Emperors

The Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ruled China for nearly 270 years, from 1644 to 1911. It was the last of China’s so-called conquest dynasties, governed during this period by the Manchus—an ethnic group from beyond China’s frontiers.

The early Qing court renovated its quarters in the palace, but many emperors preferred not to live within its walls, finding life there limiting and dull. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the court increasingly expanded the imperial gardens to the northwest of the capital. The Kangxi Emperor (r. 1661–1722), pleased with the improvements made during his reign, often conducted affairs of state there.

His efforts were surpassed by those of his son and grandson—the Yongzheng Emperor (r. 1722–1735) and Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735–1795)—who transformed the landscape. Artificial lakes and accommodation for the emperor’s entourage and administration spread across a large area. The gardens included design elements drawn from those south of the Yangzi River and came to reflect particular aesthetic ideals. However, maintaining them placed significant strain on court finances.

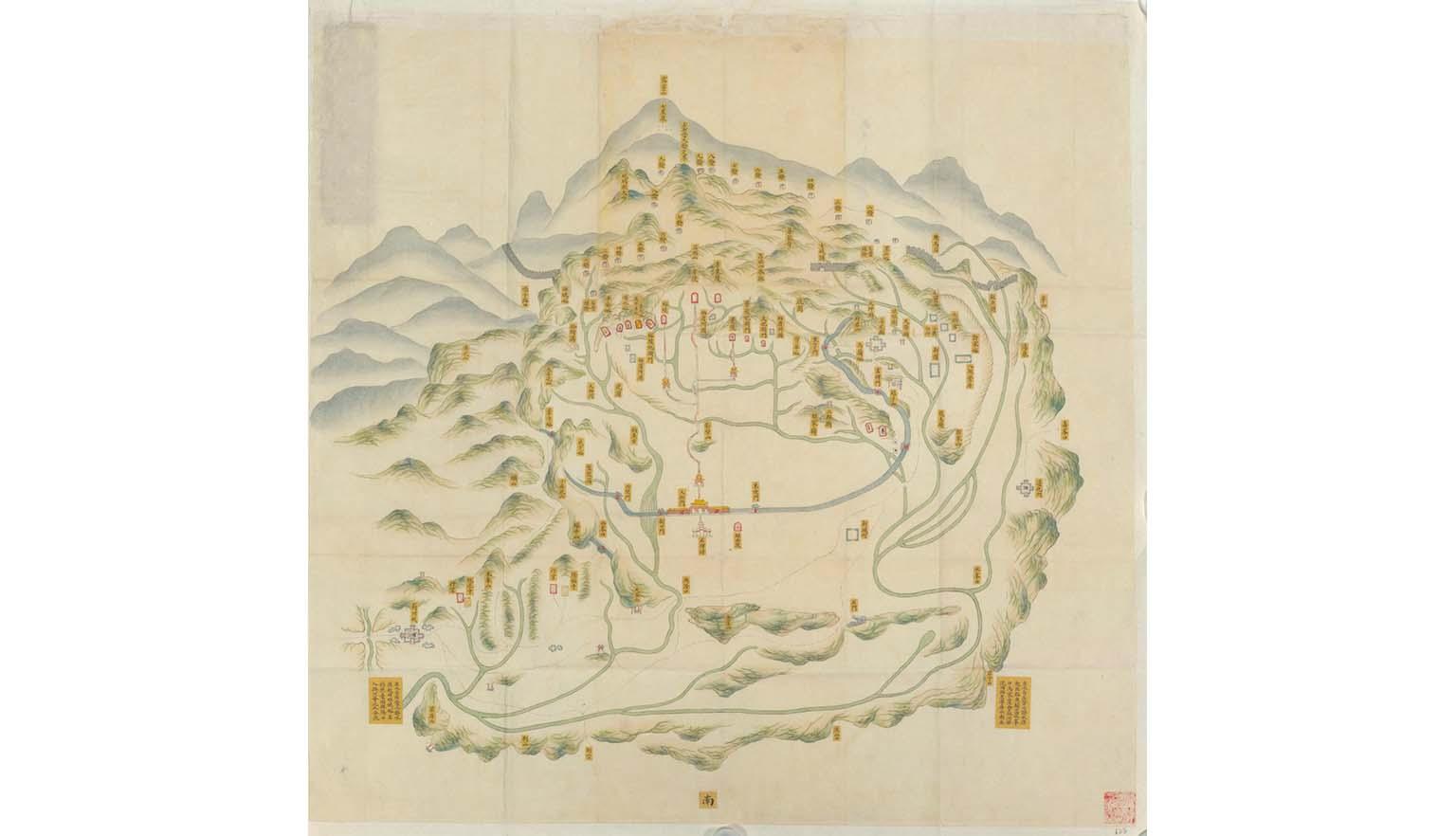

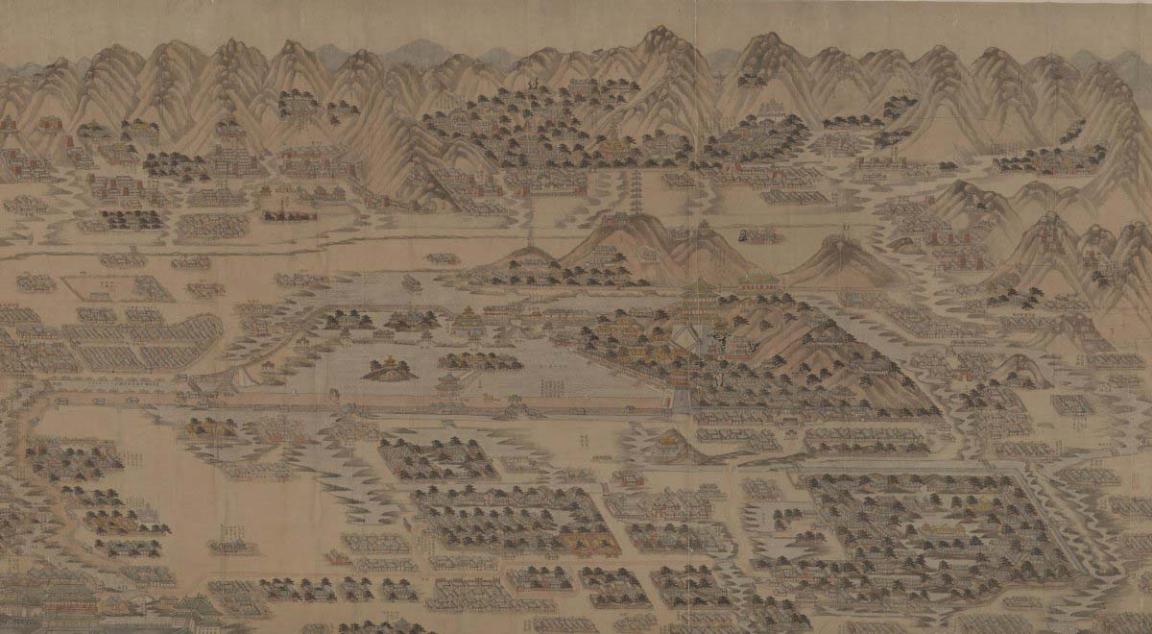

Surviving maps of the gardens date to the late Qing period, when the area was often referred to as the Five Gardens and Three Mountains. Many maps use a similar perspective, looking northwest from above Beijing. The Garden of Cultivated Harmony (Yiheyuan, now known as the Summer Palace) is located at the centre of the example shown here, with the pagoda on Longevity Hill appearing much as it does today. The Garden of Perfect Brightness (Yuanmingyuan, now known as the Old Summer Palace) is located below it.

The Five Palace Gardens 1904, National Library of China

The Five Palace Gardens 1904, National Library of China

List of Qing Emperors, 1644-1911

Ten emperors ruled during the Qing period:

- Shunzhi Emperor (1644–1661)

- Kangxi Emperor (1662–1722)

- Yongzheng Emperor (1723–1735)

- Qianlong Emperor (1736–1795)

- Jiaqing Emperor (1796–1820)

- Daoguang Emperor (1821–1850)

- Xianfeng Emperor (1851–1861)

- Tongzhi Emperor (1862–1874)

- Guangxu Emperor (1875–1908)

- Xuantong Emperor (1909–1911)

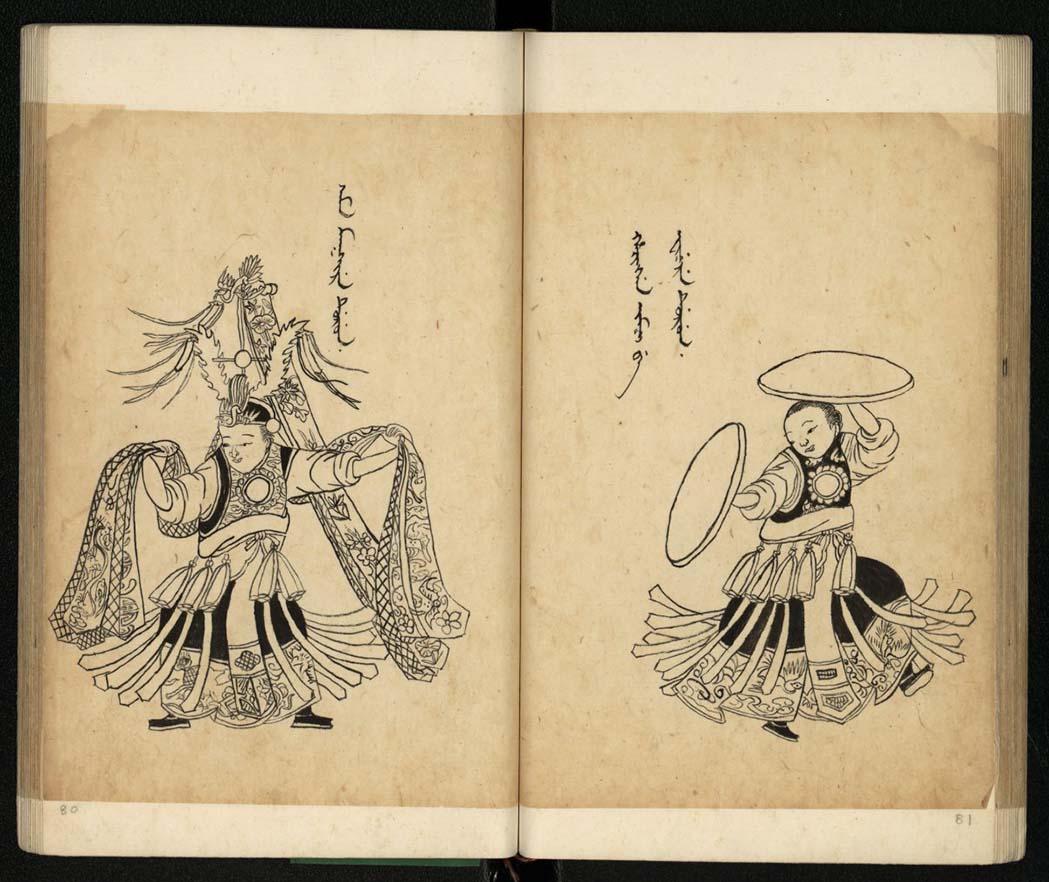

Illustrated Manchu Rituals, National Library of China

Illustrated Manchu Rituals, National Library of China

Manchu rituals and identity

The imperial family reinforced its cultural authority in the northeast through the practice of shamanic rituals at court.

Distinct from Mongolian (Tibetan Buddhist) and Chinese traditions, Manchu shamanism helped promote a unique cultural identity. Shamans traditionally connected their communities with spirits and ancestors. They entered the spirit world through dance and chant, serving as healers and diviners.

At court, however, these rituals took on a new form. The oral tradition was replaced with a fixed written code. Only Manchu people were permitted to view these rituals—and even the emperors rarely attended.

The Qing rulers sought to demonstrate their legitimacy within the Chinese tradition while maintaining a separate Manchu identity. Both aims were crucial to their ongoing rule. The court sometimes took steps to ensure Manchus maintained their martial skills and language, which were considered vital to being Manchu.

Court dress strictly differentiated social ranks and reinforced Manchu culture. It was during the Qing period that men were required to wear a queue or pigtail—a hairstyle foreign to most Han Chinese people.

Architecture and ceremony

The Lei family produced generations of imperial architects, beginning in the 17th century. They oversaw the construction of palaces, gardens and tombs. The surviving Yangshi Lei Archives offer insight into the design of many iconic sites around Beijing.

The Lei architects also helped organise imperial spectacles, including birthdays and weddings. Plans for tents from the late Qing period show the grandeur of these celebrations.

The emperors’ final resting places were divided between two sites. The first two emperors were buried northeast of Beijing, at what is now known as the Eastern Tombs. The third emperor was buried southwest of the city, creating what is now the Western Tombs.

Although the Great Wall dominates popular imagination of Chinese architecture, Qing emperors invested in a wide range of buildings, including palaces and temples.

Learning activities

Activity 1: Ritual and dress

Have students conduct an internet research task at home, investigating ritual and dress during the Qing period. They should be prepared to discuss these topics in the next lesson.

Activity 2: Qing architecture

Assign each group of two or three students a Qing emperor. Have them investigate:

- What did this emperor build, modify or renovate?

- Why?

- Can any of these architectural achievements still be seen today?

- What are the features of Qing architecture?

- Did Qing architecture change over time? Why?