Territory

The Qing dynasty

The Qing unified a diverse population under a relatively small administration. At its peak, it was one of the richest and most powerful states in the world.

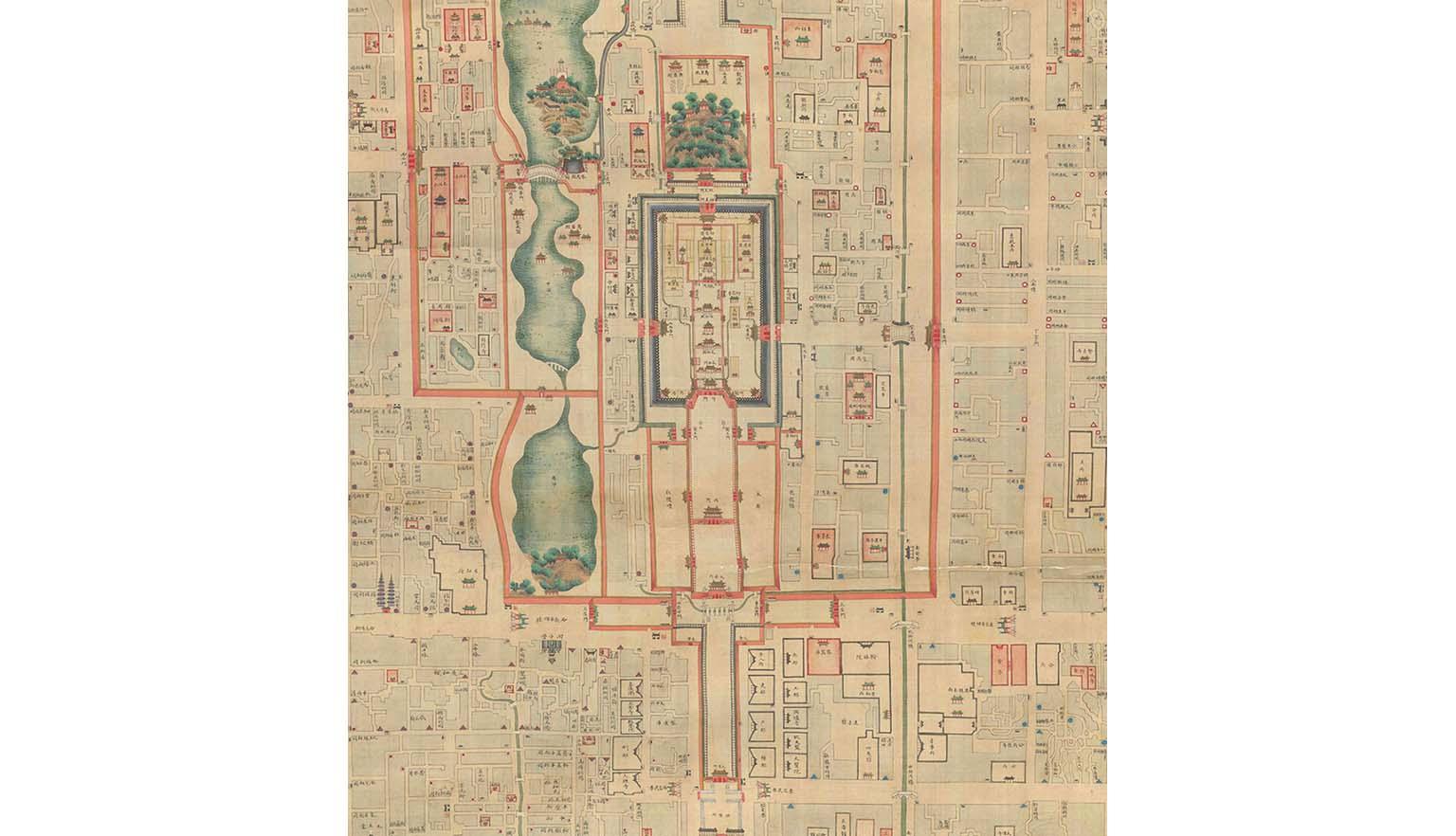

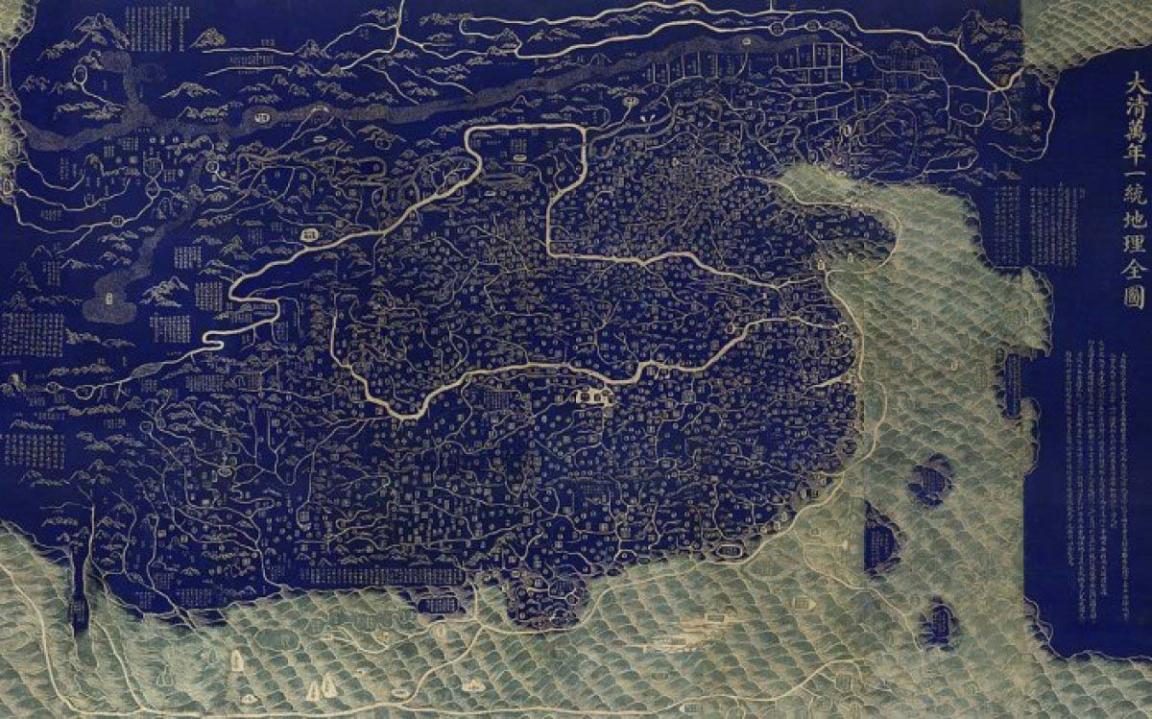

One of the most impressive representations of Qing authority is the Complete map of the everlasting unity of the Great Qing. This administrative map identifies provincial and local government centres. The Manchu homelands northeast of Beijing and parts of Mongolia are divided by straight lines, showing how the empire used Banners and leagues for military and administrative control.

The map served as a cultural tool to assert the Qing court’s power over its vast territory. It exists as a rubbing across 8 scrolls.

After Huang Qianren (1694–1771), Complete Map of the Everlasting Unity of the Great Qing (Da Qing wannian yitong dili quantu), Jiaqing period (1796–1820), National Library of China

After Huang Qianren (1694–1771), Complete Map of the Everlasting Unity of the Great Qing (Da Qing wannian yitong dili quantu), Jiaqing period (1796–1820), National Library of China

The Manchu court ruled China proper for nearly three centuries and also governed parts of Mongolia and the Islamic northwest. Qing administrators recognised the importance of local customs and traditions in managing this culturally diverse region. The dynasty also engaged diplomatically and politically with Tibet.

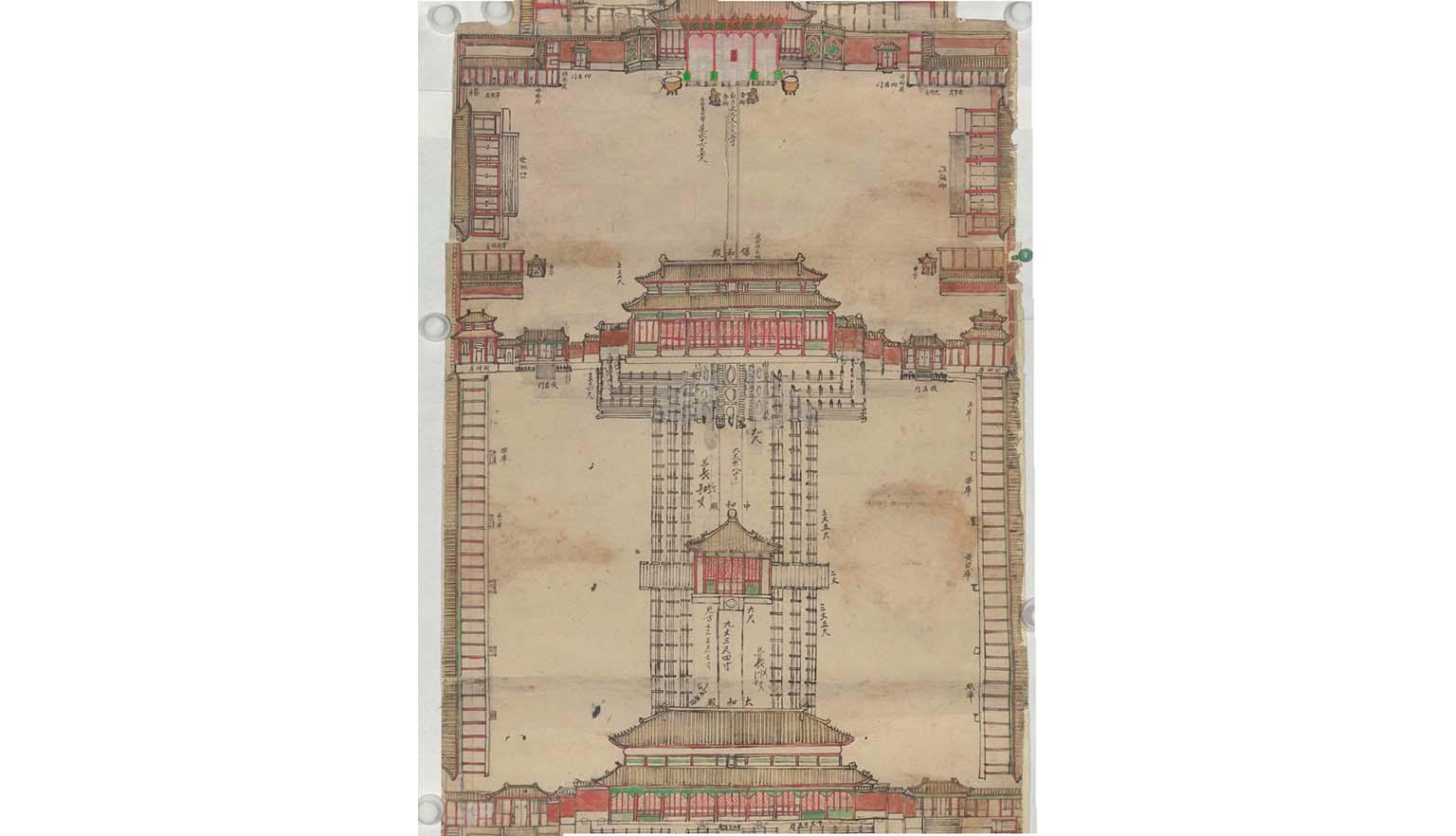

The Forbidden City

Beijing has not always been China’s capital. Over the past 2,000 years, it has shifted multiple times. In the early 15th century, the Yongle Emperor (1403–1424) of the Ming dynasty moved the capital from Nanjing to Beijing. Construction of the original walled palace—later known as the Forbidden City—began in 1416 and finished in 1420.

Early emperors, accustomed to travelling across their territories, often preferred to stay in garden palaces northwest of Beijing. These included the mountain resort at Chengde—sometimes called ‘Xanadu’ in the West—and the nearby Mulan hunting grounds.

The design of the Forbidden City reflects the Chinese belief that social order depends on clear divisions. Entry was through the Meridian Gate, which stood 35 metres tall. During the Qing period, no other building in Beijing could be taller. The gate was named after the main longitude on the early Chinese compass and aligned with a north–south axis. The palace buildings were arranged symmetrically along this axis.

The southern portion of the palace was a public space used for ceremonies. Its key buildings—the Hall of Supreme Harmony, the Hall of Preserving Harmony and the Hall of Heavenly Purity—reflect the imperial ideal of cosmic order.

These architectural designs come from the archives of the Lei family, who served as imperial architects for generations. Their records, held by the National Library of China, are inscribed on the UNESCO Memory of the World Register.

The sites themselves—the Imperial Palaces of the Qing Dynasty—are on the UNESCO World Heritage List. They meet criteria (i) to (iv):

- Represent a masterpiece of human creative genius

- Show an important interchange of human values across time or region

- Bear exceptional testimony to a living or lost civilisation

- Be an outstanding example of a building or architectural ensemble that illustrates a key stage in human history

Mapping China

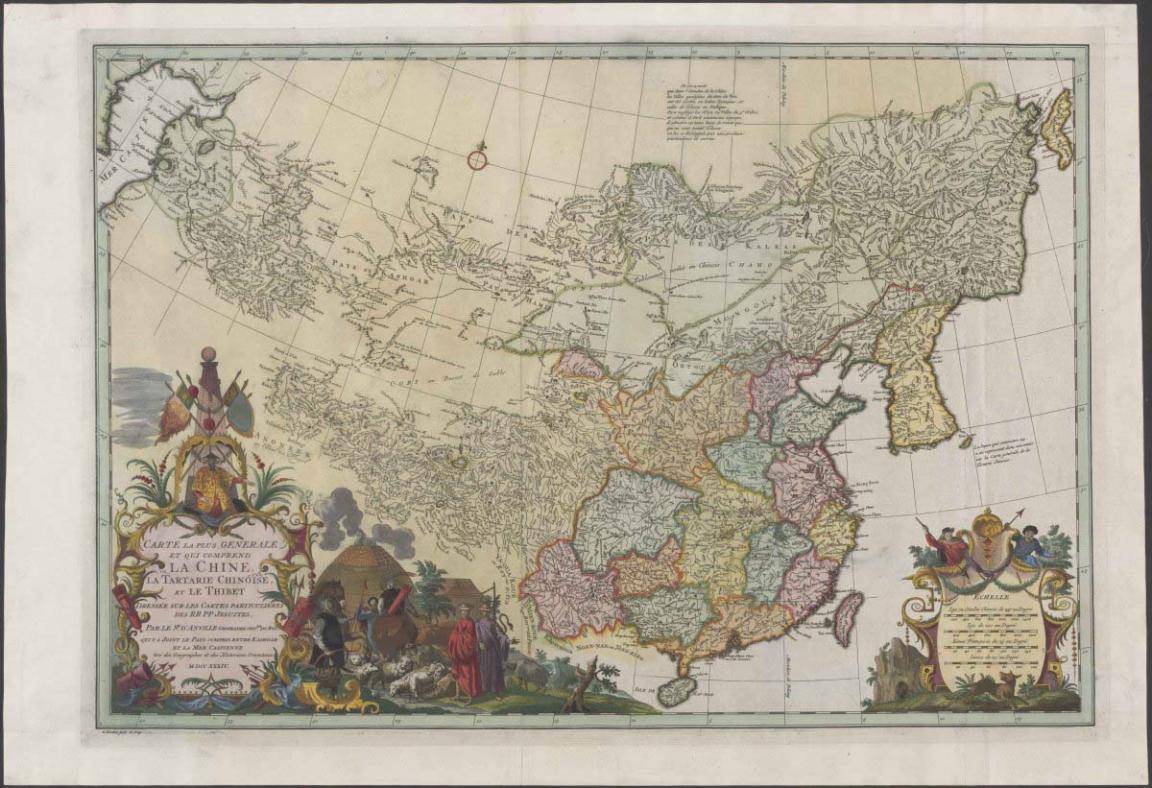

This map of China was drawn by French cartographer Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville (1697–1782). It was published in The Hague in 1737 in Nouvel atlas de la Chine. It is one of four general maps in the volume—covering China, Tibet, Tartary (Manchuria and parts of inner Asia), and a composite of all three.

D’Anville’s maps became the standard Western source on Chinese geography throughout the 19th century. He aimed to reform European cartography by avoiding blind copying and including only verified data—even if that meant leaving parts of the map blank.

He based this map on surveys conducted by the Qing empire between 1708 and 1718, during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor. The data came from maps sent to Europe and from European sources, including French Jesuit missionaries who had been sent to China by Louis XIV in 1685 to gather geographical knowledge.

Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d'Anville & Henri Scheurleer & Gerardus Condet, Carte la plus generale et qui comprend la Chine, la Tartarie chinoise, et le Thibet, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-232293356

Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d'Anville & Henri Scheurleer & Gerardus Condet, Carte la plus generale et qui comprend la Chine, la Tartarie chinoise, et le Thibet, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-232293356

Learning activities

Activity 1: Governing an empire

Have students investigate the strategies used by the Manchu to manage the broader empire. Focus areas could include:

- language

- religion

- administrative structure

Activity 2: World Heritage

Have students assess the significance of the Imperial Palaces of the Qing Dynasty. Use the four UNESCO World Heritage selection criteria to guide their evaluation.

Activity 3: Mapping the empire

Explore these questions using the Think–Pair–Share method:

- Who were the Jesuits?

- Why did Louis XIV send missionaries to China?

- What were the goals of missionaries like:

- Louis Le Comte (1655–1728)

- Jean de Fontaney (1643–1710)

- Jean-François Gerbillon (1654–1707)

- Claude de Visdelou (1656–1737)

- Joachim Bouvet (1656–1730)

- What was France’s interest in China at the end of the 17th century?

- How does this map reflect European knowledge and understanding of China in the 18th century?