Timeline of Australian innovations

Indigenous innovations

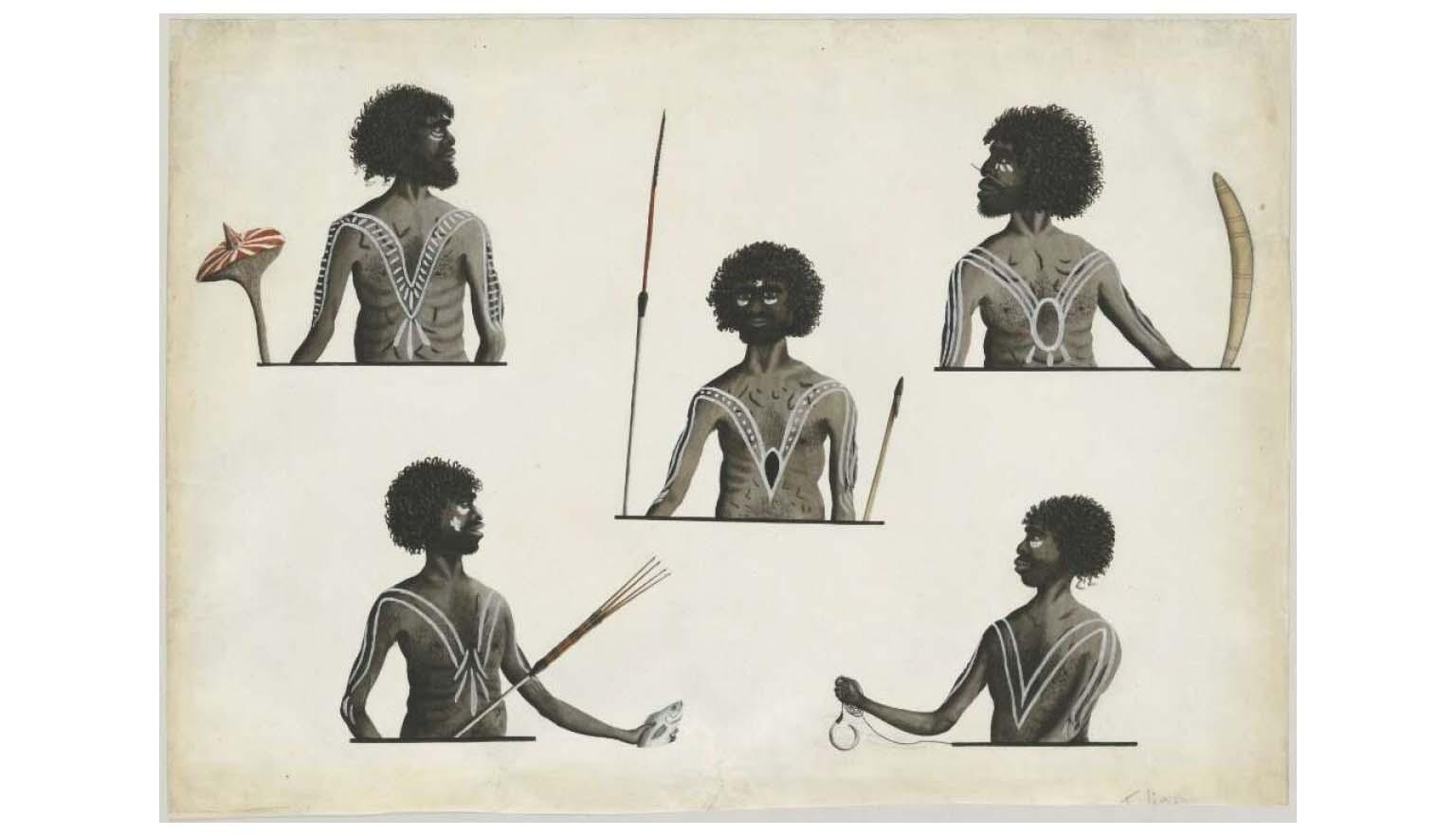

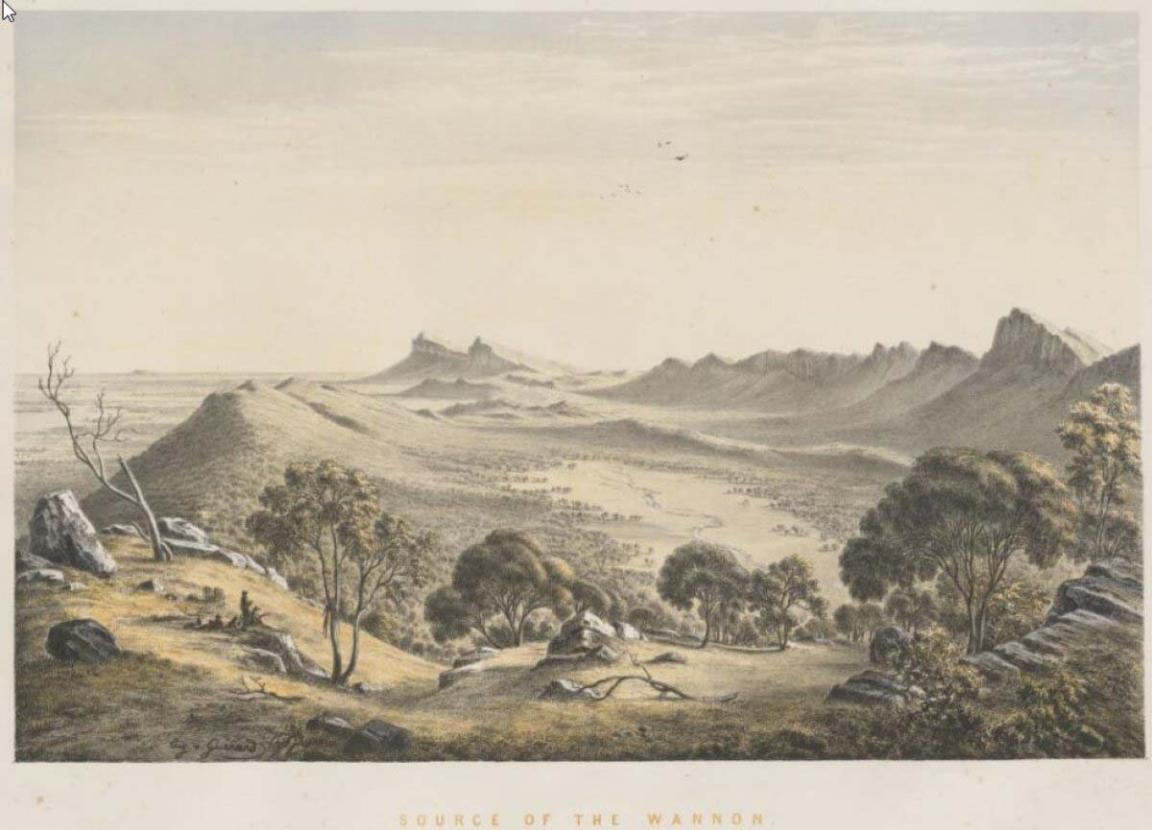

Australia is an ancient land. Some Australian fossils are around 3.5 billion years old. The history of modern humans in Australia goes back tens of thousands of years, with archaeological evidence dated to at least 65,000 years ago. Australia’s first peoples developed many objects, weapons and practices that helped them survive in the Australian landscape - an environment that was often harsh.

Eugene Von Guerard, Source of the Wannon, 1867, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135740687

Eugene Von Guerard, Source of the Wannon, 1867, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135740687

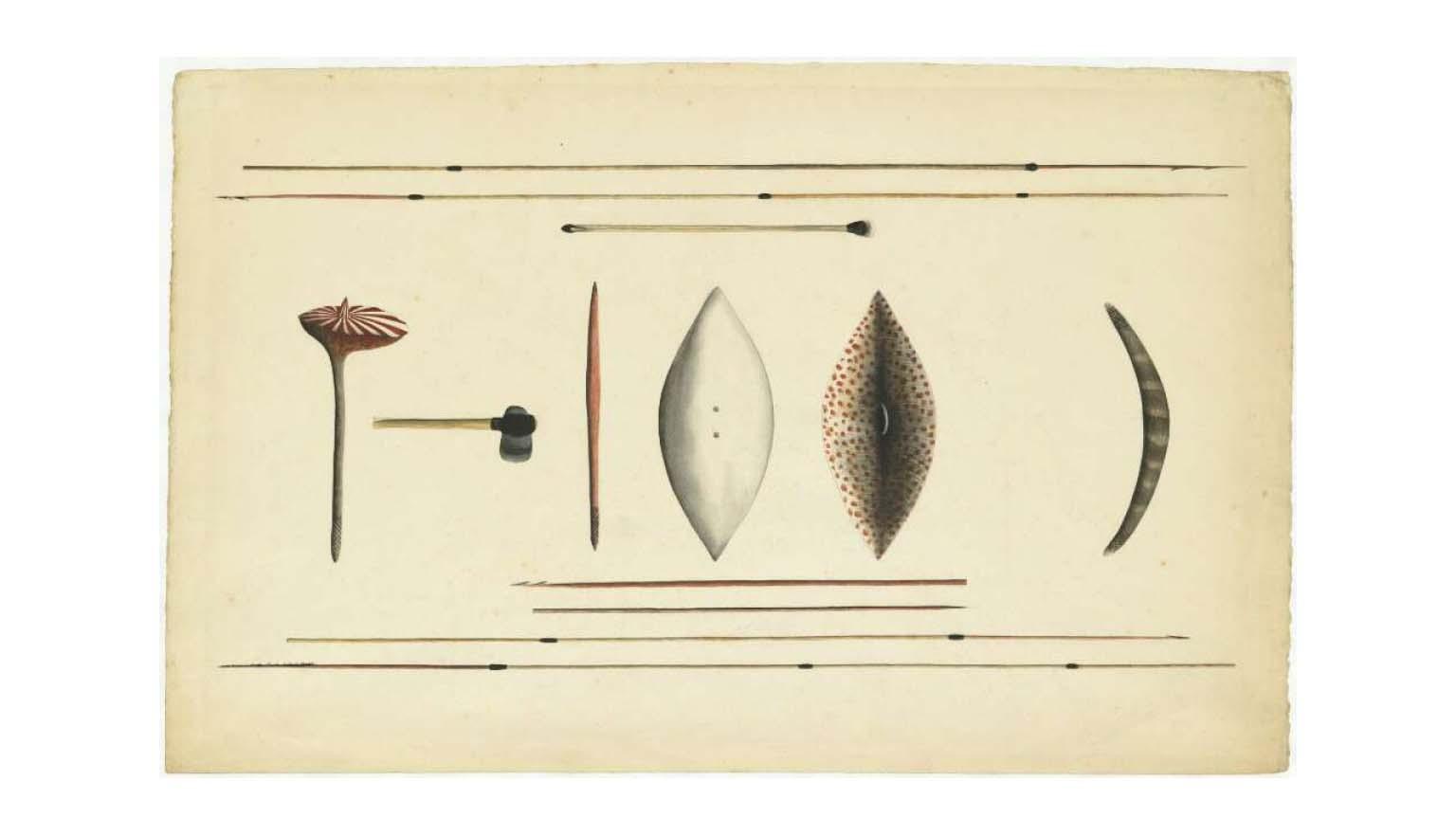

Tools for hunting and survival

The diet of the first Australians consisted of fruits, tubers and berries found throughout the Australian landscape and varied by region. They would also hunt small animals such as birds, lizards, snakes and fish, as well as big game like emus, kangaroos and wallabies. They used tools including:

- Boomerangs – made from hardwood and shaped for aerodynamic flight. Not all boomerangs were designed to return; heavier boomerangs were used to hunt and kill game.

- Spears – tipped with stone, bone or shell.

- Clubs and axes – used in hunting, fishing and combat.

- Woomeras – spear-throwers that increased throwing range and force. Some designs could also be used for cutting or digging.

Boomerangs

Hunters were skilled in the art of throwing boomerangs over long distances. Boomerangs were crafted from hardwood and sculpted in a way that made them aerodynamic. Many people think of the boomerang as an object that always returns to its thrower. However, returning boomerangs were made and used only by a select few groups - mainly as toys or for scaring birds while hunting. Heavier, longer boomerangs were used for hunting. They were not designed to return but, instead, to maim or kill their target from a distance.

Woomeras

Woomeras varied in design from group to group, but the basics were the same. A long, thin handle was carved from very hard wood and a point made of bone or stone attached to hold a spear in place. A woomera attached to the end of a spear gave the thrower more leverage. It was like an extension of the arm, meaning that the spear went further.

A spear thrown with a woomera can produce around four times the kinetic energy of a modern compound bow. Woomeras were often used as multipurpose tools; some designs were flat and shallow, with a sharp edge that could be used for cutting or digging.

Did you know? A spear thrown with a woomera can generate up to 4 times the energy of a modern compound bow.

Fire and land management

For millennia, Australian Indigenous peoples used their knowledge of the land to carefully manage the areas they frequented.

They used fire to sculpt the country in ways that would help them hunt, grow crops and prevent large-scale fires from destroying communities. They employed a complex technique called ‘firestick farming’ to create a mosaic across the land - burning some areas, leaving others and opening up wide plains next to forests. Unlike European trees, 70% of Australia’s native plants need fire to germinate. Traditional owners knew this and used fire to encourage new growth. They also knew that certain animals liked to eat fresh new grass and plants; burning areas of land to promote new growth attracted such animals, making them easier to hunt.

While communities lived off the land and knew how to exploit it, they were sure not to stay in one place for too long. This would lead to over-harvesting and damage to the ecosystem. Indigenous communities occupied different lands in a cyclical fashion to look after the land and country.

Joseph Lycett, Aborigines using fire to hunt kangaroos, 1817, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-138501179

Joseph Lycett, Aborigines using fire to hunt kangaroos, 1817, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-138501179

Colonial Australia (1788–1900)

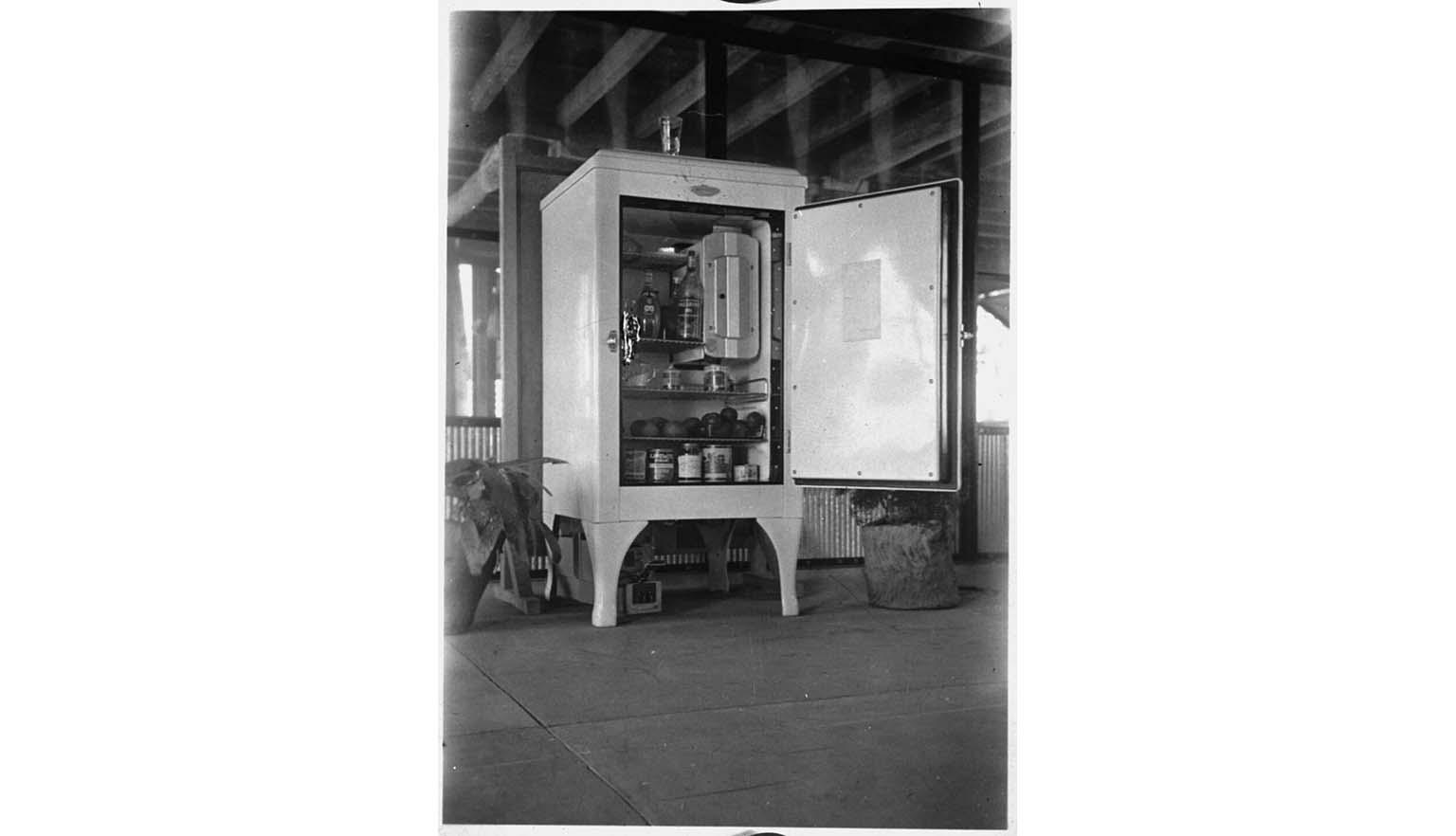

1850: Refrigeration

In the mid- to late eighteenth century, Australian agricultural output was thriving. In Great Britain, however, poor harvests and crop disease led to food shortages and riots in major cities. It wasn’t possible to ship meat or fresh produce back to Europe from Australia; with no way of keeping it cold, the food would spoil as the ships sailed through the tropics.

Samuel White Sweet, Port Parade [sailing ships on quayside with timber and other cargo, rail wagons], 1869, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-144225735

Samuel White Sweet, Port Parade [sailing ships on quayside with timber and other cargo, rail wagons], 1869, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-144225735

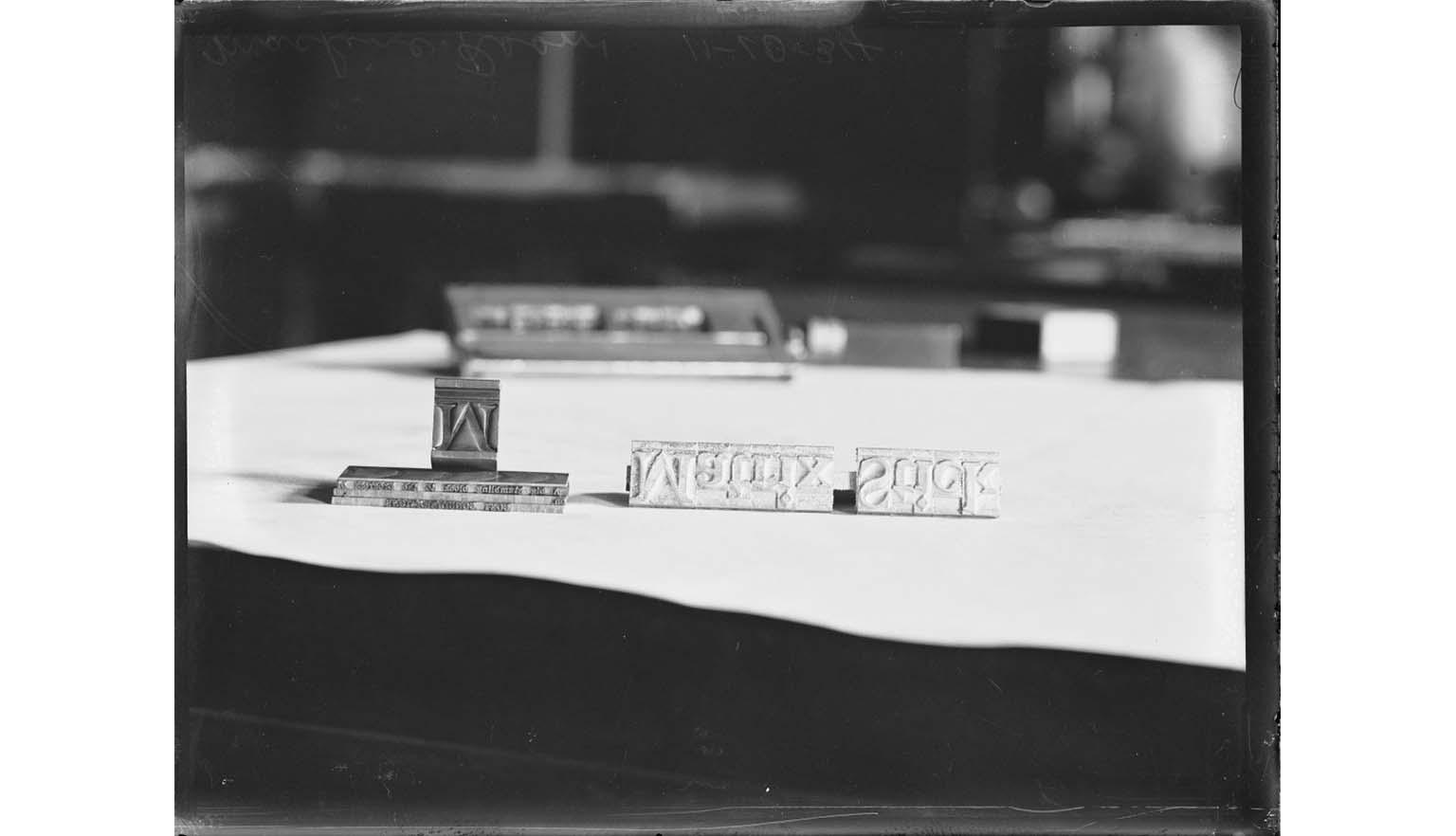

The transportation of fresh food was not possible until James Harrison, a printer from Melbourne, accidentally discovered a way to artificially cool metal while he was cleaning his printing press with ether. As the chemical evaporated, it cooled the metal.

Inspired by this, Harrison created a simple machine that pumped ether through metal coils, cooling them and, in turn, cooling their surroundings. In 1850, Harrison set up an ice factory in Geelong, Victoria, and built a refrigeration machine that produced 3 tonnes of ice per day.

In 1873, Harrison spent his own money on an experiment to send meat from Australia to England. He installed a cooling system on the ship Norfolk and filled it with 20 tonnes of beef and mutton. Unfortunately, the machinery was inadequate and the meat spoiled long before it reached England. The experiment failed and Harrison went bankrupt. However, his experiment and ideas inspired other inventors and, in 1879, the first successful shipment of refrigerated meat arrived in England. This opened up enormous export possibilities for Australia.

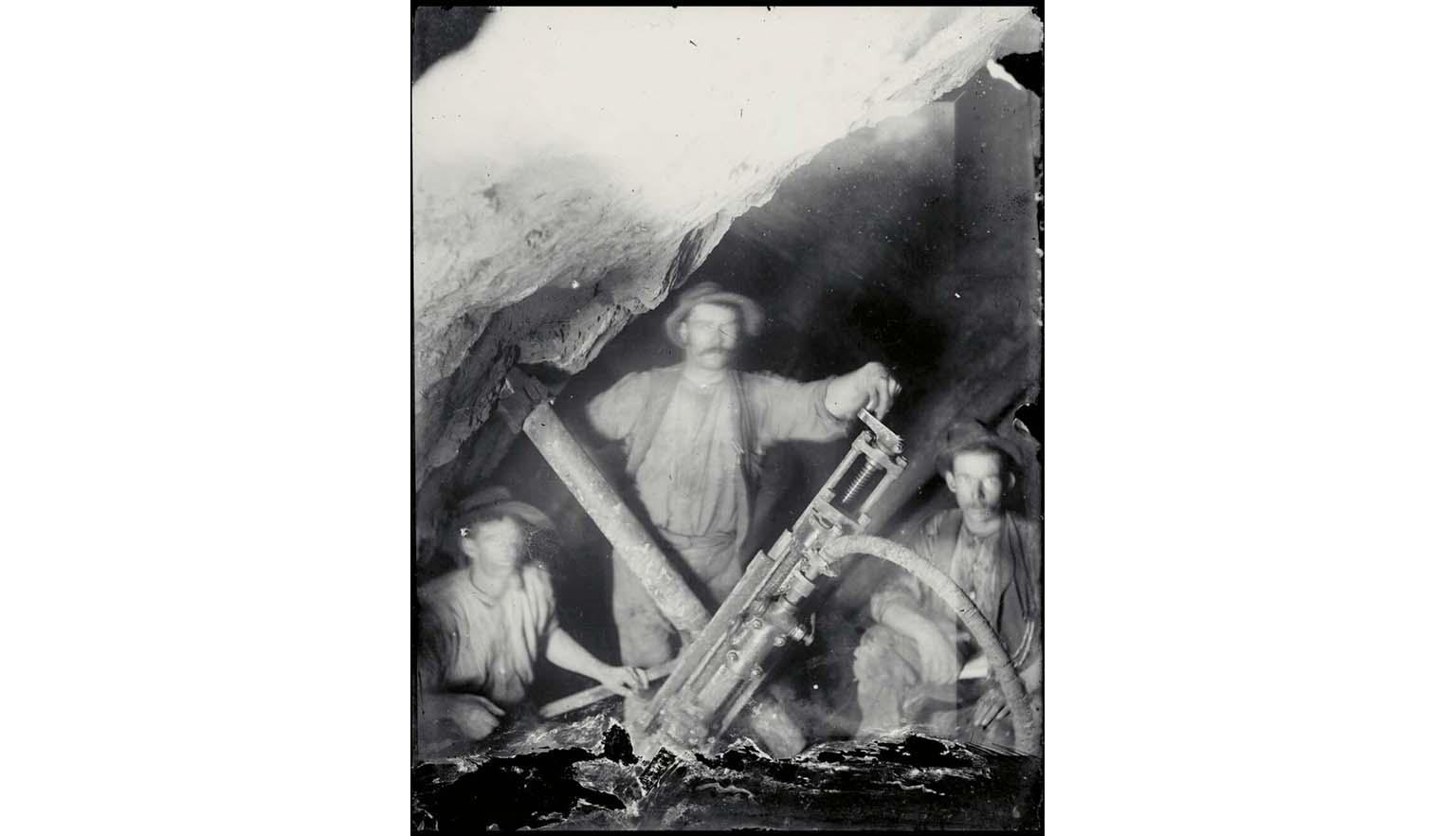

1889: Electric drill

Humans first used simple rotary tools around 35,000 BC. Using a sharp rock spun in the hands, they drilled holes through wood, bone or antlers. The ancient Egyptians used bow drills in carpentry and jewellery making from around 2,500 BC.

Heavy drills were used on the Australian goldfields in the 1800s to tunnel through hard bedrock and into the quartz that held the precious gold. Drills were cranked by hand, waterwheel or windmill until 1889, when Arthur James Arnot of Melbourne patented his design for an electric drill.

With a background in electricity, Arnot designed a large drill that would be able penetrate coal and rock, and was mostly intended for use in the mining industry. His drill was different to the power drills we use today, and much larger. Nonetheless, his drill is considered to be the original prototype which led other inventors to create the smaller, handheld electric drill.

German brothers Wilhelm and Carl Fein invented the first portable drill several years after Arnot came up with his design. The electric drill we see in our toolboxes today was developed in 1900.

Modern Australia: The 20th century

1948: Hills hoist

The Hills hoist transformed backyards across Australia in the years following the Second World War - all because of some lemon trees in a suburban Adelaide garden.

In 1945, Lance Hill and his wife were fed up with half their clothesline being blocked by a lemon tree. They needed more space to hang their clothes. Rather than getting rid of the tree, Hill looked for alternative solutions. Using his home laundry as a workshop, he fashioned an innovative replacement: a rotating clothesline that could be raised or lowered.

Hill sold his first clothesline in 1946. Soon orders became too much for Lance and his brother, who had joined the business, to handle. In 1947, they moved into a larger workshop, bought three trucks and employed staff to help assemble the clotheslines that have come to symbolise Australian suburbia. Hills Industries, as the company is known today, still produce clotheslines, as well as security systems, car parts and garden equipment. In 1994, the company sold its 5-millionth clothesline.

Abraham Valentine Booth, Two women hanging washing on a line, Wagga Wagga Region, New South Wales, ca. 1912, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-151874333

Abraham Valentine Booth, Two women hanging washing on a line, Wagga Wagga Region, New South Wales, ca. 1912, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-151874333

1951: Victa lawnmower

Before the invention of the motorised lawnmower, push mowers were used to cut grass. Many early models were made of heavy wood and cast iron, and were slow and awkward. They had no motor; the user had to push the mower to make the blades turn. It wasn’t until 1948 that an Australian man, Lawrence Hall, came up with the idea of attaching a plough disc to a boat motor so that he could more easily cut his parents’ lawn. It worked but was very heavy and hard to transport.

In 1951, Mervyn Victor Richardson, an engineer from Sydney, took the basic idea of a powered mower and made one that was light and strong. At first, he sold the mowers out of his house, but there were soon lines of people waiting outside to buy one of the machines, which he had nicknamed the ‘Victa’. Within three years, the company was making 3,000 machines a week. In 2011, the world’s biggest lawnmower factory produced its 8-millionth lawnmower.

Learning activities

Activity 1: Choose and rank influential inventions

Work as a class to agree on a definition of ‘influential’. Then ask each student to name an invention they believe changed human history. Record each student’s response.

- Plot the inventions on a shared timeline. You can group similar inventions or arrange them by how influential the class thinks they are.

Activity 2: Predict future technology

As a class, list major technological advances from the last 50 years. Think about how these advances have changed daily life, work or communication. Now ask students to predict what new technologies we might see in:

- 10 years

- 20 years

- 50 years

Discuss how these future technologies might affect our lives.

Activity 3: Imagine life without a key discovery

Ask each student to choose a scientific discovery or invention made in the last 100 years. Then have them imagine life without it.

Some ideas include: Wifi, plastic bank notes, google maps, the flight recorder (aka black box), the pacemaker, latex gloves and the cochlear implant.

- Get students to describe how their daily routines, health, learning or social life might be different.