The Last Dragon

Author talk: The Last Dragon

Postscript from Charles Massy

The following postscript, written by Charles Massy, is taken from The Last Dragon.

Massy highlights the impact that farming and grazing have had on the Monaro plains. As a result, the once vibrant habitat has changed substantially, threatening the future of the Monaro grassland earless dragon.

Author Talk: The Last Dragon

The Monaro grassland earless dragon

The Monaro grassland earless dragon (Tympanocryptis osbornei, or ‘Osborne’s hidden-ear dragon’) is one of Australia’s rarest reptiles.

Small and weighing between 6 and 9 grams, the dragon has a very short lifespan. It lays three to six eggs once a year, just under the ground where sunlight warms them. These nests can dry out or be disturbed by hooves, machinery or predatory insects, leading to sudden local population loss.

Habitat damage has severely impacted dragon numbers. Open grasslands, like those at Narrawallee, have been overgrazed by sheep and cattle, and damaged by ploughing, farming and building activities.

Custodians of the Monaro grasslands

Prior to the arrival of European settlers, and perhaps for more than 20,000 years, the Ngarigo nation were the custodians of the Monaro grasslands. They regularly burnt the grasses where the dragon lived, managing the land carefully and skilfully to promote a sustainable food supply (including perhaps the occasional dragon). This maintained the health and diversity of the grasslands, and the fauna living within them.

European settlement and the changing landscape

Captain Mark John Currie was one of the first Europeans to alert settlers to the rich and diverse Monaro grasslands. On 1 June 1823, he recorded in his diary: ‘passed through a chain of clear downs to some very extensive ones ... From ... natives we learned that the clear country before us was called Monaroo’. After this visit, the European settlers arrived and ‘took up’ country. The destruction of the Monaro grasslands started with the beginning of this settlement.

The problem was that the Australian climate - highly variable, with frequent droughts - and the ancient coevolved vegetation and generally poorer soils were vastly different to those in north-western Europe and Britain where the settlers came from. Polish explorer Count Paul Strzelecki delivered a report to Governor Gipps in 1840 about his brief travels through the Monaro. He told Gipps that the effects of the drought at that time were not just due to the climate and overburning of the grass by squatters, but to:

the alteration which colonisation impresses on its surface; the herbaceous, high and thick plants ... which so well clothed the crust and sheltered the moisture, have disappeared under the innumerable flocks and axes which the settlers have introduced. The soil, thus bared, was and is ... abandoned ... The disturbance ... extends the dryness of the soil, augments its aridity …

That is, poor management from overgrazing by sheep and cattle was the destroyer of both grasslands and grassy woodlands, and therefore of the Monaro’s plant and animal biodiversity.

Historical accounts of land degradation

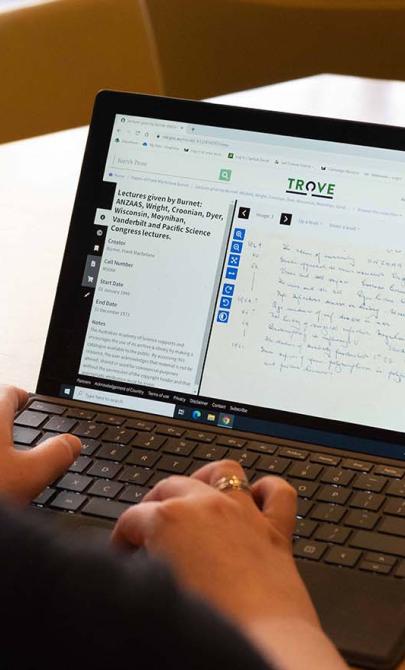

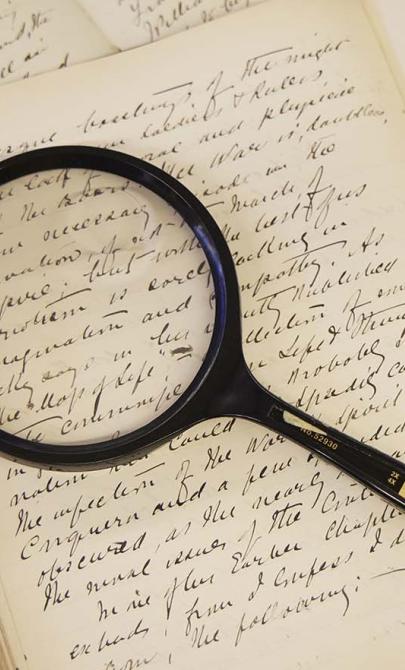

In his famous book, Discovering Monaro. A Study of Man’s Impact on His Environment (1972), historian W.K. (Keith) Hancock was able to document this ‘impact’ of European mismanagement. His extraordinary research notes and papers for the book are held in the archives of the National Library of Australia.

Hancock revealed that, upon the arrival of European settlers, the native fauna was so abundant that they regularly shot lyrebirds and other, now rare, animals for sport. Scottish visitor Farquhar McKenzie noted in his diary of 1837 that: ‘When out shooting duck at Bredbow river I saw a number of those curious animals the Platibus and fired at them repeatedly.’

However, it was the overgrazing by sheep and cattle that continued to degrade the diverse flora and fauna of the Monaro grasslands, especially in drought times. This is graphically captured in a vivid recollection by Monaro settler William Crisp, whose records Hancock discovered.

Before the passing of the Land Act [the Robertson Land Act of 1861, which in places like the Monaro led to overstocking] ... the Matong Creek for about five miles ... was a succession of deep waterholes, there being no high banks, and grass grew to the water’s edge. Hundreds of wild ducks could be seen along these waterholes, and platypus and divers were plentiful. Five years after the passing of the Act the whole length ... became a bed of sand, owing to soil erosion caused by sheep ... the best grasses for cattle disappeared ... I have seen the kangaroo grass, when in seed, like a field of wheat three feet high. This disappeared, as also did many of the wild birds, including the duck and the turkey [the Plains bustard, a grassland bird].

As Hancock concluded: ‘there is nothing good to be said about what the squatters did to the pastures. In Monaro as elsewhere, they made one blade of grass grow where two had grown before’.

Survival of the Monaro grassland earless dragon

However, despite nearly 200 years of overgrazing, the Monaro grassland earless dragon did not become extinct.

These dragon-lizards were first discovered by scientists in 1907 when two specimens were collected and sent to the Australian Museum in Sydney. They were then considered extinct until the late 1980s when another scientist, Dr Will Osborne from the University of Canberra, found them again on the Monaro (which is why this little dragon is named after him).

Today, the dragon, a grassland specialist, remains close to extinction. It is placed very high on the endangered species list for Australia, and is one of the most endangered reptiles in the world. Fortunately, with the help of scientists, landholders like my family are implementing ecological grazing practices. At our farm, we also work with land manager Rod Mason, an Elder of the Ngarigo nation, incorporating traditional Indigenous land management practices into our attempt to preserve healthy temperate grasslands for the dragons. We all must do what we can to save these beautiful, cheeky, yet rarely seen, little animals!

About Charles Massy

Dr. Massy is widely known and has presented all over the world.

He became an advocate for regenerative farming during the 1980s drought, which forced him to radically change his approach to farming. He is the author of The Last Dragon as well as other books about the Australian sheep industry.

Dr. Massy has managed Severn Park, an 1820 ha sheep, and cattle property on the Monaro for 40 years.

Concern at ongoing land degradation and humanity’s sustainability challenge led him to return to university in 2009 to undertake a PhD in Human Ecology. He is a Research Associate of the Australian National University and has been awarded an OAM for services to the Wool Industry and Community.

Learning activities

Activity 1: Investigate local wildlife

Find out what animals are endangered or under threat in your area. How can the community help them survive? If there are no local examples, choose a familiar endangered animal from elsewhere.

Activity 2: Reflect on extinction

Read The Last Dragon (if available) and imagine what it would feel like to be the last of your kind.

If the book is not available, learn about Lonesome George, the last Pinta Island tortoise, or Benjamin, the last known thylacine (Tasmanian tiger).

Discuss how losing a species affects ecosystems and the wider world.

Activity 3: Research extinction in Australia

Investigate species that became extinct before modern humans, such as muttaburrasaurus and diprotodon.

Explore how more than 100 Australian species have gone extinct or extinct in the wild since 1788.

Activity 4: Debate human impacts

Hold a class debate on how human activity has affected Australian wildlife since European settlement. Consider:

- Changes in farming, land use and settlement patterns

- Living conditions and survival needs of settlers

- Scientific understanding of ecology at the time

- Other factors that may have contributed to species loss

Activity 5: Watch and learn

Watch Charles Massy and George Madani discuss the Monaro grassland earless dragon in the video event The Last Dragon.

Activity 6: Explore conservation efforts

Find out more about the conservation plan for the Monaro grassland earless dragon developed by the ACT Government.