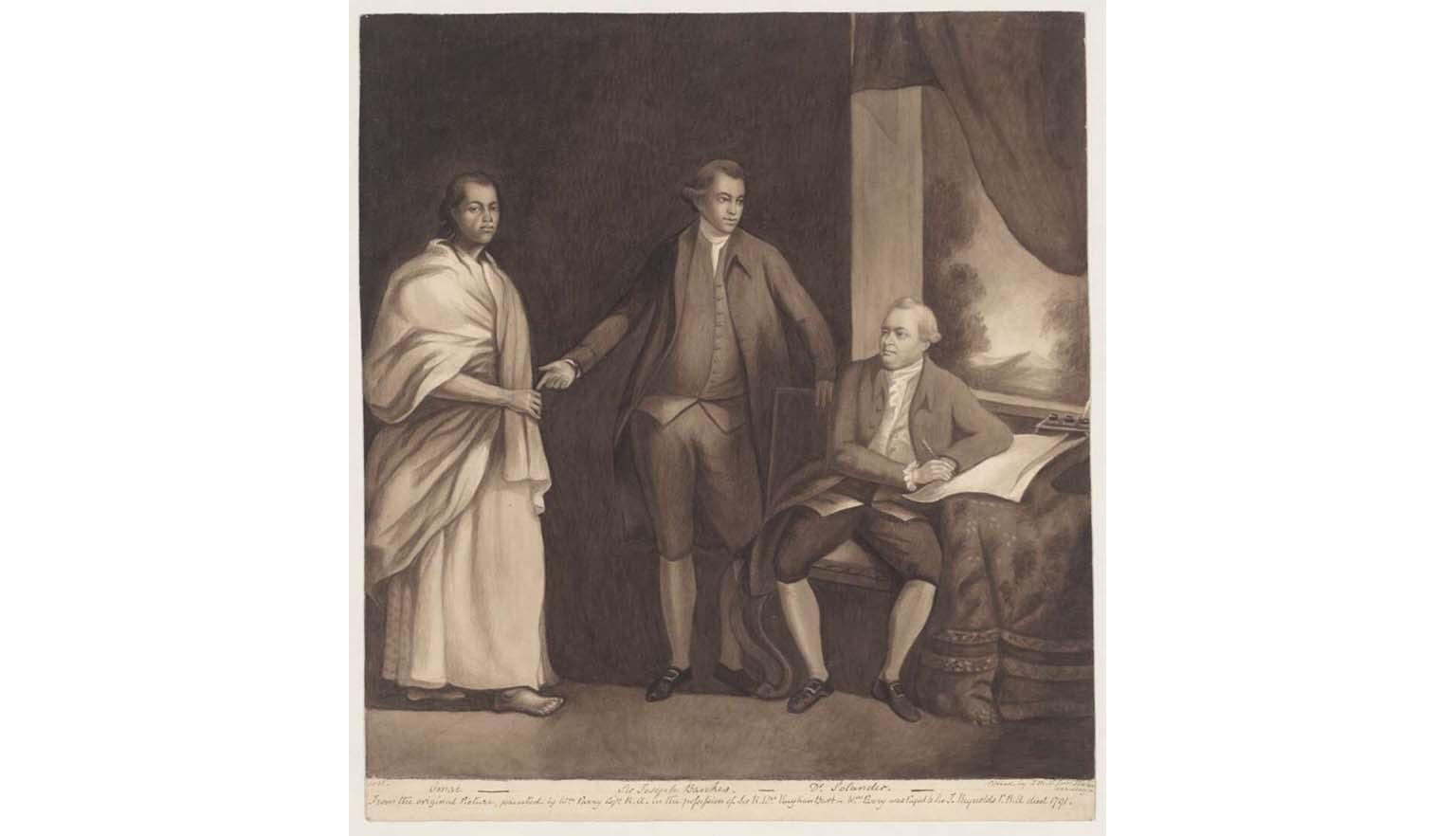

Daniel Solander was born in Sweden in 1733. At the University of Uppsala, where he studied languages and humanities, he met Linnaeus. Linnaeus encouraged him to study natural history. Solander later moved to England, where he worked at the British Museum cataloguing collections and promoting Linnaeus’ ideas. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1764.

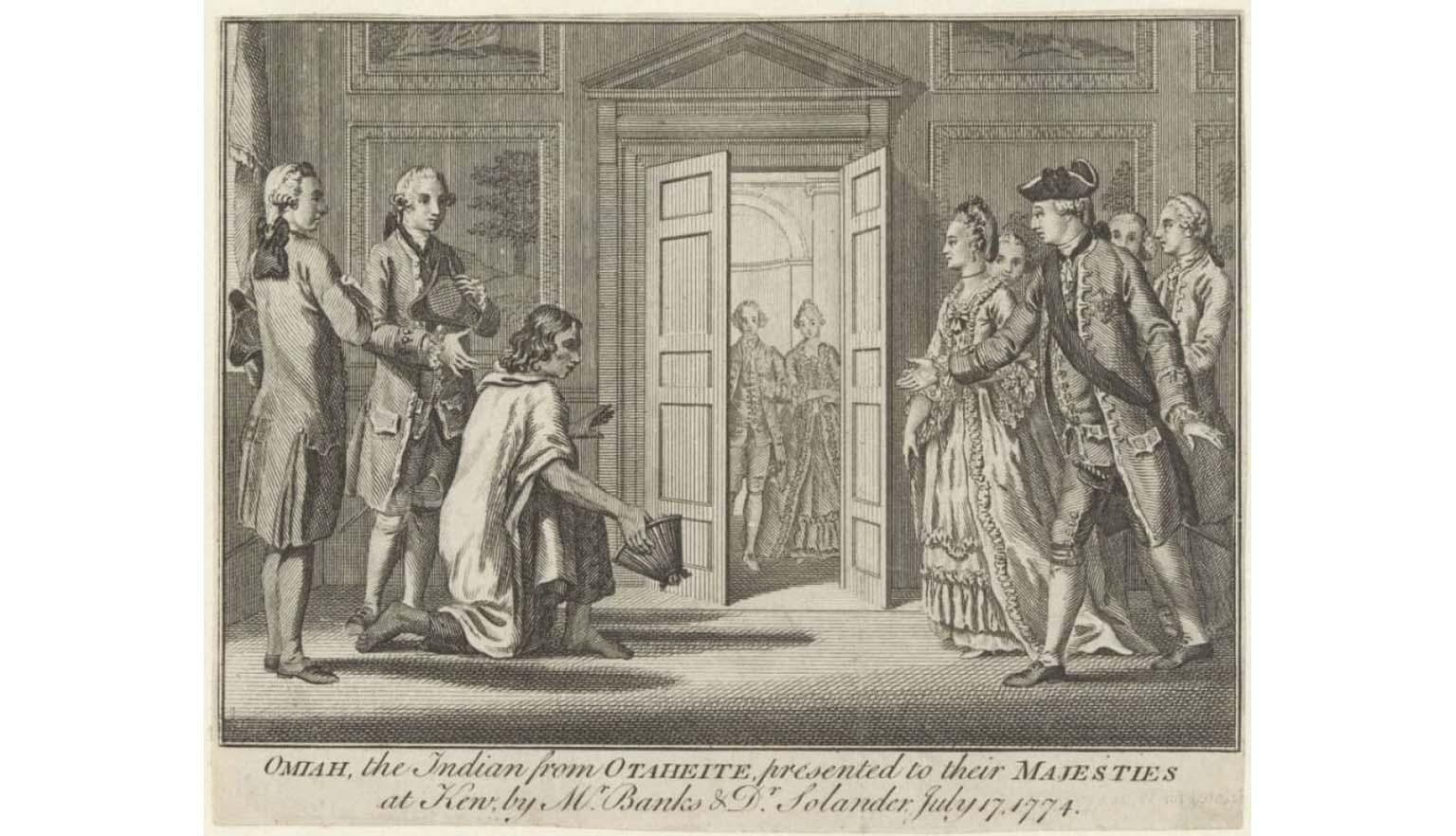

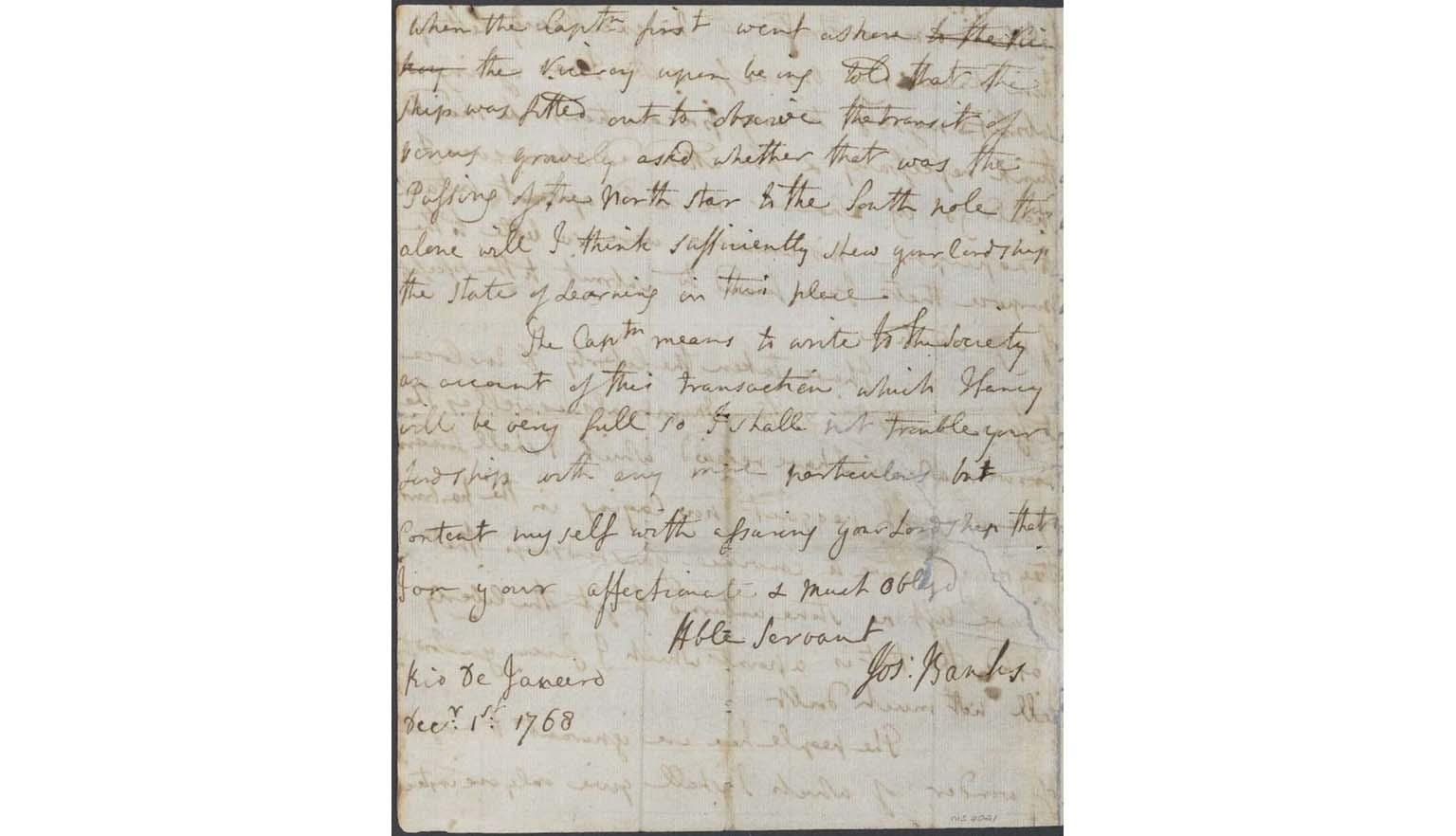

In 1768, Joseph Banks invited Solander to join the scientific team on HMB Endeavour. Solander helped document plants and animals, some unknown to Europeans. He was one of the botanists who inspired the name ‘Botanists Bay’ (later Botany Bay). He collected specimens from at least eight countries and became the first university-educated person to set foot in Australia, as well as the first Swedish person to circumnavigate the globe.

Solander and Banks collected more than 30,000 plant samples, including 1,400 species not previously known to Western science. Solander contributed to Banks’ Florilegium, a collection of botanical engravings. Although he published little in his lifetime, his work left a lasting mark on science.

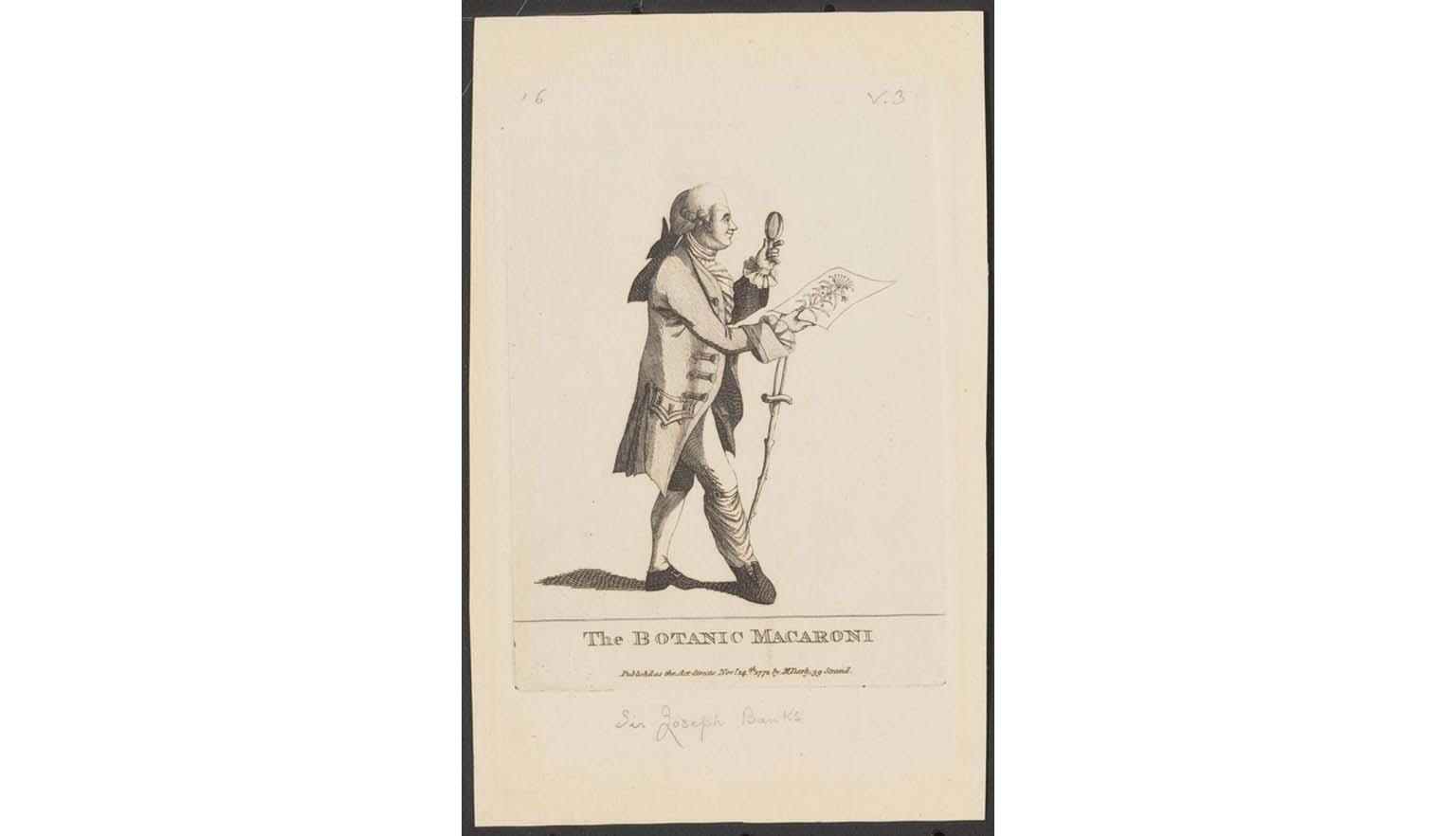

Joseph Banks

Joseph Banks was born in London in 1743. He developed an interest in botany while growing up in the Lincolnshire countryside. At the University of Oxford, he paid a botanist to give lectures on plants — rare at the time. Banks left Oxford without a degree but continued to study nature at places like the Chelsea Physic Garden and the British Museum, where he met Solander.

In 1768, Banks joined Captain Cook’s South Sea expedition on the Endeavour. Banks saw the scientific potential of the voyage and assembled a team of scientists and artists, including Solander. They collected plants, animals and cultural observations throughout the journey.

Banks became president of the Royal Society in 1778, serving for 41 years. The Society promoted science and encouraged voyages of discovery. Its motto, Nullius in verba (‘Take nobody’s word for it’), reflected Enlightenment ideals of seeking knowledge through experience rather than tradition.

As president, Banks organised expeditions to collect specimens from around the world. He was seen as an authority on Australian plants and people and advised the first governors of the colony.

Learning activities

Use these activities to explore how we classify living things, the limits of scientific knowledge, and the unique biodiversity of Australia.

Activity 1: The value of classification systems

- What are the advantages to having a formalised classification system for plants and animals?

- What are the drawbacks?

Critique the current system and suggest improvements.

Activity 2: Plant discovery and scientific limits

Between them, Banks and Solander catalogued over 30,000 new plant species. This increased the number of species known to Western science by 10%.

- Is it possible that there are still such quantities of plant and/or animal species left on the planet to document?

- Is it likely that we can reach ‘peak discovery’ (a point where we have discovered all there is to know)?

- Have we already reached it?

As a class, choose a standpoint, conduct further research and stage a debate.

Activity 3: Local flora study

Australia abounds with trees, shrubs and flowers found nowhere else on Earth.

- Document the different species of plants found in your school, neighbourhood or community.

- Work out which are native to Australia and which have been introduced.

- Which species are endemic to your region?

- Which are from other areas of Australia or abroad?

Compile a florilegium with the results.