Artworks in and around the building

As the concept for the Library's building developed, the chief architect, Walter Bunning (1912-1977), made the suggestions for initial artworks, believing they should reflect the classical style of the architecture.

Most of these works of art were commissioned by Bunning around the time the Library was opened in 1968, and can still be found in the foyer, exterior and grounds of the building.

As the Reading Rooms changed over the years, more artwork was installed in these spaces, displaying some of the unique artwork from the Library's collection, and selected to complement the interior design and intended usage of these rooms.

Discovery video

Discovery Video | Building Art of the National Library of Australia

In all seasons. In Canberra's clear air, the National Library of Australia stands out by day and night.

Its reflection mirrored on the surface of Lake Burley Griffin, bathed in sunshine or softly floodlit.

Its elegant contemporary classical lines proclaim its status as a major landmark in the nation's capital.

While the building has a beauty all on its own, it is the artistic embellishments that elevate it beyond a marble clad mid-century public edifice.

Hello. My name is Grace and I'm a curator at the National Library of Australia.

In this video, we're going to take a look at the National Library's architecture and artworks on display in the public spaces.

Leonard French's jewel like windows, Tom Bass' lintel sculpture. Mathieu Mategot's tapestries. Henry Moore's sculpture, the shimmering works of textile artist Alice Kettle and the decorative panels of Arthur Robb.

I would like to acknowledge Australia's First Nations peoples, the First Australians, as the traditional owners and custodians of the land, and give respect to the elders, past and present and through them to all Australian, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Until the completion of the building in 1968, the Library's collections and staff were spread across several locations in Canberra, housed in over 15 buildings.

It was once said to be the 'worst housed library for its importance in the world'.

It was during this time in the 1950s that a Parliamentary Select Committee inquiry into Canberra's haphazard planning recommended the establishment of a National Capital Development Commission to oversee the city's development and the construction of its monumental buildings.

The construction of the National Library held great importance and even saw Prime Minister Robert Menzies personal interest in its development.

And so the Library's building brief was demanding; as the structure needed to be noble in spirit worthy of both its status as a key cultural institution and of its privileged geographical location.

As the Library was regarded as the first prestigious building in Canberra's Parliamentary Zone, the search for artists and designers of sufficient quality to match the building was crucial.

It was the Sydney architectural firm Bunning and Madden who appointed the Library's architect with Walter Bunning himself, heading as the chief architect.

Drawing inspiration from Bunning's visit to the Parthenon in Greece and American architect Edward Stone, its distinct stripped classical style known as contemporary classical is classical architecture without the use of details or motifs.

Bunning's classical vision meant traditional building materials were used. The exterior of the building is light colored marble with cladding with granite, bronze, slate and copper. The podiums walls are grey trachyte, and the roof is copper.

From the moment of its inception, Walter Bunning understood the significance of the interior furnishings and what the role they played in the building's design. But he believed they should reflect the classical style of the architecture and that a fine building did not require excessive ornamentation.

In keeping with his holistic approach, Bunning made the initial suggestions for six artworks, and he nominated the artists to produce them. The flexible nature of the interior design required to take into account the changing needs of the Library over time also limited the widespread use of fixed artworks.

He suggested that in keeping with its classical style, the artworks should take as themes the classical elements of water, earth and air; ignoring fire. Water would be represented by fountains in the building's forecourt. The external lake-side panels would depict the earth. The foyer stained glass windows would show the planets, while the tapestries would evoke the sun, moon and stars.

Designs for all artworks had to be approved by the Commonwealth Art Advisory Board.

Most of these works of art were commissioned by Bunning around the time the Library opened in 1968 and can still be found in the foyer, exterior and grounds of the building. Today, as visitors enter the National Library of Australia, they pass under the monumental 'Library Lintel Sculpture' by Australian artist Tom Bass. The copper sculpture, which was installed shortly before the building opened in 1968, features imagery related to the role of the Library as a repository of culture and knowledge.

A closer look at this impressive artwork reveals the meaning behind its composition. Bass was approached about the commission in 1966. The building's architect, Walter Bunning, asked him to work with the classical elements water, earth and sky. Bass was aware of the need to make a striking work to symbolise the purpose of great libraries as documented in his papers and those of Bunning.

The design was first developed as a maquette, a small preliminary model, and then created at its full size by Bass with metal fabricator Kevin Goodridge. Shapes of copper were cut to size and given a hammered finish, then welded together and secured to steel frames, weighing in at about three tonnes in total.

The strength and colour variety of the material contribute to the artwork's success. Bass explained how 'through heating and annealing and welding' the colours that emerge are blended and 'the hammered forms and surfaces glow and reflect and are brought out to capture the light'.

In 1968, Bass wrote to the National Librarian, Harold White, outlining his thoughts on the work which he described as being conceived from 'a progression of intuitions and evolving ideas; thoughts of the Library as a living centre of knowledge and the vessel of our cultural residues'. This observation makes clear his intention to design something that expressed the cultural significance of the Library.

The Library Lintel Sculpture measures over 21 meters in length and was made in three parts at Bass's Farm in Minto, New South Wales. Each section features a dominant symbol, a winged sun in the center with an arc on one side and a tree on the other.

The imagery was inspired by ancient Sumerian cylindrical seals, which, as Bass explained elsewhere, were used by the Sumerians as insignia to authenticate their cuneiform writings, and they were rolled across the clay envelope in which the writings were enclosed. He added that the sculpture could be considered as the seal of authentication of the contents of the Library, which it encloses. Upon looking at Bunning's plans for the Library building, Bass was reminded of these seals, partly due to their links with the origins of writing.

Each of the three symbols in the lintel relates to the role of the Library. Bass wrote that, for him, the themes 'are "ultimate or absolute truth" shown as a winged sun...which in this context aims to project the immense power and revelation of inspired truth'. The symbol merges into the next one as 'one of the wings becomes "the tree"... to express the growth of knowledge generated by truth'. Finally, he described the ark as 'the timeless image of conservation', which is 'like a honeycomb heavy with the nectar of our cultural residues'.

As we enter our Foyer, we find the three large iconic tapestries hanging above the entrance.

Conceived to harmonise with Leonard French's stained glass windows, Mathieu Mategot's tapestries are bold in design and make forceful use of colour to anchor the Foyer's expanse of sandy colored travertine marble.

Jean Lurcat was originally commissioned by Bunning to create the tapestries, but he died before completing the designs.

Mathieu Mategot, Professor of Art at the prestigious École des Beaux Arts in Nancy, France, was chosen to be Lurcat's successor.

Born in Hungary and living in France, Mategot initially worked in theater design and also crafted furniture, but became best known for his monumental tapestries.

Mategot was asked to portray the Australian experience and after a visit to the country in 1966 to research his designs, the works were installed in time for the Library's opening in 1968.

Using Australian merino wool, they were woven in Aubusson, France, a celebrated center for tapestry design and weaving.

Each tapestry is over five meters high and three meters wide and they were designed to be best viewed from the Library's mezzanine level.

The first tapestry depicts the radio telescope at Woomera, South Australia, representing the technological times in which the Library was built. Woomera was NASA's first deep space station located outside of the United States. It participated in a number of early important space missions.

The middle tapestry depicts Australian flora and fauna. The two meter parrot represents 'Terra Psittacorum' or 'Land of the Parrots', a name given to the Australian region in early navigational charts.

The third tapestry has a multitude of themes, starting from the top. It shows a blue area symbolising the Great Barrier Reef. The pineapple evokes tropical Australia and the riverboat and the outline of the Sydney Opera House represent urban life. The rams head stands for wool, Australia's major export at the time. With the brown area at the bottom representing the land.

There are many things that make the Library remarkable, including the colored glass windows in the building's Foyer.

They are a testament to the talent and vision of artist Leonard French.

A closer look at the process behind the windows helps us understand why they are mesmerising artworks.

They were commissioned by Bunning and installed in 1967.

There are sixteen windows, each measuring 3.45 metres in height and 1.3 metres in width and composed of four panels.

As art historian Sasha Grishin has shown, French took inspiration from Gustav Holst's 1918 orchestral suite 'The Planets' with the six pairs and four single windows, each featuring a slightly different color palette. Warm shades dominate on the lakeside and cool ones on the other side where the Bookshop is. The language of symbols used, including crosses and mandalas, as well as celestial imagery connects with French's broader work, which predominantly consisted of paintings.

Although referred to as stained glass, the windows were executed in the dalle de verre technique (also known as faceted glass), which was developed in the early 20th century. Whereas stained glass is pieces of glass held together with strips of lead (called lead cames) and decorated with special paints, dalle de verre consists of chunks of faceted glass arranged in mosaic like patterns; thick borders reinforce the intensity of the color.

The glass is chiseled in places to 'prismatise the edges' in order to bring the light through, as French explained.

Having selected the correct colour of glass, French and his assistant cut it to size and then chiseled its edges.

Each 2.5 centimeter thick piece was arranged against the correct panel of the 64 that compose the total scheme and encased in a rubbery substance. Once set, the rubber was cut away except for the front of the glass.

The final stage involved reassembling the glass within a frame. Ciment fondu, also known as aluminous cement, was then poured over. When firm the remaining rubber was removed, leaving a recess at the front of the panel.

Like stained glass , dalle de verre windows modify the amount of light entering the space, but they do so more dramatically.

As French has observed: 'The purpose of these windows is to flood the place with brilliant coloured light'.

It is perhaps for this reason that exhibitions were originally located in the space now occupied by the Library Bookshop and the Bookplate Café.

Situated in the Library, grounds near the front of the building, you will find Henry Moore's 'Two Piece Reclining Figure No.9'.

Regarded as one of Britain's most eminent modern sculptors, Moore was born in Castleford, Yorkshire and studied sculpture at the Leeds School of Art and the Royal College of Art London.

Two Piece Reclining Figure No. 9 is one of nine two-piece sculptures that Moore created starting in 1959, and this one is one of seven casts. The other six went to the United States.

Originally, the sculpture was to be displayed on the Library's front podium. However, it was felt to be inappropriate for this location.

Consequently, the sculpture was placed on the Library's boundary on a plinth designed by Walter Bunning.

Interesting to note that while there is a strong connection of association with the Library, it is in fact owned and maintained by the National Capital Authority.

Often overlooked by visitors to the Library are the seven panels running along the outer lake-side wall of the Main Reading Room.

They were designed by Arthur Robb, a young architect and draftsman with the building designers, Bunning and Madden.

Bunning claimed that the circles, diamonds, crosses and other shapes with their rugged Roman feel were inspired by the decoration on gladiator shields.

The geometric patterns also echo the motifs seen in Leonard French's stained glass windows.

The panels are fabricated from sheet copper and beaten into profile, probably over timber forms.

The artisan was Z.S. Vesely, whose Sydney foundry also executed works for Tom Bass. Vesely's name is inscribed on the centre panel to match the tone of his lintel sculpture.

The panels were specially treated to simulate increased age.

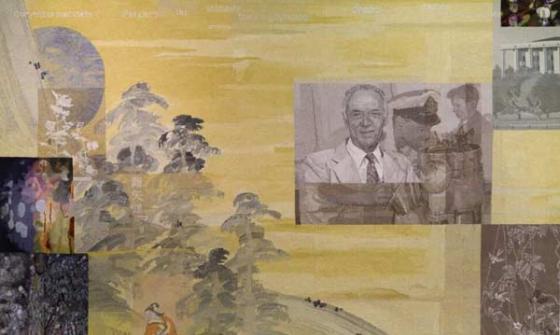

This tapestry was donated by the Myer family through the Tapestry Foundation of Victoria in 2011. It commemorates the life and adventures of American born Australian patron of the arts, Kenneth Baillieu Myer AC DSC.

In 1961, Myer was a founding member of the National Library Council and from 1974 to 1982 was Chair of Council.

At the time of his death, Myer was the greatest collector of Japanese art in Australia. His philanthropy included personal donations and funding to the National Library of Australia, Victorian Art Center, CSIRO and Art Gallery of New South Wales.

With his siblings, he established the Sidney Myer Music Bowl in 1959 in honour of their late father, Sidney Myer.

Melbourne artist John Young, designed the tapestry to represent Myer's many interests and passions, including gum forests, Oriental art and technological enterprises in fields such as optic fiber and modified crops. It also refers to his distinguished career during World War Two and his passion for collection building by Australian cultural institutions.

At the centre left of the tapestry, Kenneth Myer's name is featured in Chinese symbols, which translate as 'rigorous dancing arrow'.

Alice Kettle's four machine-embroidered panels have been displayed in the Main Reading Room since 2001.

The three panels hanging together evoke a populated landscape with the impressionistic imagery referencing the Library's maps collection. The Southern Cross is depicted at the top of the centre and left hand panels, and the red line and text across the foreground is from a map drawn in 1570 by Abraham Ortelius. A fourth panel, hanging at the opposite end of the Reading Room, features a single eucalypt.

Kettle conceived the panels as a commentary on the relationship between readers and libraries and between people and landscapes. British textile artist Alice Kettle estimates she used 5 million stitches in the panels, which took 18 months to create. Many of the fine threads are made from synthetic rayon and cotton.

As Kettle described her inspiration: 'They capture the luminescence of the shifting light and the brilliance of the landscape'.

As the Reading Rooms changed over the years, more artwork was installed in these spaces, displaying some of the unique artwork from the Library's collection and selected to complement the interior design and intended usage of these rooms.

The Main Reading Room showcases artwork that is inspired by Indigenous stories of the Australian landscape.

The Special Collections Reading Room houses art focusing on modern Australian people and places.

Today, the Library stands true to Bunning's architectural and artistic vision.

While the building has been a landmark in Canberra since its construction, its inclusion on the 2018 Commonwealth Heritage List highlights its significant aesthetic and cultural contribution to the nation's capital.

If you want to learn more about the heritage of the Library's building, artwork and design, you can head to the National Library of Australia's website for more information using the links below.

Thank you for watching.

Visit us

Find our opening times, get directions, join a tour, or dine and shop with us.