Performing arts

Beginnings

Indigenous performance has been a part of this continent for thousands of years. While often connected to ceremony, song and dance remain vital to First Nations cultures today—both to celebrate tradition and explore new musical styles. Dancing and music have long been a way to share stories of ancestors and creation.

European theatrical traditions arrived with the First Fleet in 1788. The first play performed in Australia was The Recruiting Officer by George Farquhar, staged by convicts in 1789.

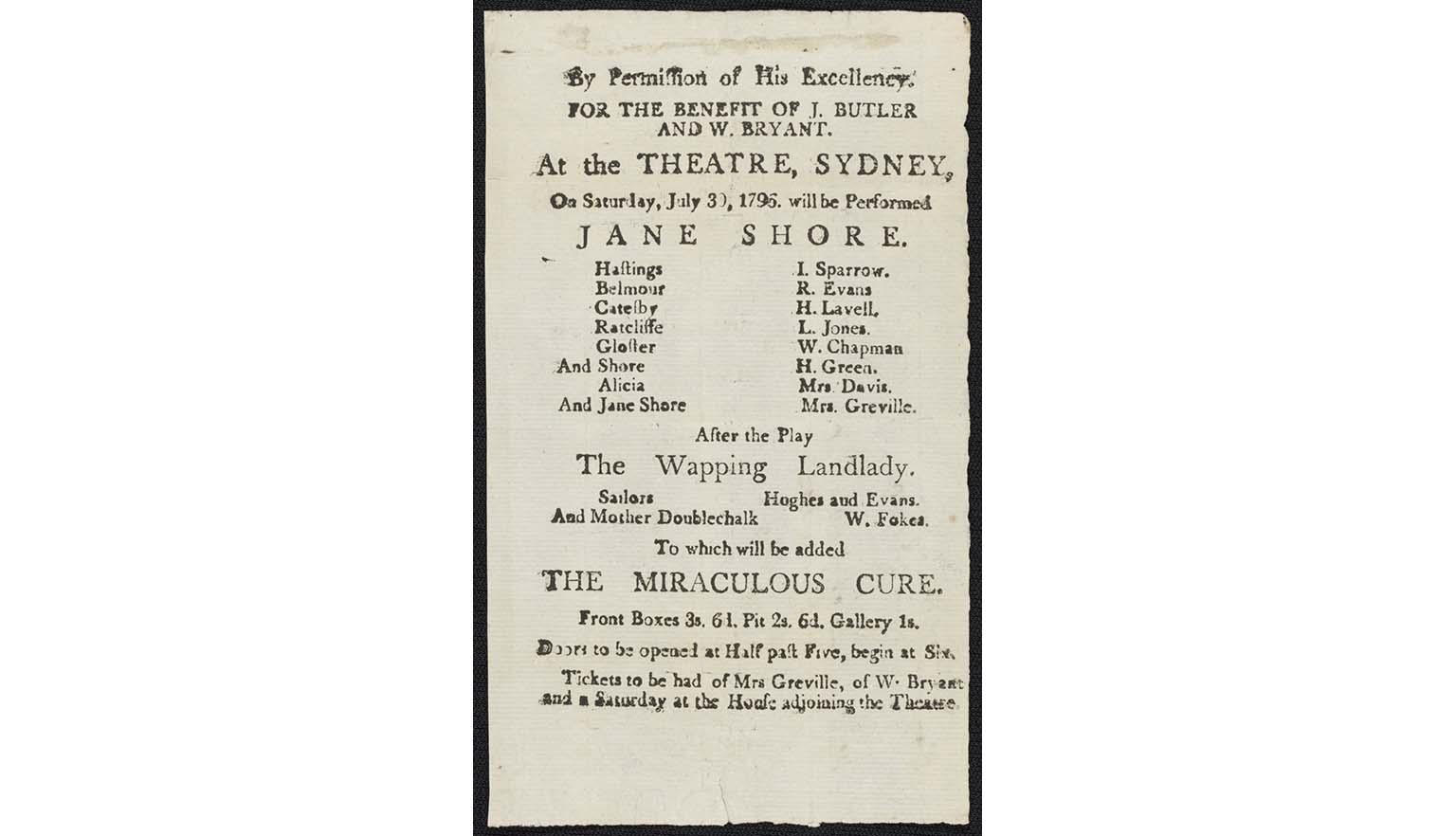

Sydney’s first theatre is believed to have opened in 1796, managed by former convict Robert Sidaway. Its exact location is still debated. Governor John Hunter viewed the theatre as a corrupting influence and closed it in 1798. Although it reopened briefly in 1800, it closed soon after. Convict theatre performances continued across the colony until around 1840.

The earliest known document printed in Australia is a playbill advertising a night of performances at this early theatre. The event featured a tragedy, a comedy and a dance—all organised and performed by convicts.

The playbill was discovered in a scrapbook held by Library and Archives Canada and was later returned to Australia as a gift to the Australian people.

Learn more in the Digital Classroom module An early arts scene.

Visiting ladies

From the gold rush era onwards, several international female performers toured Australia, leaving a lasting impact on its entertainment scene.

Lola Montez became famous for her Spider Dance, which shocked and delighted audiences on the goldfields. Her popularity endured—so much so that in 1958, the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust staged a musical about her life.

In 1891, acclaimed French actress Sarah Bernhardt toured Australia. Crowds flocked to see her in La Dame aux Camélias (Camille, or The Lady of the Camellias) by Alexandre Dumas.

Portrait of Lola Montez ca. 1855, 1926, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135569180

Portrait of Lola Montez ca. 1855, 1926, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135569180

The circus

Circuses were among the earliest popular entertainment forms in Australia. For more than a century, travelling shows were a major attraction, especially in regional areas.

As rural populations declined and new entertainment options like cinemas and television emerged, traditional circuses became less common. Public concern about animal welfare also led to fewer animals being used in performances.

From the 1960s to the 1990s, contemporary circuses such as Cirque du Soleil became popular. These performances focused on human acrobatics, movement and storytelling. Australia has its own celebrated troupes, including the Flying Fruit Fly Circus and Circus Oz.

Loui Seselja, Flying Fruit Fly Circus trapeze performance at the opening ceremony of the National Museum of Australia, Canberra, 11 March 2001, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-146590891

Loui Seselja, Flying Fruit Fly Circus trapeze performance at the opening ceremony of the National Museum of Australia, Canberra, 11 March 2001, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-146590891

Magicians

Magicians also captivated Australian audiences. Harry Houdini visited in 1910 to great acclaim.

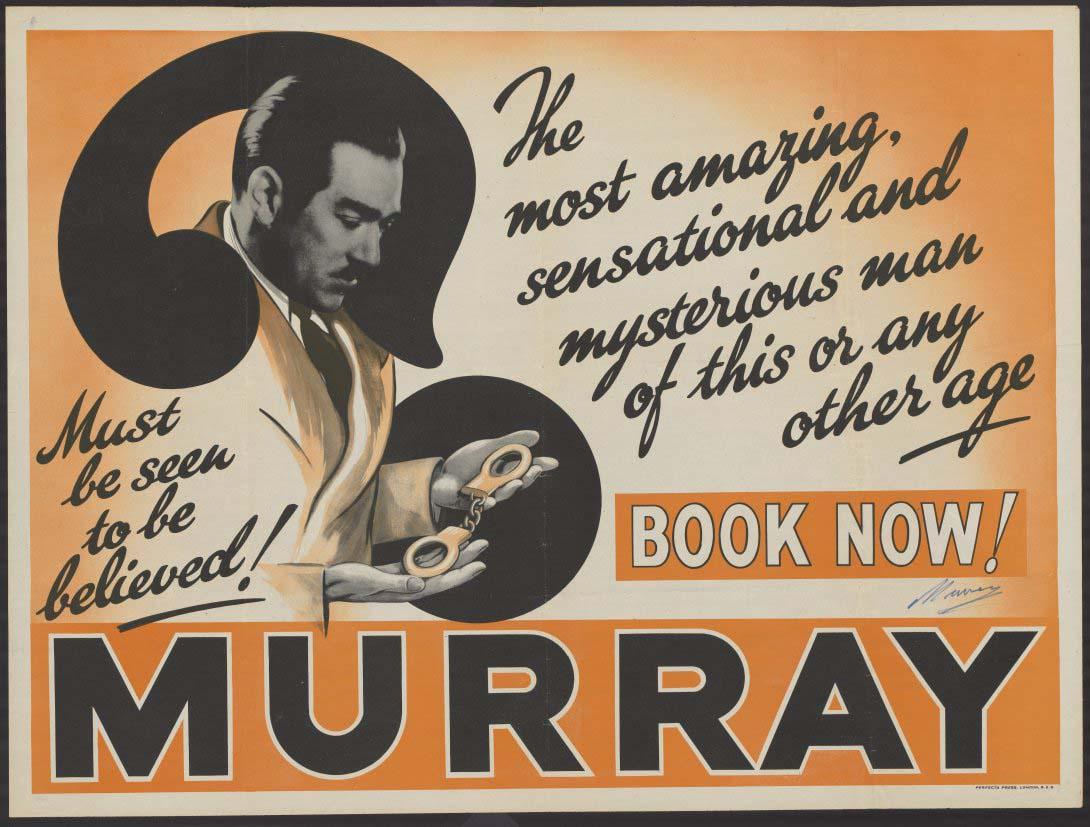

Australia’s own Norman Murray Walters—known professionally as Murray the Escapologist—became a global sensation with his daring escape acts. Some credit him with coining the word 'escapology'.

Murray the Most Amazing, Sensational and Mysterious Man of This or Any Other Age ... London: Perfecta Press, between 1920 and 1929, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-2632287217

Murray the Most Amazing, Sensational and Mysterious Man of This or Any Other Age ... London: Perfecta Press, between 1920 and 1929, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-2632287217

Vaudeville and variety theatre

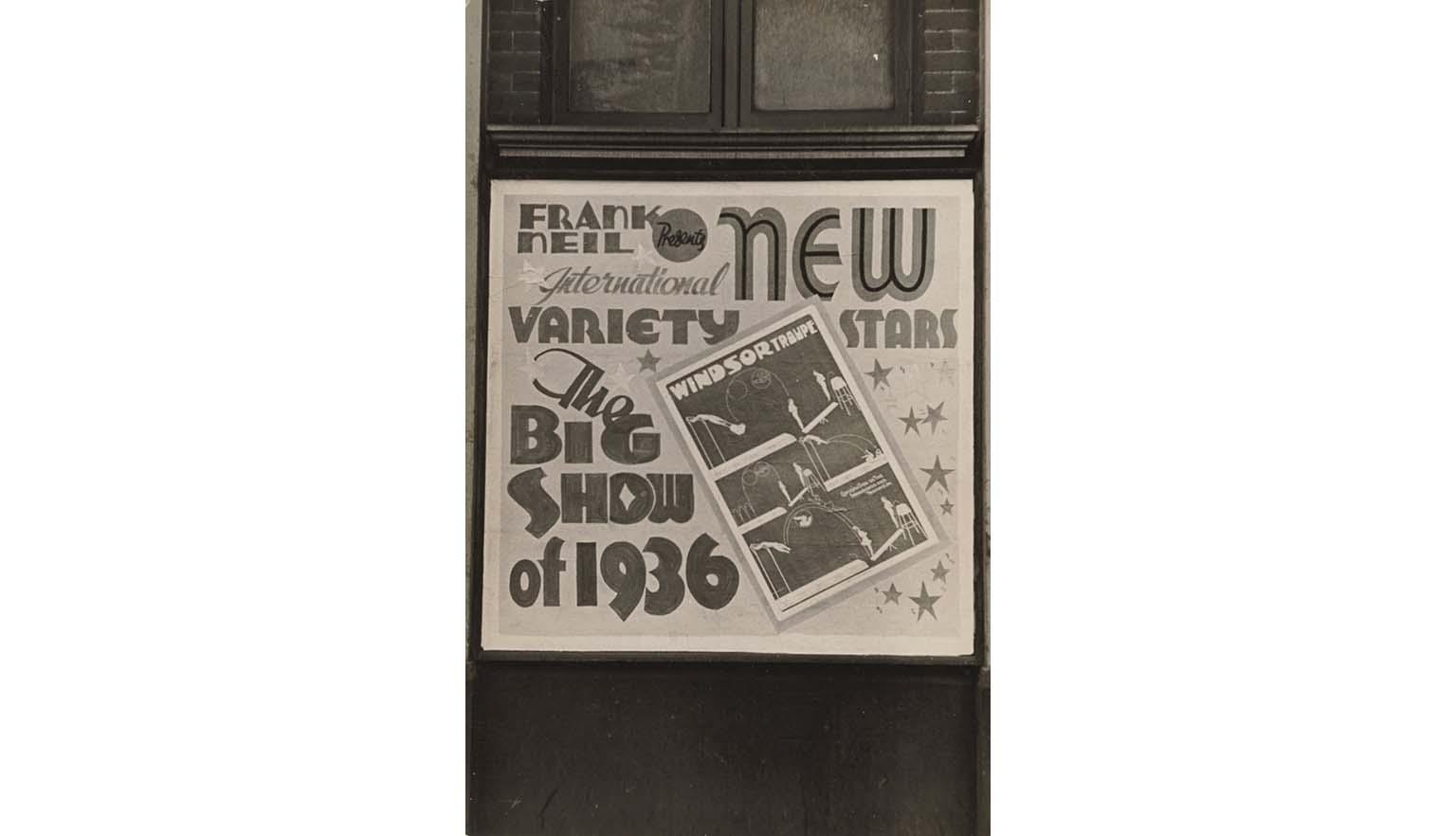

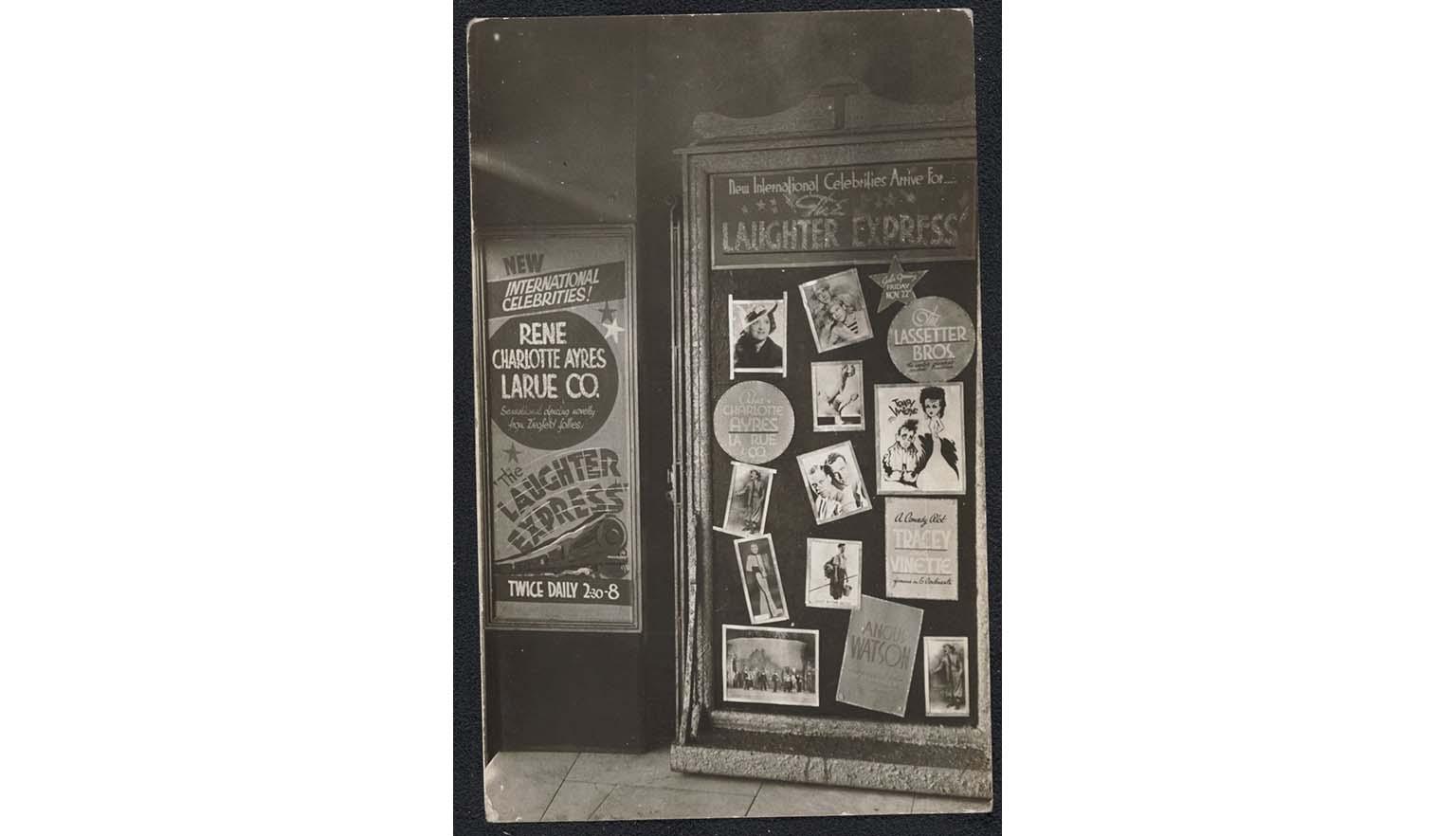

Vaudeville and variety theatre arrived in Australia in the 1890s. Tivoli theatres—founded by comedian Harry Rickards and later managed by J.C. Williamson—were especially popular.

These venues showcased singers, dancers, acrobats, comedians and ventriloquists. Before television, they were a major source of public entertainment. As TV ownership grew in the mid-20th century, interest in variety theatre declined.

Australian born performer, Paulina Clarissa Molony, professionally known by the stage name Saharet, caused an international sensation as a vaudeville dancer and actress.

She was born in Melbourne or Ballarat, Victoria, in the late 1870s. Her mother was of part-Chinese heritage. Her family migrated to the United States when Saharet was young. Saharet performed in the US, Paris and at the Wintergarten in Berlin. In 1913, she returned to Australia. Newspapers in Australia eagerly kept track of her career.

Despite the geographic isolation of Australia, Australian culture has been influenced by a range of other cultures across the globe. It was connected to the wider world through overseas touring companies and performers, and by Australians performing overseas.

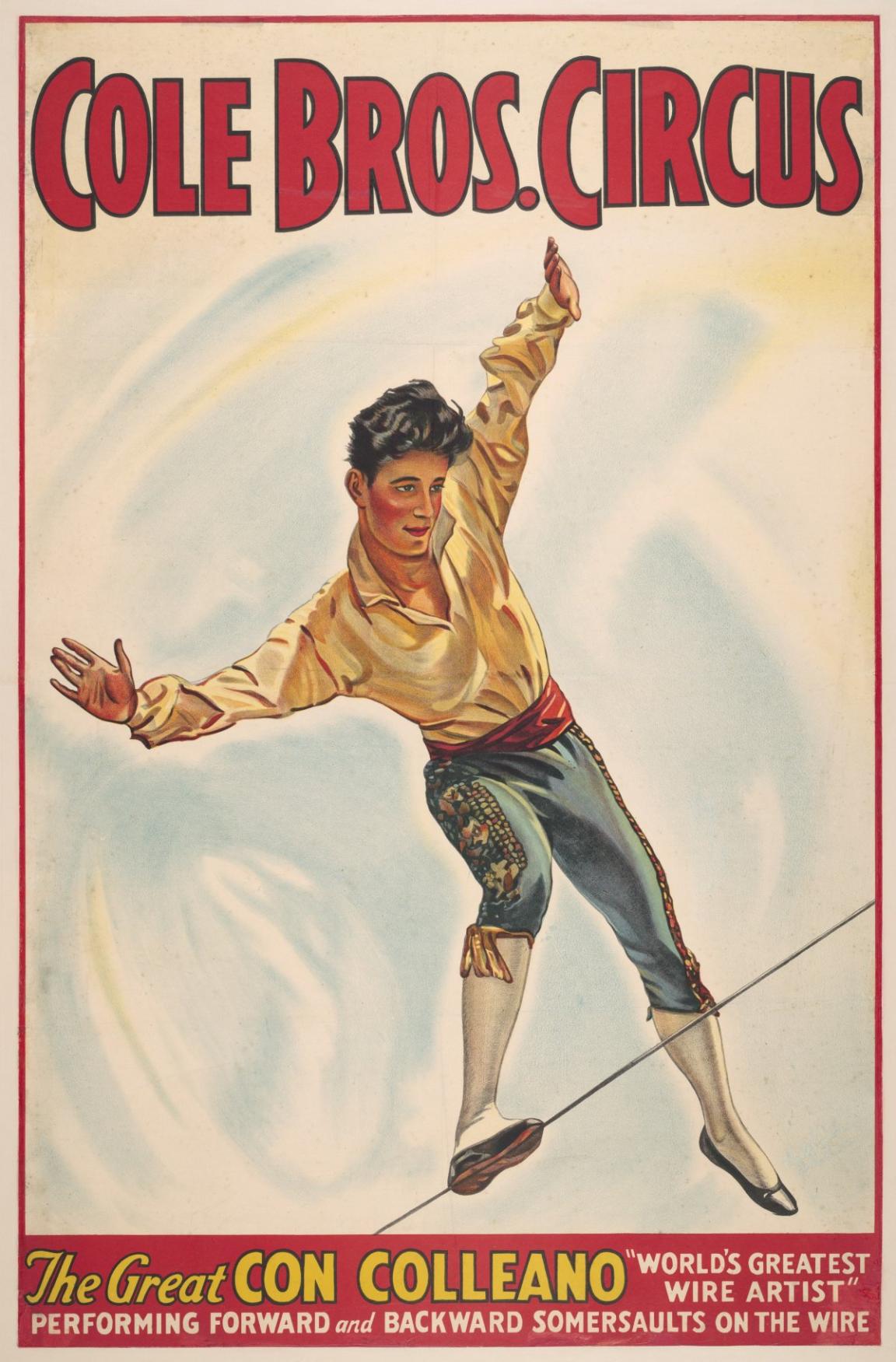

Con Colleano was an Aboriginal circus performer. He also had African heritage and later adopted a Spanish toreador persona in his performances. In 2004 the Albury-based Flying Fruit Fly Circus produced Skipping on Stars, a show about Colleano’s extraordinary life.

Cole Bros. Circus: the Great Con Colleano “World’s Greatest Wire Artist” Performing Forward and Backward Somersaults on the Wire, 1945, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136767748

Cole Bros. Circus: the Great Con Colleano “World’s Greatest Wire Artist” Performing Forward and Backward Somersaults on the Wire, 1945, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136767748

Entrepreneurs

The growth of performing arts in Australia was supported by passionate and well-funded entrepreneurs in the 19th century.

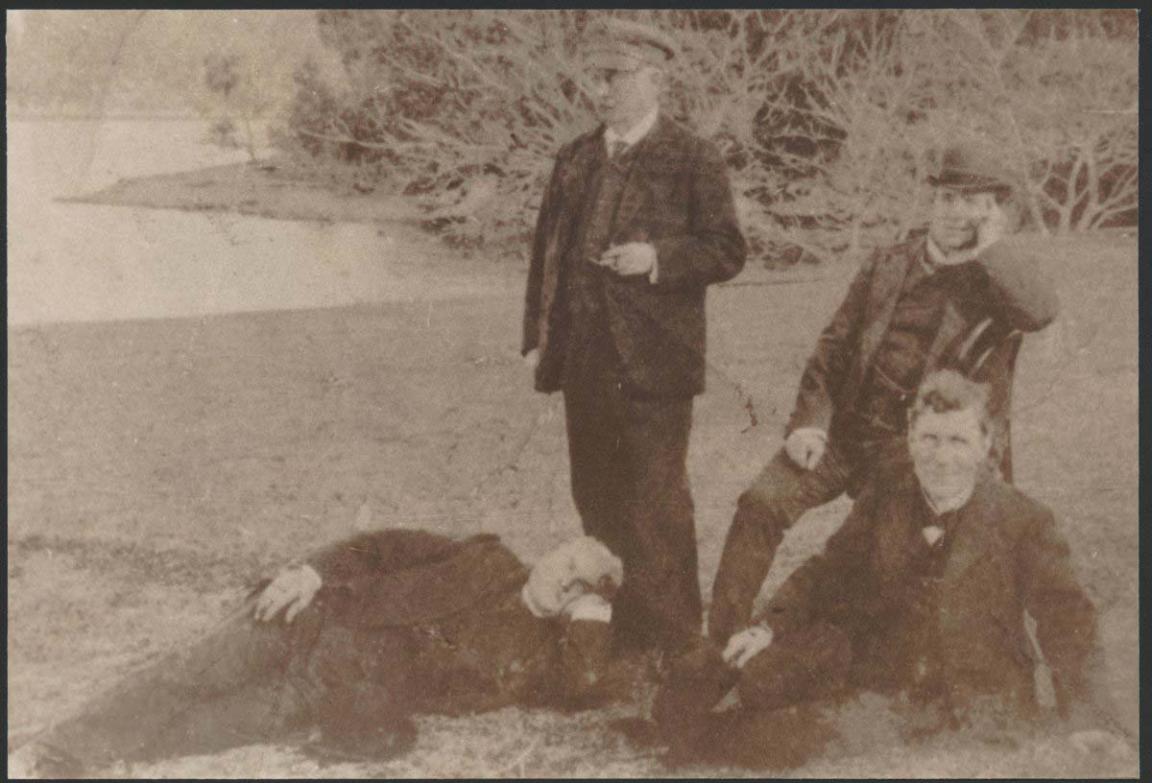

People like George Coppin, Bland Holt, J.C. Williamson, George Musgrove and Harry Rickards helped establish theatres and manage performing companies. Some were actor–managers who performed while also running productions.

Letters between performers and their managers reveal the everyday challenges of theatre life in this period.

George Rignold, J.C. Williamson, [Harry Rickards and] Bland Holt, [190-?] [picture]. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-148776529

George Rignold, J.C. Williamson, [Harry Rickards and] Bland Holt, [190-?] [picture]. nla.gov.au/nla.obj-148776529

Learning activities

Activity 1: Playbill design

Use Trove to find an article about Saharet.

- Design a playbill for one of her performances.

- Consider the emotive language used to attract an audience.

- Playbills were often printed on paper, parchment or fabric.

Activity 2: Early printing

Research early printing methods used to create playbills and posters. Try a practical activity using stamps and ink to explore early typeface and layout design.

Activity 3: Local theatres

Investigate a local theatre or performance space. Use Trove to search for past events, or explore its current programming. If possible, organise a tour to see how the venue operates.