Medieval manuscripts

About our medieval manuscripts

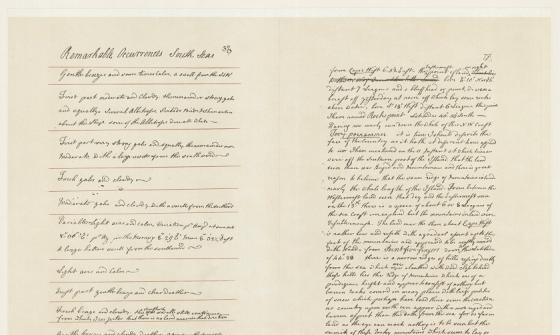

The Library’s medieval manuscripts comprise more than 6000 individual folios in 250 items and 12 bound volumes, dispersed across several collections.

The bulk were acquired from two sources: ten volumes from the library of the 11th Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, and a large group of legal documents and fragments from manuscripts of theological, biblical, musico-liturgical and literary works from Sir Rex Nan Kivell, collected for his Calligraphy Collection.

Explore our medieval collections

- The Clifford Collection, 13th-15th centuries. 10 volumes including books of hours and bibles

- The Nan Kivell Calligraphy Collection, 10th century to mid-19th century. 250 manuscript fragments and legal documents

Discovery video: Early manuscript and rare book treasures

Discovery Video: Early manuscript and rare book treasures

Hello, my name is Susannah Helman. I'm Rare Books and Music Curator at the National Library of Australia. As we begin I acknowledge Australia's first nations peoples as the traditional owners and custodians of this land, I give my respect to the elders past and present and through them to all Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Today I'm talking about some of the Library's earliest books. Everyone knows that libraries have books, the National Library of Australia is no different. We hold millions of them. The Library has a rich rare books collection. It is strongest in Australian books from the late 18th century onwards as you would expect from the National Library of Australia.

Yet the Library also has a great collection of early printed books, particularly those printed in Britain and Europe and it has collections that can tell the early history of the book, particularly in the west, the transition between manuscript books, books that were written by hand to printed books in which words are printed with type and illustrations are also printed, usually through techniques such as woodcuts and copperplate engravings.

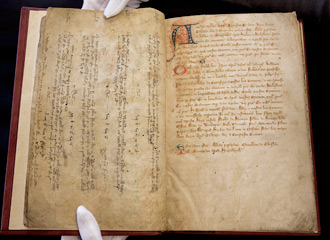

Now I'm going to show you some of the stars of our early collections. We have a small but interesting collection of medieval European manuscripts, both religious and secular, that show, many of them in fragmentary form, the kinds of books produced in Europe in the medieval and early modern period.

Between the 10th and 16th centuries European manuscripts and books evolved and changed. Works of science and religion coexisted. The rise of universities in around 1200 led to an explosion of manuscript works and the growth of a secular book industry beyond the walls of religious houses.

Styles and standards of writing and illumination varied by location, cost and use as well as by the skill of scribe and artist. The invention of movable type in Europe in the mid-15th century had a profound effect on how books were produced and used.

Many medieval manuscripts were broken up and recycled in the bindings of printed books.

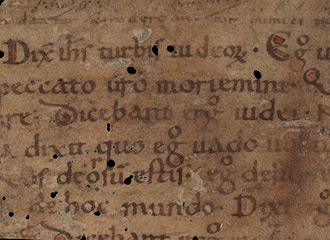

This is the oldest manuscript in the Library's collection, it comes from a Breviary, the service or prayer book used by those in holy orders. Of English origin the writing is Caroline or Carolingian miniscule, a rounded script that flourished during the reign of Charlemagne who lived from around 742 to 814, Holy Roman Emperor.

The script was widely used throughout Europe for centuries and favoured for its legibility. Some of these letters however are formed in ways more characteristic of earlier British or technically Insular manuscripts. You can also see neumes, musical notation.

The parchment's dark colour may have been caused by chemical damage. Most medieval manuscripts were written on prepared animal skin called vellum or parchment. These terms are often used interchangeably today although to be strictly correct parchment refers to sheep and goatskin and vellum to the finer calf skin.

This leaf with its gash sewn up makes its animal origins clear. As the holes made by thread are stretched the sewing was most likely done by the parchment-maker while the skin was supple and still being prepared rather than during any later repair. The thread is still in place. The text is from one of the great works of medieval theology, the sentences by Peter Lombard, Bishop of Paris.

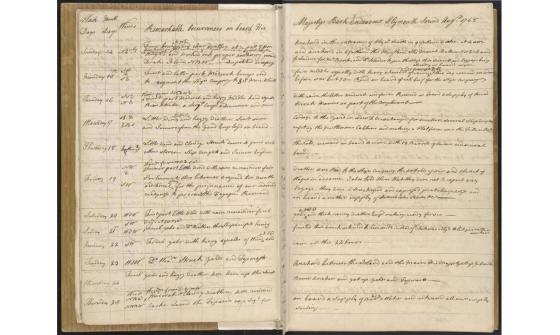

This important cartulary, a compendium of historical and business records, is one of five such volumes to survive from the English Benedictine Abbey at Chertsey in Surrey. Dissolved by King Henry VIII in 1537 Chertsey Abbey was one of over 800 religious houses whose lands and possessions were appropriated by the King after he broke from Rome and established his own Church of England. This volume dates from the Abbey's prime during the rule of Abbot John of Rutherwick, an expert administrator. It is effectively the Abbey's record of its history including copies of documents and charters. In the hands of two or more scribes it records the Abbot's acts and the Abbey's property interests. Some earlier accounts, the only extant examples, were used in the original binding making this cartulary particularly significant.

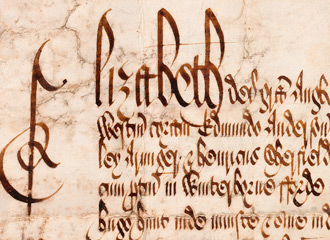

The Library has a substantial collection of early English legal documents. This example shows they were not all boring to look at. It is written on the flesh or smoother side of the parchment. It is a contract called an Indenture or chirograph. Two copies would have been written out, one above the other. Before being cut chirographum, or a variation thereof, meaning autograph was written as a security measure.

This is a book of hours dating from around 1450 and made in the southern Netherlands, probably for the English market. Books of hours were prayer books for private devotion and were very popular in Europe from the 13th century. This example was no doubt made for an English patron, possibly in Bruges or Ghent, then centres of illuminated manuscript production.

Annotations within the volume show that it has been used by English speakers.

It is often considered our most splendid book of hours but it has obviously been well loved before that. It has inscriptions and many of the borders are worn.

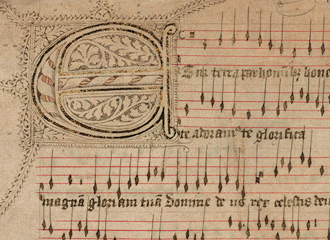

This illumination called an historiated initial as seen within a letter was cut from a large antiphonal a volume used by medieval and Renaissance choirs. Cathedrals and monasteries usually had a set of 12 to 14 antiphonals spanning the church year, each with a small number of illuminations. The musical notation was so large it could be seen from a distance.

This illumination shows the 4th century St Martin of Tours who served as a Roman soldier in Amiens. Beside him is the beggar with whom Martin shared his cloak and who he later dreamed was Jesus. The image appears within a letter O, the first letter of the Magnificat, song of Mary, sung on the Feast of St Martin, the 11th of November which begins "O beatum virum!", "Oh blessed man!"

The Library's oldest printed item dates from 1162. It was printed in China, a Chinese translation of a Sanskrit Buddhist scripture.

Books published before 1501 are called incunabula. That word means swaddling clothes or cradle in Latin. That means that they come from the earliest years of printing.

They are often studied separately from books that appeared afterwards.

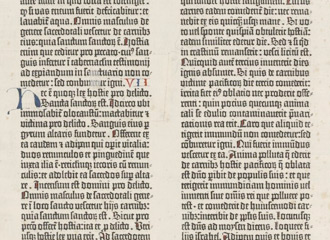

Johannes Gutenberg's Bible, the first major work printed with moveable type, appeared in the mid-1450s. Its printing was a pivotal moment in the history of the book. Also called the 42-line Bible it was the first major book printed with movable metal type in Europe. The type used echoes that of contemporary manuscripts. In its blue and red splitch running titles at the top of each page for the names of the book of the Bible, it resembles those of 13th century Bibles.

About 180 Gutenberg Bibles were printed on both vellum and paper yet only around 48 survive, 23 complete. While the main text is printed the red and blue letters and highlighting were done by hand. Some copies of the Gutenberg Bible were elaborately illuminated after printing.

Our leaf is on the modest end of the scale. This renowned and significant early work on witchcraft, Malleus Maleficarum, the Hammer of Witches, was published widely until the 17th century. It has often been seen retrospectively as a manual for the Inquisition in its quest to rid Europe of witchcraft. The margin notes in this early Latin copy show it has been much used.

The Nuremberg Chronicle is one of the earliest and most ambitious printed books. It is known for its extraordinary woodcuts which reflect new information gained by voyages of discovery and the coexistence of Christian and Ptolemaic thinking at this time. A fusion of Biblical history and geography the book outlines history from the creation to 1493.

This very rare printed book of hours was printed in Paris for an English entrepreneur. It shows how decades after Gutenberg's printed Bible there was still a demand for books of hours and how early printed books emulated earlier manuscript forms. Paris publishers, most of whom worked near Notre Dame Cathedral on the le de la Cit used a combination of woodcut and metal cut prints for the illustrations.

This book tells of the life and suffering of Christ. Its artist, Albrecht Durer, is commonly regarded as the most important artist of the northern Renaissance. His specialty was printmaking, particularly woodcuts and he was ambitious and innovative in his work. Few copies of this popular book survive intact.

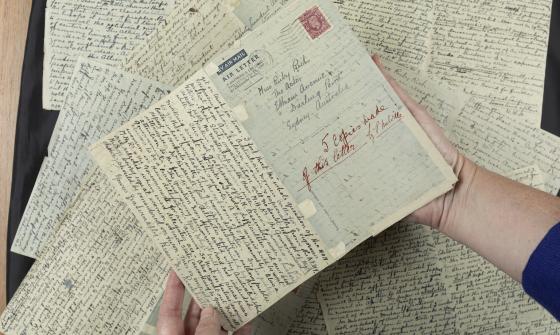

To time travel a century or two I'm going to end with two early works printed in Australia.

The first is this, the earliest surviving work printed in Australia. It was discovered in a collection in Canada and given to the people of Australia by the Government of Canada. It advertises a long evening's entertainment at Sydney's theatre.

A play, Nicholas Rowe's Tragedy of Jane Shaw, a farce and a dance. The performers were convicts and organised the performance themselves. The second is the earliest illustrated book printed in Australia. This is John Lewin's extremely rare Birds of New South Wales from 1813.

To find out more about our collections you can find more information on our website, online catalogue and keep an eye on our social media channels, blogs and events.

We have pages on our website about our medieval manuscripts including digitised images of our holdings, thanks to the generous support of donors to the 2014 Annual Appeal. Alternatively you can get a library card, search our catalogue and call up an item to view in our Reading Room.

We look forward to seeing you in person, online or both. Thank you for watching.

Gems of history

Gems of history

Collection highlights

Medieval and renaissance treasures

Book of Hours

The Commendation of Souls in Book of Hours c. 1450 (Use of Sarum), Southern Netherlands, ink, pigment and gold on parchment, CLIFFORD COLLECTION (MANUSCRIPTS)

Books of Hours, prayer books for private devotion, were very popular in Europe from the thirteenth century.

This example was no doubt made for an English patron, possibly in Bruges or Ghent, then centres of illuminated manuscript production.

This full-page miniature shows the raising of the dead to Heaven, illustrating the text of a sequence of psalms together known as the Commendation of Souls.

Chertsey Cartulary

Chertsey cartulary c. 1313–1345 with earlier flyleaves, Surrey, England, ink and pigment on parchment, CLIFFORD COLLECTION (MANUSCRIPTS)

This important cartulary, a compendium of historical and business records, is one of five to survive from the English Benedictine abbey at Chertsey in Surrey.

The abbey was dissolved by Henry VIII in 1537 but the volume dates from the abbey’s prime under Abbot John of Rutherwick.

It is the abbey’s record of its history, including copies of documents and charters. Some earlier abbey accounts - the only extant examples - were used in the original binding.

Bathsheba

Bathsheba and King David in Book of Hours c. 1400, Northern France, ink, pigment and gold on parchment, CLIFFORD COLLECTION (MANUSCRIPTS)

French Books of Hours often used the biblical story of Bathsheba - wife of King David and mother of Solomon—to accompany a sequence of psalms.

David killed Bathsheba’s husband, Uriah, so he could marry her. Bathsheba is often depicted nude and as a temptress. In this Book of Hours, someone has taken their wrath out on Bathsheba, likely with a wet finger, and dissolved the paint.

Gutenberg

Leaf from the Gutenberg Bible, Book of Leviticus, Mainz: Johannes Gutenberg, c. 1453–1455, ink and pigment on paper, OVERSEAS RARE BOOKS COLLECTION

The printing of the Gutenberg Bible was a pivotal moment in the history of the book. It was the first major book printed with moveable type in Europe.

About 180 Gutenberg Bibles were printed, on both vellum and paper, yet only around 48 survive, 23 complete.

Historiated initial

Historiated initial of St Martin and the beggar between 1450 and 1475, Northern Italy (possibly Savoy), ink, pigment and gold on parchment, REX NAN KIVELL COLLECTION (PICTURES)

This illumination - a historiated initial, a scene within a letter - was cut from a large antiphonal, a volume used by medieval and Renaissance choirs.

It shows the fourth-century St Martin of Tours, who shared his cloak with a beggar.

The image appears within a letter ‘O’.

Oldest manuscript

Fragment of a response from a breviary 10th century, England, ink on parchment, REX NAN KIVELL COLLECTION (MANUSCRIPTS)

Over 1,000 years old, this is the oldest manuscript in the Library’s collection. Of English origin, the writing is Caroline minuscule, a rounded script widely used throughout Europe for centuries and favoured for its legibility.

Some of these letters, however, are formed in ways more characteristic of earlier British manuscripts.

Legal document

Exemplification of a recovery relating to property in Winterborne, Forde, Laverstock and Stratford 30 June 1596, Westminster, England, ink on parchment, wax, REX NAN KIVELL COLLECTION (MANUSCRIPTS)

In sixteenth-century England, legal documents could be very impressive.

Written on parchment, with a wax seal, this deed lays out what was resolved before the Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas. Elizabeth was on the throne at the time.

Choirbook fragment

Fragment of a choirbook, known as ‘H6’, possibly used in King Henry VI’s chapel c. 1430, England, ink and pigment on parchment, REX NAN KIVELL COLLECTION (MANUSCRIPTS)

This is one of a few surviving fragments of a manuscript choirbook believed to have been used in a royal chapel in King Henry VI of England’s reign (1422-1461).

Several other fragments have been found in the bindings of books now held in British libraries.

Nicholas Spierinck, a Cambridge bookbinder of the early sixteenth century, possibly acquired the choirbook, and used it as binding material.

Dürer

ALBRECHT DÜRER (artist, 1471–1528), BENEDICTUS CHELIDONIUS (author, 1480–1521), Little Passion (Passio Christi), Nuremberg: Albrecht Dürer, 1511, woodcut and letterpress, CLIFFORD COLLECTION (OVERSEAS RARE BOOKS)

This book - which tells of the life and suffering of Christ - was printed within a few years of the Rothschild Prayer Book.

Albrecht Dürer is commonly regarded as the most important artist of the Northern Renaissance.

His specialty was printmaking, particularly woodcuts, and he was ambitious and innovative in his work.