Art

Painting

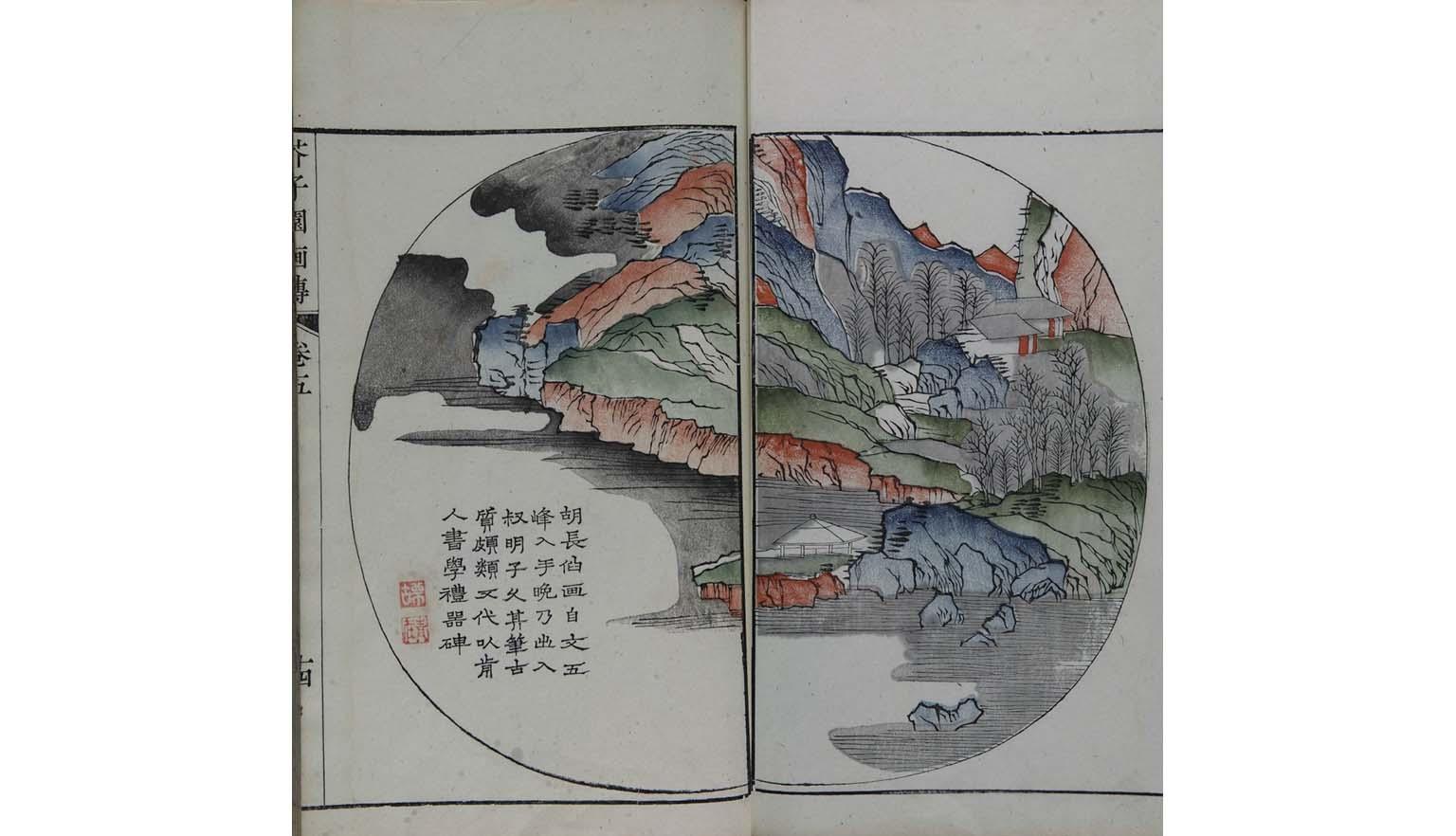

Painting was viewed as a respectable pursuit, and manuals on the subject became popular during the late Ming dynasty. Some were printed in multiple colours, using different woodblocks for each one. This interest continued into the early Qing dynasty with the publication of Painting Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden. Covering the general principles of landscape painting and the preparation of colours, it became one of the most renowned painting manuals in East Asia.

The first part, by Wang Gai and printed in five colours in 1678, discusses the painting of trees, hills and stones, people and buildings. It also includes examples by renowned masters. Two later parts, printed in 1701 by Wang and his two brothers, focus on the painting of plants, flowers, birds and insects.

Although it was later reproduced using a variety of methods, the first editions of the Painting Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden—printed in the late 17th and early 18th centuries—are important examples of colour woodblock printing. The technique originated in Asia, with the earliest surviving examples dating to the Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD).

Many renowned Chinese painters began their training with the Mustard Seed Garden, as did many Japanese artists of the Edo period.

Portraiture

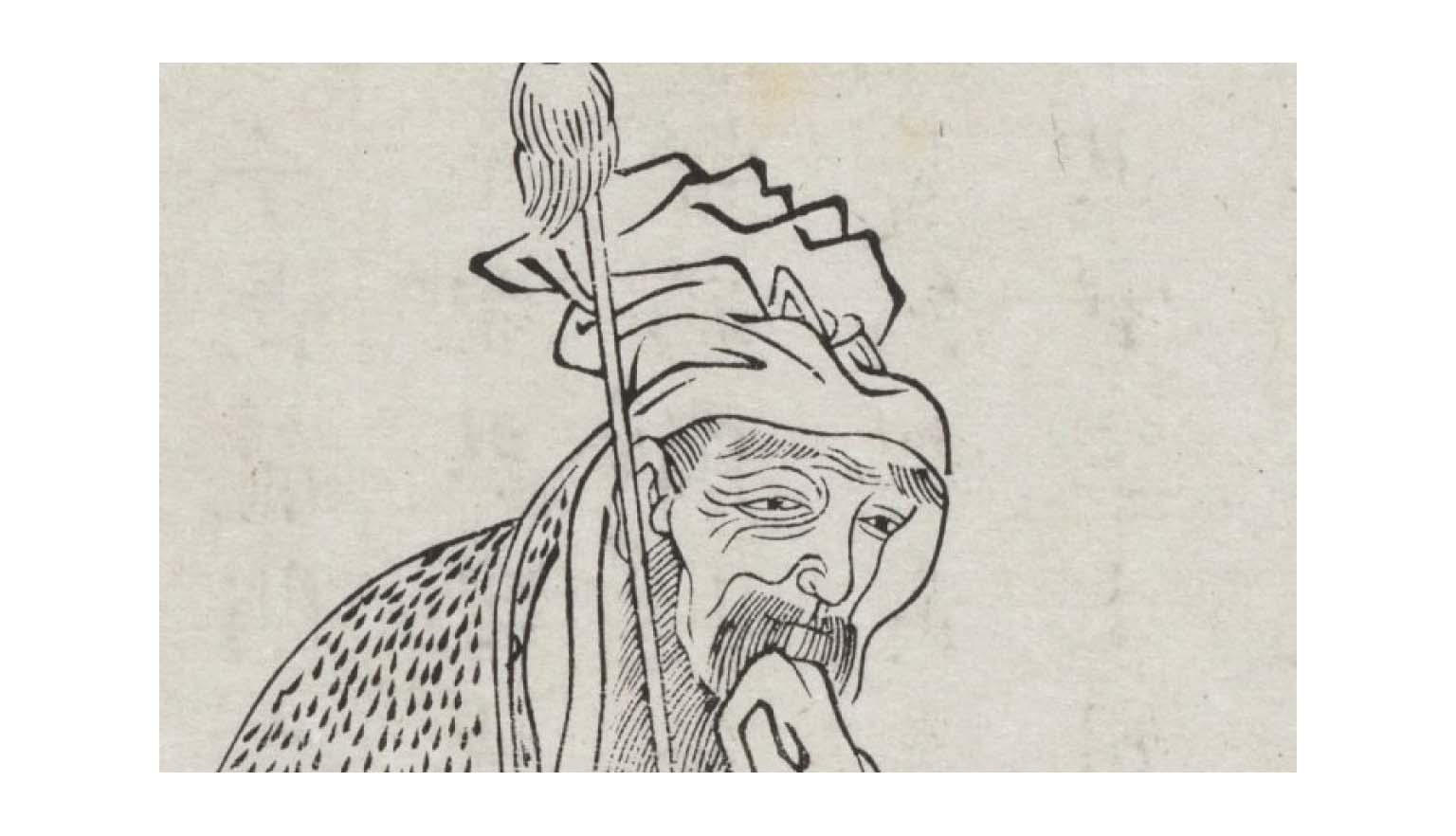

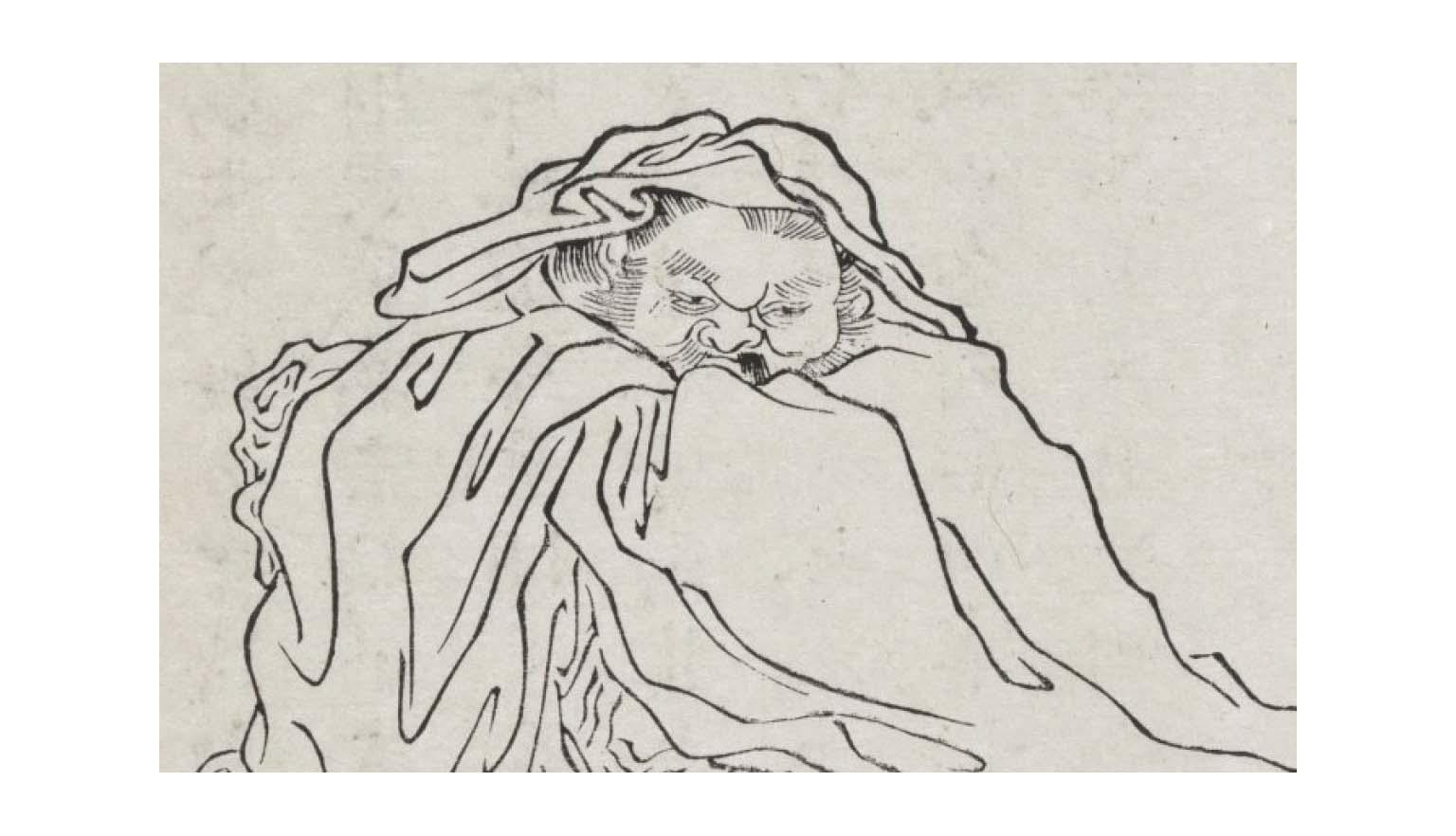

Portraits from the Hall of Late Blossoming contains 120 illustrations of men and women from Chinese history by artist Shanguan Zhou. While little is known about his life, paintings attributed to him can be found in galleries around the world. Each portrait is accompanied by a short biography.

The first image reproduced above shows Su Wu of the Han dynasty, an imperial envoy later exiled as a goat herder. The second image is of Tang dynasty poet Meng Haoran.

In the preface to Portraits from the Hall of Late Blossoming, Shanguan Zhou explains how he selected figures for inclusion:

These 120 do not account for all the ancients. Many more captured my imagination, but I have simply taken a few examples from among thousands to satisfy my personal preferences. Viewing them together, in addition to the meritorious ministers of the Ming, I find that I have included personages from the dynasties of the Han to the Ming; among them are princes, marquises, generals and ministers; the loyal, the filial, the conscientious and the righteous; poets, writers, calligraphers and painters; Daoists and Buddhists. I even find members of the fairer sex. It is just like gathering them all in a single hall and listening to their chatter.

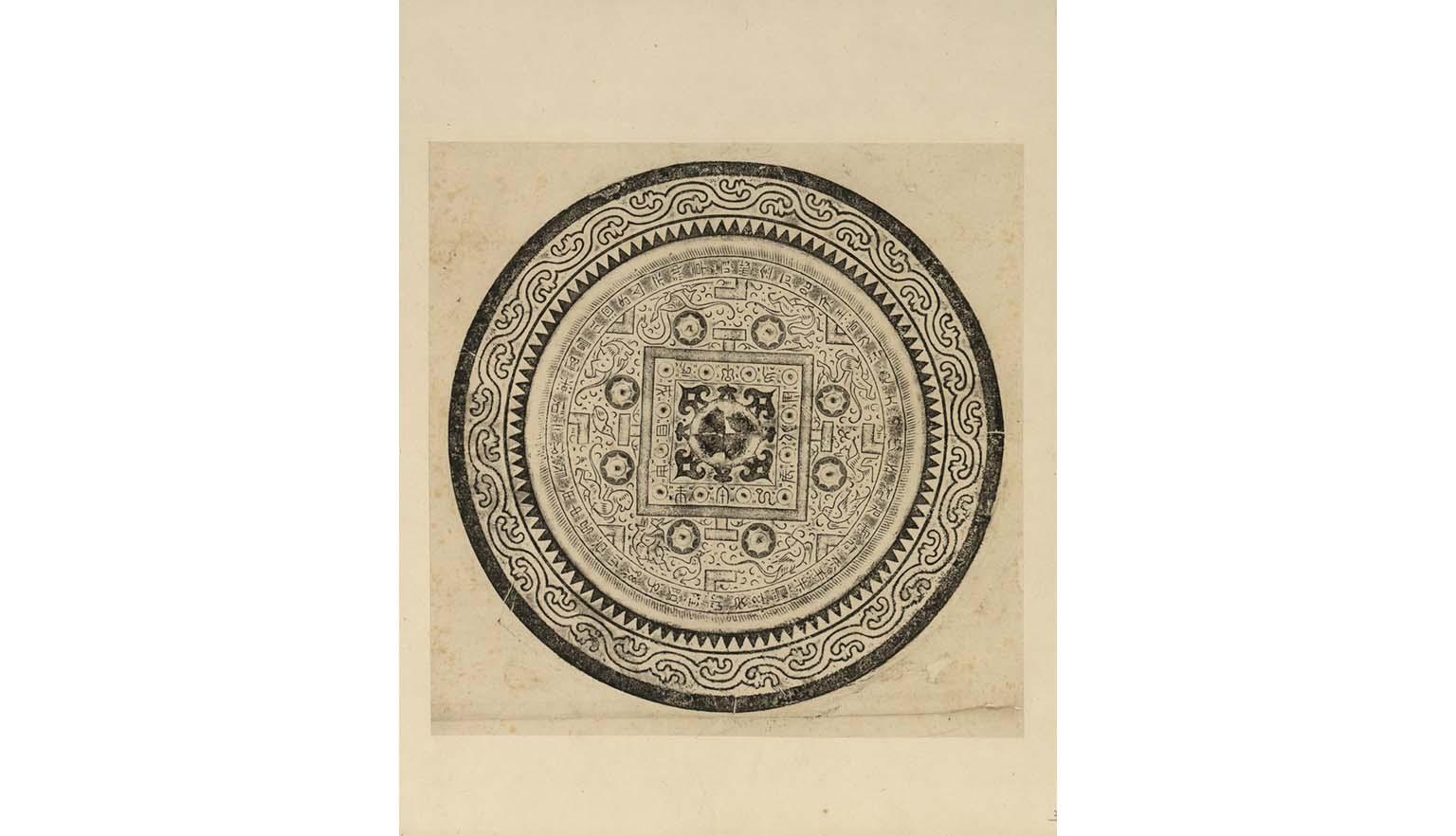

Rubbings and inscriptions

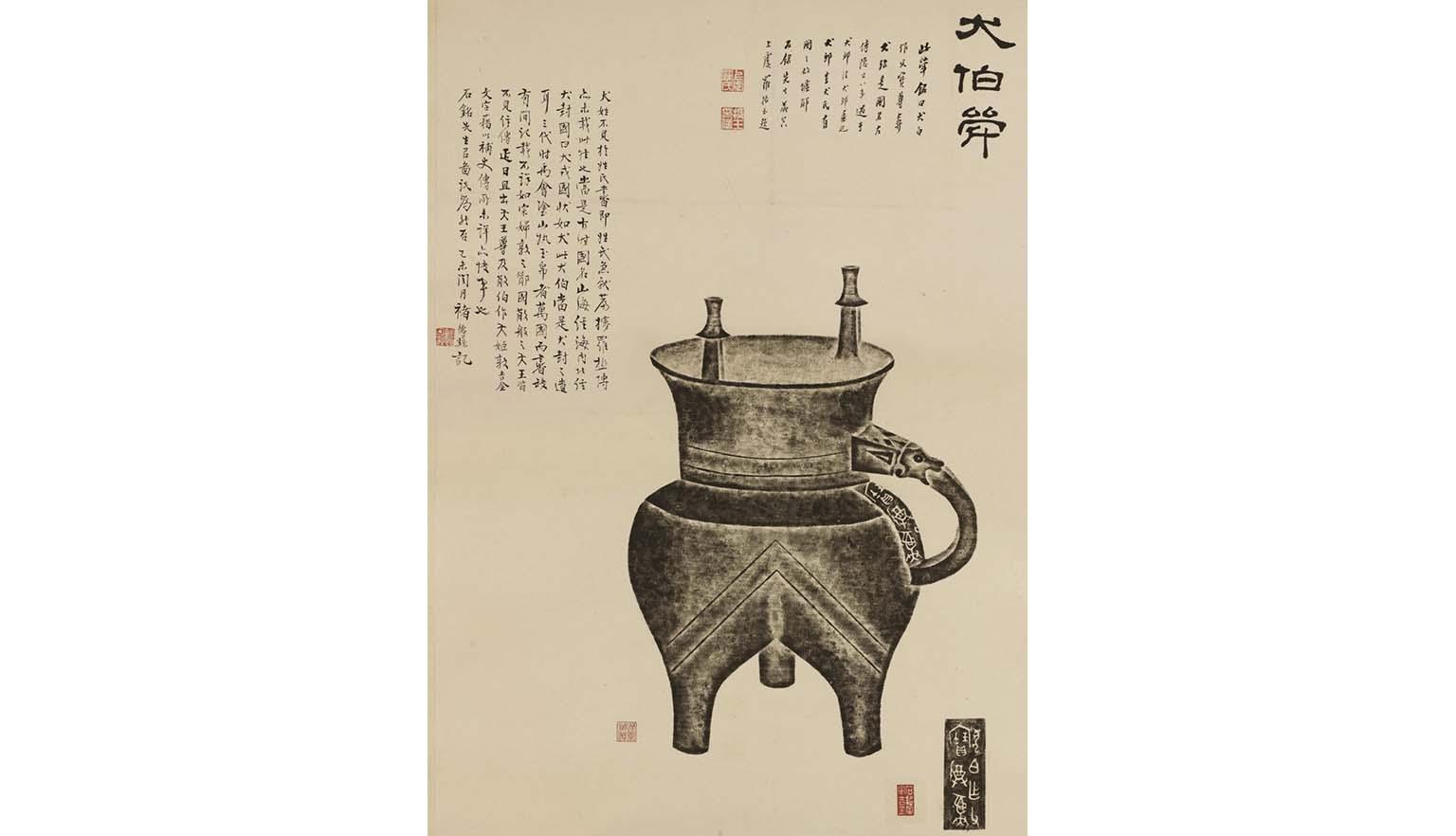

During the Qing dynasty, scholars began to re-examine China’s cultural heritage by returning to original sources. This included studying inscriptions on bronze vessels and mirrors from earlier eras. These inscriptions often recorded the reason for the object’s production—such as to mark a victory or reward good service—and were considered links to the past in a culture that valued the written word.

Because the original objects were heavy and not easily shared, rubbings were taken from their surfaces. These preserved both the texture and form of the object and allowed scholars to study the inscriptions closely. A rubbing mounted on paper or silk could also include a collector’s notes.

It became accepted that rubbings were more accurate than hand copies. Skilled artisans were required to produce high-quality work.

A new technique called composite rubbing emerged in the late Qing era. This method aimed to capture the three-dimensional nature of a vessel on a two-dimensional surface. It involved:

- taking many measurements

- using numerous stencils

- shifting rubbing paper up to 200 times

- manipulating paper and ink to reproduce depth and perspective

This was a highly creative process, with different artists able to produce distinct rubbings of the same object.

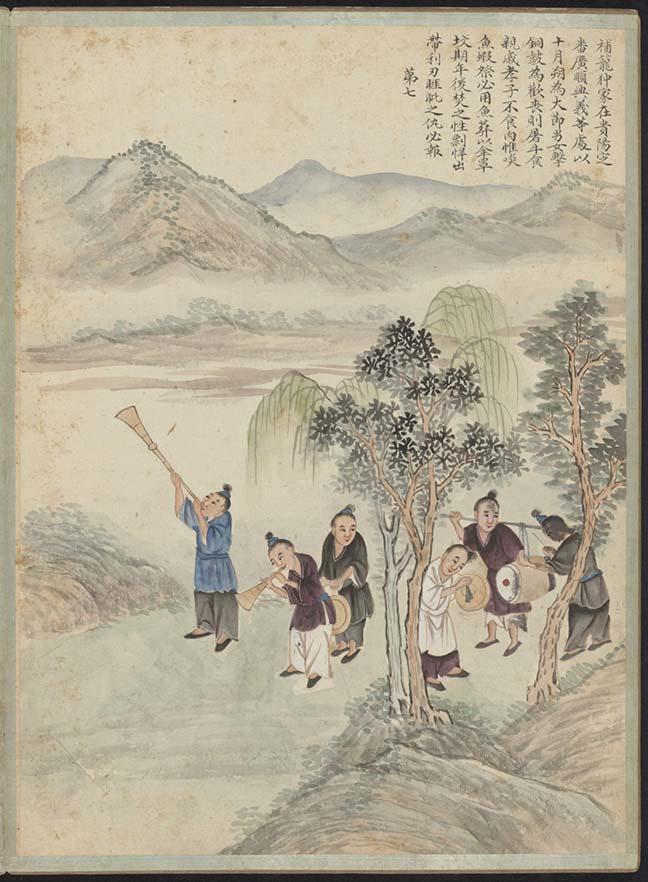

Painting minority cultures

The border regions of Yunnan, Sichuan and Guizhou were home to diverse communities that had long resisted central rule. The Qing dynasty adopted earlier strategies of governance, including forming alliances and using military force. They also initially took a positive interest in learning about these groups.

One result was the so-called Miao Albums, collections of illustrations that portrayed the customs of ethnic groups in these border regions. Originally created for administrative purposes in the early Qing period, they were later marketed more widely. By the 19th century, they were commonly available in cities such as Beijing and Shanghai.

These richly detailed images offer insights into the lives of ethnic minorities during the Qing dynasty, though their accuracy must be critically assessed.

Zhongguo Xi nan di qu shao shu min zu sheng huo xi su hua ce] [Paintings of life and customs of the minorities in the Southwest China], 1850, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-76789707

Zhongguo Xi nan di qu shao shu min zu sheng huo xi su hua ce] [Paintings of life and customs of the minorities in the Southwest China], 1850, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-76789707

Learning activities

Activity 1: Comparing painting styles

Ask students to compare painting and woodblock printing styles from Qing China and Edo Japan (1603–1868). They should present their findings visually, using Prezi, PowerPoint or similar tools.

Activity 2: Influences of Confucianism

Ask students to investigate Confucius and his influence during the Qing dynasty.

Prompt discussion:

- What was the relationship between the Qing dynasty and earlier dynasties?

- How did Confucian ideas shape this relationship, particularly views of antiquity?

Activity 3: Composite rubbings

Devise a classroom activity to explore composite rubbings. Have students choose a three-dimensional object and reproduce it on paper using crayons and different rubbing techniques.

Encourage students to:

- Reflect on the idea of ‘accuracy’ in rubbings

- Explore modern examples (such as, gravestone rubbings in family history, archaeological documentation)

Activity 4: Interpreting historical images

Use the image Paintings of life and customs of the minorities in Southwest China to prompt discussion.

Ask students:

- How reliable are paintings as historical sources?

- Were the scenes posed or influenced by the artist or audience?

- What perspectives are being represented—and which are missing?